History

Goryeo Dynasty

The Goryeo Dynasty was a medieval Korean kingdom that ruled from 918 to 1392. It was a time of significant cultural and technological advancements, including the development of movable metal type printing and the flourishing of Buddhism. The dynasty also saw conflicts with neighboring states, particularly the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

8 Key excerpts on "Goryeo Dynasty"

- eBook - ePub

Dress History of Korea

Critical Perspectives on Primary Sources

- Kyunghee Pyun, Minjee Kim, Kyunghee Pyun, Minjee Kim(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Visual Arts(Publisher)

3

Jaeyoon YiGoryeo (918–1392): Dress in Literature, Bulbokjang, and Visual Arts“Korea,” the current name of the country, originated in the Goryeo Dynasty (高麗 , 918–1392), which was a bridge between ancient Korea and the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). The founder, King Taejo (Wang Geon, r. 918–43), overthrew the Late Goguryeo (Hugoguryeo 後高句麗 , 901–18), resettled refugees from Balhae (渤海 , 698–926) after her collapse in 926, and received successive surrenders from Silla (新羅 , 57 BCE –935 CE ) in 935 and Late Baekje (Hubaekje 後百齋 , 892–936) in 936. The Korean peninsula was reunified by Goryeo with territorial expansion to the north, locating its capital in Songdo, present-day Gaeseong in North Korea (see Figure 1.1d ).While Buddhism played a dominant role in the multiple realms of people’s lives and culture as the state religion, Goryeo’s political system was based on Confucianism.1 King Gwangjong (r. 949–75) began to institute the state-wide examination (gwageo 科擧 ) to select government officials based on Confucian knowledge in 958, and issued the dress code (gongbok 公服 ) for officials in 960. In 992, King Seongjong (r. 981–97) established the National Confucian Academy (Gukjagam 國子監 ) to foster the state’s workforce based on Confucian scholarship. For 474 years of the dynastic span, the dress culture of Goryeo was closely interwoven with the state’s political and diplomatic policies. The regulations on dress were set off on the bases of two underlying ideas—Buddhism and Confucianism as the order system within Goryeo society as well as extended to foreign relations with the Chinese Song (宋 , 960–1279), Ming (明 , 1368–1644), Liao (遼 , 916–1125), Jin (金 , 1115–1234), and Yuan (元 , 1271–1368) dynasties.2 - eBook - PDF

East Asia

A Cultural, Social, and Political History

- Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

From 1196 on, power was in the hands of generals of the Choe family, who deposed and appointed kings at will. The Choes, however, could not cope with the emergence of the Mongols. By the 1250s, Goryeo was under firm Mongol control. The Goryeo royal family spent much time in Beijing. Crown princes were required to reside there, and Goryeo princesses were often taken into the Mongol imperial harem. In the late Goryeo period, after the rapid decline of Mongol power in the 1250s, the king Gongmin was able to restore Goryeo political institutions and pro-mote Confucianism. How different was Korea in the late fourteenth century than in the early tenth century, four and a half centuries earlier? After a period of extensive, active contact with Tang China, Korea had found itself separated from China by powerful Inner Asian states. During this period of close contact with In-ner Asian powers, the more Inner Asian side of Korea seems to have been allowed room to flour-ish, as seen in the ascendance of the military, violent succession struggles, and the pervasive practice of slavery. China remained very important but it was no longer the great power of the region. What we tend to think of as the great achievements of Song China, such as the burgeoning economy and high level of urbanization, seem to have had little impact on contemporary Goryeo. China became the source of books and ideas, of Confucian culture and such associated arts as printing and history-writing. Per-haps this encouraged Koreans to be more selective in what they adopted from China and more willing to develop in new directions ideas that had been borrowed from China. geomancy, the Royal Guards, and the personnel bureau. Because Sin Don had no landed estates and no independent economic base, he was totally de-pendent on the king’s favor. - eBook - PDF

Pre-Modern East Asia

A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800

- Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

One of the most significant developments in late Goryeo was the introduction of the Song Dynasty ver-sion of Confucianism, called the Learning of the Way, Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 176 Chapter 10 Goryeo Korea (935–1392) kingdoms, they were all part of a single nation. In this spirit, he praised all the Three Kingdoms for hav-ing strong kings. At the same time, he defended the Silla conquests over Baekje and Goguryeo because their rulers were cruel to their own people, and Silla provided stability to replace the confusion of the other states. Possibly because Silla’s relations with Balhae were bad, he failed to take note of the Balhae kingdom, much less argue that it was part of Korean history, as many Korean scholars insist today. MILITARY RULE AND THE MONGOL INVASIONS (1170–1259) Goryeo suffered a major blow in 1170. A group of military officers, claiming to be enraged by the king’s frequent pleasure trips, overnight poetry competi-tions, and drinking sessions with his refined aristo-cratic friends, carried out a coup d’état. They slaugh-tered numerous civil officials and eunuchs, deposed the king and the crown prince, and put the king’s younger brother on the throne. The deposed king was soon assassinated by a general of slave origins. The coup leaders then appointed military officers to civil posts and made the supreme military council the highest council of state. The military takeover of the civil government was a major turning point in Goryeo history. - eBook - PDF

- (Author)

- 0(Publication Date)

- Rough Guides(Publisher)

Notable among these were the Khitan Wars of the tenth and eleventh centuries, fought against proto-Mongol groups of the Chinese Liao dynasty. The Khitan had defeated Balhae just before the fall of Silla, and were attempting to gain control over the whole of China as well as the Korean peninsula, but three great invasions failed to take Goryeo territory, and a peace treaty was eventually signed. Two centuries later came the Mongol hordes ; the Korean peninsula was part of the Eurasian landmass, and therefore a target for the great Khaans. Under the rule of Ögedei Khaan, HISTORY CONTEXTS 347 1392 General Yi Seong-gye executes last Goryeo kings and declares himself King Taejo of new Joseon dynasty 1443 Creation of hangeul , Korea’s official script, a project of King Sejong 1592 Beginning of Japanese invasions of Korea the first invasion came in 1231, but it was not until the sixth campaign – which ended in 1248 – that Goryeo finally became a vassal state, a series of forced marriages effectively making its leaders part of the Mongol royal family. This lasted almost a century, before King Gongmin took advantage of a weakening Chinese–Mongol Yuan dynasty (founded by Kublai Khaan) to regain independence. The Mongol annexation came at a great human cost, one echoed in a gradual worsening of Goryeo’s economy and social structure. Gongmin made an attempt at reform, purging the top ranks of those he felt to be pro-Mongol, but this instilled fear of yet more change into the yangban elite: in conjunction with a series of decidedly non-Confucian love triangles and affairs with young boys, this was to lead to his murder. His young and unprepared successor, King U, was pushed into battle with the Chinese Ming dynasty; Joseon’s General Yi Seong-gye led the charge, but fearful of losing his soldiers he stopped at the border and returned to Seoul, forcing the abdication of the king, and putting U’s young son Chang on the throne. - eBook - PDF

Cultural History of Reading

[2 volumes]

- Sara E. Quay, Gabrielle R. Watling, Sara E. Quay, Gabrielle R. Watling(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

2000 South Korea begins the Engagement Policy toward North Korea; President Kim Dae-Joong’s announcement of the “Sunshine Policy” 2005–06 The Korean Wave Phenomenon in Asia-Pacific region triggered by Korean TV dramas, “Autumn Tale” and “Winter Sonata” INTRODUCTION TO THE PERIOD Despite the lack of historical records, it is generally recognized that Gojoseon is the oldest of Korea’s kingdoms (2333 B.C.E.). Chinese historian Sima Qian’s Record of a Grand Historian (110– 91 B.C.E.) indicates the kingdom’s existence by describing cultural exchanges between Yin-China, Zhou-China, and Gojoseon. Historical records of later kingdoms have been fairly well preserved. Il Yeon’s Samgukyusah (1281–85), and Yuki—a one-hundred-volume historical record compiled during the Goguryo period—describe Korea’s ancient kingdoms, com- monly recognized as Goguryo (37 B.C.E.–668 C.E.), Baikjeh (18 B.C.E.–660 C.E.), and Shilla (57 B.C.E.– 668 B.C.E.). Later kingdoms such as the United Shilla (668–935), Goryo (918–1392), and Joseon (1392–1910) are described in other historical records, such as Kim Bu-shik’s histories of three kingdoms and the United Shilla kingdom, Samguksaki (A.D. 1145). Goryo History (A.D. 1392–1451) and Record of Joseon Kings (A.D. 1392–1863) are precious historical records that provide detailed knowledge of both kingdoms. What is noticeable in the period of Korea’s kingdoms is that Korea had played the role of a cultural hub that mediated between China and Japan. For instance, according to the Korean Printing Institute’s report, after Ts’ai Lun invented paper-making in 105 C.E., the technique was imported by Goguryo in 593 and further developed by the Baikjeh and Shilla kingdoms. The technological level and the size of the printing sector in those three kingdoms are not exactly known. - eBook - PDF

- Mary E. Connor(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

The cotton plant was introduced and largely replaced hemp, which led to a marked improvement in clothing and textile produc- tion. Other advances included a calendar, gunpowder, and astronomical and mathe- matical knowledge. The firm hand of the Mongols served to sustain the Koryo dynasty for about a cen- tury, but beneath the surface the foundations of government were crumbling. Farm- land continued to flow from public domain to the estates of the nobility. Invasions, repeated attacks by Japanese pirates, and reduced financial support led to increased reliance on Mongol power. As internal dissension and paralysis among Mongol lead- ers spread in the 14th century, Koryo attempted to reassert control, but rival factions supporting the Mongols and the successor Ming dynasty emerged. General Yi Song- gye, ordered to support a mobilization against a Ming invasion, thought this unwise and resisted because he did not believe the smaller kingdom could hold out against the much larger force. Yi and his army attacked the Koryo capital instead. Seizing the throne in 1392, he brought the 474-year dynasty to an end. THE CHOSON DYNASTY (1392–1910) The Early Period: 1392 to the 17th Century Yi Songgye (more commonly called T’aejo) founded Korea’s longest dynasty, last- ing until the 20th century. The new kingdom was renamed Choson. The capital was moved from Kaesong to Seoul, which became the political, economic, and cultural The Choson Dynasty (1392–1910) | 21 center of Korea and has remained so ever since. To protect the new capital, T’aejo ordered the construction of a great 10-mile wall with massive gates, parts of which remained into the 21st century. The Namdaemun Gate, once Seoul’s principal city gate, survived until a great fire destroyed it in 2008. T’aejo continued the traditional relationship with China. At least four missions per year visited the Chinese capital. The purpose of each mission was political but also allowed for cultural borrowing and economic exchange. - eBook - PDF

- Philippe Peycam Peycam, Shu-Li Wang, Michael Hsiao(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute(Publisher)

8 From Ideological Alliance to Identity Clash: The Historical Origin of the Sino-Korean Goguryeo Controversies Anran Wang Goguryeo (Koguryo in old romanization) is the name of an ancient kingdom that existed from 37 bce to 668 ce in present-day North Korea and Northeast China (also known as Manchuria), as well as small portions of South Korea and the Russian Far East. In succession, its capitals were in the present-day Chinese county of Huanren (34 bce – 3 ce), the Chinese city of Ji’an (3–427 ce) and North Korea’s capital city of Pyongyang (427–668 ce). Historical relics, particularly tombs and city walls, abound in these places and their environs. During the seventh century, Goguryeo resisted numerous invasions from successive dynasties in the Chinese hinterland, particularly the Sui Dynasty (581–618 ce) and the Tang Dynasty (618–907 ce), and experienced continuous warfare with other regimes on the Korean Peninsula, such as Silla (57 bce – 935 ce) and Baekje (18 bce – 660 ce). The period during which Goguryeo existed is termed the era From Ideological Alliance to Identity Clash 191 of the Three Kingdoms of Korea (57 bce – 668 ce) because Goguryeo, Silla and Baekje were the three major powers on the Korean Peninsula. Goguryeo was eventually destroyed by a joint force of Silla and the Tang in 668, which led to the Unified Silla Era (668–935 ce) and to the Tang’s rule in northern Korea. Surprisingly, Goguryeo became an issue of severe contention among Northeast Asian countries in the early twenty-first century, more than thirteen centuries after the kingdom’s collapse. A controversy among China and the two Koreas involving governments and academia over whether Goguryeo was a Korean dynasty or a local minority regime of ancient China broke out when North Korea and China nominated their respective Goguryeo relics for UNESCO World Heritage status. - eBook - PDF

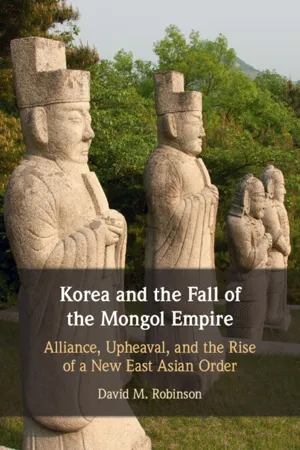

Korea and the Fall of the Mongol Empire

Alliance, Upheaval, and the Rise of a New East Asian Order

- David M. Robinson(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The most important surviving chronicle of the Mongol court in East Asia during these years, Yuan History , tersely notes those dramatic events with little attention to context or cause, but lack of detail should not be taken as lack of importance. Goryeo’ s strategic value as a political and military ally to the Yuan polity grew steadily from the 1340s to the 1360s. A more likely explanation for the minimalist treatment of Goryeo’ s political tumult relates to the circum- stances surrounding the writing of Yuan History . 1 The Ming dynasty compiled the history of its predecessor on the basis of incomplete and multilingual 1 Chen Gaohua, “Yuanshi zuanxiu kao”; Fang Linggui, “Yuanshi zuanxiu zakao”; Wang Shenrong, Yuanshi tanyuan. 71 Queen Anhye m. 1211–1232 Yu Lineage 柳氏 Queen Sungyeong 順敬太后 (Gim Lineage 金氏 of Gyeongju) Princess Qutlugh-Kelmish 齊國大長公主 (Qubilai Khan’s daughter) Princess Gyeguk 薊國大長公主 (Qubilai Khan’s great-granddaugher) Queen Gongwon 恭元王后 (Hong family of Namyang 南陽洪氏) Princess Deoknyeong 德寧公主 (Mongolian noble house) 1322–1375 Royal Consort Hui 禧妃 ?–1380 (Yun family of Papyeong 坡平尹氏) Princess Noguk 魯國大長公主 m. 1351–1365 (Mongolian Noblehouse) Royal Consort Hye 惠和宮主 m. 1359–1374 (Yi Jehyeon’s daughter) Wonjong 1259–1274 Chungnyeol r. 1274–1308 Chungseon (1308–1313) Chungsuk r. 1313–1330, 1332–1339) King Chunghye r. 1330–1332, 1339–1344 Chungmok r. 1344–1348 Chungjeong r. 1349–1451 Gongmin r. 1351–1374 U r. 1374–1388 Gojong (1213–1259) Royal Consort Ik 益妃 m. 1366–1374 (daughter of Prince Deokpung of royal family) Royal Consort Jeong 定妃 m. 1366–1374 (An family of Juksan 竹山安氏) Royal Consort Sin 愼妃 廉氏 m. 1371–1374 Daughter of Yeom Jesin and Grand Lady of Jinhan of Gwon family of Andong Chart 3.1 Chart of succession 72 On the Eve of Wang Gi’ s Enthronement: 1341–1351 records, many of which had been lost or scattered during the war and upheaval of the 1360s.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.