Chemistry

Electrophile and Nucleophile

Electrophiles are electron-deficient species that seek to accept a pair of electrons, typically through a reaction with a nucleophile. Nucleophiles, on the other hand, are electron-rich species that donate a pair of electrons to form a new chemical bond with an electrophile. In chemical reactions, electrophiles and nucleophiles play crucial roles in determining the direction and outcome of the reaction.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

4 Key excerpts on "Electrophile and Nucleophile"

- eBook - PDF

Chemical Reactivity Theory

A Density Functional View

- Pratim Kumar Chattaraj(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Most electrophiles are positively charged, having an atom which carries a partial positive charge, or does not have an octet of electrons. Qualitatively, as Lewis acidity is measured by relative equilibrium constants, electrophilicity is measured by relative rate constants for reactions of different electrophilic reagents toward a common substrate (usually involving attack at a carbon atom). Closely related to electrophi-licity is the concept of nucleophilicity, which is the property of being nucleophilic, the relative reactivity of a nucleophile. A nucleophile is a reagent that forms a chemical bond to its reaction partner (an electrophile) by donating bonding electrons. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are by de fi nition Lewis bases. All molecules or ions with a free pair of electrons can act as nucleophiles, although anions are more potent than neutral reagents. It is generally believed that it was Ingold [1] in the early 1930s who proposed the fi rst global electrophilicity scale to describe electron-de fi cient (electrophile) and electron-rich (nucleophile) species based on the valence electron theory of Lewis. Much has been accomplished since then. One of the widely used electrophilicity scales derived from experimental data was proposed by Mayr et al. [5 – 12]: 179 log k ¼ s ( E þ N ) , ( 13 : 1 ) where k is the equilibrium constant involving the Electrophile and Nucleophile E and N are, respectively, the electrophilicity and nucleophilicity parameters s is a nucleophile-speci fi c constant The second well-known electrophilicity or nucleophilicity scale was by Legon and Millen [13,14]. In this scale, the assigned intrinsic nucleophilicity is derived from the intermolecular stretching force constant k , recorded from the rotational and infrared (IR) spectra of the dimer B . . . HX formed by the nucleophile B and a series of HX species (for X halogens) and other neutral electrophiles. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

139 140 Electrophilicity index in organic chemistry 1. Introduction The understanding of the course of organic chemical reactions was stimulated with the development of the valence electronic Lewis’ theory 1 and the general acid–base theory of Lowry and Brönsted. 2 On the basis of these electronic models, Ingold 3 in the 1930s introduced the concepts of Electrophile and Nucleophile for atoms and molecules. These terms are associated with electron-deficient and electron-rich species, respectively. From that time, there have been several attempts to classify organic molecules within empirical (hopefully absolute) scales of electrophilicity and nucleophilicity. However, this objec-tive is difficult to reach if one considers that a universal electrophilicity/nucleophilicity model should accommodate, within a unique scale, substrates presenting a large diversity in electronic and bonding properties, without mentioning the presence of the medium. Recent works of Mayr and co-workers 4 − 14 have illustrated this trend. In fact, these authors have established, in contrast to the accepted opinion about the relative character of the experimental electrophilicity/nucleophilicity scales for many reactions in organic and organometallic chemistry, that it would be possible to define nucleophilicity and electrophilicity parameters that are independent of the reaction partners. Mayr et al. proposed that the rates of reactions of carbocations with uncharged nucleophiles obey the linear free energy relationship given by: 4 − 14 log k = s E + N (1) where E and N are the electrophilicity and nucleophilicity parameters, respectively, and s is the nucleophile-specific slope parameter. These authors observed that in general the solvent effects on the reaction rates with nucleophiles and hydride donors were small and could be neglected to a first approximation. 11 For the determination of the strengths of electrophiles, Mayr et al. - eBook - ePub

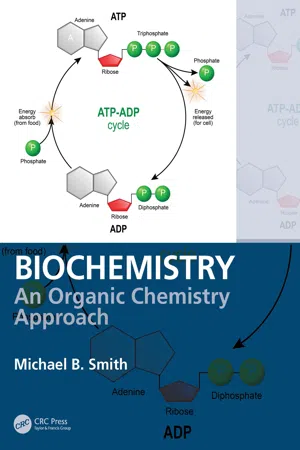

Biochemistry

An Organic Chemistry Approach

- Michael B. Smith(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

3 Nucleophiles and ElectrophilesAliphatic substitution reactions are early examples of organic chemical reactions in a typical undergraduate organic chemistry course. Such reactions involve the reaction of nucleophilic species with an electrophilic species, and for the most part they follow first-order or second-order kinetics. There are nucleophiles that are prevalent in biochemical reactions, including alcohols, amines, and thiols. Substitution reactions in a typical organic chemistry course involve reactions at carbon that is connected to a heteroatom moiety such as a halogen leaving group. In biochemistry the leaving group is often a phosphonate ester or another biocompatible group. Another type of nucleophilic reaction involves carbonyl compounds, including acyl addition of ketone and aldehyde moieties and acyl substitution reactions of carboxylic acid derivatives.This chapter will briefly review the SN 2 and SN 1 reactions and then describe nucleophiles that are common in biochemical applications and the substitution reactions that are common for these nucleophiles. Nucleophilic reactions require electrophilic species. Electrophiles or electrophilic substrates are common in biochemistry, including phosphonate derivatives, carbonyl compounds and imine compounds. Any discussion of typical nucleophilic reactions also requires an understanding of such electrophilic substrates. The fundamentals of both acyl addition and of acyl substitution reactions will be presented for carbonyl electrophilic centers and the reactions of these electrophilic centers with nucleophiles.3.1 Nucleophiles and Bimolecular Substitution (the SN 2 Reaction)The SN 2 reaction is one of the seminal reactions in a typical undergraduate organic chemistry course. The reaction of 1-bromo-3-methylbutane with sodium iodide (NaI) using acetone as a solvent gave 1-iodo-3-methylbutane, in 66% yield.1 In terms of the structural changes, the iodide ion substitutes for the bromine, producing bromide ion (Br– ). Iodide reacted as a nucleophile in the reaction at Cδ+ of the alkyl bromide, breaking the C—Br bond and transferring the electrons in that bond to bromine. In molecules that contain the C—Br bond, or indeed a C—C bond, where X is a heteroatom-containing group, the carbon will have a δ+ dipole. In other words, the carbon atom is electrophilic, and the substrate that reacts with the nucleophile is called an electrophile. The reaction of a nucleophile with an aliphatic electrophile is formally called nucleophilic aliphatic substitution , illustrated in Figure 3.1 . The displaced atom or group (e.g., chloride), departs (leaves) to become an independent ion. Displacement of chlorine leads to the chloride ion (Cl– ), but the bromide ion, iodide ion, or a sulfonate anion also correlates to X, which is referred to as a leaving group . In many biochemical reactions, the leaving group is a phosphate, —O–PO2 - eBook - ePub

- Edwin Vedejs, Scott E. Denmark, Edwin Vedejs, Scott E. Denmark(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley-VCH(Publisher)

* interactions will be covered.4.2 Nucleophilicity

4.2.1 The Swain–Scott and Edwards Approaches

The development of concepts aiming at understanding reactivity in organic chemistry can be traced back to the late 1920s, when Ingold introduced the terms “electrophile” and “nucleophile” for reactive organic species, characterized by a lack or surplus of electrons, respectively [1]. Since then, many efforts have been made to quantify the electrophilicity and the nucleophilicity of organic compounds. In this context, attempts have been made to build reliable scales of reactivity.In 1953, Swain and Scott proposed the linear free energy relationship depicted in Eq. (4.1) and applicable to SN 2 reactions. In this equation, k is the bimolecular rate constant for a given electrophile reacting with a given nucleophile, k0 is the rate constant of the reaction of the electrophile with water, s characterizes the sensitivity of an electrophile to variations in the nucleophile, while n characterizes the nucleophilicity of a nucleophile. Methyl bromide was chosen initially as a reference electrophilic substrate (s = 1.00) and water was taken as the standard nucleophile (n = 0) [2].(4.1)One year later, Edwards proposed a four-parameter linear free energy relationship, based on the assumption that the nucleophilicity depends on the basicity and the polarizability of the nucleophile (Eq. (4.2) ) [3].(4.2)In this equation, P and H denote the polarizability and basicity of nucleophiles, respectively, while A and B are substrate parameters representing the sensitivity of the reactions to changes in these two quantities, that is, polarizability and basicity, respectively. The parameter H is derived from pKa values (H = pKa + 1.74) and the parameter P is determined from refraction measurements (P = log (R∞ /RH2O )), where R∞ and RH2O are the molar refractions of the reagent and of water.In some instances, the application of Eq. (4.2) was found to give better fits than the Swain–Scott analog but an extensive use of this correlation was precluded because of the difficulty in determining reliable Edwards parameters. Thus, keeping with the Swain–Scott correlation, Pearson et al. could determine the nucleophilicity parameters for various nucleophiles using methyl iodide as a reference electrophile (nMeI ) and methanol as a standard nucleophile [4]. Values of the nMeI parameter for a variety of nucleophiles are given in Table 4.1 . Interestingly, Pearson et al. found that Eq. (4.1)

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.