Biological Sciences

Energy Transfers

Energy transfers in biological systems involve the movement of energy from one organism to another or within an organism's cells. This process is essential for sustaining life, as it allows organisms to carry out vital functions such as growth, reproduction, and metabolism. Energy transfers can occur through processes like photosynthesis, respiration, and food consumption.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Energy Transfers"

- eBook - ePub

Biomolecules

From Genes to Proteins

- Shikha Kaushik, Anju Singh(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

Chapter 4 Concept of Energy in BiosystemsThe highly structured and organized nature of living systems is perceptible and astonishing. Growth, development, and metabolism are some of the fundamental processes that occur in living organisms, and the role of energy is fundamental to all these biological processes. The survival of any living organism depends on energy transformations, that is, the exchange of energy within and without a particular system. The fundamental matter in bioenergetics, that is, the study of energy relationships and conversions in living organisms, signifies the way by which energy from fuel metabolism or by capturing light is coupled to the energy-requiring reactions occurring in the cell. Muscular contraction, synthetic reactions, and active transport are some of the important processes that get energy when linked or coupled with some energy-releasing reactions (exergonic reactions). In all organisms (autotrophic and heterotrophic), ATP (adenosine triphosphate) plays an important role in transferring energy from the exergonic to the endergonic reactions. ATP is called a high-energy phosphate compound and is produced by living organisms via oxidative phosphorylation. The terminal phosphate linkage in ATP is relatively weak; when broken, it yields adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and inorganic phosphate and releases a large amount of energy. An organism’s stockpile of ATP is used by the cells to perform different activities to sustain life, and energy released from rearrangement of bonds within molecules is utilized to power all biological processes in every organism.Bioenergetics or biochemical thermodynamics deals with the transformations, exchange, requirements, and processing of energy within living systems. It also focuses on how cells transfer energy. Some of the essential biological processes such as biosynthesis of nucleic acids and other biomolecules are not thermodynamically favored under provided conditions, as they require an input of energy. They can proceed if coupled with energy-releasing processes. So, it endows with the answer why some reactions may occur while others do not. - eBook - PDF

- Harold Morowitz(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

We are thus able to make contact between thermodynamics and the study of energy flow in ecology. So far we have dealt with rather general considerations of radiant and chemical energy. Other terms in the internal energy such as charge transfer, surface energy, and osmotic work are of major importance in biology. In the next chapter we present some approaches used to deal with these topics. BILIOGRAPHY Krebs, H. A., and Kornberg, H. L., Energy Transformations in Living Matter. Springer, New York, 1957. A detailed review of the relation of intermediary metabolism to bioenergetics. Lehninger, A. L., Biochemistry. Worth Publ., New York, 1975. This very extensive textbook of biochemistry details the metabolic pathways involved in bio-energetics and discusses various aspects of the subject. Morowitz, H. J., Energy Flow in Biology, Academic Press, New York, 1968. Much of this chapter comes from Chapter IV of this work. Slobodkin, L. B., Growth and Regulation of Animal Populations. Holt, New York, 1961. Chapter 12 discusses the efficiency of predator-prey energy conversions. Watt, B. K., and Merrill, A. L., Composition of Foods. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., 1963. Contains extensive data on heats of combustion of a wide variety of biological materials. - eBook - PDF

Survey of Progress in Chemistry

Volume 1

- Arthur F. Scott(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The Chemistry of Biological Energy Transfer W I L L I A M P. J E N C K S Graduate Department of Biochemistry, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts I. Introduction 249 II. T e r m i n o l o g y and S o m e E x a m p l e s 251 III. T h e Source of U s e f u l E n e r g y in Biological S y s t e m s 256 A. S u b s t r a t e Level P h o s p h o r y l a t i o n 257 B . Oxidative P h o s p h o r y l a t i o n 261 C. P h o t o s y n t h e s i s 265 IV. Group T r a n s f e r Reactions 267 A . P h o s p h a t e T r a n s f e r 267 B. A c y l T r a n s f e r 273 C. T r a n s f e r s of A l d e h y d e a n d K e t o n e Groups 277 D . A l k y l Group T r a n s f e r s 281 E . Other S i m p l e T r a n s f e r R e a c t i o n s 283 F . Complex Group T r a n s f e r and A c t i v a t i o n Reactions 288 V. Utilization of Chemical E n e r g y 294 A. Muscle Contraction 295 B. T r a n s p o r t of E l e c t r o l y t e s a n d O r g a n i c C o m p o u n d s a c r o s s M e m b r a n e s 297 C. N e r v e Conduction and Generation of Electricity 297 D . Bioluminescence 298 V I . F u t u r e D e v e l o p m e n t s 298 R e f e r e n c e s 299 I. Introduction With the exception of the work of those unusual scientists who intro-duce new concepts into a field of investigation, the nature of the research which is carried out in a given area at a given time is molded by the 2 4 9 250 WILLIAM P. JENCKS prevailing concepts of that time. In order to provide a perspective for a discussion of present knowledge of the mechanisms by which metabolic energy is generated, transferred, and utilized, it is of some interest to survey earlier conceptions of these processes. Aristotle presented one of the earliest mechanistic interpretations of the functioning of a warm-blooded organism when he held that the pur-pose of breathing air is simply to cool the blood. - eBook - PDF

- H W Doelle(Author)

- 1994(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6 C e l l T h e r m o d y n a m i c s 1. Concept of thermodynamics of biological systems One of the most fundamental properties of l i v i n g c e l l systems is their a b i l i t y to u t i l i z e and transform energy. This energy occurs in a number of forms: Mechanical Energy is developed during cellular movement, beating of flagella, reorganization of intracellular structures such as mitochondria, and alteration of c e l l shape; Electrical Energy is produced when electrons move from one place to another, usually expressed as a flow of current between two points due to a difference in voltage; Electromagnetic Energy occurs in the form of radiation, and in biology the most significant is that from visible or near-visible light, such as radiation from the sun for photosynthet-ic organisms. Some organisms release energy and glow, which i s referred to as bioluminescence. They produce light energy. Chemical Energy is the energy that can be released from chemical reactions; Thermal Energy or heat is produced as part of the normal energy transformation processes and occurs as waste energy released into the surroundings; Atomic Energy i s contained within the structure of atoms themselves and is released in the form of atomic radiation, which can not be u t i l i z e d by living organisms. Since growth can be defined as the orderly increase of a l l chemical components, i t is the chemical form of energy which is of greatest importance for the understanding of microbial growth and metabolism. Microbial metabolism consists of thousands of individual chemical and enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions. These chemical reactions in l i v i n g organisms occur in characteristi-cally organized sequences, called metabolic pathways. There are two main types of metabolic pathways: (a) pathways which lead from large (low oxidative state) to smaller molecules (high oxidative state), which are called catabolic pathways or catabolism. 91 - eBook - PDF

- William J. L. Felts, Richard J Harrison, William J. L. Felts, Richard J Harrison(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The author realizes that many applications of heat transfer to biological systems have been made to man, animals, and plants. In the course of our examination, we shall not be concerned with heat transfer from man. In order to facilitate our discussions of past works, it is convenient to break the area down into two parts, ( 1 ) internal energy or heat generation—metabolism, and (2) external energy transfer from the organism to the surrounding environment. The latter will be of most concern to us in this paper. A. METABOLISM The first efforts in this area were concerned with the study of metabolic rates of various animals in resting states; as time went on, research progressed to include the effects of nutritional levels, age, sex, environ- mental air temperature, seasonal changes, and other parameters. The vari- JHEORETICAL ^^UMJENERGY JN_TAKEJ_E\/El_ REPRESENTATIVE LEVELS OF ENERGY INTAKE RESTING METABOLISM MINIMUM EXTENDED MAINTENANCE LEVEL BASAL METABOLISM ^ * < MINIMUM MAINTENANCE | LEVEL THERMONEUTRAL I RANGE , I i I T cu T +, ENVIRONMENTAL TEMPERATURE Fig. 1. Graph of heat production, environmental temperature, and energy intake relationships. (Adapted in part from Kling and Farner (1961), p. 236; Kleiber (1961), pp. 163 and 274). TV.L and Tcu represents a theoretical range of thermoneutrality, above and below which heat production is increased. Because of the calorigenic effect of food, the lower critical temperature is extended downward (T-i) for nonfasting individuals on maintenance level of heat production. At higher energy intake levels, lower environmental temperatures can be tolerated because the increased heat production will compensate for the associated increased heat loss, until the lower lethal level (T-*) is reached. Heat Transfer in Biological Systems 271 ous parameters affecting metabolism are given by Benedict (1938), Brody (1945), Giaja (1938), Klieber (1961), Scholander et al (1950), King and Farner (1961), as well as others. - eBook - PDF

Ecology

Principles and Applications

- J. L. Chapman, M. J. Reiss(Authors)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

TWELVE Energy transfer 12.1 Energy and disorder Living organisms are highly organised. In order to survive and maintain this internal order organisms need supplies of the relevant nutrients, a source of energy and the ability to create a large amount of disorder outside themselves. This last requirement may sound rather odd, but the second law of thermodynamics states that the amount of disorder in a closed system, such as the universe, increases with time. For organisms to create order, as they do when they make new cells, they need energy and/or the ability to create disorder outside themselves. Respiration both releases energy and creates disorder as relatively large molecules, such as glucose, are broken down to smaller and therefore less ordered molecules, i.e. carbon dioxide and water. The trophic levels at which species feed have been considered in Chapter 11, and Chapter 13 will look at how organisms obtain the nutrients they need. This chapter aims to look quantitatively at how organisms obtain their energy and how they pass energy up a food chain. Because the vast majority of primary production in the world is the result of photosynthesis rather than chemosynthesis, we will first examine the environmental factors that determine the amount of photosynthesis in different communities. We will then see whether there are any ecological rules governing the transfer, or movement, of this energy up a food web through the trophic levels. 12.2 Primary production in terrestrial communities When autotrophs photosynthesise, they turn carbon dioxide and water into larger structural molecules which allow the plant to increase in size. Gross primary productivity is a measure of the total amount of dry matter made by a plant in photosynthesis. It is measured in units of dry weight per unit area per unit time. - eBook - PDF

- John Wrigglesworth(Author)

- 1997(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

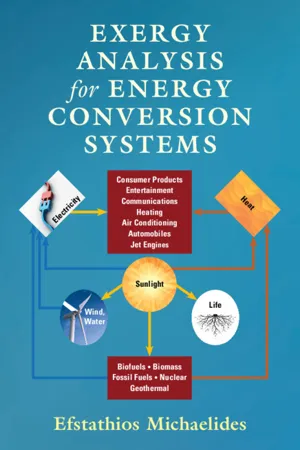

1 Introduction to Bioenergetics Two CONDITIO NS NECESSARY FOR LIFE • Mechanism(s) for the control of energy flow • Systems for informa-tion storage and transmiss ion 1.1 Life and ener gy Energy flow is essential for life and bioenergetics describes how living systems capture, transform and use energy. Almost immediately we meet a problem which turns most students away from the subject. The concept of energy is not an easy one. Definitions are very abstrac t, 'the capa city to do work', 'the energy of an object by virtue of its position', the 'rest-mass energy' of an object. In fact we real ly have no knowledg e of what energy is. Another awkward fact is tha t energy also seems to exist in many different forms. We can speak of potential energy, kinetic energy, heat energy, elec-trical energy, chemical energy, radiant energy, nuclear energy, and ev en 'information ' en ergy. Certain observational facts or laws, the laws of thermodynamics, allow us to do various calculations about energy and energy transforma-tions but these do not lead us any closer to the abstract thing tha t is called energy. Nevertheless, the conti nuous flow of energy through organisms is required for life. A second requirement for life, which is probably easier to imagine, is some method of storing information and passing the knowledge from one generation to the next. We know how this works quite well. The information is stored in the linear sequence of bases in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the form of the genetic code. Replication of DNA occurs to transmit the informatio n from one generation to the next. The production of ribonucleic acid (RNA) (transcription) and protein (translatio n) allows this informatio n to be used for the essential functions of life. Nevertheless, althoug h an information system is necessary for life it is not sufficient on its own. For example, we do not think of viruses as living systems although they have a very efficient informatio n sto-rage system. - Efstathios Michaelides(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The foods-to- Figure 5.5 The vital processes in an animal body as an open thermodynamic system. 214 Exergy in Biological Systems nutrients conversion processes in the animal bodies are analogous to the industrial production of secondary and tertiary energy forms, such as petroleum refinement and electricity. The food residue and wastes of the digestive process are egested in the feces, which also carry a small part of undigested nutrients (5–10%). The digestive system communicates through permeable cell membranes and transfers the secondary energy forms, the nutrients, to the blood circulation system, which is powered by the heart – a pump made of soft tissue. The circulatory system also communicates with the respiratory system through the lungs, – organs with very large and semipermeable membrane area, through which oxygen diffuses into the blood stream and carbon dioxide diffuses out to be exhaled. Oxygen in the blood stream combines with the nutrients in the blood and the oxidation process produces the body heat, which maintains the temperature of the body. All this heat is transferred to the surroundings. In addition, the oxidation process generates biochemical compounds that provide energy to the tissues of all the organs in the body – heart, liver, breathing muscles, kidneys, muscles, etc. – and enable them to perform the mechanical work, which is necessary for all the processes that define life. In summary, the animal (including human) bodies are open thermodynamic systems that receive chemical energy in the form of food and, through numerous biochemical processes convert this energy to heat and work. 5.4.1 Energy Inputs Food is the fuel of all animals. The chemical energy of the several types of foodstuff we eat and digest is converted to derivative chemicals that provide the energy of the human body. The basic chemical compounds that make up the human food are classified as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.- eBook - ePub

Bioenergetics

A Bridge across Life and Universe

- Davor Juretic(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Chapter 16 , sections 10 and 11).9.2 Efficiency of biological processes

For convenience, we shall repeat here the definitions from Chapter 3 pertaining to efficiency. When speaking about biological processes’ efficiency, it is important to distinguish free-energy storage efficiency from free-energy transduction efficiency. These two efficiencies are connected. Energy storage efficiency is the ratio of output to the input force. This ratio is already contained as the –X2 /X1 expression from Chapter 3 equation for the free-energy transduction efficiency:We have seen in the case of linear relationships between forces and fluxes that maximal energy storage efficiency is obtained when maximal output force X2 is achieved in the static head steady state, but the output flux J2 vanishes in that case (J2 = 0). In a linear case, it is not possible to achieve at the same time a maximal free-energy storage efficiency and non-zero free-energy transduction efficiency. There is no trade-off between maximal energy storage and non-vanishing energy conversion. The same principle holds for nonlinear energy conversions. For example, the living cell cannot convert free energy into a more suitable form while storing a maximum possible amount of free energy for future needs. It is like an impossibility to eat the cake and save it at the same time for tomorrow’s delight. If storage efficiency is maximal, the conversion efficiency is precisely zero.η = −.J 2X 2J 1X 1We have learned from bioenergetics the nature of the most important output force produced and maintained during photosynthesis and respiration. The protonmotive force is the output force, while either photosynthesis or respiration provides the driving force. The photon free energy is used to perform charge separation during photosynthesis. Life diversification, the emergence of multicellular organisms, and accelerated biological evolution became possible when life learned how to use the photon free energy. Only a small percentage of photon free energy suffices to create an optimal (but not the maximal) protonmotive force. The major part of proton free-energy is dissipated, that is, exported as useless heat to the environment. However, the protonmotive force and nonzero free-energy conversion efficiency cannot be maintained without the continuous destruction of free energy packages. An optimal electrochemical proton gradient is then converted into ATP synthesis. All subsequent uphill biochemical reactions require ATP hydrolysis. In the case of an active bacterial cell, the cell is effectively dead in seconds after the ATP synthesis stops. ATP molecules are never stored in the cells, and synthesis-hydrolysis cycles, needing ATP hydrolysis, take place at the breakneck pace.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.