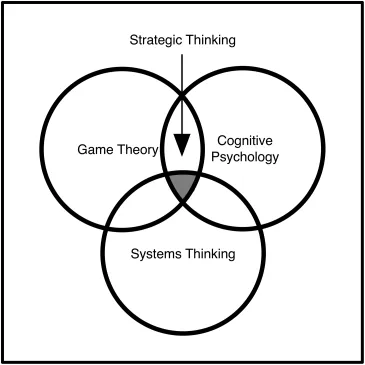

Achieving a meaningful understanding of strategic thinking involves addressing several interrelated topics. From an academic perspective, we see strategic thinking at the intersection of three fields of study: cognitive psychology, systems thinking, and game theory.

Cognitive psychology is the study of perception, creativity, decision making, and thinking. Systems thinking is an approach to understanding how systems behave, interact with their environment, and influence each other. Game theory is the study of decision making when the decision involves two or more parties (the decision maker and the opponent or adversary). While these are all academic disciplines, they address highly practical real-world matters. Applying cognitive psychology helps you manage your biases and blind spots. Systems thinking helps you broaden the slate of factors you consider when evaluating options and prioritizing actions. Game theory helps you further recognize the ramifications of your decisions and actions and take steps to mitigate opposing forces. We will now explore each of these disciplines in terms of how they influence and impact strategic thinking and strategic leadership.

Before we begin, we should note that the purpose of this chapter is not to provide an exhaustive review of the research that has been conducted in each of these three fields. Rather, our intent is to lay the foundation for subsequent chapters and provide enough information to raise your level of awareness of considerations impacting your ability to think and lead strategically.

Cognitive Psychology

The term cognitive psychology was first used in 1967.1 It is the branch of psychology that studies mental processes regarding how people perceive, solve problems, make decisions, and become motivated. Although cognitive psychology includes the study of memory and how individuals sense and interpret external stimuli, the most relevant elements for our purposes include how preconceived notions and beliefs influence and impact your analysis, the conclusions you draw, and the decisions you make. It also reveals the impact of mental models and processes on our focus, self-awareness, and awareness of the environment. Combined, these factors influence how we perceive our current reality, interpret existing and emerging opportunities, and imagine the future we desire.

In essence, cognitive psychology helps us explore and understand the way we interpret and interact with the environment. We consider this important because interpretation involves our grasping and analyzing information, and interaction involves our managing, altering, or manipulating our current or future environment.

Types of Discovery

The questions we ask are a key influence on how we interpret and interact with the environment. For example, what questions do we typically use when seeking to comprehend? When thinking about the future? When attempting to identify viable alternatives? A series of studies conducted by noted psychologist Jerome Bruner in the 1960s revealed that individuals have a natural tendency to ask certain types of questions when attempting to understand situations, events, and circumstances. His research revealed two types of questions, rooted in concepts called “episodic empiricism” and “cumulative constructionism.” Episodic empiricism is manifest in questions unrelated to or unbound by existing rules, laws, and principles—they are the questions typically used when attempting to make sense of the world and decide on a path forward. In this case, the question becomes the new hypothesis. Cumulative constructionism, on the other hand, manifests as questions intended to add clarity to existing understanding, paradigms, and structure.2 Put simply, some questions focus on “drilling down,” while others focus on “broadening.”

For example, consider the two types of questions that can be asked about a commercial-transport airplane crash. Cumulative constructionism–type questions, intended to drill down, might include:

- When did the crash occur?

- How far from the departure airport was the crash?

- How far from the arrival airport was the crash?

- Did the pilots declare an emergency prior to the crash?

- Were there any eyewitnesses to the crash?

- If there were eyewitnesses, what did they see?

- Was anyone on the ground injured or killed?

- Did the pilots deviate from the flight plan prior to the crash?

- Did the airplane strike a mountain or another airplane?

- Were there any survivors?

Episodic empiricism–type questions, asked to broaden one's thinking, might include:

- What type of material was the transport airplane carrying?

- What is the safety record of the company owning the airplane?

- What was the safety record of the flight crew?

- Who manufactured the airplane?

- What is the safety record of airplanes built by this particular manufacturer?

- How do all of the above compare to other airplanes, flight crews, and airplane manufacturers?

- How do all of the above compare to equipment, operators, and manufacturers in other industries?

Both lines of questioning are important. The value lies in understanding the difference and appropriate use of each.

From our perspective, the former type of questions are valid but will likely lead you down the current path to a certain conclusion and decision, albeit one with a greater level of detail. In contrast, the latter type of questions will likely lead you to a broader understanding and ultimately to a new and potentially more creative insight through considering more options.

The Role of Cognitive Ability

Another branch of cognitive psychology focuses on the role of intelligence in decision making and problem solving. While these activities are undoubtedly a component of strategy, we deemphasize the role of intelligence in strategic thinking and strategic leadership. Our stance is consistent with the conclusion that Bruner came to in his analysis of creativity:

Nothing has been said about ability, or abilities. What shall we say of energy, of combinatorial zest, of intelligence, of alertness, of perseverance? I shall say nothing about them. They are obviously important but, from a deeper point of view, they are also trivial. For at any level of energy or intelligence there can be more or less of creating in our sense. Stupid people create for each other as well as benefiting from what comes from afar. So too do slothful and torpid people. I have been speaking of creativity, not of genius.3

Creativity is manifest in a wide range of circumstances, independent of basic intelligence. Given this, we do not consider intelligence to play a distinguishing role in strategic thinking or strategic leadership. Instead, we consider several other cognitive characteristics to be important, including the following:

- The ability to recognize and take advantage of personal strengths and mitigate personal weaknesses,

- Comfort with and ability to understand complexity,

- The ability to recognize related concepts and principles,

- Self-confidence and belief in oneself,

- Comfort with ambiguity and uncertainty,

- A willingness to take risks,

- The courage of conviction,

- The willingness to draw conclusions and make decisions, and

- Personal assertiveness.

These cognitive characteristics consistently have been proven to correlate with creativity.4

We believe that cognitive activities associated with the creative process5 enable strategic thinking. These activities—while perhaps not always discrete or linear—typically include the following:

- Preparation:Becoming familiar with existing works, what has been done, how challenges are typically addressed, and how opportunities are typically seized.

- Incubation:Allocating time to the creative process, such that ideas and thoughts combine and awareness and understanding materialize.

- Insight:Combining existing concepts, principles, frameworks, and models to form new relationships, combinations, associations, or structures.

- Verification:Assessing and elaborating on new ideas to determine whether they are likely to be brought to fruition and molded into a complete product.

Types of Thought Processes

Whether your approach to problem solving and decision making involves sequential steps or taking intuitive leaps may depend partly on what research psychologist Gary Klein describes as System 1 and System 2 thinking.6 System 1 thinking involves applying instinct and intuition, which are in essence experience-based and expertise-driven. System 2 thinking involves applying and following preestablished steps and procedures. System 1 is somewhat unstructured, emergent, and omnidirectional, while System 2 is linear, somewhat rigidly sequenced, and unidirectional. While System 2 will help ensure you do not make serious mistakes in your logic or thinking, it alone is not enough. Much like the list of drill-down, cumulative construction–type questions we cited earlier, System 2 thinking alone proves inadequate in terms of raising, considering, and addressing the myriad issues in our complex, ambiguous, and uncertain world. System 1 thinking is much more effective at raisin...