History

Gothic Cathedrals

Gothic cathedrals are large, ornate religious buildings that emerged in the High Middle Ages in Europe. They are characterized by their pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, which allowed for taller and more open interior spaces. These cathedrals often served as the center of religious and civic life in medieval towns and cities, and their construction reflected the wealth and power of the Church and local communities.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Gothic Cathedrals"

- eBook - ePub

- N. D'Anvers(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The first decades of the 12th century were marked throughout Europe, as far as architecture was concerned, by the final breaking loose from the Roman traditions that had so long been accepted as binding, and the revolt against which had been inaugurated more than a hundred years before. The struggle between the old and new methods of building very clearly reflected that of the people for greater freedom of thought and action in the countries in which it took place. The keynote of both was an aspiration after nobler things, and, in architecture, a yearning for religious expression, typified by the pointing upwards of the spires and pinnacles of churches and cathedrals, coincided with the craving of builders for increased lightness and grace of structure. The lofty vaults and complicated systems of buttresses of the Gothic style bore striking witness to the ambitious daring of their designers, a daring more than justified by its results.The term Gothic, that now calls up a vision of ethereal beauty, was, strange to say, first given to the style that grew out of the Romanesque by the artists of the Renaissance as an expression of their contempt for what they looked upon as outworn methods of building, similar to those of the Gothic barbarians in warfare. It very soon, however, lost all association with this most inappropriate comparison, becoming synonymous with all that is most beautiful in the architecture of the period to which it is applied.Gothic Vaulting Gothic VaultingThe most important characteristics of Gothic buildings are the introduction, wherever possible, of vertical or very sharply pointed details, such as highly pitched roofs and gables, spires and pinnacles, pointed arches and pointed vaulting, flying buttresses, that grew ever slenderer and more decorative, leading downwards from the roof, and counteracting the tremendous thrust of the suspended vault of stone, all of true structural value. To these must be added the minor peculiarities of slenderer columns than those of Romanesque buildings, several being often clustered together, mouldings cut into the stone of the capitals of the columns, arcading &c., instead of projecting beyond the surface, the grouping of several windows under the arch, and the increase in the beauty of their tracery. The so-called lancet or long narrow window with stilted head, pointed like an arch, is specially distinctive of Early Gothic, and was later supplemented by the more elaborate rose window, the stained glass in them, and in the more complex groups, adding greatly to the æsthetic effect of the whole building, the many coloured light from them relieving the monotony of the stone work. - eBook - PDF

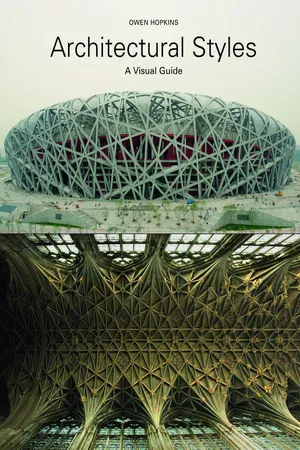

Architectural Styles

A Visual Guide

- Owen Hopkins(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Laurence King(Publisher)

Scholasticism Gothic architecture reflected the prevailing tradition of Scholastic thought that dominated medieval theology and philosophy. Scholasticism, which arguably reached its apogee in Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica (1265–74), sought to blend the doctrines of the Church with ancient Greek and Roman philosophy. It held that truth was not something that could be discovered through reason or experiment, but already existed, pre-ordained by God. This lent great weight to the authority of the Church, which stood on the threshold between Heaven’s perfection and the imperfect Earth, which had fallen from God’s grace. In many ways the Gothic cathedral was intended to stand astride these two worlds. Often housing the relics of a saint or perhaps even a fragment of the Holy Cross, the cathedral offered a tangible link to the divine. This was echoed in the quasi-mystical complex geometry of its vaulting and, of course, in its sheer scale. The often sumptuous stained glass and sculpture of cathedrals had the dual function of relating the Christian story to a largely illiterate laity while also conveying a sense of the divine beauty of the Kingdom of Heaven. International Gothic The innovations of Saint-Denis quickly spread through the Île-de-France, with new cathedrals begun at such places as Noyon, Senlis, Laon and Chartres, and soon reached England. Masons and craftsmen carried the new style across borders. It was under the direction of one such craftsman, William of Sens, that the choir of Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, was begun in the new style in 1174. From its beginnings in France and then England, Gothic architecture became prevalent in Germany, the Low Countries, Spain, Portugal and even Italy. It evolved over the succeeding centuries, being frequently remade and adapted – its use also extended beyond ecclesiastical architecture – before being superseded as the Renaissance swept across Europe. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

Because of the size of the towers, the section of the façade that is between them may appear narrow and compressed. The eastern end follows the French form. The distinctive character of the interior of German Gothic Cathedrals is their breadth and openness. This is the case even when, as at Cologne, they have been modelled upon a French cathedral. German cathedrals, like the French, tend not to have strongly projecting transepts. There are also many hall churches ( Hallenkirchen ) without clerestory windows. Barcelona Cathedral has a wide nave with the clerestory windows nestled under the vault. Spain and Portugal The distinctive characteristic of Gothic Cathedrals of the Iberian Peninsula is their spatial complexity, with many areas of different shapes leading from each other. They are com-paratively wide, and often have very tall arcades surmounted by low clerestories, giving a similar spacious appearance to the hallenkirche of Germany, as at the Church of the ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Batalha Monastery in Portugal. Many of the cathedrals are completely surrounded by chapels. Like English Cathedrals, each is often stylistically diverse. This expresses itself both in the addition of chapels and in the application of decorative details drawn from different sources. Among the influences on both decoration and form are Islamic archi-tecture, and towards the end of the period, Renaissance details combined with the Gothic in a distinctive manner. The West front, as at Leon Cathedral typically resembles a French west front, but wider in proportion to height and often with greater diversity of detail and a combination of intricate ornament with broad plain surfaces. At Burgos Cathedral there are spires of German style. The roofline often has pierced parapets with comparatively few pinnacles. There are often towers and domes of a great variety of shapes and structural invention rising above the roof. - eBook - PDF

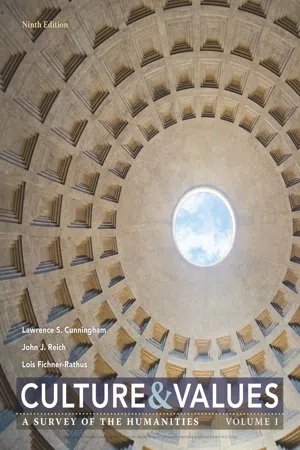

Culture and Values

A Survey of the Humanities, Volume I

- Lawrence Cunningham, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus, , Lawrence Cunningham, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

In Suger’s day, the crypt of the church had already served as the burial place for Frank -ish kings and nobles from before the reign of Charlemagne, and various legends established a connection between the church and Charlemagne himself. Th e fictional Pèlerinage de Charlemagne ( Th e Pilgrimage of Charlemagne ), for example, claims that the relics of the Passion housed at the abbey were brought there personally by Charlemagne when he returned N 30 40 50 feet 1 0 15 meters Ambulatory Radiating chapels uni25B2 10.2 The Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, France, built around 1140, floor plan. The floor plan of the east end of the church shows how the builders used light rib vaults to eliminate the walls between the radiating chapels. Copyright 2018 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. WCN 02-300 312 | CHAPTER 10 The High Middle Ages remain the exclusive purview of the French. By the end of the th century, there were outstand -ing examples of Gothic architecture in England, Germany, and Italy as well. Characteristics of the Gothic Style One of the characteristics of Gothic Cathedrals is an awe-inspiring verticality. Everything seems to strive upward—the clusters of thin columns ris -ing from the nave floor toward “the heavens,” the pointed arches and pinnacles, the lofty ceilings. Another is colored light—an almost mystical light that penetrates jewel-like panes of stained glass, disperses into prismatic hues, and seems to etherealize the solid stone on which it lands. Innovations in structural design—particularly the exterior flying buttress that supported the nave walls without completely abutting them— made it possible to open up large areas of wall to glass ( Fig. 10.4 ). As the Gothic period progressed, all efforts were directed toward the dissolution of stone surfaces. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Global History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The focus of both intellectual and religious life shifted definitively from monasteries in the country- side and pilgrimage churches to rapidly expanding cities with enormous cathedrals like that at Reims (fig. 7-1) reaching to the sky. In these new urban centers, prosperous merchants made their homes and formed guilds (professional associations), and scholars founded the first universities. Although the papacy was at the height of its power, and Christian knights still waged Crusades against the Muslims, the independent secular nations of modern Europe were beginning to take shape (map 7-1 ). In fact, many regional variants existed within European Gothic art and architecture, just as dis-tinct regional styles characterized the Romanesque period. There-fore, this chapter deals with contemporaneous developments in the four major regions—France, England, the Holy Roman Empire, and Italy—in separate sections. The Gothic style spread beyond these areas, however, reaching, for example, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. GOTHIC AND LATE MEDIEVAL EUROPE 1140–1194 Early Gothic ■ Abbot Suger begins rebuilding the French royal abbey church at Saint-Denis with stained-glass windows and rib vaults on pointed arches. ■ Introduced at Saint-Denis, sculpted jamb figures also adorn all three portals of the west facade of Chartres Cathedral. 1194–1300 High Gothic ■ The rebuilt Chartres Cathedral sets the pattern for High Gothic churches: four-part nave vaults braced by external flying buttresses, three-story elevation (arcade, triforium, clerestory), and stained-glass windows in place of heavy masonry. ■ At Chartres and Reims in France, at Naumburg in Germany, and elsewhere, statues become more independent of their architectural setting. ■ Manuscript illumination moves from monastic scriptoria to urban lay workshops. 1300–1400 Late Gothic ■ The Perpendicular style in England emphasizes surface embellishment over structural clarity. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Concise Western History

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

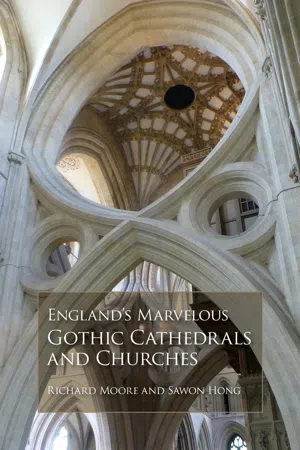

The focus of both intellectual and religious life shifted definitively from monasteries in the country- side and pilgrimage churches to rapidly expanding cities with enormous cathedrals like that at Reims (fig. 7-1) reaching to the sky. In these new urban centers, prosperous merchants made their homes and formed guilds (professional associations), and scholars founded the first universities. Although the papacy was at the height of its power, and Christian knights still waged Crusades against the Muslims, the independent secular nations of modern Europe were beginning to take shape (map 7-1). In fact, many regional variants existed within European Gothic art and architecture, just as dis- tinct regional styles characterized the Romanesque period. There- fore, this chapter deals with contemporaneous developments in the four major regions—France, England, the Holy Roman Empire, and Italy—in separate sections. The Gothic style spread beyond these areas, however, reaching, for example, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. GOTHIC AND LATE MEDIEVAL EUROPE 1140–1194 Early Gothic ■ Abbot Suger begins rebuilding the French royal abbey church at Saint-Denis with stained-glass windows and rib vaults on pointed arches. ■ Introduced at Saint-Denis, sculpted jamb figures also adorn all three portals of the west facade of Chartres Cathedral. 1194–1300 High Gothic ■ The rebuilt Chartres Cathedral sets the pattern for High Gothic churches: four-part nave vaults braced by external flying buttresses, three-story elevation (arcade, triforium, clerestory), and stained-glass windows in place of heavy masonry. ■ At Chartres and Reims in France, at Naumburg in Germany, and elsewhere, statues become more independent of their architectural setting. ■ Manuscript illumination moves from monastic scriptoria to urban lay workshops. 1300–1400 Late Gothic ■ The Perpendicular style in England emphasizes surface embellishment over structural clarity. - richard moore, sawon hong(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Sawon Hong(Publisher)

The English Gothic style can be divided into three periods: Early Gothic, Decorated, and Perpendicular. While these three periods are logical divisions, Gothic design is not easily broken into discrete time periods. Just as there was an overlap between the Norman and the Gothic styles, there were overlaps between the three Gothic periods. As fashions changed, new elements were often used alongside older ones, especially in large buildings such as churches, which were constructed (and added to) over long periods of time. Accordingly, one should treat most architectural dates offered herein as approximate.Each period made full, although variable, use of all three essential features of Gothic architecture: pointed arches, various ceiling designs, and buttresses. Buttressing, not just the flying variety, but all forms, including internal “braces,” were employed. They are in evidence, both outside and inside, where needed to support walls or to shore up unsteady towers. Examples of internal buttressing can be seen at Gloucester Cathedral, while well-known examples of bracing can be seen at Wells and Salisbury.Early Gothic Period (c. 1190 –1250)The most characteristic feature of this period is the pointed arch. Such arch shapes were used throughout the early English churches, most noticeably in the pointed-arch windows. In addition, the walls were higher and the ceilings were constructed of vaulted stone. By contrast, Norman ceilings were often made of wood—perhaps architects were not sure how to span interior spaces using heavier stone. Fine examples of this wooden ceiling can be seen at Ely, Peterborough, and a few other English Gothic churches. The new style piers were clusters of slender shafts surrounding a central pier. Circles with trefoils and quatrefoils (ornamental designs of three, four, or five lobes or leaves, resembling a flower or four-leaf clover) were introduced into the window tracery. The carvings decorating the capitals are highly varied. With the completion of the choir at Canterbury Cathedral by William of Sens in 1175, the style was firmly established in England.Decorated Period (c. 1250 –1340)The Decorated period mainly focused on elaborate stone window tracery. At first, this tracery was based on the trefoil and quatrefoil often combined to form netlike patterns. The Early Gothic lancet windows were replaced by windows of great width and height, divided by complex stone mullions (slender shaft or narrow column used to divide a window) and decorated with quatrefoils or other tracery decorations. The tracery evolved into the greater use of S-shaped curves, which creates flowing, flame-like forms. This period also emphasized elaborately carved capitals, often with floral patterns. The vaulting became increasingly elaborate where shorter ribs are connected to the main ribs to form a variety of patterns. In addition, in a few cases, decorative bosses (rounded caps often found at the intersection of ceiling ribs) were added.- eBook - PDF

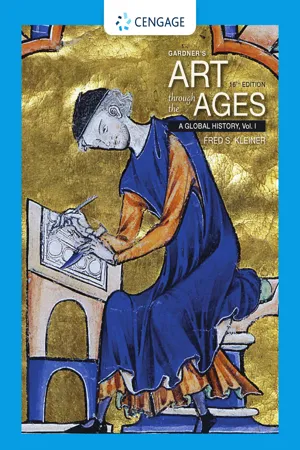

Gardner's Art Through the Ages

A Global History, Volume I

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. France 389 quadrant arches (fig. 12-36, right) beneath the aisle roofs at Dur- ham, also employed at Laon, perform a similar function and may be regarded as precedents for exposed Gothic flying buttresses. The combination of precisely positioned flying buttresses and rib vaults with pointed arches was the ideal solution to the problem of con- structing lofty naves with huge windows (see “High Gothic Cathe- drals,” above, and fig. 13-11). Chartres after 1194. Churches burned frequently in the Mid- dle Ages (see “The Burning of Canterbury Cathedral,” page 353), and church officials often had to raise money unexpectedly for new building campaigns. In contrast to monastic churches, which usually were small and often could be completed quickly, urban cathedrals had construction histories that frequently extended over decades and sometimes centuries, and required a large workforce ARCHITECTURAL BASICS High Gothic Cathedrals The great cathedrals erected throughout Europe in the later 12th and 13th centuries are the enduring symbols of the Gothic age. They are eloquent testimonies to the extraordinary skill of the architects, engineers, carpenters, masons, sculptors, glassworkers, and metalsmiths who constructed and embellished them. Most of the architec- tural components of Gothic Cathedrals appeared in earlier structures, but Gothic architects combined them in new ways. The essential ingredients of their formula for con- structing churches in the opus modernum style were rib vaults with pointed arches, flying buttresses, and huge colored-glass windows. These three features and the most important other terms used in describing Gothic buildings are listed and defined here and illustrated in FIG. 13-11. ■ Pinnacle (FIG. 13-11, no. 1) A sharply pointed orna- ment capping the piers or flying buttresses; also used on cathedral facades. - eBook - PDF

Gardner's Art through the Ages

A Global History, Volume I

- Fred Kleiner(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

n Oculus (8) A small, round window. n Lancet (9) A tall, narrow window crowned by a pointed arch. n Triforium (10) The story in the nave elevation consisting of arcades, usually blind arcades but occasionally filled with stained glass. n Nave arcade (11) The series of arches supported by piers sepa-rating the nave from the side aisles. n Compound pier (cluster pier) with shafts (responds) (12) A pier with a group, or cluster, of attached shafts, or responds, extend-ing to the springing of the vaults. 13-11 Cutaway view of a typical French Gothic cathedral (John Burge). The major elements of the Gothic formula for constructing a church in the opus modernum style were rib vaults with pointed arches, flying buttresses, and stained-glass windows. Copyright 2016 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 382 CHAPTER 13 Gothic Europe centuries, and required a large workforce of quarry workers, masons, sculptors, glaziers, and metalsmiths. Financing for building projects depended largely on collections and public contributions (not always voluntary), and a shortfall of funds often interrupted construction. Unforeseen events, such as wars, famines, or plagues, or friction between the town and cathedral authorities would also often halt construction, which then might not resume for years. At Reims in the 13th century, the clergy offered indulgences (pardons for sins committed) to those who helped underwrite the enormous cost of erecting the city’s new cathedral (fig. 13-1). - eBook - PDF

- Lynn T. Courtenay, Lynn Courtenay(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

272 ENGINEERING MEDIEVAL CATHEDRALS 8o GAZETTE DES BEAUX-ARTS which acted as anchors on either side of the building. Together, these three groups of elements furnished a slender and lofty but adequately rigid superstructure which provided the even loftier mass of the roof with a substantial framework by way of foundation. It has long been recognized that the two most persistent and all-pervading motivations affecting the structure of medieval church architecture were the desire for maximum height and the desire for maximum light. The ceaseless search of the medieval builders for more and more light led to larger and larger window areas and consequently less and less supporting masonry: the structure had to become skeletonized. The equally compelling and avid search for means by which lofty height could be achieved necessitated the most accurate and finished masonry throughout, on the one hand, as well as a skeleton construction precisely and rigo-rously designed to take care of both the intensified and the additional stresses which that increased height imposed. Like all other structural parts of the building, the Gothic roof and its supports were affected by these twin desires for maximum height and light. It has been remarked above that, as the naves became more and more lofty, the window areas increased at the expense of the masonry supports 22 • Along with the nave's increas-ed height and the reduction in the amount of supporting stonework, there was a corresponding increase in the height of the roof itself. This additional height, which was the consequence of making the slope of the roof of ever steeper pitch, inten-sified two serious problems. First, by making the triangular cross-section of the roof larger in area, it increased the amount of timber-work and hence the weight of the roof itself, as well as adding greatly to the extent of the weather surfaces which were covered with lead. - eBook - ePub

How France Built Her Cathedrals

A Study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

- Elizabeth Boyle O'Reilly(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

Gothic art of Brittany—Brittany more a land of shrines than cathedrals—Her religious soul best expressed by her Calvarys—XIII-century cathedral at Dol has fine eastern window—Cathedral at Nantes possesses the last great work of Gothic sculpture—Cathedral of Quimper very Breton in spirit—St. Pol-de-Léon Cathedral entirely complete—The Kreisker is Brittany’s grandest tower—St. Yves of Brittany helped build Tréguier Cathedral.Summing up—Gothic art gave way before the pagan Renaissance and the contempt for legends roused by the Reformation. In the World War France again displayed the spirit that had built cathedrals. Unquenchable idealism of the French race.INDEX : A , B , C , D , E , F , G , H , I , J , K , L , M , N , O , P , Q , R , S , T , U , V , W , Y , Z 583 BIBLIOGRAPHY : A , B , C , D , E , F , G , H , J , K , L , M , N , O , P , Q , R , S , T , U , V , W . 605Illustrations

[Click on the image to view an enlarged version. Images located within paragraphs have been moved slightly to ease reading. (note of etext transcriber.)] Soissons Cathedral. The Transept’s Southern Arm (c. 1180) Frontispiece Poissy. An Early Example of Gothic Vaulting (c. 1135) Facing p. 54 St. Denis-en-France and Its Royal Mausoleums ” 68 Noyon’s Chapter House (1240-1250) Page 83 Senlis’ Tower (c. 1230-1250) Facing p. 90 The Interior of Laon Cathedral (XII Century). View from the Tribune Gallery ” 98 The Oxen on Laon’s Towers ” 106 Notre Dame of Paris. View from the South Page 127 Notre Dame of Mantes (1160-1200). The Contemporary of Paris Cathedral Facing p. 162 The Cathedral of Meaux, Viewed from the Nave’s Aisle ” 168 The Cathedral of Chartres (1194-1240). The Southern Aspect Page 178 The Angel Apse of Rheims (c. 1220) ” 196 The Transept of Amiens Cathedral (1220-1280) Facing p. 204 The Apse of Bourges (1200-1225) ” 214 St. Urbain at Troyes (1264-1276) ” 236 Le Mans Choir (1217-1254). The Double Aisles ” 270 Angoulême Cathedral. A XII-century Cupola Church of Aquitaine with a Typical Façade of Poitou’s Romanesque School ” 290 The Plantagenet Tombs at Fontevrault ” 298 The Plantagenet Gothic Choir of St. Serge at Angers (1220-1225) ” 312 Notre Dame du Port at Clermont-Ferrand. Typical XII-century Church of Auvergne’s Romanesque School - eBook - PDF

- Talbot Hamlin(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

P L A T E X X V Ware Library Ornament from the Erechtheum, Athens Panel from the Ara Pacis Augustae Ware Librar}* From Renaissance in Italy Cantoria, from the Cathedral, Florence Luca della Robbia, architect P L A T E X X V I I u c M D K m i Oí MTWHCl » Ml ! s It.NATII From Perspectiva Pictorum Il Gesù, Rome: vault decoration by Pozzo THE MEANING OF STYLE 201 to create a useful and beautiful building—and are mutually interde-pendent. It should thus be evident that architecture is one of the most com-plete expressions of life there is. Poetry and music and theology give us an expression of the ideals of beauty and goodness prevailing in the times that produced them, and political and economic history tell us much of the practical conditions of existence then current; but in architecture alone can we find an art which by its own character, and because of its very nature, expresses both great sides of existence and mirrors both the wealth and the dreams of humanity. This is a fact which most people unconsciously appreciate. They begin when they are children to think of the Middle Ages in terms of castles and turrets, as well as of knights and men-at-arms. Later, as they grow older, they think of cathedrals, because in these buildings, more than in any other work of the time, the spirit of the thirteenth century flourished complete. The Gothic cathedral is fascinating be-cause its style is what it is, and its style is the direct result of the life of that far-off time. Style in architecture is merely a manner of building that is dif-ferent from some other manner of building. It includes in its scope not only ornament but methods of construction and planning as well. The so-called styles of architecture can be so designated only by limiting the meaning of the word style; they signify merely con-venient heads under which we can classify buildings, first according to date and nation, and second according to the forms originated at those dates and by those nations.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.