History

1860 Republican Convention

The 1860 Republican Convention was a pivotal event in American history, where the Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln as their presidential candidate. The convention took place in Chicago and marked a significant moment in the lead-up to the Civil War. Lincoln's nomination ultimately led to his election as the 16th President of the United States.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "1860 Republican Convention"

- Homer Adolph Stebbins(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

NATIONAL NOMINATING CONVENTIONS THE REPUBLICAN NATIONAL NOMINATING CONVENTION The auspices under which the National Republican Con-vention met in the Crosby Opera House, Chicago, on May 20, 1868, were not all that could be desired. 1 The friction between an impolitic, unyielding President and a rash, re-vengeful Congress had changed the current of public senti-ment and had created new issues, many previously un-thought of, causing wounds still unhealed. These new issues were largely foreign to those which caused the Civil War. First, questions arose concerning the readmittance of the seceded States and their social and economic conditions, which resulted in the supremacy of the Congressional over the Presidential theory. Secondly, came the issue between the President and Congress over their relative powers. Thirdly, the shorter but equally bitter conflict between the Supreme Court and Congress arose over the powers and functions of each, followed by the withdrawal of the former from the field. Lastly, the attempt to oust the President, with its failure 2 and resultant loss of prestige for the Congressional party, made a situation the entire course of which enveloped the Radical section of the Re-publican party in a cloud of suspicion. The agreement of the delegates 3 at Chicago on the name of Grant, nevertheless, tended to allay alarm. Grant's name appears to have been accepted without serious ques-tion. This naturally lessened the excitement of the conven-tion. Still, considerable interest was awakened over the selection of the vice-president and the formation of a plat-1 Utica Morning Herald, Utica, May 21, 1868. 2 T h e eleventh article of impeachment failed by a vote of g u i l t y , 35; not guilty, 19 (test vote) ; on May 16, 1868. Ten days later the court of impeachment adjourned sine die after reaching the same re-sult on the second and third articles. ' For list of State delegations cf., N e w Y o r k Tribune, May 19, 1868.- eBook - ePub

- Brian Holden Reid(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Will always keep a “Pryor” engagement – a reference to Roger Pryor, a Virginia secessionist. The Convention was just as much theatre as political forum. Groups of men were enjoined to shout chants for their candidate; here Lincoln, a local figure, enjoyed an enormous advantage. Bargains were struck on the convention floor, gossip, the lifeblood of politics and the addiction of professional politicians, was exchanged, and agreement was reached. As Halstead made clear, ‘the amount of idle talking that is done is amazing’.Men gather in little groups, and with their arms about each other, and chatter and whisper as if the fate of the country depended upon their immediate delivery of the mighty political secrets with which their imaginations are big. There are a thousand rumours afloat, and things of incalculable moment are communicated to you confidentially, at intervals of five minutes.… The current of the universal twaddle this morning is that ‘Old Abe’ will be the nominee.Allan Nevins rightly described this gathering as ‘bedlamite confusion’. Experts at political gatherings are often proved wrong in their predictions, and the most striking feature of conventions in the nineteenth century was their propensity for throwing aside famous and accomplished candidates in favour of the comparatively untried and inexperienced man. In 1852 the Democrats had chosen Franklin Pierce, a man overwhelmed by his responsibilities and unequal to the demands of his high office; in 1860 the Republican Party was rather more fortunate.22The confusion and loquacity of the proceedings at Chicago at first sight appeared to be an obstacle to reaching a wise decision as to who should lead the party into the most important race since the unopposed election of George Washington in the first presidential election of 1792. On 16 May David Wilmot, now past his best, was appointed chairman. ‘He is a dull, chuckel headed booby looking man’, Browning thundered in his diary, ‘and makes a very poor presiding officer’.23 - eBook - ePub

The Birth of the Grand Old Party

The Republicans' First Generation

- Robert F. Engs, Randall M. Miller, Robert F. Engs, Randall M. Miller(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER TWOMaking and Mobilizing the Republican Party, 1854–1860

Michael F. HoltMost Americans were taught in high school that the early Republican party was the product of an escalating sectional conflict between the North and South over slavery extension that helped disrupt an earlier system of two-party competition, propel northern voters toward the Republican column, and elect a Republican president within six years of the new party's formation. This clear and straightforward account of the party's birth and infancy continues to possess much merit. In the last thirty years, however, historians have complicated it by demonstrating that the formation and rise to power of the Republican party were considerably more difficult achievements than they appear on their face. This chapter seeks to recapitulate this reinterpretation.The Republican party first emerged in the summer of 1854 as a small part of a broad northern protest movement against the recent passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. That law repealed the ban on slavery north of the 36º 30' line in the as yet unorganized portion of the Louisiana Territory and opened it to potential settlement by slaveholders. In July 1854, the Michigan Republican state platform, the first ever issued by the embryonic Republican party, cogently justified the mission and name of the new party. After denouncing the institution of African American slavery as a “relic of barbarism” and insisting that Congress stop slavery expansion to end the “unequal representation” of the South in Washington, it declared that the purpose of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was to “give the Slave States such a decided and practical preponderance in all measures of government as shall reduce the North…to the mere province of a few slaveholding oligarchs of the South—to a condition too shameful to be contemplated.” It then proclaimed that “in view of the necessity of battling for the first principles of republican government and against the schemes of aristocracy the most revolting and oppressive with which the earth was ever cursed, or man debased, we will cooperate and be known as Republicans until the contest be terminated.”1 - Kenneth F. Warren(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

THE THIRD PARTY SYSTEM 1860–96 By 1860, the Republicans were now the principal alter-native to the Democratic Party in national politics. Meeting at the “Wigwam” in Chicago, the Republicans selected on the third ballot a dark horse candidate, Abraham Lincoln, as the party’s standard-bearer in the general election against a Democratic Party fractured by the slavery issue. Lincoln, who opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories, but believed that the federal government did not have the authority to ban slavery, was elected. The southern states, seeing the new Republican administration as a threat to slavery, seceded from the Union, leading to the Civil War. While Lincoln is most remembered for leading the Union during the Civil War, his administration also established the Department of Agriculture (1862), the Bureau of Internal Revenue (1862), and the Comp-troller of the Currency (1864). Two important bills enacted during Lincoln’s presidency were the Home-stead Act (1862), which gave 160 acres to settlers, and the Morrill Land Grant College Act, which gave federal land to states for the purpose of establishing agricul-tural and engineering colleges. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, ending slavery in the rebellious states. Following the Civil War, the radical Republicans who dominated Congress (over the opposition of Andrew Johnson, who became president after Lincoln’s death), oversaw the reconstruction of the Union, which included the enactment of legislation to improve the plight of the newly-freed slaves, the “reconstruction amendments” (Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments) to the Constitution, and the occupation of the south by federal military forces.- eBook - ePub

The Battles that Made Abraham Lincoln

How Lincoln Mastered his Enemies to Win the Civil War, Free the Slaves, and Preserve the Union

- Larry Tagg(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Savas Beatie(Publisher)

The rules of bare-fisted party politics as practiced since Jackson still applied in 1864, and Lincoln knew the ropes better than anyone. He had not spent countless hours in his office listening to the pleas of thousands of office seekers for nothing. His enormous investment in personal attention to patronage since the moment of his election—so thoroughly distasteful to friends and foes alike, privately and in the press—paid off at precisely this moment. Party bosses such as Thurlow Weed in New York and Simon Cameron in Pennsylvania, men to whom Lincoln had devoted hours, days, weeks in conference, were now solidly in Lincoln’s pocket. In addition, all the paymasters, postmasters, assessors, clerks, customs house officials, marshals, deputies, district attorneys, and Indian agents who Lincoln had personally placed in the last three years were now the “party regulars” on the committees of the Republican state conventions and caucuses, men who could block an enemy and advance their favorite in a thousand ways. As one upstate New York editor observed, “A glance at the list of delegates to the Republican state convention will satisfy anyone that the people have had nothing to do with their selection, and that they represent only the great army of office-holders in our state.”The first Republican state convention was in New Hampshire on January 6. The only item on the agenda was to re-nominate Governor Joseph A. Gilmore, but a young state representative named William E. Chandler took the rostrum and, with the help of a loud chorus of Lincoln men, successfully hijacked the proceedings and rushed through a resolution declaring Lincoln “the people’s choice for re-election to the Presidency in 1864.” (Lincoln was ready with a reward. A few months later, he would appoint Chandler, not yet thirty years old, solicitor and judge advocate general of the Navy Department.)Another trick was played in Indiana. Dissatisfaction was high among Hoosiers, and Governor Morgan, the favorite, was no fan of Lincoln. If left alone, the delegation would have been sent to the Republican convention uninstructed. At the opening of the state party convention, however, in the first burst of enthusiasm, while delegates were still taking their seats and the crowd was cheering every phrase, a friend of Lincoln mounted the stage and read a resolution that praised Lincoln and instructed the delegates to vote for Lincoln at the national convention, and then, in the same breath, read a second resolution that declared Oliver Morton—the unanimous choice—the candidate for re-election as governor. A single terrific hurrah from the hall was taken as a signal that both resolutions were passed. Thus, without any discussion, the Indiana Republicans were committed to Lincoln before all the delegates had even unfolded their chairs. The Chase men threw down their hats and swore in disgust. - eBook - ePub

American Abolitionism

Its Direct Political Impact from Colonial Times into Reconstruction

- Stanley Harrold(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Virginia Press(Publisher)

8Political Success and Failure

An Ambiguous Denouement, 1860–1870

From the 1860 national election campaign through secession, Civil War, and into Reconstruction abolitionists continued their long effort to influence politics and government. During these years they maintained their tactic of combining criticism with encouragement of antislavery politicians. In particular they denounced, ridiculed, and praised Abraham Lincoln as Republican presidential candidate in 1860, president-elect during the secession winter, and during his presidency. They criticized Lincoln mainly because of his moderate and vague antislavery commitment. And, as Radical Republicans engaged in similar criticism, most abolitionist leaders became less distinguishable from the Radicals. To a greater degree than Theodore Parker and John G. Whittier had during the late 1850s, most abolitionists after 1860 embraced the Republican Party as providing the best path toward universal emancipation. By 1863 they had become more consistent in their praise and less likely to criticize. At the same time a minority of abolitionists became more consistently critical of Lincoln and his party. At the Civil War’s end and for several years thereafter, as formal emancipation became reality through political and military means, the issue of what black freedom meant further divided abolitionists in their political tactics. By 1870, however, even those abolitionists who were most critical of the Republicans’ imperfect attempts to protect black civil and voting rights claimed victory.Abolitionist John Brown, through his Harpers Ferry raid, helped shape the 1860 national election. But as in 1856, abolitionists in 1860 had no direct role in the Republican Party’s nominating process or in drafting its platform. The great majority of Republican politicians continued to fear being linked to abolitionists. Conversely Garrisonians and radical political abolitionists (RPAs) remained distrustful of the Republican commitment to denationalization as (at best) a means toward gradually ending slavery. Abolitionists recalled that during the late 1850s, many Republicans had deemphasized the slavery issue as they appealed to northern economic interests, rejected black rights, embraced nativism, and sought to attract northern conservatives. Prior to the May 1860 Republican national convention, National Anti-Slavery Standard editor Oliver Johnson declared, “The Republican Party not merely disclaims . . . any design to interfere with slavery in the States . . . but accepts all the villainies incorporated into law as accomplished facts, not to be disturbed.” Johnson, a longtime Garrisonian, warned against voting for a party that did not favor expunging all support for slavery from the U.S. Constitution.1 - eBook - ePub

Abraham Lincoln: A Press Portrait

His Life and Times from the Original Newspaper Documents of the Union, the Confederacy, and Europe

- Herbert Mitgang(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Open Road Distribution(Publisher)

Chapter 5Lincoln for President

MAY 1860–MARCH 1861Two weeks before the Republican party convention at the Wigwam in Chicago, Lincoln wrote to Senator Lyman Trumbull: “As you request, I will be entirely frank. The taste is in my mouth a little; and this, no doubt, disqualifies me, to some extent, to form correct opinions.” Lincoln spent the time planning strategy with advisers and managers and trying to allay doubts by replying to letters from Republicans in other states on various issues. This would be the culmination of six years of debates and speeches on the question that was tearing the country apart.The day before the convention opened, Murat Halstead, the correspondent of the Cincinnati Commercial, reported that “The city of Chicago is attending to this convention in magnificent style. It is a great place for large hotels, and all have their capacity for accommodation tested. The great feature is the Wigwam erected within the past month, expressly for use of the convention, by the Republicans at Chicago, at a cost of seven thousand dollars. It is a small edition of the New York Crystal Palace.” The colors of different candidates came out; the Seward men wore badges of silk with his likeness and name. The next day the astute Halstead reported: “The current of the universal twaddle this morning is that ‘Old Abe’ will be the nominee.”But it did not seem that way in the general view of the convention because the candidacy of Seward seemed so well organized. Thurlow Weed, editor of the Albany Evening Journal, headed the Seward forces. He was to say later, “there can be no doubt that the nomination which was made is regarded as the very next choice of the Republicans of New York. No other man, beside their own favorite, so well represents the party in the great struggle now going on as Abraham Lincoln.” - eBook - ePub

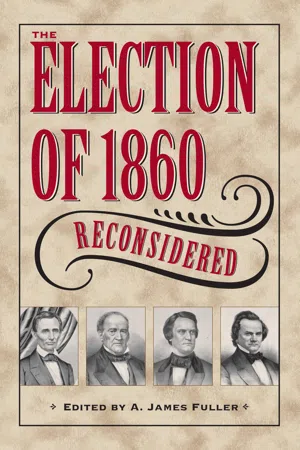

- A. James Fuller(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- The Kent State University Press(Publisher)

15First, though, Lincoln shaped the team that would play on his home field. On May 9, 1860, about six hundred Republicans met for the Illinois state convention in Decatur. When the delegates learned that Lincoln was present, they cheered, lifted him onto their shoulders, and carried him to the platform, then gave him three great gifts. One was their unanimous support for the Chicago national convention. The other was a new persona, created when John Hanks, a cousin of Lincoln’s mother Nancy, and Isaac Jennings entered the “Wigwam,” as the convention hall was known, with two fence rails and a banner proclaiming “ABRAHAM LINCOLN THE RAIL CANDIDATE.” That day, Lincoln became the “rail splitter,” a workingman’s candidate, a far more appealing image than the accurate depiction of him as a successful attorney and man of property.16Fig. 3. The Republican Convention in the Wigwam, Chicago, May, 1860. (Library of Congress)The third present revealed Lincoln at his shrewdest and demonstrated his talents for political strategy and tactics. The convention permitted Lincoln to select four of the twenty-two delegates it would send to the national convention at the larger “Wigwam” in Chicago. Sitting in a nearby grove with Davis, Judd, Leonard Swett, and other Republicans, he made his choices. Picking Gustave Koerner appealed to the Republican Party’s strong German contingent and might help him overcome that group’s support for Seward, who had opposed the nativist Know-Nothing movement far more vocally than Lincoln had. Judd deserved to go anyway as the state party chair but Lincoln made it certain that he would be there, assuring him of a steadfast supporter and blocking Davis’s choice, Wentworth, the loosest cannon in the Illinois Republican Party. Lincoln appeased Davis by naming him a delegate and, by dint of their longtime relationship and Davis’s standing as a judge, his manager in all but name at Chicago. - eBook - ePub

Realignment, Region, and Race

Presidential Leadership and Social Identity

- George R. Goethals(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Emerald Publishing Limited(Publisher)

As the 1860 contest for president shaped up, it was clear that Stephen Douglas would try to capture the Democratic nomination. Although Kansas–Nebraska had made him a hero in the South in 1854, six years later his continued adherence to the popular sovereignty principle, rather than the Dred Scott ruling that slavery could not be excluded from any territory, made him unacceptable there. Douglas succeeded in winning nomination by Northern Democrats, but Southern Democrats held their own convention and nominated John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, the incumbent vice president under James Buchanan.Abraham Lincoln wanted the Republican nomination and worked hard to secure it. His supporters persuaded party leaders to hold its nominating convention in Chicago, as western states, including Illinois, would be crucial for a Republican victory. This gave Lincoln something of a home field advantage in that the dynamics of the convention hall itself favored the state’s favorite son. The leading candidates were William Seward of New York, a long-time opponent of slavery; Salmon Chase of Ohio, an even more outspoken abolitionist; and Edward Bates, a moderate from Missouri. Seward was the front-runner and led on the first ballot. But he had been in politics a long time and had made as many enemies as friends. Lincoln was a moderate from a swing state who had not managed to offend as many people as Seward. He won the nomination on the third ballot.As the election loomed, it was almost a certainty that Lincoln would win. Even though he was not on the ballot in most slave states and most of them would vote for Breckinridge, Lincoln was likely to win most Northern states easily. Support for popular sovereignty had ruined Douglas in the South, and now it was a burden for him in the North. Another complicating factor was the creation of a fourth entry into the race, the Constitutional Union Party, which argued that its platform was the only one that could prevent Southern secession. Its adherents in the Upper South, who supported slavery but still opposed disunion, nominated the elderly John Bell, former senator from Tennessee (Figure 4.1 ).Figure 4.1.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.