eBook - ePub

Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience

Richard Carr, Noah Hass-Cohen

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience

Richard Carr, Noah Hass-Cohen

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience offers an authoritative introductory account of recent developments in clinical neuroscience and its impact on art therapy theory and practice.

Contributors explore the complex relationship between art and creativity and neurological functions such as those that occur during stress response, immune functioning, child developmental phases, gender difference, the processing of imagery, attachment, and trauma. It deciphers neuroscientific language and theory and contributes innovative concrete applications and interventions useful in art therapy.

This book is essential reading for art therapists, expressive arts therapists, counselors, mental health practitioners, and students.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience par Richard Carr, Noah Hass-Cohen en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Psychology et History & Theory in Psychology. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

PsychologySous-sujet

History & Theory in PsychologyPart 1

The Framework

1

Partnering of Art Therapy

and Clinical Neuroscience

and Clinical Neuroscience

Noah Hass-Cohen

Art therapy is poised to take advantage of the abundance of information from clinical neuroscience research. We can draw from clinical neuroscience to describe and enhance the therapeutic advantages of arts in action and further illuminate the unique contributions of art therapy to well-being and health.

Clinical neuroscience is the application of the science of neurobiology to human psychology. Human and animal empirical research is revealing the dynamic interplay of the nervous system, particularly the brain, with a person’s environment. Neuroimaging studies allow clinical neuroscientists to hypothesize about structural, functional and environmental correlations that connect observable human activity with measurable brain activity. The connections between the nervous system, the endocrine system and the immune system all shed light on the intrapersonal expressions of the relational self.

In art therapy, the artwork is a concrete representation of such mind-body connectivity, which contributes to internal feelings of mastery and control (Camic 1999; Malchiodi 1998; Naparstek 1994). In the art therapist’s presence, the artwork is an expression of how the self organizes internally as well as in relationship with others. It is a visual reiteration of the interplay between the person and their environment. An understanding and appreciation of mind-body connectivity and interpersonal neurobiology (Siegel 2006) can also facilitate a dialogue about potential contributions of clinical neuroscience to art therapy (Lusebrink 2004). Art therapy practices, research, and theory-building can be updated to suggest a new framework of art therapy relational neurobiology principles (ATR-N) (Hass-Cohen 2008; Figure 1.1).

Mind-body connectivity

The interplay of experiences, emotions, behavior and physical health characterize the study of mind-body connections (Achterberg et al. 1994; Cousins 1979). Mind-body approaches link nervous, endocrine and immune systems with physiological and psychological changes. Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) is the discipline that studies these complex, chemical, bodily connections. Understanding the neurobiological connections between the mind and body furthers therapeutic utility rendering the dualistic separation of mind and body a futile Cartesian endeavor (Damasio 1994).

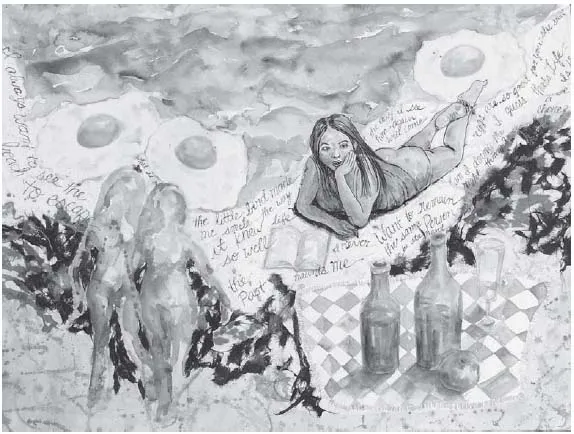

Figure 1.1 How Can Participation in Art Therapy Arouse Positive Feelings, Help Therapists and Clients Understand Complex Material, and Contribute to the Understanding of Self in the World? By Elizabeth Park.

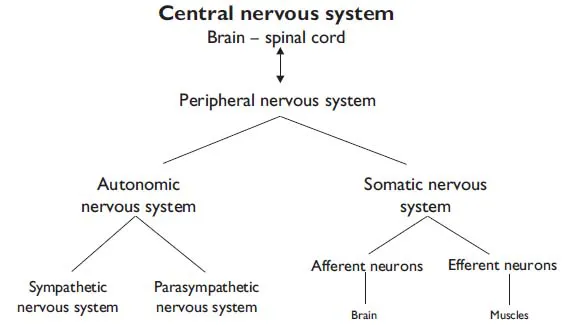

Mind-body connectivity manifests in the nervous system’s organization. The central nervous system consists of the brain and the spinal cord, which innervates the body organs and their extremities through the peripheral nervous system. The peripheral nervous system produces involuntary and voluntary responses to environment. It has two branches: the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary responses to stimuli, maintains normal functions, and restores homeostasis; and the somatic nervous system, which conveys sensory information to the central nervous system and controls voluntary muscular or motor actions (Carlson 2004). Information is received (afferent) and sent (efferent), allowing physiological and psychological changes to unfold. The autonomic nervous system further divides into the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) nervous systems. The SNS’s functioning helps a person quickly adapt to relational and environmental situations. The SNS enhances everyday functioning. Governed by the brain, the sympathetic function propels us into action, such as running away from an environmental danger or struggling with the impulse to avoid a psychosocial conflict. The flight or fight response is associated with SNS activation. In contrast the parasympathetic returns a person to more relaxed, ordinary functioning. If we are able to resolve a stressful problem successfully, the parasympathetic nervous system re-establishes a balance that allows the sympathetic to diminish its flight or fight response. In response to daily circumstances, the SNS and PNS functions complement each other and mildly shift a person between mild variations of excitation and relaxation states (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system includes the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system divides into the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. The autonomic nervous system contains the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) nervous systems. The sympathetic system is excitatory and the “para” (meaning over) sympathetic attempts to restore normal function by counterbalancing the sympathetic. The somatic/sensory nervous system responds to incoming afferent sensory messages and carries efferent messages to the major voluntary muscle groups.

Initially, the strain of a novel demand, such as art-making, can be experienced as a SNS excitement and emotionally anticipated. However, if the task is not mastered and the client’s sense of control is challenged, the SNS stress response might increase. For example, Mary, a 60-year-old client struggling with leukemia and loneliness, reported that she was initially excited about the fine art class recommended by her church counselor. She hoped to gain some support as well as express some of what she was going through. Mary reported that she was discouraged by her lack of art skills, and she left the course after a couple of classes. She did not feel safe in the judgmental fine arts environment. Recognizing her need to create art in a non-threatening and supportive environment, she successfully sought out an art therapist.

At times, psychosocial stressors may not be able to be resolved by leaving the situation or finding new ways of coping, which contributes to a sense of fear and loss of safety (Sapolsky 1998) often expressed by clients. In order to regain a measure of safety and control, art therapists encourage clients to practice taking action in session. Actions such as drawing or sculpting in the face of difficult issues can express the voluntary function of the somatic nervous system and provide clients with the opportunity to participate in pleasurable kinesthetic experiences. Doing so can bring the somatic nervous system’s afferent and efferent nerves into play. Afferent nerves carry incoming sensory information from touching the art materials (soft or sharp, warm or cold), which may elicit emotional reactions such as pleasure, discomfort or distaste. At the same time, efferent nerves cause the necessary muscle contraction needed for drawing, painting and sculpting. Art therapy activities, grounded in affective-sensory experiences, assist in keeping clients in touch with their therapeutic surroundings and can also provide relief through the expression of emotions and the kinesthetic and voluntary actions required to make and complete the art. For example, upon touching the velvety wet clay, a female client became quiet and quickly wiped her hands. She reported recoiling from the cold quality of the clay. Another client reported that the smell of the brown clay reminded her of fond childhood memories creating mud-pies. Such art therapy experiences may help provide a sense of control and mastery, which is mediated by sympathetic-parasympathetic balance (Hass-Cohen 2003, 2007).

An example of mind-body connectivity is the social function of the vagal nerve (the tenth cranial nerve), which has connections to the brain as well as to the chest and abdominal areas. “Gut feelings” can be partially attributed to the vagal nerve’s connections with, and influences on, the digestive system (Carlson 2004). The vagus is also implicated in social engagement functions (Porges 2001) such as described below.

Vagus function was associated with death from the “Voodoo Curse.” Walter Cannon described this freeze response in 1929, and was first to show the connectivity of physical and emotional/psychological stressors (Sapolsky 1998). Cannon hypothesized that the tribesmen’s belief in the witch doctor’s curse caused a prolonged stress response that could sometimes result in death. Believing that the shaman has supernatural healing powers that can give life or take life away creates a complicated cascade of mind-body reactions. Situations appraised as unsafe do not support proactive social interactions and can result in stress, isolation, mobilization and in immobilization (Porges 2001; Kravits 2008).

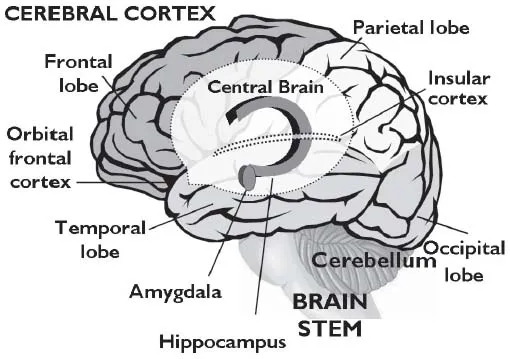

It is important to share with art therapy clients how a person’s response to stress may be affected by how he/she perceives, emotes and thinks about the situation (Barlow 2001) . Thoughts are governed by the functioning of the cerebral cortex, the top part of the brain. Also known as the newest brain, the neocortex covers the limbic system structures located in the central brain and most of the brainstem. Responsible for sophisticated social cognitions, the cortex is considered the seat of thought, emotional appraisal, and voluntary movement. The cortex has two hemispheres, right and left; each side is divided into five lobes (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Cortex, central brain and brainstem. The brainstem and the cerebellum are important for motor reactions and basic body processes. The limbic system within the center brain regions is responsible for social emotional processing. The amygdala triggers the fear response and the hippocampus holds emotional experiences in memory. The cortex is responsible for sophisticated social cognitive functions. It includes the occipital lobe, the parietal lobe, the temporal lobe, the frontal lobe, the orbital frontal cortex, and the insular cortex (located within the sulcus that separates the temporal lobe and inferior parietal cortex. The insula conveys bodily states to the cortex. The orbital frontal cortex is an area above the eyes and behind the forehead (also see Figure 1.7).

The cortex is responsible for linking information from the body, the brainstem and the limbic system. The frontal lobes integrate visual data from the occipital lobes and temporal lobes, along with a sense of space and navigation from the parietal lobes. The temporal lobes are involved with auditory and visual processing. They associate visual social information, such as faces, with meaning and assess it for familiarity. Connections between the temporal lobes and the limbic system allow emotion, recognition and memory to influence the meaning of visual information. The right temporal lobe is associated with nonverbal response-oriented activities.

Chronic stress experiences shift the person away from the integrated feelings and thoughts associated with the function of the frontal lobes towards a limbic-based survival reaction (Henry and Wang 1999). This survival shift stimulates hormonal and neurotransmitter responses that can over time diminish immune system functioning. The limbic system is sensitive to the kind of interpersonal threats demonstrated by the Voodoo death reports. When an immediate threat is not resolved, long-term stress may occur. PNI studies indicate that, to survive, central brain regions signal the endocrine and the immune system to slow down and alter everyday functions. As a result, the effects of chronic stress can be devastating not only to well-being and health but also to memory and cognitive functions (Bremner 2006; Sapolsky 1998).

Art therapy is recognized as an intervention that facilitates the expression of mind-body connectivity through the remediation of acute and chronic stress (Achterberg et al. 1994; Hass-Cohen 2003; Kaplan 2000; Lusebrink 2004). Mind-body-based interventions are also characteristic of health psychology, medical arts, sports psychology and shamanic practices. Treatment interventions in the later modalities include biofeedback, EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), relaxation techniques, sensory-motor sequencing, mindfulness meditation, imagery/guided imagery, hypnosis, rituals, myths and prayer. Most mind-body approaches are intrapersonally oriented. They focus on the remediation of stress and restoring a sympathetic-parasympathetic balance by teaching clients experiential practices. Art therapy differs in that it includes expressive and relational foci. At the same time that art therapists assist clients in reducing the effects of stressors, they also encourage self-expression and promote a sense of intra/interpersonal connectivity through the therapeutic relationship. The advantages are that clients gain more support for generalizing in the outside world what they have experienced in session.

Establishing connectivity: development and learning

The earliest therapeutic relationship between the primary caregiver and infant directly shapes the infant’s emotional brain. From birth, the subcortical regions of the central brain, responsible for emotional processing, are actively making neural connections. Consequently, the infant/caregiver affective relationship has a large impact on neural networks’ connectivity thus shaping brain development and maturation (Diamond and Hopson 1998; Perry 2001; Schore 2001).

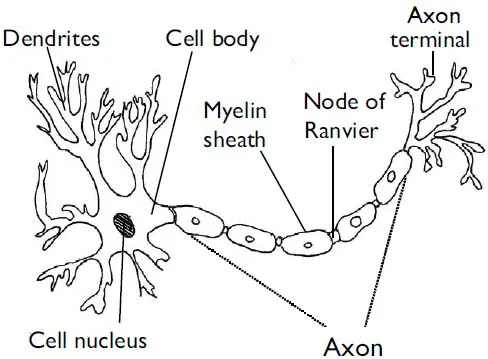

The basic building blocks of relational connectivity are neurons, which are electrically excitable cells. The basic structure of a neuron includes the cell body and nucleus, axon, axon terminals and dendrites. Some neurons are covered by myelin sheathing which facilitates faster communication (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 The neuron image shows the basic neuron structure: dendrites, cell body, cell nucleus, axon, Node of Ranvier, axon terminal and myelin sheath (Nodes of Ranvier are not myelinated).

Shaped like tree branches, dendrites communicate messages from other neurons to the cell body of their neuron. Once a threshold of activation occurs, the neuron activates and fires. Firing causes the cell body to send a single impulse along the axon, a long nerve bundle, to axon terminals. This signal has the potential to activate subsequent neurons. The impulse causes the release of chemical messengers into the space between neurons. Chemical messengers called neurotransmitters negotiate synapses or spaces between the axon terminal of the sending neuron and the dendrites of the receiving neuron. Neurotransmitters stimulate dendrites to convey...