Biological Sciences

Gut Brain Axis

The gut-brain axis refers to the bidirectional communication system between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. It involves the complex interplay of neural, hormonal, and immunological signaling pathways. This axis plays a crucial role in regulating various physiological processes, including digestion, metabolism, and even cognitive functions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Gut Brain Axis"

- eBook - ePub

- Daniel K. Podolsky, Michael Camilleri, J. Gregory Fitz, Anthony N. Kalloo, Fergus Shanahan, Timothy C. Wang, Daniel K. Podolsky, Michael Camilleri, J. Gregory Fitz, Anthony N. Kalloo, Fergus Shanahan, Timothy C. Wang(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Arguably, the most unequivocal evidence of the brain's influence on human GI function derives from reports of alterations of this function caused by lesions within the central nervous system (CNS). The most frequently encountered clinical example is dysphagia following a cerebrovascular accident [5]. A further example is gastric emptying delay occurring as a sequelae of spinal cord transection or constipation related to Parkinson disease [6,7]. Despite these insights, it was not until the late 1980s/early 1990s and the advent of the mainstream use of a number of noninvasive neurophysiological techniques, that these interactions have been studied noninvasively in vivo in health and disease. These technological developments have led to advances in our understanding of the sensorimotor pathways between the brain, the periphery, and the CNS. This increased understanding has led to the development of the concept of the brain–gut axis, a bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain, which has gained widespread acceptance as the construct providing an explanation of normal function, and acute and chronic perturbations, of GI function. Moreover, this model of bidirectional communication has provided a biological framework to underpin the biopsychosocial concept of GI disorders by facilitating the integration of many contributing factors whether they are biological, psychological, or social in nature.This chapter first reviews the salient functional anatomy and physiology of the brain–gut axis, and then examines the interactions of the brain–gut axis with the GI microbiome, appetite/satiety regulation, autonomic nervous system, and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Finally, alterations in the brain–gut axis and their clinical implications are considered.Gut to Brain Communication

Intrinsic Innervation – The Enteric Nervous System

The GI tract has substantial sensory innervation [8]. These sensory afferents convey information to the CNS, facilitating coordination and integration of reflex function with behavioral responses in addition to mediating sensation [9]. The intrinsic innervation of the GI tract, known as the enteric nervous system (ENS), can direct and sustain GI function even after connections to the CNS have been severed. As depicted in Figure 14.1 , the ENS comprises of the myenteric and submucosal plexi and controls gut motility, secretory and endocrine functions that are required for normal digestive processes (see Chapter 15 - eBook - ePub

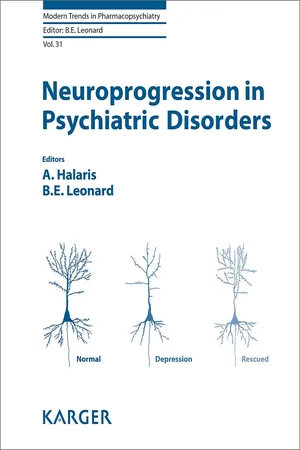

- A. Halaris, B. E. Leonard, A., Halaris, B.E., Leonard, Brian E. Leonard, Brian E., Leonard(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- S. Karger(Publisher)

Copyright © 2013 S. Karger AG, BaselOver the past decade there has been an exponential increase in research focusing on the braingut axis because of its potential role in a variety of disorders, not just relating to irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease, but also involvement in mood disorders. In this review we will explore the impact of stress on the brain-gut axis and the possibility of targeting the axis for the treatment of stress related disorders such as depression.Studies of this brain-gut axis now of necessity include the gut microbiota, which in many respects is a metabolic organ in its own right. The general scaffolding of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis includes the central nervous system (CNS), the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems, the sympathetic and parasympathetic arms of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the enteric nervous system (ENS) and the intestinal microbiota. These components interact to form a complex reflex network with afferent fibres that project to integrative CNS structures and efferent projections to the smooth muscle [1 ]. Through this bidirectional communication network, signals from the brain can influence the motor, sensory and secretory modalities of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and, conversely, visceral messages from the gut can influence brain function [1 ]. Less well studied but increasingly appreciated is the potential impact of the enteric microbiota on the relationships within the construct [2 , 3 ] and the realisation it may play a part in CNS disorders such as major depression.Microbiota Composition and Development

The GIT is inhabited with 1013 —1014 microorganisms, a figure thought to be ten times that of the number of human cells in our bodies and 150 times as many genes as our genome [4 , 5 ]. The estimated species number varies greatly but it is generally accepted that the adult microbiome consists of greater than 1,000 species [6 ] and more than 7,000 strains [7 ]. It is an environment dominated by bacteria, mainly strict anaerobes, but also including viruses, protozoa, archae and fungi [8 ]. The microbiome is largely defined by 2 bacterial phylotypes, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes with Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria , and Verrucomicrobia phyla present in relatively low abundance [9 - eBook - PDF

Gut Microbiota

Brain Axis

- Alper Evrensel, Bar?? Önen Ünsalver, Barış Önen Ünsalver, Alper Evrensel, Barış Önen Ünsalver(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

Technology addiction is causing problems in the physical, psychological, social, and cognitive developments of children and youth [ 15–17]. As a result Gut Microbiota - Brain Axis 40 of the studies carried out in our country, interlinked Internet addiction and obesity are facing a serious public health problem [ 18]. In the last years, it has become more difficult to be healthy. New health problems are added to the old ones that we cannot move away from our life, like technology to the deterioration of the nature of nutrition and the environmental factors that negatively affect human health. In order to remain healthy, all we can do is pay attention to the negativity of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and to act accordingly. 2.3. Brain and gut reliability Hippocrates said “All diseases start in the intestine,” paying attention to the Hippocrates gut. The same question that has begun with Avicenna, Ibn Khaldun, and Hippocrates has been pushing us for centuries: do our guts rule us? The role of intestinal microbiota in health and disease is increasingly recognized. The micro -biota-intestinal-brain axis is a two-way path between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract. It is well known that intestinal microbiota affects the physiological, behavioral, and cognitive functions of the brain. Gut microbiota may include brain axis, intestinal microbiota and meta-bolic products thereof, enteric nervous system, sympathetic and parasympathetic branches within the autonomic nervous system, neural-immune system, neuroendocrine system, and central nervous system. In addition, there may be communication pathways between the intestinal microbiota and the brain, including the neural network of the intestine and brain, neuroendocrine-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, intestinal immune system, some neurotransmitters synthesized by intestinal bacteria, and barrier pathways including neural regulators and intestines. - eBook - ePub

A Comprehensive Overview of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Clinical and Basic Science Aspects

- Jakub Fichna(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

3: Irritable bowel syndrome and the brain-gut connection

Leon Pawlik; Aleksandra Tarasiuk Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz, PolandAbstract

The brain-gut axis (BGA) is a complex, bidirectional communication system between enteric nervous system and central nervous system and in healthy organism it is an essential pathway in regulating the proper functioning of the gastrointestinal tract. Main manifestations of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) such as abdominal pain, bloating and abnormal bowel movements can be understood as a disruption in BGA. Stress, strong emotional experiences or altered intestinal microbiota can affect BGA and therefore modulate the bowel motility, secretion and visceral sensibility. In this chapter we will discuss as well as describe constituents of the BGA and their connections with IBS.Keywords

Brain-gut axis; BGA; Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); Functional gastrointestinal disorder; Microbiota-gut-brain axisList of abbreviations5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine; serotoninACC anterior cingulate cortexACTH adrenocorticotropic hormoneANS autonomic nervous systemBGA brain-gut axisCNS central nervous systemCRH corticotrophin-releasing hormoneEC enterochromaffin cellsGABA gamma aminobutyric acidGI gastrointestinalGM gut microbiotaHPA hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (axis)IBS irritable bowel syndromeIBS-C constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndromeIBS-D diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeMC mast cellsMBGA microbiota-brain-gut axisSCFAs short chain fatty acidsVH visceral hypersensitivityIntroduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders and among the most frequent causes of gastroenterology consultations [1] . Despite the high prevalence (about 10% of the world population), the pathogenesis of IBS is still not fully understood. Main pathophysiological mechanisms are: altered GI motility, visceral hypersensitivity, increased intestinal permeability, brain-gut axis (BGA) dysregulation and changes in the intestinal microbiota. These changes in turn contribute to the main manifestations of IBS such as abdominal pain, bloating and abnormal bowel function (diarrhea and/or constipation) [2] . Psychosocial factors can also influence digestive function, symptom perception, illness behavior and outcome. Conversely, visceral pain affects central pain perception, mood and behavior. IBS may be perceived as a disorder resulting at least in part from disruption of BGA [3] . More recently, the role of the gut microbiota in the bidirectional communication along BGA, and subsequent changes in behavior, has emerged [4] - eBook - ePub

- A. Halaris, B. E. Leonard, A., Halaris, B.E., Leonard, Brian E. Leonard, Brian E., Leonard(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- S. Karger(Publisher)

Halaris A, Leonard BE (eds): Neuroprogression in Psychiatric Disorders.Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. Basel, Karger, 2017, vol 31, pp 152–161 (DOI: 10.1159/000470813) ______________________The Brain-Gut Axis Contributes to Neuroprogression in Stress-Related Disorders

Kieran Reaa · Timothy G. Dinana , b · John F. Cryana , ca APC Microbiome Institute and Departments of b Psychiatry and Neurobehavioural Science and c Anatomy and Neuroscience, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland______________________Abstract

There is a growing emphasis on the relationship between the complexity and diversity of the microorganisms that inhabit our gut (human gastrointestinal microbiota) and brain health. The microbiota-gut-brain axis is a dynamic matrix of tissues and organs including the brain, glands, gut, immune cells, and gastrointestinal microbiota that communicate in a complex multidirectional manner to maintain homeostasis. Changes in this environment may contribute to the neuroprogression of stress-related disorders by altering physiological processes including hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation, neurotransmitter systems, immune function, and inflammatory responses. While appropriate, coordinated physiological responses, such as immune or stress responses, are necessary for survival, the contribution of repeated or chronic exposure to stress may predispose individuals to a more vulnerable state leaving them more susceptible to stress-related disorders. In this chapter, the involvement of the gastrointestinal microbiota in stress- and immune-mediated modulation of neuroendocrine, immune, and neurotransmitter systems and the consequential behavior is considered. We also focus on the mechanisms by which commensal gut microbiota can regulate neuroinflammation and further aim to exploit our understanding of their role in the effects of the microbiota-gut-brain axis on the neuroprogression of stress-related disorders as a consequence of neuroinflammatory processes. - eBook - PDF

- Aise Seda Artis(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

rhamnosus in normal adult mice while avoiding the associated alterations in the expression of GABAAα2 mRNA in the amygdala; and vagotomy abolishes the ability of B. longum to attenuate anxiety induced by DSS colitis. 3. The second brain The relationship between the brain, the emotions, and the digestive tract is intense. So much so that many scientists refer to the intestine as the “second brain” or “gut-brain,” since the digestive tract contains a very complex neural network with a neuronal function very similar to the activity of the head. The presence of receptors to various neurotransmitters in the intestine has been demonstrated: it is known that some intestinal molecules, such as serotonin 5-HT, can modulate the patho -genic potential of Pseudomonas fluorescens by affecting its motility and pyoverdine production but without affecting its growth. It has been reported that gut microbiota can control the Figure 4. Key aspects of gastrointestinal physiology are controlled by the enteric nervous system, which is composed of neurons and glial cells. These cells of the enteric nervous system are connected to the central nervous system (in a bidirectional way). As an example, when we ingest food, through neural pathways and immune and endocrine mechanisms, we will perceive the sensation of satiety. Gut-Brain Axis: Role of Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease and Multiple Sclerosis http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79493 17 tryptophan metabolism of the host by enhancing the fraction of tryptophan available for the kynurenine route and decreasing the amount available for 5-HT synthesis [ 24 ]. Free fatty acid receptor 3 (FFAR3) receptors for short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) have been detected in sub -mucosal and myenteric ganglia, and the responsiveness of enteric neurons to glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids has been demonstrated [ 24 ]. - eBook - ePub

- Dilip Ghosh(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The brain-gut axis: a target for treating stress-related disorders .Mod. Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;28:90–99.24 . . Arentsen T, Raith H, Qian Y, Forssberg H, Diaz Heijtz R. Host microbiota modulates development of social preference in mice .Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:29719.25 . . Lee Y.K, Menezes J.S, Umesaki Y, Mazmanian S.K. Proinflammatory T-cell responses to gut microbiota promote experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis .Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl. 1):4615–4622.26 . . Agusti A, García-Pardo M.P, López-Almela I, Campillo I, et al. Interplay between the gut-brain Axis, obesity and cognitive function .Front Neurosci. 2018;12:155.27 . . Grenham S, Clarke G, Cryan J.F, Dinan T.G. Braingut- microbe communication in health and disease .Front Physiol. 2011;2:94.28 . . Browning K.N, Travagli R.A. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions .Comp Physiol. 2014;4:1339–1368.29 . . Foster J.A, Rinaman L, Cryan J.F. Stress & the gutbrain axis: regulation by the microbiome .Neurobiol Stress. 2017;7:124–136.30 . . Kihara N, Fujimura M, Yamamoto I, Itoh E, Inui A, Fujimiya M. Effects of central and peripheral urocortin on fed and fasted gastroduodenal motor activity in conscious rats .Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G406–G419.31 . . Czimmer J, Million M, Taché Y. Urocortin 2 acts centrally to delay gastric emptying through sympathetic pathways hile CRF and urocortin 1 inhibitory actions are vagal dependent in rats .Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G511–G518.32 . . Söderholm J.D, Yates D.A, Gareau M.G, Yang P.C, et al. Neonatal maternal separation predisposes adult rats to colonic barrier dysfunction in response to mild stress .Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G1257–G1263.33 . . Zheng G, Wu S.P, Hu Y, Smith D.E, Wiley J.W, Hong S. Corticosterone mediates stress-related increased intestinal permeability in a region-specific manner - eBook - PDF

- Helen M. Roche, Ian A. Macdonald, Annemie M. W. J. Schols, Susan A. Lanham-New(Authors)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Current studies, however, do not provide infor- mation about causality or underlying mecha- nisms, and future investigations should include large, randomised control trials and preclinical investigations to elucidate mechanisms. Importantly, the gut microbiota, which is made up of trillions of microorganisms living in the gastrointestinal system, are well-recognised mediators of the impact of diet and nutrition on gut–brain axis signalling (Cryan et al. 2019). For example, the gut microbiota are involved in the production of the neurotransmitter serotonin from dietary tryptophan, which plays important roles in regulating gut health, including motility. Moreover, microbiota-mediated conversion of tryptophan in the gut is also poised to have an impact on central levels of serotonin, which impact mood, behaviour and cognitive function. In this chapter, we will explore the connection between nutrition and the brain, discussing how key nutrients (e.g. glucose, amino acids, vita- mins and minerals) in the diet enter the brain. We will also discuss the importance of these nutrients for neurobiology, the role of nutrition in brain development, and how nutritional defi- ciencies may impact brain health. We will dis- cuss the emerging role of the gut microbiota in synthesis and availability of nutrients to the brain. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a deeper understanding of how nutrition can reach and impact the brain to optimise brain function and the key role of the gut microbiota in nutrient availability to the brain. 8.2 The gut microbiota in the nutrition–brain connection Humans and other animals share a mutualistic relationship with resident microorganisms that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract. The commu- nity has extensive metabolic capabilities which complement the activity of the liver and the gut mucosa and include functions essential for host digestion, yet we know that the role of the gut microbiota goes beyond digestion alone. - eBook - PDF

Integrative Therapies for Depression

Redefining Models for Assessment, Treatment and Prevention

- James M. Greenblatt, Kelly Brogan, James M. Greenblatt, Kelly Brogan(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

As with all bidirectional relationships, functional integrity of each system is required for optimal performance. A major part of this bidi-rectional system is the microbiota. MICROBIAL EFFECTS ON THE CNS The effects of microbial balance on CNS function begin early in life. The HPA axis is a neuroendo-crine system. It may be thought of as a system that is highly subject to changes in the environment and is highly programmable. It has been shown that HPA response is different in animals that are handled and cared for as neonates versus animals who experience maternal deprivation. Maternal deprivation causes exaggerated HPA response to stress, and this response exists throughout the life 24 Integrative Therapies for Depression of the animal. This altered HPA response is associated with the incidence of age-related neuropathol-ogy. It has been speculated that because of the bidirectional relationship early in life between neural and immune systems at a time when the CNS is particularly susceptible to environmental influences, microbial colonization and subsequent effects on the immune system might alter the development of HPA responsiveness. This has been demonstrated in animals, with genetically engineered germ-free mice displaying exaggerated HPA response to mild stress. This response can be corrected by colo-nization from pathogen-free controls in the experiment. Additionally, it was shown that colonizing the germ-free mice with enteropathogenic E. coli could actually increase the stress response. This suggests that not only is the presence of commensal bacteria critical, but the absence of pathogens may be as well. Another important finding from the study was a reduction of brain-derived neuro-trophic factor (BDNF) and reduced protein levels in the cortex and hippocampus of germ-free mice compared to pathogen-free mice. This is an important factor because BDNF is involved in many regulatory processes in the brain, including mood and cognition. - eBook - ePub

- Nicholas W. Gilpin(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Dysbiosis-induced changes in metabolite production, intestinal permeability, immune regulation, and neuronal signaling are all theorized to play a role in behavioral changes and disease pathology (Fig. 12.3). Given the influence many psychoactive drugs have on feeding behavior and metabolism, it is no surprise there is a growing literature associating changes in the gut microbiome to chronic substance misuse (Meckel and Kiraly, 2019). Perhaps by elucidating the precise mechanisms involved and further defining the bidirectional crosstalk between the gut and brain, new therapeutic targets can be identified for the treatment of substance use disorders and their sequalae. Figure 12.3 There is a growing body of work indicating interactions between the host, the brain, and the gut microbiome, facilitated by the following. (1) Increased gut permeability enables either microbes or microbial metabolites to enter the bloodstream. (2) Gut microbes produce neuromodulatory metabolites (e.g., short chain fatty acids), as well as induce the production of host-derived vitamins (B12), neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin), and hormones (e.g., peptide YY) that may impact neurological and host health. (3) Bidirectional interactions may occur directly via innervation of the vagus nerve, providing a direct line of communication between the enteric and central nervous system. (4) In addition, gut–brain interactions can occur through immune-mediated inflammatory pathways, such as (A) microbial-driven systemic inflammation linked to the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, and (B) stressors that can alter the gut via inflammatory pathways. (5) Finally, gut microbes can metabolize xenobiotics, impacting brain function. Reprinted from Tremlett, H., Bauer, K.C., Appel-Cresswell, S., Finlay, B.B., Waubant, E., 2017. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: a review. Ann. Neurol. 81, 369–382

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.