![]()

CHAPTER 1

An Era of Tenuous Majorities

The United States is one of a minority of world democracies that elect their chief executives independently of the legislature. The United States is even more unusual in having two equally powerful chambers of the legislature, separately elected for different terms of office. Moreover, as British analyst Anthony King notes, the two-year term of members of the US House of Representatives is the shortest among world democracies, where terms of four to five years are common.1 Putting all this together, a US national election every two years can generate any one of eight patterns of institutional control of the presidency, House, and Senate (D=Democratic, R=Republican):

1. RRR

2. RDR

3. RRD

4. RDD

5. DDD

6. DRD

7. DDR

8. DRR

The 2004 elections generated pattern 1, unified Republican control under President George W. Bush, but the Democrats captured both houses of Congress two years later, moving the country to pattern 4. The 2008 elections generated pattern 5, unified Democratic control under President Barack Obama, but the Republicans took back the House in 2010, moving the country to pattern 6, and the Senate in 2014, moving the country to pattern 8. Donald Trump’s election in 2016 completed the circle, moving the country back to pattern 1.

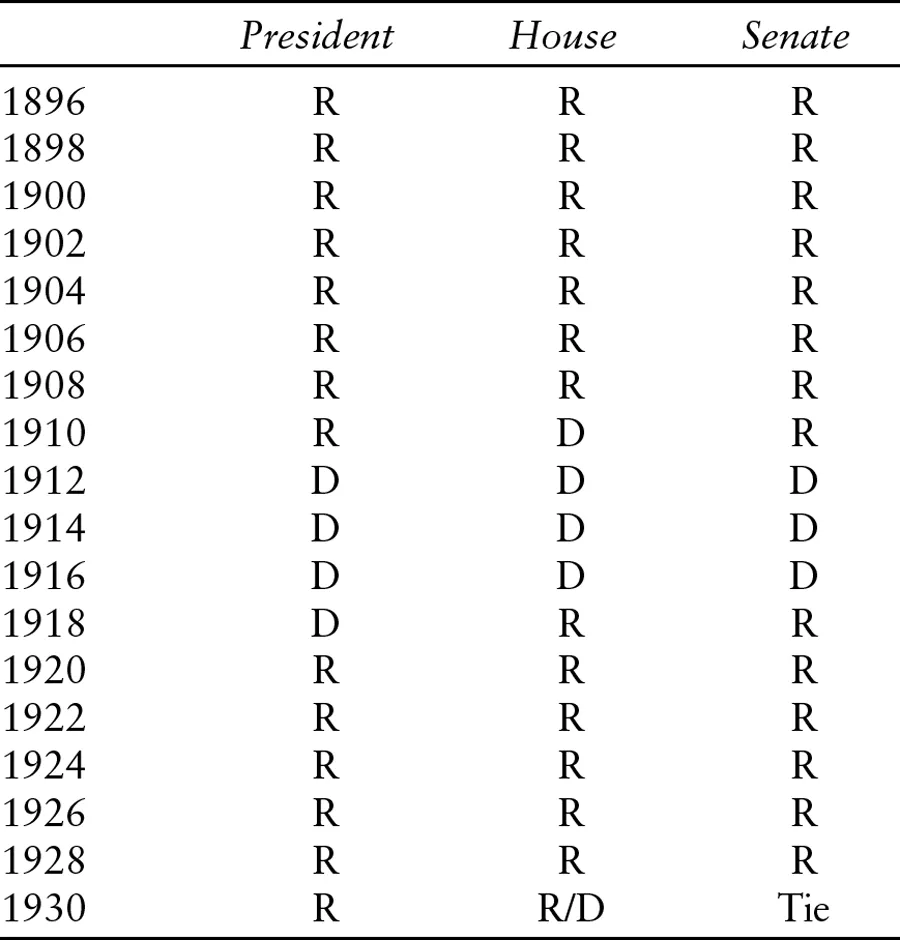

Although an election can produce any of these eight patterns of party control, elections are not independent events like coin tosses; rather, they reflect underlying cleavages that tend to persist over time. Thus, elections in any historical period tend to produce only a few patterns of control. Consider the period known to political historians as the Third Party System. After the devastating depression of the mid-1890s, the Republicans captured the presidency and both chambers of Congress in 1896: see pattern 1, RRR. They retained full control through the next six elections, fourteen consecutive years in all. A split between progressive and conservative factions of the Republican Party enabled the Democrats to capture the House of Representatives in the 1910 midterm elections and to elect Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912 and reelect him in 1916. But the Republicans regained unified control in 1920 and maintained it for the next four elections. As table 1.1 summarizes, the Republicans enjoyed full control of the federal government for twenty-four of the thirty-four years between the 1896 and 1930 elections; the seventeen elections held during that period produced only four patterns of institutional control.

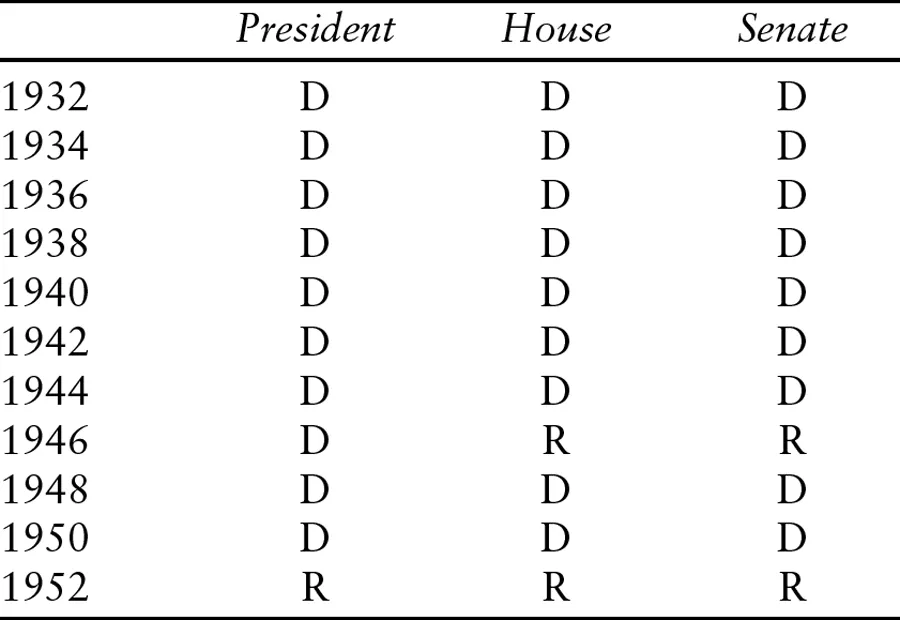

Following the stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, the Republicans lost the House in the elections of 1930 and then all three elective institutions in 1932.2 Like the McKinley Republicans, the New Deal Democrats enjoyed full control for fourteen consecutive years, until they lost Congress in the election of 1946. But they recaptured Congress two years later when Harry Truman was elected in his own right and they held it until 1952. As table 1.2 summarizes, the Democrats controlled all three elective branches for eighteen of the twenty years between the 1932 and 1952 elections; nine out of ten elections produced the same pattern of institutional control.

TABLE 1.1. An Era of Republican Majorities

TABLE 1.2. An Era of Democratic Majorities

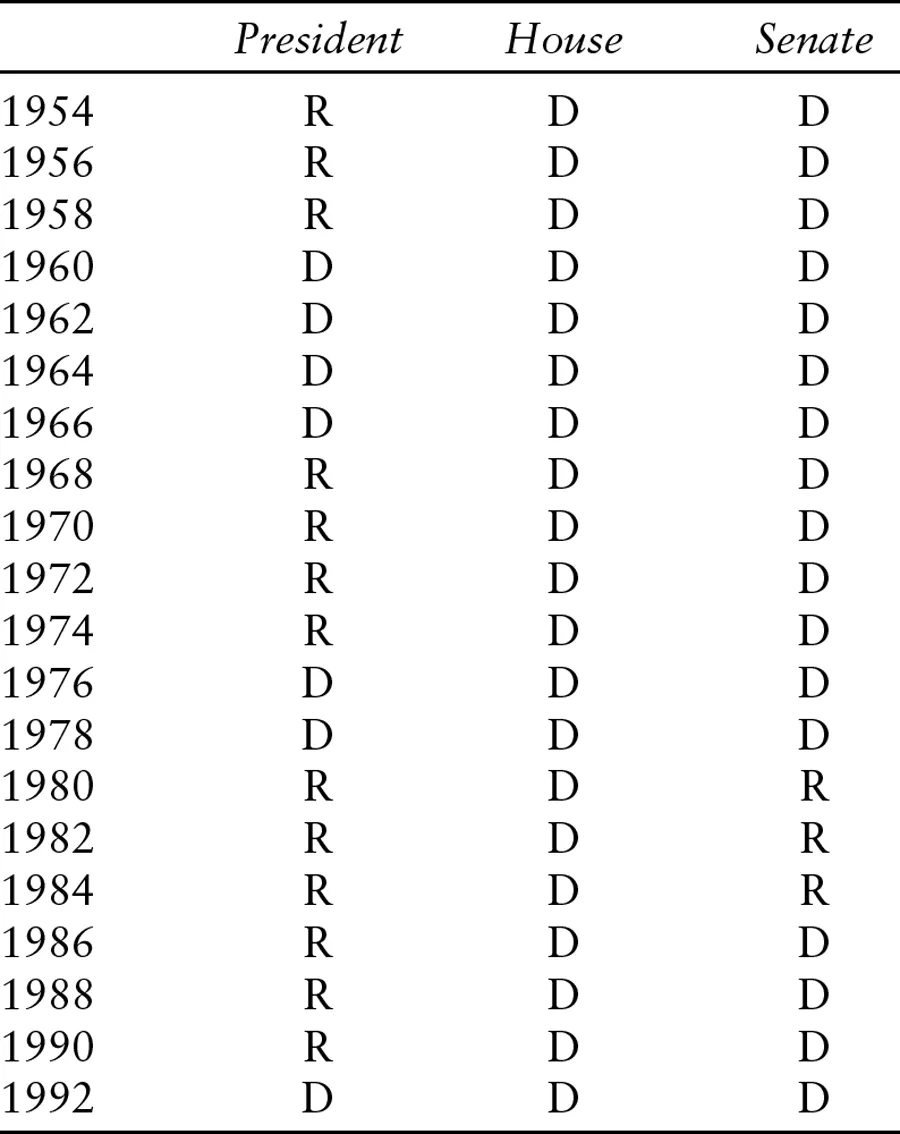

The Republicans under Dwight Eisenhower captured all three branches in 1952 but lost Congress to the Democrats in 1954. So began an era of divided government.3 Although losing control of Congress in the off-year elections was nothing new historically, the 1956 election that followed was. For the first time in American history, the popular vote winner in a two-way presidential race failed to carry the House; only in 1880 had such a winner failed to carry the Senate.4 An interlude of unified Democratic control occurred from 1960 until 1968,5 but the 1968 election marked a resumption of the pattern first observed in the 1950s, when split control of the presidency and Congress became the norm. As table 1.3 summarizes, between 1954 and 1992 thirteen of twenty elections resulted in split control of the presidency and at least one chamber of Congress; after 1968, only four years of unified control during the Carter presidency interrupted what otherwise would have been a twenty-four-year pattern of divided party control under a Republican president. Significantly, however, while government control usually was split during this forty-year period, institutional control remained relatively stable. The Democrats controlled the House throughout the period and the Senate for all but six years. Meanwhile, the Republicans won the presidency seven times in ten tries, including three by landslides, with only a narrow victory by Jimmy Carter in 1976 interrupting what might well have been a string of six consecutive Republican victories.6 Nineteen elections produced only three different patterns of institutional control.

TABLE 1.3. An Era of Different Institutional Majorities

As a consequence, even during this long period of divided government there still was a large degree of predictability. With Republicans generally in control of the executive branch, tax increases were unlikely; with Democrats in control of Congress, spending cuts were unlikely.7 This was bad news for the budget, but the parameters within which deals would be struck were generally understood.

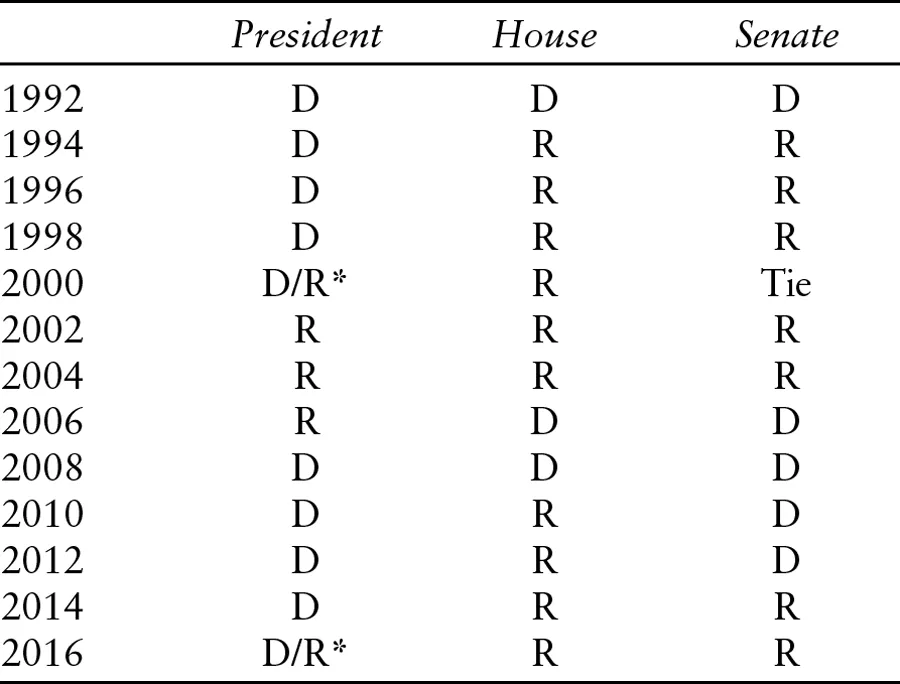

Bad news for the budget was good news for H. Ross Perot, who made budget deficits an issue in the 1992 election. Although it is doubtful that Perot cost George H. W. Bush the election, he probably didn’t help.8 The reestablishment of unified Democratic control under Bill Clinton began a two-decade-long (and counting) period of electoral outcomes that defy generalizations like those describing the three previous eras. Juxtaposed against the relatively stable institutional majorities that characterized the three previous eras, since 1992 the country has experienced an era of unstable institutional majorities. The Democrats have held the presidency for sixteen of the twenty-four years; but neither party has held the office longer than eight years, the popular vote margins have been relatively narrow, and twice the winner of the popular vote lost the electoral vote, an event that had not happened since 1888. Even the reelected presidents (Bush in 2004 and Obama in 2012) have won by relatively narrow margins. Republicans have had an advantage in the House since their 1994 takeover, but the Democrats won majorities twice. Control of the Senate has been almost evenly split. In contrast to the relative stability of institutional control in the three previous eras, the most recent twelve elections have generated six different patterns of control (see table 1.4).

TABLE 1.4. An Era of Unstable Majorities

*Popular vote winner lost the electoral vote

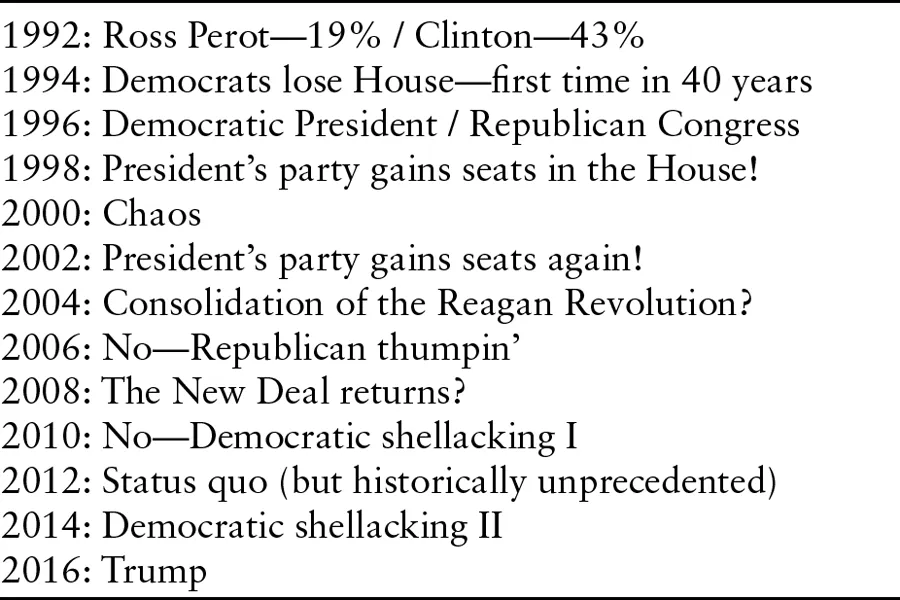

TABLE 1.5. An Era of Instability and Pattern-Breaking

Let us take a closer look at this recent electoral history. Table 1.5 lists the unusual developments that have occurred since 1992. The current era began with the 1992 election itself, of course, when Perot won almost 19 percent of the popular vote, the largest vote for a third place finisher since Theodore Roosevelt split the Republican Party in 1912. Similarly, Bill Clinton became president with 43 percent of the vote, the smallest popular vote percentage for a winner since Wilson’s election in 1912. Then in 1994 the Republicans captured Congress for the first time in forty years, beginning a six-year period of divided government with a Democratic president and a Republican Congress—a reversal of the previous pattern of divided government that blew up a number of political science theories that attempted to explain why Americans supposedly liked Republican presidents and Democratic Congresses.9 After a failed Republican attempt to impeach President Clinton, the Democrats gained House seats in 1998, violating perhaps the hoariest of all generalizations about American politics: that the party of the president loses seats in midterm elections.10 The bitterly contested 2000 elections followed, with a tie in the Senate and the loser of the popular vote elevated to the presidency via the Supreme Court. In 2002, the party of the president again gained seats in a midterm election.

For a brief period, the 2004 elections appeared to put an end to this electorally turbulent decade. After the elections, Republicans of our acquaintance were dancing in the streets (figuratively, at least). Although George W. Bush did not win by a landslide, in capturing the Senate and the House as well as retaining the presidency the Republicans won full control of the national government for the first time since the election of Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, a half century earlier.11 Even in the landslide reelections of Richard Nixon in 1972 and Ronald Reagan in 1984, Republicans had not been able to capture both chambers of Congress.12 In the afterglow of the elections, many Republicans hoped (and some Democrats feared) that Karl Rove had achieved his professed goal of building a generation-long Republican majority, much as Mark Hanna had done for the McKinley Republicans in the 1890s.13

Such hopes and fears proved unfounded, however, as a natural disaster (Hurricane Katrina), a series of political missteps,14 and the weight of an unpopular war in Iraq took their toll on the president’s public standing. In the 2006 elections, which President Bush characterized as a “thumpin’” for his party, the Democrats took back the House and the Senate and netted more than three hundred state legislative seats. Republican fortunes continued to deteriorate in the remaining two years of President Bush’s term. Following an economic collapse in 2008, the Democrats won the presidency to restore the unified control they had lost in 2000. In the short span of four years, party fortunes had completely reversed.

Now it was the Democrats’ turn. Six months after the 2008 elections, Democratic politico James Carville published 40 More Years: How the Democrats Will Rule the Next Generation.15 By no means was Carville alone in his triumphalism. After the elections, pundits and even some political scientists speculated that the 2008 presidential outcome was “transformative” in the sense that it represented an electoral realignment similar to that of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s.16 Again, such hopes and fears proved unfounded, as the (politically) misplaced priorities of the new administration led to a massive repudiation in the 2010 midterm elections, which President Oba...