Biological Sciences

Algal Toxins

Algal toxins are toxic substances produced by certain species of algae. When these toxins accumulate in water, they can pose serious health risks to humans and animals if ingested through contaminated seafood or water. Algal toxins can cause a range of health issues, including neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms, and can be particularly harmful to the liver and nervous system.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Algal Toxins"

- eBook - PDF

Marine Pharmacognosy

Action of Marine Biotoxins at the cellular level

- Dean Martin(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

C H A P T E R V Comparative Studies on Algal Toxins JOHN J. SASNER, JR. I. Introduction 7 A. Red Tides 8 B. Trophic Level Relationships 1 C. Biotoxins—Source 4 D. Biotoxins—Potential Utility 6 II. Experimental Procedure and Discussion 7 A. Laboratory Culturing 7 B. Bioassay 3 C. Physiological Methods 5 D. Pharmacology 3 III. Concluding Remarks 0 References * 7 * I. Introduction Biological productivity is the direct result of the conversion of solar energy by biochemical transducing mechanisms contained in autotrophic organisms called producers. In aquatic environments, the primary pro-ducers are the microscopic phytoplankton that bloom during periods when suitable nutrient and physical conditions exist. Photosynthetic producers constitute the basis of the food chain as well as the energy budget of fresh and salt water environments. The autotrophic microorganisms that play a vital role in productivity are also the source of many active chemical 127 128 John J. Sasner, Jr. substances. Some of these are extracellular products called external metab-olites or ectocrines (exocrines) (McLaughlin et al., 1960; Lucas, 1955; Collier, 1958; Aaronson et al., 1971). They may have antibacterial, anti-viral, or growth-inhibiting activity (Nigrelli et al., 1967; Baslow, 1969), and thus may affect other organisms at the same or higher trophic levels in the food chain. Extracellular products have been known for a long time, but only relatively recently has their potential importance to aquatic communities been discussed. Other active substances, called endotoxins, are synthesized and retained within the microorganisms, and they exert their effects when consumed and passed through the food chain or when released into the water by cell breakage. These endotoxic substances are some of the most potent materials known. - eBook - PDF

- William Helferich, Carl K. Winter(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Bac-terial toxins have the highest significance with respect to public health as well. Although mycotoxins have been responsible for individual acute poi-soning outbreaks, primary concerns regarding mycotoxin contamination in foods and feeds are related to both human illnesses due to long-term, low-level exposure and animal health. On the other hand, although there is a pau-city of information on aquatic biotoxins, contamination of seafoods with these toxins has the highest potential human health risks because of the wide-spread distribution of susceptible seafoods and the etiology of toxin produc-tion and subsequent accumulation. Aquatic Biotoxins in Seafood and Fresh Water Microscopic planktonic algae are used as a source of food for filter-feeding bivalve shellfish. When planktonic algae proliferate, i.e., form algal blooms, a beneficial effect for aquaculture and wild fisheries operations can be expected. However, these algal blooms may become harmful, affecting the economy of surrounding areas and causing human health impacts. 1 From the estimated 5000 species of marine phytoplankton, only around 300 can discolor the sur-face of the sea and around 40 can produce potent toxins that can enter the food chain through fish and shellfish to humans. 2 The term “red tide” is used when the algae grow in such abundance that they change the color of the seawater to red, brown, or green; however, the term is misleading because not all water discolorations are toxic. Therefore, the proper term is “harmful algal blooms” (HABs). 1,3 Although the organisms are often referred to as harmful algae, they include cyanobacteria as well as the almost animal-like Pfiesteria piscicida . 4 HABs are entirely natural phenomena which have occurred for years. However, the past 2 decades have been marked by increased frequency, intensity, and geographic distribution. This apparent increased in HABs can be explained by the following: 1. - eBook - ePub

- Bernardo Duarte, Maria Isabel Violante Caçador, Bernardo Duarte, Maria Isabel Violante Caçador(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

4 Effects of Harmful Algal Bloom Toxins on Marine OrganismsLopes, V.M.,1 ,2 ,* Costa, P.R.2 ,3and Rosa, R.11 MARE – Marine Environmental Sciences Centre, Laboratório Marítimo da Guia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal.2 IPMA – Portuguese Institute for the Sea and Atmosphere, Avenida de Brasília, 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal.3 CCMAR – University of Algarve, Campus of Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal.* Corresponding author: [email protected]INTRODUCTION

Phytoplanktonic communities are vital to marine ecosystems. These communities constitute the basis of marine food webs throughout the planet, providing food for filter-feeding organisms, such as bivalves and planktivorous fish and also a number of vertebrate and invertebrate larval stages. Algal blooms are natural occurrences, defined as the sudden overgrowth of microscopic algae under optimal environmental conditions, reaching up to millions of cells per litre (Hallegraeff 1993). These blooms are typically beneficial for the ecosystem, increasing feeding opportunities for countless organisms. However, if toxin-producing microalgae undergo this sudden overgrowth, it can lead to harmful algal blooms (HABs). Despite the fact that approximately 2 percent of microalgae species produce toxins (Hallegraeff 2014, Smayda 1997), HABs can significantly impact marine communities.In the marine realm, the majority of HAB-toxins are produced by dinoflagellates and diatoms (Table 1 - eBook - PDF

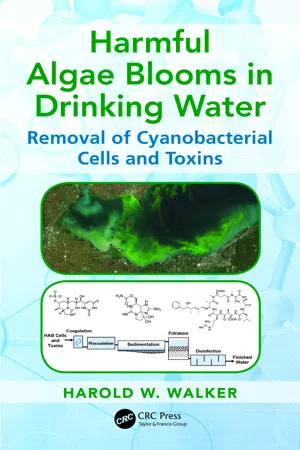

Harmful Algae Blooms in Drinking Water

Removal of Cyanobacterial Cells and Toxins

- Harold W. Walker(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

27 3 Toxin Properties, Toxicity, and Health Effects 3.1 Introduction Harmful algal blooms (HABs) and their associated toxins are a significant threat to human health. Cyanobacteria and other HAB organisms produce a variety of toxins, including neurotoxins, hepatotoxins, dermatotoxins, and other bioactive compounds. As discussed in Chapter 1, the most typically cited classes of HAB toxins include microcystins, saxitoxins (STXs), ana-toxins, and cylindrospermopsin. Although complete understanding of the health effects of HABs and HAB toxins has not yet been developed, HAB toxins are known to cause a variety of short- and long-term health effects in animals and humans. In natural systems, HABs result in fish kills and may lead to death or acute health effects in animals and livestock. Short- term acute effects of HAB toxins on humans include rashes, liver inflam-mation, numbness, dermatitis, gastrointestinal problems, liver failure, and others. Documented longer-term impacts associated with low-level chronic exposure to HAB toxins are less well known but potentially include tumor formation, cardiac arrhythmia, and liver failure. From a risk assessment perspective, it is important to identify the vari-ous factors and processes that define the risk associated with contact to HABs and HAB toxins, in terms of both human health and the environment. As a general framework, it is important to identify sensitive populations, elucidate the fate and transport of HAB cells or toxins in natural or engi-neered systems, understand the significance of different routes of exposure, and ultimately understand the toxicity of the compounds or other health effects on contact. Many of the known cases of poisoning by HABs or HAB toxins occurred in populations of more sensitive individuals, such as chil-dren or people undergoing dialysis. During a bloom, the HAB cells or toxins often must be transported in the water column to come into contact with humans or animals. - eBook - PDF

Seafood and Freshwater Toxins

Pharmacology, Physiology, and Detection, Third Edition

- Luis M. Botana(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

1073 38 Marine Cyanobacterial Toxins: Source, Chemistry, Toxicology, Pharmacology, and Detection Vitor Vasconcelos and Pedro Leão 38.1 Introduction Cyanobacterial toxins or cyanotoxins have been studied for the past decades mostly due to the fact that they may cause severe human and animal intoxications when present in freshwaters used for drinking, recreation, or dialysis (Jochimsen et al., 1998; Chorus and Bartram, 1999). Although cyanotoxins may be taken up by freshwater organisms such as mussels, crustaceans, or fish, there is now record or evidences that intake via food may cause severe human intoxications as it occurs in the marine environment with the toxins associated with harmful algal blooms (HABs). Cyanobacteria may produce a wide array of cyanotoxins, being classified, accordingly to the main effects in mammals, hepatotoxins, neurotoxins, cytotoxins, and dermatotoxins (Chorus and Bartram, 1999). Many other secondary metabolites have been described, some with allelopathic properties (Leão et al. 2010, 2012) or being active against virus, bacteria, and cancer cells (Martins et al., 2008; Herfindal et al., 2010; Lopes et al., 2011), but for most of them, no toxicity against CONTENTS 38.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1073 38.2 Sources ........................................................................................................................................ 1074 38.2.1 Palytoxin ......................................................................................................................... 1074 38.2.2 Lyngbyatoxin .................................................................................................................. 1075 38.2.3 Nodularins and Microcystins ......................................................................................... - eBook - ePub

- J P F D'Mello(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CAB International(Publisher)

It is generally assumed that biogenic compounds arise as a result of secondary metabolism in microorganisms and plants. Such an assumption implies an inferior function to the primary metabolism involved in respiration, photosynthesis and protein accretion. However, there is accumulating evidence that secondary compounds serve crucial roles in defence and competition for survival and growth in particular niches and ecosystems. This aspect is viewed positively, for example, by those advocating the replacement of synthetic chemicals with an appropriate selection of plant secondary compounds to serve as environmentally friendly ‘biopesticides’ in arable farming. On the negative side, a relatively significant number of biogenic compounds are capable of inducing moderate to severe toxicity in humans and animals following contamination of staple foods and drinking water.2.2 Algal ToxinsThe distribution of algal blooms is increasing at an unprecedent pace in response to climate change, higher rainfall and run-off of fertilizers from farmland. A recent survey indicated a significant increase in 33 countries worldwide. Algae emitting hydrogen sulfide contaminating the coastline around parts of Brittany in 2019 contributed to the deaths of three people inhaling the gas. In Bolivia, the first recorded algal bloom occurred in 2015 in a high-altitude lake which subsequently was observed to exacerbate hydrogen sulfide and methylmercury contamination in this remote aquatic ecosystem.A group of Gram-negative photosynthetic blue-green algae, named cyanobacteria, occur in a wide range of ecosystems, from freshwater rivers and lakes to oceans, but may also exist in hot springs and in arid regions such as deserts. They are frequently seen as blooms and scums within and on the surface of water, often appearing as macroscopic formations, visible to the naked eye and causing aesthetic issues as well as the potential to induce toxicity in humans and wildlife through exposure to cyanobacterial toxins (see Case Study 2.1 and Fig. 2.1 ).Fig. 2.1. - eBook - ePub

- S.J.S. Flora, Vidhu Pachauri(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Natural toxins or biotoxins are substances produced by one organism that elicit their toxic action on another organism. Toxins are extremely poisonous products of the metabolism of living organisms like bacteria, plants, animals, and fungi. Biotoxins are individual chemical compounds of natural origin. These are biologically active chemical compounds or compounds produced by a specific chemical mechanism in a living organism. Chemically, they are a wide variety of complex structures like proteins, cyclic peptides, alkaloids, etc. After knowing the structure, toxins can be prepared by chemical synthesis in desired quantities. Some toxins can also be prepared by biotechnological procedures like cloning and expression. Toxins, from a pharmacological and toxicological perspective, can be considered chemical weapons. Comparison of physicochemical and functional characteristics place toxins between chemical warfare agents and biological warfare agents. There are several differences between toxins and traditional chemical warfare agents. When compared, toxins have a higher molecular weight, most of them are odorless and not dermally active, and most of them produce immune responses in the host. Toxins are easy to use via inhalation route in the form of aerosols. Their toxicity potential is much higher than highly toxic chemical agents like sarin. As a comparison, the lethal inhalation concentration (LCt50) of a botulinum toxin aerosol, on average, is 1000 times more toxic than sarin vapor. Toxic substances based weapons have a long history of several thousand years. It is associated with traditional methods of hunting, including the use of poisoned arrows, water, or the fumigation of animals with toxic combustion products. All of these hunting forms involving toxic substances were developed for ancient wars. In some form or other, these have persisted until now. Toxins from plants, animals, bacteria, cyanobacteria, algae, and fungi have been used by man for fighting and hunting purposes since the earliest times. Some toxins, such as ricin (W), botulinum toxin (X), or saxitoxin (TZ), were formerly proposed as standard fillings for military ammunition. Intensive military research activity was carried out on some toxins like palytoxin, batrachotoxin, and tetrodotoxin.Keywords

Toxins; Harmful algal blooms (HAB); Conotoxin; Dinoflagellates; Diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS); Tetrodotoxin (TTX)Introduction

Natural toxins or biotoxins are substances produced by one organism that elicit their toxic action on another organism. Toxins are extremely poisonous products of the metabolism of living organisms like bacteria, plants, animals, and fungi. Biotoxins are individual chemical compounds of natural origin. These are biologically active chemical compounds or compounds produced by a specific chemical mechanism in a living organism. Chemically, they are a wide variety of complex structures like proteins, cyclic peptides, alkaloids, etc. After knowing the structure, toxins can be prepared by chemical synthesis in desired quantities. Some toxins can also be prepared by biotechnological procedures like cloning and expression. Toxins, from a pharmacological and toxicological perspective, can be considered chemical weapons (Anderson, 2012a ). Comparison of physicochemical and functional characteristics place toxins between chemical warfare agents and biological warfare agents. There are several differences between toxins and traditional chemical warfare agents. When compared, toxins have a higher molecular weight, most of them are odorless and not dermally active, and most of them produce immune responses in the host. Toxins are easy to use via inhalation route in the form of aerosols. Their toxicity potential is much higher than highly toxic chemical agents like sarin. As a comparison, the lethal inhalation concentration (LCt50) of a botulinum toxin aerosol, on average, is 1000 times more toxic than sarin vapor. Toxic substances based weapons have a long history of several thousand years. It is associated with traditional methods of hunting, including the use of poisoned arrows, water, or the fumigation of animals with toxic combustion products. All of these hunting forms involving toxic substances were developed for ancient wars. In some form or other, these have persisted until now. Toxins from plants, animals, bacteria, cyanobacteria, algae, and fungi have been used by man for fighting and hunting purposes since the earliest times. Some toxins, such as ricin (W), botulinum toxin (X), or saxitoxin (TZ), were formerly proposed as standard fillings for military ammunition. Intensive military research activity was carried out on some toxins like palytoxin, batrachotoxin, and tetrodotoxin (Pitschmann, 2014 - eBook - PDF

- Tõnu Püssa(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

255 © 2011 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC 12 Food Toxicants from Aquatic Animals 12.1 INTRODUCTION Only a few species out of the numerous toxin-containing organisms (about 1200 known species) living in the sea have something to do with food toxicology. Toxic compounds are produced either by • The edible organisms (fish and shellfish) themselves or • The sea phytoplankton or algae, ingested by the edible fish or shell-fish. This group of toxic substances is called phycotoxins , from Greek, j tildenosp U o κ ς = phykos , “alga”; and toxikon , “toxin.” The microorganisms inhabiting water are actually the main culprits of food intoxications caused by the consumption of most crustaceans (shellfish) and fish. To estimate the potential toxicity of seafood, various functional assays have been developed (Rossini, 2005). A recent review on toxicity and risk assessment data on the main marine biotoxins has been published by Paredes et al. (2011). 12.2 SHELLFISH TOXICANTS Various organisms belonging to the class of shellfish (crustaceans) such as clams, lobsters, mussels, oysters, scallops, and so forth, which have ingested toxic algae, particularly dinoflagellates, can be highly toxic. Shellfish are especially toxic dur-ing intensive blooming of algae, when seawater contains 200 or more poisonous microorganisms per milliliter. The toxicity of shellfish is proportional to the con-centration of algae in water and disappears over 2 weeks after the disappearance of the toxic phytoplankton. Shellfish poisonings are divided into four groups— paralytic , diarrhetic , neurotoxic , and amnesic . 12.2.1 Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning The toxicants that cause paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) include more than 20 structurally related imidazoline–guanidinium alkaloids produced by a number - eBook - PDF

Toxins and Biologically Active Compounds from Microalgae, Volume 2

Biological Effects and Risk Management

- Gian Paolo Rossini(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

In 2005, a total of 209 subjects matched the case definition for Algal Syndrome. The clinical 368 Toxins and Biologically Active Compounds from Microalgae Volume 2 Fig. 1. Reports of “Algal Syndrome” after inhalational and/or dermal exposure to seawater and/or seawater aerosols during blooms of Ostreopsis spp. in Europe. Information from Tubaro et al. (2011b). Toxicity of Palytoxins: From Cellular to Organism Level Responses 369 symptoms most often associated with these events included fever, irritative symptoms of the upper and lower respiratory tracts and conjunctives. Clinical laboratory analysis during the acute phase of 82 patients showed a significant finding of mild leucocytosis (mean white cell count: 13,900 ± 3,400/mm 3 ; range: 10,100–23,900/mm 3 ) and neutrophilia (mean: 82.2 ± 4.7%; range: 75.2–91.5 %) in 46.3% and 40.2% of the cases, respectively (Durando et al. 2007). Tichadou et al. (2010) described several cases involving flu-like symptoms including headache, joint pain, vertigo, fever, fatigue, and, in some cases, digestive discomfort and diarrhea in recreational divers swimming in waters containing varying concentrations of O. ovata in both France and Monaco (Fig. 1). All together over 650 cases fitting the description of “Algal Syndrome” have now been reported throughout the northern Mediterranean and Adriatic seas in association with exposure to waters containing Ostreopsis spp. (Fig. 1). The concentrations of PlTX and/or PlTX-like compounds required to cause these effects through inhalational, dermal, and ocular exposures are still unknown. Linking Cellular Toxicity Studies to Acute Toxicity in Humans Because of the ability to acquire high concentrations of PlTX from some zoanthids, which led to greater than normal availability for a new toxin for research, coupled with its extreme potency, PlTX has been utilized extensively over the years as a model compound in standard cellular systems (for review see Vale (2008)). - eBook - PDF

- John Gilbert, Hamide Şenyuva, John Gilbert, Hamide ?enyuva, Hamide Şenyuva(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

and Green, D.H. (2006) Relationships between bacteria and harmful algae, in Ecology of Harmful Algae. Vol. 189: Ecological Studies (eds. E. Gran´ eli and J.T. Turner). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 243–255. Kong, K., Moussa, Z. and Romo, D. (2005) Studies toward a marine toxin immunogen: Enantioselective synthesis of the spirocyclic imine of ( − )-gymnodimine. Organic Letters , 7 (23), 5127–5130. Phycotoxins in Seafood 103 Kotaki, Y., Koike, K., Yoshida, M., Thuoc, C.V., Huyen, N.T.M., Hoi, N.C., Fukuyo, Y. and Kodama, M. (2000) Domoic acid production in Nitzschia sp . (Bacillariophyceae) isolated from a shrimp-culture pond in Do Son, Vietnam. Journal of Phycology , 36 (6), 1057–1060. Kotaki, Y., Lundholm, N., Onodera, H., Kobayashi, K., Bajarias, F.F.A., Furio, E.F., Iwataki, M., Fukuyo, Y. and Kodama, M. (2004) Wide distribution of Nitzschia navis-varingica , a new domoic acid-producing benthic diatom found in Vietnam. Fisheries Science , 70 (1), 28–32. Kuiper-Goodman, T., Falconer, I.R. and Fitzgerald, J. (1999) Human health aspects, in Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water (eds. I. Chorus and J. Bartram). E. and F.N. Spon, London, pp. 113–153. Kulagina, N.V., Twiner, M.J., Hess, P., McMahon, T., Satake, M., Yasumoto, T., Ramsdell, J.S., Doucette, G.J., Ma, W. and O’Shaughnessy, T.J. (2006) Azaspiracid -1 inhibits bioelectrical activity of spinal cord neuronal networks. Toxicon , 47 (7), 766–773. Kuramoto, M., Arimoto, H. and Uemura, D. (2004) Bioactive alkaloids from the sea: A review. Marine Drugs , 1 , 39–54. Kvasnicka, F., Sevcik, R. and Voldrich, M. (2006) Determination of domoic acid by on-line coupled capillary isotachophoresis with capillary zone electrophoresis. Journal of Chromatography A , 1113 (1–2), 255–258. Lansberg, J.H. (2002) The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Reviews in Fisheries Science , 10 (2), 113–390. Lawrence, J.F., Maher, M.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.