Chemistry

Reactions of Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Reactions of aromatic hydrocarbons involve various chemical transformations of compounds containing benzene rings. These reactions can include electrophilic aromatic substitution, where an electrophile replaces a hydrogen atom on the benzene ring, and nucleophilic aromatic substitution, where a nucleophile replaces a substituent on the benzene ring. These reactions are important in the synthesis of many organic compounds.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Reactions of Aromatic Hydrocarbons"

- Herman Pines(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

5 Reactions of Aromatic Hydrocarbons with Olefins 5 . 1 I N T R O D U C T I O N The acid-catalyzed Reactions of Aromatic Hydrocarbons with olefins re-sult almost exclusively in addition of alkyl groups to the aromatic ring [1 (1964, Patinkin and Friedman)]. The base-catalyzed reactions of al-kylaromatics with olefins are unique in that they allow one to enlarge the alkyl groups of an arylalkane, and thus they become an effective tool for the preparation of hydrocarbons by a simple, one-step synthesis. The more important aspects of this reaction have been reviewed [2 (1960, Pines and Schaap), 3 (1966, Eberhardt), 4 (1974, Pines), 5 (1974, Pines)]. Arylalkanes suitable for this reaction are those which contain a benzylic hydrogen. The olefins used for this reaction are ethylene, propene, and, to a smaller extent, butènes. Conjugated dienes yield alkenylaromatic com-pounds, whereas styrene and its derivatives, such as α-methyl- and /3-alkylstyrenes, produce aralkylaromatic hydrocarbons. The reaction can be presented by the general formulas given in Eqs. (1) and (2). R R Ro. A r -C H + C H 2 = C • A r — C -C -C H , (1) I Rs I I 3 Ri Ri R3 R R I Ar I Η Ar Ar—CH + C H = C ' A r -C — C H — C ' I I R3 I I R3 ί Λ R x Ri R! Ra (2) Ar = aryl R i -R s = Η or alkyl Catalysts and reaction conditions depend greatly on the aromatics and olefins used in the reaction. Sodium and potassium are the most effective catalysts for the side-chain alkylation of alkylaromatic hydrocarbons. A 240 5.1 Introduction 241 sodium catalyst usually requires the presence of small amounts of or-ganosodium compounds or the presence of ^promoters, chain precur-sors which can react with sodium to form organosodium compounds. The most frequently used promoters are anthracene and o-chlorotoluene. Sodium hydride, benzylsodium, and supported alkali metals, such as potassium on graphite, are also used as catalysts for this reaction.- eBook - ePub

- James G. Speight(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Aromatic compounds are characterized by having a stable ring structure due to the overlap of the π-orbitals (resonance). Accordingly, they do not easily add to reagents such as halogens and acids as do alkenes. Aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives are susceptible, however, to electrophilic substitution reactions in presence of a catalyst. Aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives are generally nonpolar. They are not soluble in water, but they dissolve in organic solvents such as hexane, diethyl ether, and carbon tetrachloride.In the traditional chemical industry, aromatic derivatives such as benzene, toluene, and the xylene were made from coal during the course of carbonization in the production of coke and town gas. A much larger volume of these chemicals are now made as refinery byproducts. A further source of supply is the aromatic-rich liquid fraction produced in the cracking of naphtha or low-boiling gas oils during the manufacture of ethylene and other olefin derivatives.Aromatic compounds are valuable starting materials for a variety of chemical products. Reforming processes have made benzene, toluene, xylene, and ethylbenzene economically available from petroleum sources.In the catalytic reforming process, a mixture of hydrocarbon derivatives with boiling points between 60°C and 200°C (140°F–390°F) is blended with hydrogen and then exposed to a bifunctional platinum chloride or a rhenium chloride catalyst at 500°C–525°C (930°F–975°F) and pressures ranging from 120 to 750 psi. Under these conditions, aliphatic hydrocarbon derivatives form rings and lose hydrogen to become aromatic hydrocarbons. The aromatic products of the reaction are then separated from the reaction mixture (the reformate) by extraction using a solvent such as diethylene glycol (HOCH2 CH2 OH) or sulfolane:The benzene is then separated from the other aromatic derivatives by distillation. The extraction step of aromatics from the reformate is designed to produce a mixture of aromatic derivatives with lowest nonaromatic components. Recovery of the aromatic derivatives commonly referred to as benzene, toluene and xylene isomers, involves such extraction and distillation steps. - eBook - PDF

- Allan Blackman, Steven E. Bottle, Siegbert Schmid, Mauro Mocerino, Uta Wille(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

As it is now used, the term aromatic refers instead to the fact that benzene and its derivatives are highly unsaturated compounds that are stable towards reagents that react with alkenes. CHAPTER 16 The chemistry of carbon 843 We use the term ‘arene’ to describe aromatic hydrocarbons, by analogy with alkane and alkene. Benzene is the parent arene. Just as we call a group derived by the removal of an H from an alkane an alkyl group and give it the symbol R (see the chapter on the language of chemistry), we call a group derived by the removal of an H from an arene an aryl group and give it the symbol Ar. The structure of benzene Let us imagine ourselves in the mid-nineteenth century and examine the evidence on which chemists built a model for the structure of benzene. First, because the molecular formula of benzene is C 6 H 6 , it seemed clear that the molecule must be highly unsaturated. Yet benzene does not show the chemical properties of alkenes, the only unsaturated hydrocarbons known at that time. Benzene does undergo chemical reactions, but its characteristic reaction is substitution rather than addition. When benzene is treated with bromine in the presence of iron(III) chloride as a catalyst, for example, only one compound, with molecular formula C 6 H 5 Br, forms. C 6 H 6 benzene + Br 2 FeCl 3 ← → C 6 H 5 Br bromobenzene + HBr Chemists concluded, therefore, that all six carbon atoms and all six hydrogen atoms of benzene must be equivalent. When bromobenzene is treated with bromine in the presence of iron(III) chloride, three isomeric dibromobenzenes are formed. C 6 H 5 Br bromobenzene + Br 2 FeCl 3 ← → C 6 H 4 Br 2 dibromobenzene (formed as a mixture of three constitutional isomers) + HBr For chemists in the mid-nineteenth century, the problem was to incorporate these observations, along with the accepted tetravalence of carbon, into a structural formula for benzene. - eBook - PDF

Chemical Reactivity Theory

A Density Functional View

- Pratim Kumar Chattaraj(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Thus, benzene reacts through electrophilic aromatic substitutions rather than additions [3]. However, this kind of reactivity behavior traditionally related to aromatic compounds has many important exceptions. For instance, phenanthrene and anthracene add bromine like ole fi ns [3,22], the reaction rate being faster for anthracene than phenanthrene [23]. And 3-D aromatic compounds such as fullerenes (e.g., C 60 or C 70 ) have a rich and extensive addition chemistry but no substitution reactions at all [24,25]. Thus, it is clear that the reactivity of aromatic species is relatively complex and, for this reason, to our knowledge, no index of aromaticity has been de fi ned based on chemical reactivity properties. Aromaticity and reactivity are two deeply connected concepts, although their relationship is complex. Obviously, not all reactions are affected by aromaticity (e.g., S N 2, E2 . . .), but taking into account that among the approximately 20 million compounds known, two-thirds are fully or partially aromatic [26], it is clear that many chemical reactions will be in fl uenced by the increase or decrease in aromaticity all over the reaction. The most important group of this kind of reactions are the pericyclic ones, which were categorized by Woodward and Hoffmann into fi ve groups: sigmatropic shifts, cycloaddition, electrocyclic, cheletropic, and group trans-fer reactions [27,28]. Chemical structures (reactants, intermediates, and products) and transition states (TSs) are often in fl uenced by aromatic stabilization or antiaro-matic destabilization. For an elementary reaction, it may happen that all chemical structures and TSs or just one or two of them are aromatic or antiaromatic. In pericyclic reactions, it is found that most thermally allowed reactions take place through aromatic TSs, while TSs of thermally forbidden reactions are usually less aromatic or antiaromatic (vide infra). - eBook - PDF

- C W Bird, G W H Cheeseman(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Royal Society of Chemistry(Publisher)

Contents xi 2 Aromatic Substitution by Carbenes [ntermolecular Reactions Cyclizations 3 Aromatic Substitution by Nitrenes Intermolecular Reactions Cyclizations Chapter 9 Addition Reactions By G. V. Boyd 310 310 31 1 312 312 313 317 1 Introduction 317 2 Reduction 317 3 Oxygenation 320 4 Other Addition Reactions Carbocyclic Compounds Heterocyclic Compounds 5 Cycloaddition Reactions Carbocyclic Compounds Benzene and Derivatives Naphthalenes and [ 1 IIAnnulenylidene Anthracene and its Derivatives Phenanthrenes Biphenylene and Higher Condensed Benzenoid Hydrocarbons ortho-Quinones, ortho-Quinone Imines, and ortho- para-Quinones and their Analogues Cyclopropenones and Cyclopropenethiones Compounds with Five-membered Rings : Fulvenes and Compounds containing Seven-membered Rings Furans Thiophens Indole and Isoindoles Other Compounds containing Five-membered Rings Monoazines Uracil and Thymine Other Diazines Other Compounds containing Six-membered Rings Thioquinone Methides C yclopentadienones Heterocyclic Compounds 322 322 324 327 327 327 330 33 1 332 333 333 335 338 339 34 1 344 344 349 350 351 352 355 357 358 xii Aromatic and Heteroaromatic Chemistry Chapter 1 0 Ring-cleavage Reactions By T. - J. Grimshaw(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

CHAPTER 7REDUCTION OF AROMATIC RINGS

Aromatic Compounds - Radical-Anions

With stringent precautions to avoid the presence of water, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons show two one-electron reversible waves on cyclic voltammetry in dimethylformamide (Table 7.1 ). These are due to sequential one-electron additions to the lowest unoccupied molecular π-orbital [1 ]. Hydrocarbons with a single benzene ring are reduced at very negative potentials outside the accessible range in this solvent. Radical-anions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [2 ] and also alkyl benzenes [3 ] were first obtained by the action of alkali metals on a solution of the hydrocarbon in tetrahydro furan. They have been well characterised by esr spectroscopy. The radical-anions form coloured solutions with absorption bands at longer wavelength than the parent hydrocarbon [4 ,5 ].TABLE 7.1Reduction potentials for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rigorously dried dimethylformamide, tetrabutylammonium bromide, determined by cyclic voltammetry. Ref. [1] .Substrate First electron addition E° / V vs. sce Second electron addition E° / V vs. sce Anthracene −1.915 −2.655 9,10-Dipheny lanthracene −1.830 −2.505 Chrysene −2.225 −2.730 Coronene −2.030 −2.255 Perylene −1.640 −2.255 Protonation by residual water in the solvent is the rate-determining step in the decay of most aromatic anion-radicals. Hydrogen ions and also general acids are effective protonating agents. In only a very few cases has dimerization of the radical-anion been found to be faster than protonation. The dimerization step has been followed by electrochemical techniques for 1,3-dicyanobenzene radical-anion where the rate constant is 2.4 × 105 M−1 s−1 [6 ]. Methyl anthracene-9-carboxylate radical-anion reversibly dimerises through the 10-position [7- eBook - ePub

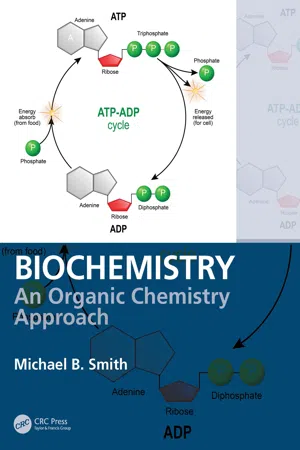

Biochemistry

An Organic Chemistry Approach

- Michael B. Smith(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

9 Aromatic Compounds and Heterocyclic CompoundsBenzene is a special type of hydrocarbon. Derivatives are known by replacing the hydrogen atoms of benzene with substituents and/or functional groups. There are hydrocarbons related to benzene that have two, three, or more rings fused together (polycyclic compounds). The unifying concept of all these molecules is that they are aromatic, which means that they are especially stable with respect to their bonding and structure.9.1 Benzene and Aromaticity

Benzene is a hydrocarbon with the formula C6 H6 . It is the parent of a large class of compounds known as aromatic hydrocarbons. The structure and chemical reactivity of aromatic hydrocarbons are so unique that benzene derivatives are given their own nomenclature system. This discussion will begin with the unique structure of benzene.The structure of benzene is shown in Figure 9.1 . It is known that the C—C bond length in ethane is 1.53 Å (153 pm), and the C—C bond length is 1.536 Å (153.6 pm) in cyclohexane. The bond distance for the C=C bond in ethene is 1.34 Å (134 pm). These data indicate that a C=C unit has a shorter bond distance than a C—C unit. If benzene has a structure with both single and double bonds, it should have three longer C—C single bonds and three shorter C=C units. It would then be called cyclohexatriene. It has been experimentally determined that all six carbon–carbon bonds have a measured bond distance of 1.397 Å (139.7 pm), a value that lies in between those for the C–C bond in an alkane and the C=C unit of an alkene. This observation means that the C–C bonds in benzene are not single bonds, nor are they C=C double bonds where the π-electrons are localized between two carbons in a π-bond. This molecule is not cyclohexatriene, it is benzene . Each carbon in benzene is sp2 hybridized, however, which means each has a trigonal planar geometry. The planar geometry is seen more clearly in the molecular model of benzene in Figure 9.1

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.