eBook - ePub

Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation

Richard L. Doty

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation

Richard L. Doty

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The largest collection of basic, clinical, and applied knowledge on the chemical senses ever compiled in one volume, the third edition of Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation encompass recent developments in all fields of chemosensory science, particularly the most recent advances in neurobiology, neuroscience, molecular biology, and modern functional imaging techniques. Divided into five main sections, the text covers the senses of smell and taste as well as sensory integration, industrial applications, and other chemosensory systems. This is essential reading for clinicians and academic researchers interested in basic and applied chemosensory perception.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation par Richard L. Doty en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Biological Sciences et Neuroscience. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part 1

General Introduction

Chapter 1

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Richard L. Doty

1.1 Introduction

All environmental nutrients and airborne chemicals required for life enter our bodies by the nose and mouth. The senses of taste and smell monitor the intake of such materials, not only warning us of environmental hazards, but determining, in large part, the flavor of our foods and beverages, largely fulfilling our need for nutrients. These senses are very acute; for example, the human olfactory system can distinguish among thousands of airborne chemicals, often at concentrations below the detection limits of the most sophisticated analytical instruments (Takagi, 1989). Furthermore, these senses are the most ubiquitous in the animal kingdom, being present in one form or another in nearly all air-, water-, and land-dwelling creatures. Even bacteria and protozoa have specialized mechanisms for sensing environmental chemicals – mechanisms whose understanding may be of considerable value in explaining their modes of infection and reproduction (Jennings, 1906; Russo and Koshland, 1983; van Houten, 2000).

While the scientific study of the chemical senses is of relatively recent vintage, the important role of these senses in the everyday life of humans undoubtedly extends far into prehistoric times. For example, some spices and condiments, including salt and pepper, likely date back to the beginnings of rudimentary cooking, and a number of their benefits presumably were noted soon after the discovery of fire. The release of odors from plant products by combustion was likely an early observation, the memory of which is preserved in the modern word perfume, which is derived from the Latin per meaning “through” and fumus meaning “smoke.” Fire, with its dangerous and magical connotations, must have become associated early on with religious activities, and pleasant-smelling smoke was likely sent into the heavens in rituals designed to please or appease the gods, as documented in later civilizations, such as the early Hebrews. Importantly, food and drink became linked to numerous social and religious events, including those that celebrated birth, the attainment of adulthood, graduation to the status of hunter or warrior, and the passing of a soul to a better life.

In this chapter I provide a brief historical overview of the important role that tastes and odors have played in the lives of human beings throughout millennia and key observations from the last four centuries that have helped to form the context of modern chemosensory research. Recent developments, which are described in detail in other contributions to the Handbook, are briefly mentioned to whet the reader's appetite for what is to follow. Although an attempt has been made to identify, rather specifically, major milestones in chemosensory science since the Renaissance, some important ones have undoubtedly been left out, and it is not possible to mention, much less discuss, even a small fraction of the many studies of this period that have contributed to our current fund of knowledge. Hopefully the material that is presented provides some insight into the basis for the present Zeitgeist. The interested reader is referred elsewhere for additional perspectives on the history of chemosensory science (e.g., Bartoshuk, 1978, 1988; Beauchamp, 2009; Beidler, 1971a, b; Boring, 1942; Cain, 1978; Cloquet, 1821; Corbin, 1986; Doty, 1976; Douek, 1974; Farb and Armelagos, 1980; Farbman, 1992; Frank, 2000; Garrett, 1998; Gloor, 1997; Harper et al., 1968; Harrington and Rosario, 1992; Jenner, 2011; Johnston et al., 1970; Jones and Jones, 1953; Luciani, 1917; McBurney and Gent, 1979; McCartney, 1968; Miller, 1988; Moulton and Beidler, 1967; Moulton et al., 1975; Mykytowycz, 1986; Nagel, 1905; Ottoson, 1963; Pangborn and Trabue, 1967; Parker, 1922; Pfaff, 1985; Piesse, 1879; Schiller, 1997; Simon and Nicolelis, 2002; Smith et al., 2000; Takagi, 1989; Temussi, 2006; Vintschgau, 1880; Wright, 1914; von Skramlik, 1926; Zippel, 1993).

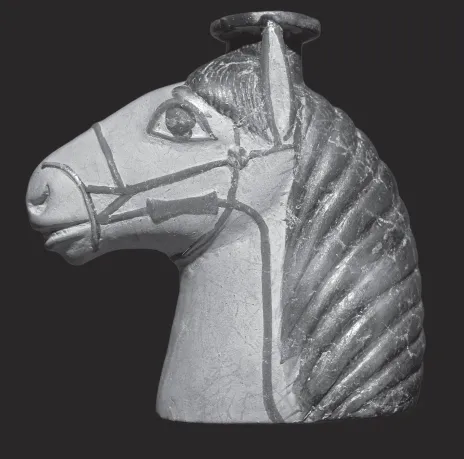

1.2 A Brief History of Perfume and Spice Use

The relatively rich history of a number of ancient civilizations, particularly those of Egypt, Greece, Persia, and the Roman Empire, provides us with examples of how perfumes and spices have been intricately woven into the fabric of various societies. Thousands of years before Christ, fragrant oils were widely used throughout the Middle East to provide skin care and protection from the hot and dry environment, and at least as early as 2000 BCE, spices and fragrances were added to wine, as documented by an inscription on a cuneiform text known as the Enuma elish (Heidel, 1949). During the greater part of the 7th to 5th Centuries BCE, Rhodian potters developed vast quantities of perfume bottles in the form of animals, birds, and human heads and busts that were shipped throughout the mediterranian area (Figure 1.1). In Egypt, incense and fragrant substances played a key role in religious rites and ceremonies, including elaborate burial customs, and whole sections of towns were inhabited by men whose sole profession was to embalm the deceased. As revealed in the general body of religious texts collectively termed the “Book of the Dead” (a number of which predate 3000 BCE; Budge, 1960), the Egyptians performed funeral ceremonies at which prayers and recitations of formulae (including ritualistic repeated burning of various types of incense) were made, and where the sharing of meat and drink offerings by the attendees occurred. Such acts were believed to endow the departed with the power to resist corruption from the darkness and from evil spirits that could prevent passage into the next life, as well as to seal the mystic union of the friends and loved ones with the dead and with the chosen god of the deceased. The prayers of the priests were believed to be carried via incense into heaven and to the ears of Osiris and other gods who presided over the worlds of the dead (Budge, 1960).

Figure 1.1 Example of a horse head perfume bottle manufactured in Rhodes circa 580 BCE. © Heritage Images (Image ID: 2-605-015).

As noted in detail by Piesse (1879), the ancient Greeks and Romans used perfumes extensively, keeping their clothes in scented chests and incorporating scent bags to add fragrance to the air. Indeed, a different scent was often applied to each part of the body; mint was preferred for the arms; palm oil for the face and breasts; marjoram extract for the hair and eyebrows; and essence of ivy for the knees and neck. At their feasts, Greek and Roman aristocrats adorned themselves with flowers and scented waxes and added the fragrance of violets, roses, and other flowers to their wines. As would be expected, perfume shops were abundant in these societies, serving as meeting places for persons of all walks of life (Morfit, 1847). In Grecian mythology, the invention of perfumes was ascribed to the Immortals. Men learned of them from the indiscretion of Aeone, one of the nymphs of Venus; Helen of Troy acquired her beauty from a secret perfume, whose formula was revealed by Venus. Homer (8th century BCE) reports that whenever the Olympian gods honored mortals by visiting them, an ambrosial odor was left, evidence of their divine nature (Piesse, 1879). Interestingly, bad odors were a key element of a number of myths, including that of Jason and the Argonauts (Burket, 1970). As a result of having been smitten with the wrath of Aphrodite, the women of Lemnos developed a foul odor, which drove their husbands to seek refuge in the arms of Thracian slave girls. The women were so enraged by their husbands' actions that one evening they slew not only their husbands, but all the men of the island. Thereafter, Lemnos was a community of women without men, ruled by the virgin queen Hypsiple, until the day when Jason and the Argo arrived, which ended the period of celibacy and returned the island to heterosexual life.

Perfumes were not universally approved of in ancient Greece. Socrates, for example, objected to them altogether, noting, “There is the same smell in a gentleman and a slave, when both are perfumed,” and he believed that the only odors worth cultivating were those that arose from honorable toil and the “smell of gentility” (Morfit, 1847). Nevertheless,...