Economics

Utility Theory

Utility theory is a concept in economics that measures the satisfaction or happiness a consumer derives from consuming a good or service. It is based on the idea that individuals make choices to maximize their utility, or well-being, given their preferences and constraints. Utility theory is used to analyze consumer behavior and make predictions about their choices.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Utility Theory"

- eBook - ePub

The Economics of Resource Allocation in Health Care

Cost-utility, social value, and fairness

- Andrea Klonschinski(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In summary, the basic ingredients of Jevons’ economics are Bentham’s utilitarianism, psychophysiology, and the use of the differential calculus. Jevons strictly rejected the labor theory of value and made the individuals’ feelings of pleasures and pains the building blocks of his theory. Psychophysiology’s mechanistic conception of the human mind allowed him to apply the methods of the natural sciences and, in particular, mathematics to the investigation of individual decision making as a calculus of pleasure and pain. The application of the calculus, in turn, permitted Jevons to focus on marginal changes in the amounts of utility or, what comes to the same thing in a psychophysiological framework, on the marginal units of pleasure the individual economic agent derives from commodities. These changes are not proportional to the increase in the amount of a commodity but are in fact decreasing. This principle of diminishing marginal utility enabled Jevons to derive the equimarginal principle according to which the individual allocates his resources so as to maximize his own pleasure or, as it were, utility. Methodologically, the economic theory of utility-maximizing behavior can hence be considered the “child of the marriage of utility with the technique of marginal increments and decrements, which itself led directly to the consideration of extremal problems” (Dobb 1973: 172).As to the adoption of the Benthamite utility concept it deserves emphasis again that while Bentham’s Principles first and foremost addressed the legislator who should build institutions to the advantage of all, Jevons’ individualistic account of utility maximization was totally detached from any societal concerns. Here, the utility concept serves an explanatory function within demand theory. To accomplish that task, it referred to “subjective scales of valuation which were supposed to reside in the consumer’s mind” (Endres 1999: 602). Thereby, pleasure or utility are considered as being quantities that provide “agents with a monotonic criterion by which to carry out the ordering of the alternative outcomes they face” (Warke 2000a: 20). Put differently, utility provided for an ordering principle, explaining how subjects generate their preference rankings (see Mandler 2001: 374). The maximization of pleasure, then, was regarded as the subjects’ aim and motive for action. Henceforth, utility maximization in economics became more and more associated with the idea of individual rationality (see Cudd 1993: 106) and the problem an economic agent faces became framed as the problem of allocating his resources “in such a way that his well-being is enhanced to the greatest degree possible” (Colvin 1985: 9). The publication of TPE can thus be conceived as the hour of birth of the economic man, i.e., of the “discrete, self-contained, self-interested” individual of modern microeconomics (Colvin 1985: 5), aiming at the maximization of pleasure (see Little 1957: 10). Put differently, the TPE gave rise to the fundamental principle of modern economics that “economic behaviour is maximising behaviour subject to constraints” (Blaug 1997: 280).42 - eBook - PDF

Microeconomics

A Global Text

- Judy Whitehead(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 Theory of the Consumer Cardinal Utility Theory; Ordinal Utility Theory and Revealed Preference Theory; Utility and the Demand Function; The Demand Curve and The Law of Demand; The Engel Curve. The study of the economic behaviour of the individual consumer is a prequel to the study of demand for goods and services in the product (commodities) market. This is Utility Theory which goes back to first principles. The theories provide the foundation for the law of demand, indicating how and why consumers respond in particular ways to the structure of incentives and various other factors (prices, income, tastes) in the market. An understanding of consumer behaviour and how consumers optimize within budget constraints is useful, particularly to sellers in their quest for market advantage and greater competitiveness. 2.1 THE INDIVIDUAL CONSUMER AND UTILITY MAXIMIZATION Consumer theory has its genesis in the theory of utility maximization. The concept of utility or satisfaction is central to the study of the consumer behaviour in the market. This refers to the satisfaction individuals derive from the consumption of goods and services. The standard theory of the consumer follows the traditional deductive approach using the scientific method of inquiry. This approach proceeds in a structured way from assumptions, through the body of the theory to its testable conclusions. The traditional analysis of the consumer is done under certainty. The consumer is always assumed to be rational and to optimize with respect to the given values for income and market price. Consumers are assumed to have full knowledge of the available commodities and their prices in the market, and to know their income limit. Consumers plan to spend their income to attain the highest possible satisfaction (utility) within these parameters. In general, there are considered to be two major approaches to the theory of utility maximization: The Cardinal theory and the Ordinal theory. - eBook - PDF

Predicting Human Decision-Making

From Prediction to Action

- Ariel Rosenfeld, Sarit Kraus, Ariel Geib, Sarit Yang(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Springer(Publisher)

7 C H A P T E R 2 Utility Maximization Paradigm That’s your game theory? Rock Paper Scissors with statistics? Peter Watts, Blindsight The study of decision-making, human or automated, is an interdisciplinary effort, studied by mathematicians, computer scientists, economists, statisticians, psychologists, biologists, politi- cal and social scientists, philosophers and others [138, Chapter 1.2]. Decision-making is cen- tered around a decision-maker, an agent, human, or otherwise (e.g., automated), who selects a choice from available options. A decision-maker will be called intelligent if there is an underlying reasoning mechanism for its choices. Economists typically assume that an agent’s behavior is motivated primarily by material incentives, and that decisions are governed mainly by self-interest and rationality. In this context, rationality means that decision-makers use all available information in a logical and systematic way, so as to make the best choices they can given the alternatives at hand and the objective to be reached [171]. Utility Theory provides a well-established starting point for modeling and analyzing de- cisions. It also implies that decisions are made in a forward-looking way, by fully taking into account future consequences of current decisions. In other words, so-called extrinsic incentives are assumed to shape economic behavior. Utility is a measure representing the satisfaction ex- perienced by an agent from a service, good or state. Though a utility cannot always be directly measured (how satisfied am I from a slice of pizza?), it is reasonable to assume that a rational agent would want to maximize its obtained utility. It turns out that the notion of utility is a very powerful tool for representing and analyzing an agent’s decision-making. We will differ between two environmental settings: single decision- maker and multiple decision-makers. - eBook - PDF

- James D. Morrow(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

After this initial observation, Utility Theory lay dormant until Jeremy Bentham advanced utilitarianism as a philosophy in the 1800s. Bentham's Utility Theory was, mathematically speak-ing, quite sloppy and is not useful for developing a rigorous theory of decision. Consequently, utility was rejected as a useful concept until the middle of the twentieth century. Von Neumann and Morgenstern revived Utility Theory by providing a firm mathematical foundation for the concept in an appendix to their Theory of Games and Economic Behavior ([1943] 1953). Several rigorous versions of Utility Theory were produced after the publication of that book. Since then, economists have reformulated economic theory using Utility Theory and game theory as the description of individual behavior. This chapter begins with the concept of rationality. The characteristics of rational preferences are presented, followed by a discussion of some common misconceptions about rationality. The elements of a formal decision problem are described, and the idea of expected utility is introduced. Two examples, Utility Theory 1 7 one frivolous and one historical, illustrate these ideas. I then present the for-mal basis of Utility Theory, the Expected Utility Theorem. That theorem shows that a utility function can be found to represent preferences over actions when those preferences observe six conditions. Some common misconceptions about Utility Theory are rebutted. I next consider how utility functions represent dif-ferent reactions to risk and preferences over time. I apply Utility Theory in two simple examples, one concerning deterrence and the other concerning when people should vote. I end the chapter with a discussion of the limitations of Utility Theory. The Concept of Rationality Game theory assumes rational behavior. But what is meant by rationality? In everyday parlance, rational behavior can mean anything from reasonable, thoughtful, or reflective behavior to wise, just, or sane actions. - eBook - PDF

Capital, Profits, and Prices

An Essay in the Philosophy of Economics

- Daniel M. Hausman(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

CAPITAL THEORY, Utility Theory 23 of x. Saying so, however, commits one neither to utilitarianism nor to the identification of utility with a mental state that is supposed to be the sole goal of action. One can stipulate rather innocuously that option 1 has more utility than option 2 for A if and only if A prefers 1 to 2. Obviously the above conditions depend on nothing peculiar to A; any rational and self-interested agent will engage voluntarily in an exchange only if doing so increases his or her utility thus defined. We can con-clude that rational and mutually disinterested individuals are utility maximizers. To say that individuals are utility maximizers is to say no more than that they do what they prefer. To coax more content out of this plat-itude, economists need to be able to discuss utility functions. These consistently relate options (which are identified with bundles of com-modities) to levels of utility. Individuals can possess utility functions only if their preferences are complete and consistent. Moreover, econ-omists suppose that agents are not satiated. A commodity bundle χ possesses for all agents a greater utility than bundle y whenever χ contains as much of each commodity as y does and more of at least one commodity. As utility maximizers, agents will always exchange a smaller bundle of commodities for a larger one if they can. If economists are interested in how voluntary exchanges of informed, rational, mutually disinterested individuals can lead to an efficient and systematic organization of the economy, they can ignore the mistakes individuals make through irrationality, lack of information, or inade-quacies in the assumption of mutual disinterest. As a first approxi-mation, economists are thus perhaps justified in assuming away satia-tion. If one is interested in how an economy actually works, as opposed to how exchanges can lead to economic order, ignoring these compli-cations is not obviously legitimate. - Berkeley Hill(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

Note that to the grandmother the mince pies are unlikely to be free. Few commodities in life are free goods, that is, they are so plentiful in relation to the wants for them that no allocation is necessary and so they do not have a price, e.g. fresh air and salt water. Most commodities are economically scarce and are therefore priced. The acquisition of them by a consumer is at some cost, and he consequently has to choose how to spend his limited funds in the ways to give him most satisfaction. This is, of course, a typical economic problem of allocating a scarce resource (purchasing power) between alternative uses (the range of goods and services open to the consumer) in pursuit of a given objective (to maximise his satisfaction). Economists attempt to explain how consumers do this using Theories of Consumer Choice. Theories of Consumer Choice The consumer is of fundamental interest to the economist because it is to satisfy the demands of consumers that production takes place. Paradoxically, the objectives which lie behind the behaviour of consumers and the choices they make are among the most elusive because they are complex and for the most part unmeasurable. In the face of these difficul-ties economists have developed several theories to explain consumer behaviour, two of which will be described here — firstly Utility Theory and secondly indifference theory. Both make the reasonable assumption that the objective the consumer has in mind is to get the greatest amount of satisfaction possible from the limited amount of purchasing power he possesses. We begin with Utility Theory which, while simple in concept, contains some difficulties which the second approach, using indifference curve analysis, overcomes.- eBook - ePub

Games and Decisions

Introduction and Critical Survey

- R. Duncan Luce, Howard Raiffa, Howard Raiffa(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

2UTILITY THEORY2.1. A CLASSIFICATION OF DECISION MAKINGThe modern theory of utility is an indispensable tool for the remainder of this book, and so it is imperative to have a sound orientation toward it. Apparently this is not easy to achieve, judging by the many current misconceptions about the nature of “utility.” It is, perhaps, unfortunate that von Neumann and Morgenstern employed this particular word for the concept they created—unfortunate because there have been so many past uses and misuses of various concepts called utility that many people view anything involving that word with a jaundiced eye, and because others insist on reading into the modern concept meanings from the past. We certainly are not going to assert that there are no serious limitations to the von Neumann-Morgenstern theory, but it can be frustrating to hear devastating denunciations which, although relevant to theories of the past, are totally irrelevant to—or incorrect for—the modern theory.Pedagogically, it might be wise to defer this discussion until it is forced upon us in the context of game theory. Certainly, the needs of game theory would provide excellent reason to study the concept; however, it would also necessitate a sizeable digression in what will prove to be an already long argument. Furthermore, Utility Theory is not a part of game theory. It is true that it was created as a pillar for game theory, but it can stand apart and it has applicability in other contexts. So we have elected to present it first. As background, we shall describe in this section how the problems of decision making have been classified, in this way showing where Utility Theory fits into the overall picture. In the next section we shall discuss the classical notion of utility and indicate how, through its defects, it led up to the modern concept. No attempt is made to trace the history of the concept in detail; an excellent history can be found in Savage [1954]. In sections 2.4 and 2.5 we shall present a version of the theory itself, and in 2.6 and 2.7 some of the more common fallacies surrounding it. The chapter closes with a brief discussion of the experimental problems. Appendix 1 - eBook - PDF

- Martha L. Olney(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Utility is satisfaction. Some people think utility is greed, but it need not be so. Whatever gives you satisfaction, whatever gives you happiness, those things give you utility. Paying your rent so you have a place to sleep gives you utility. Buying food so you are not hungry gives you utility. Buying a required textbook so you can earn a higher grade gives you utility. Giving money to the Red Cross for disaster relief because you want to help others gives you utility. Utility is simply the economist’s word for satisfaction. Economists like to count and measure, so they pretend that we can count utility. The units of utility are called utils. This is all make-believe. How satisfied or happy do you feel when you pay your rent? “Pretty good. It’s better than sleeping on the street,” you say. Economists pretend you can put a number on that feeling: “I get 400 utils of satisfaction from paying my rent.” You and I can’t compare how many utils of satisfaction we each get from pay- ing our rent. You can compare your utility from paying your rent with your utility from buying food. I can compare my utility from paying my rent with my utility from buying food. But you can’t compare your utility from paying your rent with my utility from paying my rent. It’s all make-believe, anyway. So you can rank your feelings—shelter is better than food, food is better than clothing, clothing is better than chocolate. But you can’t say who gets more satisfaction from paying their rent: you or me. Economists say: There is no interpersonal comparison of utils. The more you consume of one particular item, the more utility you receive. If one apple is good, two are better. If two are good, three apples are better still. Economists say: Your total utility rises as you consume a greater quantity of any one item. The additional utility you receive from each additional apple is the marginal utility of that apple. - eBook - PDF

- Michael Maschler, Eilon Solan, Shmuel Zamir(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2 Utility Theory Chapter summary The objective of this chapter is to provide a quantitative representation of players’ preference relations over the possible outcomes of the game, by what is called a utility function. This is a fundamental element of game theory, economic theory, and decision theory in general, since it facilitates the application of mathematical tools in analyzing game situations whose outcomes may vary in their nature, and often be uncertain. The utility function representation of preference relations over uncertain outcomes was developed and named after John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. The main feature of the von Neumann–Morgenstern utility is that it is linear in the probabilities of the outcomes. This implies that a player evaluates an uncertain outcome by its expected utility. We present some properties (also known as axioms) that players’ preference relations can satisfy. We then prove that any preference relation having these properties can be represented by a von Neumann–Morgenstern utility and that this representation is determined up to a positive affine transformation. Finally we note how a player’s attitude towards risk is expressed in his von Neumann–Morgenstern utility function. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2.1 Preference relations and their representation A game is a mathematical model of a situation of interactive decision making, in which every decision maker (or player) strives to attain his “best possible” outcome, knowing that each of the other players is striving to do the same thing. - eBook - PDF

- Michael Maschler, Eilon Solan, Shmuel Zamir(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

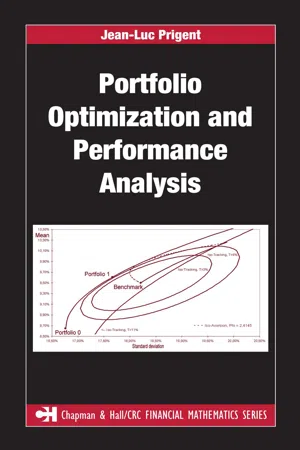

2 Utility Theory Chapter summary The objective of this chapter is to provide a quantitative representation of players’ preference relations over the possible outcomes of the game, by what is called a utility function. This is a fundamental element of game theory, economic theory, and decision theory in general, since it facilitates the application of mathematical tools in analyzing game situations whose outcomes may vary in their nature, and often be uncertain. The utility function representation of preference relations over uncertain outcomes was developed and named after John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. The main feature of the von Neumann–Morgenstern utility is that it is linear in the probabilities of the outcomes. This implies that a player evaluates an uncertain outcome by its expected utility. We present some properties (also known as axioms) that players’ preference relations can satisfy. We then prove that any preference relation having these properties can be represented by a von Neumann–Morgenstern utility and that this representation is determined up to a positive affine transformation. Finally we note how a player’s attitude toward risk is expressed in his von Neumann–Morgenstern utility function. 2.1 Preference relations and their representation • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A game is a mathematical model of a situation of interactive decision making, in which every decision maker (or player) strives to attain his “best possible” outcome, knowing that each of the other players is striving to do the same thing. - Jean-Luc Prigent(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

Therefore, for example, an investor who has a decreasing marginal utility u is necessarily risk-averse. To argue with this kind of criticism, several responses have been given: • First, following Marschak [378] or Savage [449], expected Utility Theory is what “rational” people ought to do under uncertainty, and not nec-essarily what they actually do. This means that if they were perfectly informed and aware of their decisions, they will behave according to expected Utility Theory. • Second, new theories of choice under uncertainty can be introduced to avoid, for example, Allais paradox. During the 80s, the revision of the expected utility paradigm has been intense-ly developed by slightly modifying or relaxing the original axioms. Among several proposals are: the Weighted Utility Theory of Chew and MacCrimmon [120] that assumes a weaker form of the axiom of independence; the Prospect Theory of Kahnemann and Tversky [314] which modifies the axioms much more; the Non-Linear Expected Utility Theory of Machina [367]; the Antici-pated Utility Theory of Quiggin [420]; the Dual Theory of Yaari [507]; and the Regret Theory introduced by Loomes and Sugden [365]. Utility Theory 25 1.5.1 Weighted Utility Theory One of the first theories that was consistent with Allais paradox was the “weighted Utility Theory”, introduced by Chew and MacCrimmon [120] and further developed by Chew [119] and Fishburn [224]. The idea is to apply a transformation on the initial probability. The basic result of Chew and MacCrimmon yields the following represen-tation of preferences over lotteries L = { ( ω 1 , p 1 ) , ..., ( ω m , p m ) } : U ( L ) = i u ( x i ) φ ( p i ) with φ ( p i ) = p i / [ i v ( x i ) p i ] , (1.23) where u and v are two different elementary utility functions. Another approach is the “prospect theory” introduced by Kahnemann and Tversky [314]. Consider the following example where two lotteries are pro-posed.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.