History

Brown v Board of Education

"Brown v. Board of Education" was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case in 1954 that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. This decision effectively overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine established in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, marking a significant victory in the civil rights movement and leading to the desegregation of schools across the United States.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Brown v Board of Education"

- eBook - PDF

Badges and Incidents

A Transdisciplinary History of the Right to Education in America

- Michael J. Kaufman(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

4 Brown and Resegregation No period in American history blends an attempt to convert the Founders’ theories into action with an emphasis on the importance of education as dramatically as the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The story of the effort to desegregate the nation’s schools and, in so doing, build a society inclusive of all Americans remains a pivotal episode in the history of education in America. It also offers a fascinating demonstration of the capacity of legal arguments to facilitate cultural change. This chapter will thoroughly analyze Brown v. Board of Education, which declared legally mandated racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The chapter will both analyze the reasoning of the unanimous Supreme Court decision and scrutinize the gaps in the Court’s opinion. In telling the story of Brown, it will emphasize the heroic efforts of the brave parents and students, tireless activists, and visionary attorneys who collectively ended de jure segregation (segregation mandated by law) in the United States. It will also investigate the foundations of this monumental decision – demonstrating how the ingenuity of constitutional lawyers slowly yet steadily laid the groundwork for desegregation and left the Brown Court little alternative but to rule in their favor. Finally, it will examine the progeny of Brown and the often-disappointing results of subsequent Supreme Court decisions dealing with race in schools. This will include an analysis of the lingering effects of de facto segregation (segregation not mandated by law but instead resulting from other factors including housing patterns and demographic shifts). FROM COUNTRY ROADS TO COURTHOUSE STEPS: THE LONG WAR AGAINST PLESSY V. FERGUSON The story of the decades-long struggle to declare legally segregated school systems unconstitutional is, among many other things, a story of the power of education. - Benjamin M. Superfine(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

37 3 Brown and the Foundations of Educational Equality When the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, it set off a wave of education reform that has continued to ripple in law and policy through the beginning of the twenty-first century. Although the jus- tices of the Supreme Court did not expect desegregation litigation to con- tinue indefinitely, the Court decided a major desegregation case as late as 2007. The desegregation movement has also continued to resonate by pro- viding the conceptual and political foundations for most major, large-scale education law and policy reform efforts that have swept through the United States since Brown. Reforms ranging from school finance litigation to legislation focusing on testing and charter schools share roots in the principles of educational equality articulated in Brown and the Supreme Court opinions that followed it. The principles of equality contained in Brown have also resonated through areas of U.S. law and policy besides education. In the years follow- ing Brown, reformers pioneered the area of public law litigation. Instead of simply adjudicating private disputes through a structured, adversarial process, courts became involved in a new kind of case that involves mul- tiple parties and aims at reforming the diffuse institutional structures of government. 1 This sort of litigation surfaced in a range of cases, including those focused on voting rights, prisoners’ rights, and employees’ rights. Given the civil rights approach taken by the Supreme Court in Brown, the case has also assumed a hallowed place in our collective ideas about U.S. government and even society and is widely considered one of the most important cases decided by the Supreme Court in U.S.- eBook - ePub

Education and Sociology

An Encyclopedia

- David Levinson, Peter Cookson, Alan Sadovnik(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

ROWN V . BOARD OF EDUCATIONJennifer L. HochschildPrinceton UniversityBrown v. Board of Education was one of the most important decisions ever made by the United States Supreme Court. It has been criticized for going too far or not far enough, for saying too much or too little, for being too moralistic or too much based in factual claims. Despite those and other criticisms, it stands out for a simple but essential reason: Until it was handed down, it was permissible and even advantageous for public servants and politicians to endorse racial segregation. Twenty years later, the political mainstream did not permit open support for segregation. Furthermore, Brown committed the federal government to ending legal racial segregation, a task that took several decades and eventually involved all branches of government but was eventually accomplished. Those were extraordinary, if insufficient, changes in the United States’ shameful racial history, and Brown v. Board of Education was partly responsible for them.The Antecedents of Brown v. Board of EducationOne must begin with the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and with the history of those amendments over the succeeding century really to understand the import of Brown. The Thirteenth Amendment of 1865 abolished slavery and “involuntary servitude …within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The Fourteenth Amendment followed in 1868, requiring that no state “abridge the privileges … of citizens of the United States.” “It thus ensured that the Thirteenth Amendment (among others) applied within as well as across states. It also (as in the Fifth Amendment) promised “due process of law” and required that states guarantee “equal protection of the laws” to all of their citizens.Over the next quarter century, the Supreme Court narrowed the scope and import of these amendments (along with the Fifteenth, which provided suffrage for male ex-slaves). But it was not until the 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that the vision of racial equality apparently endorsed by the Civil War amendments was definitively squelched. In its decision on the Civil Rights Cases and the Slaughterhouse Cases in the previous decade, the Court had implicitly allowed private racial discrimination by explicitly forbidding discriminatory acts by state and local governments. In Plessy - eBook - ePub

- Lisa Paddock(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

The federal government continues to debate how best to make education both integrated and equal. And racial tensions of all sorts have certainly not disappeared from the American scene. And yet, despite all of its shortcomings, Brown is unquestionably one of the most significant decisions the Court ever has handed down — or ever will. As Justice Arthur Goldberg once observed, America is committed to equality. Brown v. Board of Education helped the nation begin to live up to its promise. - eBook - PDF

Education in Crisis

A Reference Handbook

- Judith A. Gouwens(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

161 6 Data and Documents T his chapter includes a set of primary documents pertinent to education reform and its direction in the United States, as well as some sets of data about students’ academic achievement in the United States. These documents demonstrate reform efforts aimed at both achieving equity in education and improving the quality of education in our nation’s public schools. Brown v. Board of Education The Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), barred states and school districts from segregating schools by race. This landmark case began the push for equity in public educa- tion at the national level in the United States. The text of the decision follows. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (USSC+) 347 U.S. 483 Argued December 9, 1952 Reargued December 8, 1953 Decided May 17, 1954 APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS* Syllabus Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal pro- tection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment—even 162 Data and Documents though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. (a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. (b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. (c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. - eBook - PDF

- Andrew Kull(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

9 Brown v. Board of Education Hopeful that the long-awaited decision in the School Segregation Cases 1 might be the occasion on which the Court finally announced that the Constitution forbade racial classifications, sympathetic observers watched so intently that many saw what they had come to expect. On the Sunday after the decision was handed down, in May 1954, the New York Times put it into historical perspective: It is forty-three years since John Marshall Harlan passed from this earth. Now the words he used in his lonely dissent in an 8-to-1 decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 have become in effect by last Monday’s unanimous decision of the Supreme Court a part of the law of the land. Justice Harlan said: “Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. . . .” Last Monday’s case dealt solely with segregation in the schools, but there was not one word in Chief Justice Warren’s opinion that was inconsistent with the earlier views of Justice Harlan. This is an instance in which the voice crying in the wilderness finally becomes the expres-sion of a people’s will and in which justice overtakes and thrusts aside a timorous expediency. 2 The reader who turns to the opinion in Brown expecting the vindication, or even an acknowledgment, of Justice Harlan’s lonely dissent will in fact find nothing of the sort. The Court’s willingness to confront school segre-gation in 1954 was an act of courage and a wager at the highest stakes, setting the Court’s political authority substantially at risk. The eventual outcome was a monumental triumph for the nation, for the Constitution, and not least for the Court, whose political role underwent a historic transformation as a result of this great case. But the greatness of the case - eBook - PDF

From the Grassroots to the Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education and American Democracy

- Peter F. Lau, Neal Devins, Mark A. Graber(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

Although some scholars question the e≈cacy of judicially directed social reform, ∞≠ Brown unquestionably helped reshape the judiciary’s role in American life by inspiring many interest groups to pursue their goals through litigation. Brown has also played an important role in the larger black freedom struggle, granting to the cause of racial equality the imprimatur of the highest court in the land. Particularly during the first decade after Brown , the decision o√ered the developing civil rights movement both an impor-tant legal precedent and a ‘‘moral resource’’ ∞∞ in its struggle for racial jus-tice. The Montgomery bus boycott, for example, ultimately prevailed when the courts struck down bus segregation in a lawsuit that relied in significant measure on Brown . ∞≤ Moreover, the virulent white reaction to Brown helped to fuel the civil rights movement, which in turn led to the significant anti-discrimination laws of the mid-1960s that went far beyond the school con-text. ∞≥ Brown also helped open the door to legal challenges to other educa- Brown and Black Education in America 363 tional inequities such as the exclusion of the children of illegal aliens from the public schools, various educational practices that discriminated on the basis of gender, and educational barriers to children with special needs. ∞∂ But what has been the impact of Brown on the education of black chil-dren in America? The Supreme Court in Brown found that state-mandated school segregation deprived black children ‘‘of equal educational oppor-tunities.’’ ∞∑ Has Brown in fact produced equal educational opportunity for African American children? The answer is extraordinarily complicated. First of all, it is impossible to assess the impact of Brown without consider-ing the larger context of the decision—other court decisions that both pre-ceded and followed it and a variety of congressional and administrative actions designed to enforce its mandate. - eBook - PDF

Quest for Equality

The Failed Promise of Black-Brown Solidarity

- Neil Foley(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

27 Although the majority of African American and Mexican children continued to attend segregated schools in California, where patterns of residential segregation had been established many decades ear-lier, it is nevertheless significant that California ended de jure segregation seven years before Brown v. Board of Education. California was no racial paradise, but geographically and cul-turally it was a long way from the Deep South and Texas, where it would have been inconceivable that Jim Crow could be struck down by a legislative amendment to the educational code and the courage, at least in one case, of a high school principal. Black v. Brown and Brown v. Board of Education 107 108 Quest for Equality Marshall and the Fund were disappointed, but not sur-prised, that the Ninth Circuit ruling evaded the central argu-ment of the NAACP brief, that race-based segregation violated a citizen’s right to equal protection of the law. In ruling that the school districts had violated the constitutional rights of the Mexican children, it neither adopted nor rejected the so-cial science arguments that segregation did irreparable psy-chological harm to segregated children. NAACP attorney Robert Carter nevertheless regarded the brief as a “dry run” for testing the “temper of the court” with respect to social sci-ence arguments without running the risk of a reversal. 28 “The Circuit Court in affi rming the decision did not go as far as requested in the brief of the NAACP,” wrote Carter, but he felt nevertheless that “This case brings the American courts closer to a decision on the whole question of segregation.” 29 The response of the southern California branch of the ACLU was less charitable: it described Judge Stevens’s opinion as “devoid of social imagination.” 30 The Mendez case galvanized Mexican civil right activists to file suits in Texas where separate schools for Mexicans were main-tained in 122 school districts in 59 counties across the state. - eBook - ePub

What Brown v. Board of Education Should Have Said

The Nation's Top Legal Experts Rewrite America's Landmark Civil Rights Decision

- Jack M. Balkin, Jack Balkin(Authors)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

Sharpe. These include the issues Warren specifically chose to address, the issues that he chose to gloss over or leave in the background, and the issues that were immanent in the case but whose importance only became apparent later on. By comparing Warren’s opinions in Brown I, Brown II, and Bolling v. Sharpe with the opinions of our nine participants, we can see how difficult, complicated, and rich a case Brown v. Board of Education was in Warren’s day and remains in our own. A. The Problem of Writing for the Future Writing an opinion like Brown is not simply a matter of declaring what the law is or should be. It also involves making prudential judgments about the likely effect of the opinion. These include, among other things, how other governmental actors will implement the opinion and to what extent they will resist it, attempt to circumvent it, or refuse to enforce it. The events immediately following Brown are a case in point. Southern politicians and school boards largely sat on their hands for a decade; when they did act it was to devise strategies of resistance to Brown. Some schools in Virginia simply closed their doors to all students; in other places officials adopted school choice programs that effectively preserved the racial status quo. When desegregation cases moved northward, northern politicians were sometimes no less crafty than their southern counterparts in finding artful ways around desegregation orders while stoking racial resentment among their constituents. Popular reception also matters greatly. Individuals and groups can often undermine the desired effect of a Supreme Court opinion. Many southern whites moved their children to private schools in response to desegregation orders, and in the seventies and eighties, many northern whites did the same. An even more common response was to move to largely white suburban areas, which grew increasingly in the last half of the twentieth century - eBook - PDF

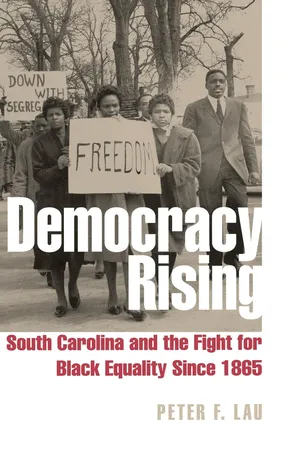

Democracy Rising

South Carolina and the Fight for Black Equality since 1865

- Peter F. Lau(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

For Waring, whose personal and judicial transformation mirrored and gave shape to the emerging post-World War II liberal consensus on race, legal segregation was an anathema to the American way of life that now required purging. The end of Jim Crow segrega-tion had not only become critical to the advancement of racial equality in South Carolina, it had also become, in his view, an imperative of the 206 DEMOCRACY RISING cold war itself. To me the situation is clear and important, he would write in what became his dissenting opinion in Briggs, particularly at this time when our national leaders are called upon to show to the world that our democracy means what it says and that this is a true democracy and there is no under-cover suppression of the rights of any citizens because of the pigmentation of their skins. 26 Although Brings v. Elliott failed to secure a victory against Jim Crow at the district court level, the case became one of five cases in-cluded in the U.S. Supreme Court's May 1954 ruling striking down the doctrine of separate but equal in public education. We con-clude, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. In Warren's conception, education had fast become perhaps the most important function of the state and local governments. It represented the cornerstone of democratic society . . . the very foundation of good citizenship. Public schools, he argued, were key instruments in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional train-ing, and helping him to adjust normally to his environment. To sepa-rate black children from white children in them solely because of their race, he explained in the decision's most controversial passage, generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.