Chemistry

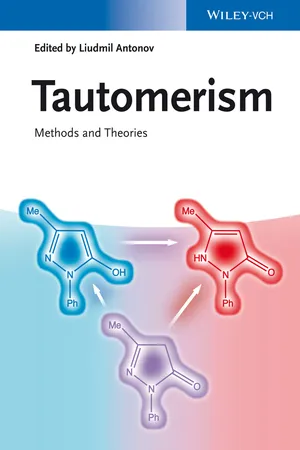

Tautomerism

Tautomerism is a chemical phenomenon where a molecule can exist in two or more forms that differ in the position of a proton or a double bond. These forms are called tautomers and can interconvert rapidly. Tautomerism is important in biochemistry and organic chemistry.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

3 Key excerpts on "Tautomerism"

- eBook - ePub

- Marc Descamps(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley-VCH(Publisher)

Chapter 7 Tautomerism in Drug DeliveryZaneta Wojnarowska and Marian PaluchAccording to common knowledge, Tautomerism is observed when one chemical compound is represented by two or more molecular structures that are related by an intramolecular movement of hydrogen between different polar atoms and the rearrangement of double bonds [1]. The most commonly observed examples of this phenomenon are reversible transformations between ketone and enol, amide and imidic acid, lactam and lactim, or enamine and imine forms. On the other hand, the tautomeric reactions in which the heterocyclic ring is opened and closed is usually called ring–chain Tautomerism or mutarotation in the case of carbohydrates chemistry.Tautomerization attracts the attention of scientists from many disciplines, including physics, organic and biochemistry, and pharmaceutical science. It is of great importance especially in drug industry because there are a number of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), biopharmaceuticals, and chemical excipients (e.g., saccharides) that readily convert into other isomers when their crystalline structure is lost. According to the literature data, 26% of commercially available APIs reveal the ability to exist in more than one chemical form (Figure 7.1 ) [2].Adapted from Martin [2]. Reproduced with permission of Springer.Frequency distribution of tautomers of a marketed drug.Figure 7.1 - eBook - ePub

Tautomerism

Methods and Theories

- Liudmil Antonov(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Wiley-VCH(Publisher)

8 and was defined as “one of the most difficult subjects of experimental science.”It is worth remarking here that the pioneers of Tautomerism were not armed with some extraordinary equipment. They had to trust mainly their eyes and their abilities to reach conclusions based on a limited amount of experimental information, which, actually, was enough for them to correctly define the factors influencing Tautomerism in solution: the chemical structure (main tautomeric skeleton and substituents) and the environment (solvents, temperature, acidity, salt additions).The problem is that each of these factors brings two questions: how and to what extent the tautomeric equilibrium is affected. The first question is qualitative; it brings as answer a descriptive explanation of the effects or a relative description, comparing to other compounds. Such a study can be done (and it was in the beginning) even without equipment by looking for visual changes (color change, precipitation, etc.). In terms of molecular spectroscopy methods, which are traditionally used for stationary state study of tautomeric systems (UV–vis absorption, fluorescence, IR, NMR), it means change in the registered instrumental signal.The second question is quantitative. Its answer requires the values of the equilibrium constants (and related parameters) to be estimated in the terms of analytical chemistry. Following this, the concept for quantitative instrumental analysis postulates that the individual responses of the components of a mixture must be previously measured, that is, be known. However, taking into account that even if the individual tautomers are isolated in the solid state, in solution they always convert to a mixture, and such a requirement cannot be easily fulfilled. This contradiction has left a mark on the studies of tautomeric systems even today. Many compounds have been studied, but the conclusions are approximate and do not allow exact treatment of environmental effects and structure–tautomeric property relations. Of course, there have been attempts to mimic instrumental responses of individual tautomers by using model fixed compounds, where the movable proton is replaced by a methyl group, or by using compounds whose structure approximates the structure of the tautomers under investigation. As described in Chapters 2, 5, and 12, these approaches work reasonably well in some limited cases, but they always remain semiquantitative, because there is no physical ground for full correspondence between instrumental signals (as both the shape and intensity) of the model and of real tautomers. - eBook - ePub

Carbohydrate Chemistry

Fundamentals and Applications

- Raimo Alén(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

Fig. 3.1. The main types of isomerism and their subtypes.The branch of organic chemistry that examines the three-dimensional structures of molecules,stereochemistry, has gained importance when striving to understand the physical and chemical properties of various compounds. In carbohydrate chemistry, it is also essential to know the stereochemical structure of the compounds. Stereoisomerism can be seen to generally represent the form of isomerism where compounds with the same chemical structure (i.e., the order of attachment of the atoms involved and the location of the bonds between them) differ from each other only in the spatial direction of their atoms or atom groups. This isomerism is divided into (i)optical isomerism(“physical isomerism”), (ii)conformational isomerism, and (iii)geometric isomerism(“cis/transisomerism”). As the first two types are characteristic of carbohydrates, they will be emphasized in the following discussion.3.2.Constitutional Isomerism

Constitutional isomers generally differ from one another only in the order of attachment of their atoms and the location of their bonds. In the functional group isomerism, the isomers have the same molecular formula, but their functional groups are different. The following compounds are examples of such isomers:Chain isomers have the same molecular formula, but the skeleton (usually carbon skeleton) differs by having branches or otherwise. The following compounds (C5 H12 ) are examples:The number of chain isomers increases very rapidly with the increase in the number of carbon atoms in the compound. Theoretically, for 6, 7, 8, 15, and 20 carbon atoms in an aliphatic hydrocarbon, the numbers of possible chain isomers are 5, 9, 18, 4347, and 366,319, respectively.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.