History

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was one of the first political parties in the United States, founded by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams in the 1790s. It advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. The party's influence declined after the War of 1812 and it eventually dissolved, leaving the Democratic-Republican Party as the dominant political force.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Federalist Party"

- Kenneth F. Warren(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

These factions had been known as the Anti-Administration Party or the Anti-Federalists. While the Federalists favored a strong central government, the Republicans supported states’ rights. While the Federalists encour-aged the expansion of manufacturing in the United States, the Republicans favored the maintenance of an agrarian economy. The party contended that many of Hamilton’s policies, including the Bank of the United States, were unconstitutional. Party members objected to President Washington’s neutrality proclamation of 1793, and opposed rati-fication of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain in 1795. They also rejected Federalist proposals for high tariffs, increased military spending, and the establishment of a navy. The party was identified by a number of names during its existence: Republicans, Jeffersonians, or Jef-fersonian Republicans. Their opponents often called them Democrats or Jacobins (a reference to the “Reign of Terror” during the French Revolution). The party began to identify itself as the Democratic-Republican Party after 1816. While the Federalists and Republicans contested the 1794 congressional elections, the 1796 presidential elec-tion was the first that was contested on a partisan basis. John Adams, the Federalist, was elected president. Jef-ferson, who finished second, became the vice president. Rejecting Adams’s invitation to become a part of the administration, Jefferson became its leading opponent. The adoption of the Alien and Sedition Acts by the Fed-eralist-controlled Congress in 1798 was criticized by the Republicans as being unconstitutional because they infringed upon state powers. This became a major issue in the 1798 congressional elections and the 1800 presi-dential election. Jefferson and Madison drafted the Ken-tucky and Virginia Resolutions, which contended that the states could nullify federal laws they deemed to be unconstitutional.- eBook - PDF

- Richard S Katz, William J Crotty, Richard S Katz, William J Crotty(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

(Hofstadter, 1969: 8) The Federalists were a party without a broad mass base. After their defeat in the presidential election of 1800, they soon disappeared, leav-ing a period of one-party dominance by the Jeffersonians. As an indicator of the totality of the divide between parties, the Jeffersonians believed they had established the nature, limits, and purpose of the new nation: ‘The one-party power that came with the withering away of Federalism was seen by the Republicans [Jeffersonians] not as anomalous or temporary, much less as an undesirable eventuality, but as evidence of the correctness of their view and of the success of the American system’ (Chambers, 1963). It would take decades, if not generations, before the full conception of competing ideo-logical and policy-making agendas, both repre-senting legitimately contrasting strains of representation, intended to be resolved by the parties’ election outcomes, was to be accepted. Pragmatic tolerance of an opposition, operat-ing within the bounds of constitutionally-validated institutional structure, evolved over time, but its roots were embryonic in the orga-nizations mobilized in the 1790s. One other point is significant: the party system itself actively and rapidly evolved (more quickly than its popular acceptance). Essentially created (in an uncertain manner) at the birth of the nation and following a period of one-partyism that ended with the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828, it took forms that have come down to us in the contemporary period. Its initial development and perma-nence in American politics provide testimony to its crucial contributions to a functioning democratic system. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE DEVELOPMENT OF PARTIES IN THE UNITED STATES The American party system has a number of distinguishing characteristics, which have influ-enced its evolution and served to define its spe-cial character, its structures, and its operations. - eBook - ePub

- Terence Ball(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Party Government. New York: Farrar and Rinehart.Smelser, Marshall. 1968. The Democratic Republic. New York: Harper and Row.Smith, Abbot. 1942. “Mr. Madison’s War: An Unsuccessful Experiment in the Conduct of National Policy.” Political Science Quarterly 57: 229–46.Wills, Garry. 1981. Explaining America: The Federalist. New York: Doubleday.Wood, Gordon S. 1969. The Creation of the American Republic 1776–1787 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.Young, James Sterling. 1966. The Washington Community, 1800–1828 . New York: Harcourt, Brace.Zvesper, John. 1977. Political Philosophy and Rhetoric: A Study of the Origins of American Party Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Passage contains an image

DOUGLAS W. JAENICKE[19]Madison v. Madison: The Party Essays v. The Federalist PapersAbstract

The most authoritative commentary on the Constitution remains ‘The Federalist’. Yet ‘The Federalist’s’ explanation and defence of the Constitution was always somewhat suspect, since, as the authors themselves admitted, ‘The Federalist’ was a polemic, written to promote the ratification of the Constitution, as well as a work of political philosophy. Moreover, Alexander Hamilton and fames Madison, its main authors, soon parted political company, with Madison in the House of Representatives leading a party in opposition to Hamilton’s policies as Secretary of the Treasury. Madison, known as the ‘Father of the Constitution’, was also the father of the party system, grafted onto the Constitution soon after the government went into operation. This chapter displays the departures that Madison’s thinking as party leader made from the thinking of Madison the co-author of ‘The Federalist’, and argues that these departures comprised a very different and in some ways a superior way of conceiving of America’s form of government. - eBook - PDF

The Party Decides

Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform

- Marty Cohen, David Karol, Hans Noel, John Zaller(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

Republicans led the way in developing party machinery, because they had to overcome the antiparty devices placed by the Federalists in the Constitution. Tracing this process allows us to see how an opposition party develops from scratch, at least in this particular case. Any account of the rise of the Jeffersonian Republican party must begin with policy conflict, of which disagreement over Hamilton’s proposal for a National Bank may stand as illustration. The bank was to be a private institution, but it would be the repository of public funds and would have regulatory power over state and local banks. In Hamilton’s view, the bank would provide a stable national currency, support promising business ven-tures, and encourage foreign investment. But to congressional opponents, the bank would be a gift of interest-free public money to the bank’s private directors and a license to exploit the rest of the banking system. And so it went. Everything Hamilton proposed by way of commercial development was attacked as a giveaway to well-placed friends of the Washington ad- The Creation of New Parties 53 ministration. In many ways, these disputes were a continuation of debates between Federalists and anti-Federalists over the Constitution. The former (prominently including Hamilton) wanted a strong national government to promote development; the latter feared government would be captured by what we would now call special interests. Party conflict had a cultural dimension as well. As noted earlier, the United States was a class-stratified society. “We were accustomed to look upon gentlefolk as being of a superior order,” recalled a modestly born Connecti-cut farmer. “For my part, I was quite shy of them and kept off at a humble distance” (cited in Fischer 1965, 8). Common people, when they took part in public affairs, did not presume to assert their own views; rather, they supported the local gentleman or notable. - eBook - PDF

Social Class and Democratic Leadership

Essays in Honor of E. Digby Baltzell

- Harold J. Bershady(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

They did not prepare to contest the next presidential election, but rued their loss and withdrew to regional, state, and local politics, often in great bitter-ness. The Federalist Party remained active in some states and, indeed, at-tempted with energy to bend the organizational tactics of the Jeffersonians to their own ends. 65 Some Federalists remained an organized voice in the Congress for a decade and a half, but their effective power dwindled rap-idly. The Jeffersonians also regarded their victory as permanent. They pro-claimed themselves the winners of a Revolution of 1800, with overtones of having won just the sort of final triumph over tyranny that the Revolu-tion itself represented to all Americans. They realized that they would face new Federalist challenges in some states and communities. But they were growing confident of their capacity to suppress effective Federalist partici-pation in national politics. 66 Jefferson's confidence rested primarily on his party's newly won control of electoral processes. Still, despite his eloquence in favor of unfettered speech and press in 1800, he briefly followed Adams's model in permitting prosecutions for sedition when angered by attacks on his leadership. He retained an underlying suspicion that committed Federalists dissented from the ideology of liberty that Americans had developed through the Revolutionary movement, hence were untrustworthy as citizens. Although he continued to foster the growth of his own party, Jefferson gave no sign of valuing the Federalist Party as an organization having a continuing im- 2j8 Victor M. Lidz portance in American politics. Most Federalists felt themselves at a loss about what to do beyond holding onto whatever offices they retained. Neither Federalists nor Jeffersonians thought of elections based on compe-tition between parties as a permanent form of political life. It had been an evil that could be tolerated only under the special circumstances of 1800. - No longer available |Learn more

The Complete Works of Theodore Roosevelt. Illustrated

The Naval War of 1812, The Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt, Good Hunting: In Pursuit of Big Game in the West, African Game Trails, The Strenuous Life

- Theodore Roosevelt(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing(Publisher)

During the ten years that had gone by since Morris sailed for Europe, the control of the national government had been in the hands of the Federalists; when he returned, party bitterness was at the highest pitch, for the Democrats were preparing to make the final push for power which should overthrow and ruin their antagonists. Four-fifths of the talent, ability, and good sense of the country were to be found in the Federalist ranks; for the Federalists had held their own so far, by sheer force of courage and intellectual vigor, over foes in reality more numerous. Their great prop had been Washington. His colossal influence was to the end decisive in party contests, and he had in fact, although hardly in name, almost entirely abandoned his early attempts at non-partisanship, had grown to distrust Madison as he long before had distrusted Jefferson, and had come into constantly closer relations with their enemies. His death diminished greatly the chances of Federalist success; there were two other causes at work that destroyed them entirely.One of these was the very presence in the dominant party of so many men nearly equal in strong will and great intellectual power; their ambitions and theories clashed; even the loftiness of their aims, and their disdain of everything small, made them poor politicians, and with Washington out of the way there was no one commander to overawe the rest and to keep down the fierce bickerings constantly arising among them; while in the other party there was a single leader, Jefferson, absolutely without a rival, but supported by a host of sharp political workers, most skillful in marshaling that unwieldy and hitherto disunited host of voters who were inferior in intelligence to their fellows.The second cause lay deep in the nature of the Federalist organization: it was its distrust of the people. This was the fatally weak streak in Federalism. In a government such as ours it was a foregone conclusion that a party which did not believe in the people would sooner or later be thrown from power unless there was an armed break-up of the system. The distrust was felt, and of course excited corresponding and intense hostility. Had the Federalists been united, and had they freely trusted in the people, the latter would have shown that the trust was well founded; but there was no hope for leaders who suspected each other and feared their followers. - eBook - PDF

- Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay, Ian Shapiro(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

Introduction The Federalist Then and Now IAN SHAPIRO Great works of political theory are sometimes written for the ages. They might be occasioned by particular challenges and events, but at least one authorial eye is fixed firmly on posterity. Aristotle’s Politics, Bentham’s Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, and Hegel’s Phi-losophy of Right are all works of that sort. They were conceived of as comprehensive, if not definitive, treatments of their subjects. But some writings on politics achieve lasting recognition even though they are products of more local aspirations. Machiavelli’s Il Principe, Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, and Marx’s On the Jewish Question were all responses to specific challenges of the day, and crafted with particular political goals in mind. Their authors would likely have been amazed to learn that these works would be in print, let alone widely read and translated into most of the world’s major languages, centuries later. Theirs was an exceedingly different path into the canon. The eighty-five letters published in New York’s newspapers between October 1787 and August 1788 that have since become known as The Federalist Papers are decidedly of the latter sort. Published under the pseu-donym Publius, they were the collaborative effort of three men who led the effort to ratify the new constitution. Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) had served as an artillery captain and aide-de-camp to General George Wash-ington during the Revolutionary War and was an organizer of the Con-stitutional Convention. He would eventually serve as America’s first and arguably most influential Secretary of the Treasury. James Madison (1751– 1836), a principal author of the Constitution and its first ten amendments, would in due course serve for eight years each as a member of Congress, as Secretary of State, and as the fourth President of the United States. - Joseph La Palombara, Myron Weiner(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Though it was clear that the country (and the electors) assumed that Jefferson would be President, High Federal- ists schemed to turn the highest office over to Burr. Others sought a deadlock until Jefferson would commit himself to the continua- tion of Federalist policies—the enlarged navy, for example. But Jefferson refused to make any commitment; and the issue remained in doubt for seventeen days and through thirty-five inconclusive roll calls in the House. Finally the majority of the voting states elected marking his ballot for Adams and Jay, thus insuring that, if the Federalist ticket won, High Federalists in the House would not contrive to make Pinckney president. MORTON GRODZINS Jefferson, but only after Federalists from South Carolina, Vermont, and Maryland refrained from voting. At last and in high tension the first fundamental change of leaders took place in the new American nation. IV. The Role of Party in the Change of Leadershif "Our first national parties," wrote William N. Chambers, "rep- resented the conflicting forces of pluralism in American politics, while at the same time they worked to harness them. They provided vehicles for political participation, fulfilled to a remarkable extent the capacities of parties for offering effective choices to the electorate, and brought new order into the conduct of government." 24 This is the conventional view of the important role played by parties in making possible the peaceful changing of leaders in 1800. The view is persuasive because it supplies a simple answer to one of the most complex and mysterious phenomena in political life: the voluntary, peaceful transfer of vast powers from one set of committed leaders to another who by definition are adversaries.- eBook - PDF

Liberty and Slavery

Southern Politics to 1860

- William J. Cooper, Jr.(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- University of South Carolina Press(Publisher)

He thought Pinckney would have done better had not despair of ultimate success paralyzed the exertions of the Federalists. 13 From the beginning the Federalists had been the weaker party in the South, but after 1800 it was devastated. Only in Maryland did the party mount a consistent effort. Gravely weakened else-where, even in states where it had been strong, the party liter-ally almost disappeared. In Georgia and west of the mountains the word Federalist was used only as a term of political oppro-brium. An observer in Kentucky reported in 1803 that only one active politician called himself a Federalist. This cascading de-cline across the political landscape occurred despite a famous southerner leading the Federalist ticket in both 1804 and 1808. Several reasons explain the Federalist debacle. They could never best Republicans on issues that engaged southerners. South-erners supported the Republicans in the 1790s, in part because Republicans pursued issues that most southerners approved; and once in power the Republicans moved on those fronts. They let the Alien and Sedition Acts languish and finally die. They re-pealed the direct tax and cut the federal budget. Then, the whole South cheered the purchase of Louisiana. Division on state issues remained unimportant. Federalists rarely tried to use them to advance the Federalist cause. Just as in the 1790s na-tional questions attracted southern attention and concern. Al-though Federalists did attempt to gain political advantage from the economic hardship caused by the embargo, they did not suc-ceed. Seemingly, the embargo should have given southern Fed-eralists entree to southern voters, but it did not. Southerners also remained prominent in the Republican party. Jefferson and Madison topped a long list of powerful politicians influential in party councils both in Washington and in the states. - eBook - PDF

Foundations of American Political Thought

Readings and Commentary

- Alin Fumurescu, Anna Marisa Schön(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The reality, however, moved further and further away from the presidential rhetoric. Even though, until the end of the eighteenth century, elections were not contested under party labels, newspapers did openly assume partisanship. Appeals continued to be made to the common good instead of sectional interests, but the rhetoric grew increasingly vicious during this period. Each side accused the other of being “a party,” driven by particular interests, while denying themselves that same label. The first party system emerged before the end of the century, opposing Federalists – supporters of a strong central government and a strong executive (like Hamilton) – to Republicans – advocates for state and individual rights (like Jefferson). All economic and particular interests aside, what was at stake was the proper interpretation of popular sovereignty; in other words, of the people’ s two bodies. One party, the Federalists, favored the vision of a corporatist American people, ruled by an aristocracy of merit. The Republicans, on the other hand, promoted a more egalitarian view of peoples, apprehended mainly at state level. The French Revolution served as a catalyst for accelerating the differentiation between the two camps. 12 The people’ s two bodies began to grow apart. For the Federalists, the Reign of Terror that followed the enthusiastic support of the French Revolution was proof of the dangers of egalitarian populism. 13 As Fisher Ames put it, 14 “with the democrats the people is a sovereign who can do no wrong, even when he respects and spares no existing right, and whose voice, however obtained or however counterfeited, bears all the sanctity and all the force of a living divinity.” For the Republicans, on the other hand, the Federalists’ “aristo- cratic” attitude was proof of those pro-monarchical and even tyrannical inclinations against which the French people had justly rebelled. - eBook - PDF

- Jack N. Rakove, Colleen A. Sheehan(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

John Jay, The Federalist, and the Constitution Quentin P. Taylor On October 22, 1787, five days before the appearance of the first Federalist paper, John and Sarah Jay hosted a dinner party in New York City whose guests included Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. 1 Hamilton had recently returned from Albany, where he had pled before the state supreme court, while Madison was attending the moribund Continental Congress. John Jay’s hosting duties repre- sented the social side of his official role as secretary for foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation, but on this occasion his guests were all men of affairs, and politics could hardly be avoided in the charged atmosphere created by the recently proposed Constitution. While it is tempting to picture Jay, Hamilton, and Madison – the future Publius – finalizing their plans over Madeira and rum punch, the secrecy of the project makes it unlikely that it was openly discussed. The authors’ concern for anonymity has clouded the precise origins of The Federalist. While Hamilton is universally credited with the idea for the series, the evidence is circumstantial. He did pen the first number – according to legend on a Hudson sloop returning from Albany – which outlines the plan of the work. Shortly thereafter he is believed to have recruited Jay and then Madison as contributors to the project. Madison later reported that he was courted by Hamilton and Jay, but there is no direct evidence that Hamilton recruited Jay. 2 In light of their decade-long friendship and shared political views, it is likely that The Federalist owed its origins to a degree of collaboration between the two men unsuspected by most scholars. 3 Jay was not only older, but more politically experienced than Hamilton. When Hamilton was penning his first political essays (1774–75), Jay was serving in the Continental Congress, as well as in his native New York, whose first Constitution (1777) was largely his work. - eBook - ePub

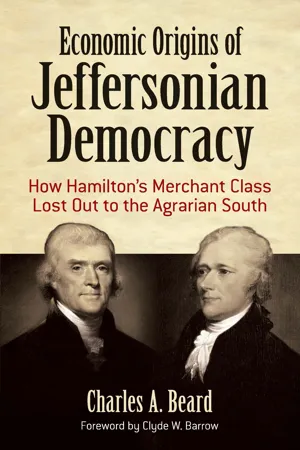

Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy

How Hamilton's Merchant Class Lost Out to the Agrarian South

- Charles A. Beard(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

CHAPTER VIII

THE FEDERALIST ANALYSIS OF THE PARTY CONFLICT

THE vehement assaults of the Republicans upon the capitalistic policies of Washington’s administration forced the Federalists to exhaust the entire armory of their argument.1 Being on the defensive, however, they did not always maintain in their polemical literature that sharpness of class distinction which marked the writings of the Republicans. The wisest of them were, of course, too shrewd to add bitterness to the conflict by unnecessary attacks upon the agrarians as such, and they often employed the good tactics of blurring the economic antagonism by denying its existence or referring to the essential identity of interest between capitalism and agriculture. Yet they could not altogether escape the necessity of recognizing the economic nature of the party division when it became necessary to rally specific groups to the support of Hamilton’s measures. Consequently we find in Federalist literature frank appeals to certain economic groups for political support, denials of the existence of class divisions, assertions that the interests of all classes were identical, and condemnation of the agrarians for their assaults on capitalistic enterprises.When the battle over assumption was on, the newspapers fairly teemed with letters and addresses directed to the financial elements. This was particularly true when there was grave danger that assumption would be defeated. One polemical writer went so far as to threaten Congress with a special convention of public creditors at New York or Philadelphia to “facilitate” the progress of the measure through that body and added a warning that the number of “respectable men” who were holders of the public debt was too large to be treated with indifference. This advocate evidently thought also that the capitalistic element was the very substance of the new government, for he declared emphatically that it would be nothing but a shadow without “a prosperous funding system” — meaning one which would consolidate the state and continental debt and place the holders thereof on a secure basis.2

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.