History

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson was an American author, educator, lawyer, diplomat, songwriter, and civil rights activist. He was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that celebrated African American art, literature, and music in the 1920s and 1930s. Johnson's most famous work is the poem "Lift Every Voice and Sing," which became known as the "Negro National Anthem."

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "James Weldon Johnson"

- eBook - ePub

- Gene Andrew Jarrett(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938)Few were as influential as James Weldon Johnson was over the generation of writers coming of age in the New Negro Renaissance. In addition to the novel he published first anonymously in 1912 and then under his own name in 1927,The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, Johnson authored multiple books of poetry, a pioneering work of cultural history, an autobiography, and a book on race relations. He also edited the first major anthology of African American poetry and two anthologies of African American sacred music. Not only a man of letters, he was also a successful songwriter, a lawyer, and a diplomat. A “renaissance man” rivaled perhaps only by W.E.B. Du Bois and Alain Locke, he also served as United States consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua, and for a decade was the field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Of the novels published by African American writers between the Civil War and the New Negro Renaissance, none would have agreater impact upon the subsequent shape of African American fiction than Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man .James Williams Johnson was born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1871, the second of three children in a middle-class household. His parents, James and Helen Louise (Dillet) Johnson, had emigrated from the Bahamas in 1866. His father served as a head waiter in a luxury hotel, while his mother was the first African American female public school teacher in Florida. Young James graduated at age 16 from Jacksonville’s largest all-black grammar school, the Stanton School, and enrolled in 1887 at Atlanta University. There he excelled, both as an outstanding scholar-athlete (he delivered the commencement oration in 1894) and as a member of the Atlanta University Quartet that toured New England during the long vacations. After college, Johnson returned to Jacksonville to become principal of his former grammar school, serving from 1894 until 1901. During this time he founded and edited a newspaper, The Daily American (1895–1896), and, in 1898, became the first African American lawyer admitted to the bar in Duval County, Florida. Johnson formed a legal partnership with Judson Douglas Wetmore, an old friend from Atlanta University who had passed for white at the School of Law at the University of Michigan, and twice married a white woman. Most scholars agree that the protagonist of The Autobiography - Michael Nowlin(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The second is marked by Johnson’s turn in the latter half of the decade to the promotional, critical, theoretical, and editorial work that made him instead, in the complimen- tary words of Countee Cullen, “the best of our critic creators” (Letter to James Weldon Johnson, February 14, 1931, JWJP). Johnson became the literary-critical leader he did because he was well positioned to understand the hierarchical logic of international literary relations that made aesthetic measures of universality and modernity far more difficult for some people to meet than for others, but all the more essential to achieve for that reason. Finally, during the high point of the Harlem Renaissance Johnson capita- lized on its success to win recognition for his own literary achievements by collecting as God’s Trombones the new kind of African American poetry he had been working on since 1916 and reprinting his once anonymous novel as a “classic of Negro literature” (Borzoi Books Catalogue 25). Letters from a Foreign Office: Johnson in 1912–13 Johnson took for granted the extent to which the value of literature was determined by a hegemonic system of international relations. Thus in acknowledging in his 1922 preface to The Book of American Negro Poetry that “the colored poet in the United States labors within limitations which he cannot easily pass over,” he conceded the probability “that the first world-acknowledged Aframerican poet will come out of Latin America,” James Weldon Johnson’s Dream of Literary Greatness 51 that indeed the colored Latin American poet’s ability to “voice the national spirit without any reservations” might even offset the African American poet’s “advantage . . . of writing in the world-conquering English lan- guage” (“PFE” 39–40).- eBook - PDF

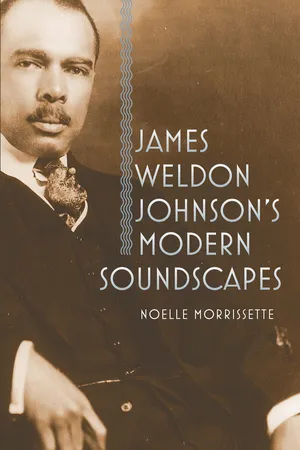

- Noelle Morrissette(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University Of Iowa Press(Publisher)

Photograph courtesy of the James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson Papers, Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. I N t r O d u c t I O N 21 gers (fig. 4); and, finally, the author at his desk and at home—again fea-turing his sartorial flair and delicate features—in photographer Doris Ulmann’s portrait (fig. 5). Black and white viewers’ physical scrutiny of Johnson indicated their preoccupation with black mastery of roles previously understood as the exclusive domain of whites: Bohemian, American Diplomat, even Author. Jack Johnson’s heavyweight title in boxing in 1908 had merely underscored the idea of black physical mas-tery, power, and presence in American life. James Weldon Johnson, as NAACP executive, author, and university educator, drew a similar amount of attention, yet he was the focus of interest quite distinct be-cause of his involvement in literary and political realms that reached beyond the prizefighter’s range. By 1938 Johnson’s reputation as a civil rights leader, both within and outside of the NAACP, was unparalleled. Progressive whites such as E. George Payne, dean of New York University’s Teachers College, and Thomas Elsa Jones, president of Fisk University, believed their friendship with Johnson to be indicative of a future of respectful under-standing between blacks and whites—so much so that, starting in 1934, Johnson was hired by Payne to integrate the faculty by joining it and the curriculum of NYU Teachers College with his lecture course titled Negro Contributions to American Culture. From 1934 until his death, Johnson brought several artists to his NYU classroom to guest lecture, ranging from the widely anthologized poet Countee Cullen to the young and aspiring visual artist Romare Bearden. - eBook - ePub

Walking New York

Reflections of American Writers from Walt Whitman to Teju Cole

- Stephen Miller(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Empire State Editions(Publisher)

30On July 28, 1917, Johnson organized an unusual march in New York. He and W. E. B. Du Bois led a silent parade of ten thousand people up Fifth Avenue. They were protesting the recent race riots in East St. Louis, where whites killed roughly one hundred blacks and drove six thousand from their homes. They also were protesting lynching, which still occurred on a regular basis in the South. “The streets of New York have witnessed many strange sights,” Johnson writes, “but … never one stranger than this.… The parade moved in silence and was watched in silence.” African American Boy Scouts distributed printed circulars that explained why there was a silent march. “We march because we are thoroughly opposed to Jim-Crow Cars, Segregation, Discrimination, Disfranchisement, LYNCHING , and the host of evils that are forced on us.”31In his work for the NAACP, Johnson combatted racism, which he thought “involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.” In his writing, Johnson had a different aim: to persuade blacks and whites that blacks had made an immense contribution to American culture. “The only things artistic in America that have sprung from American soil, permeated American life, and been universally acknowledged as distinctively American, had been the creations of the American Negro.”32Blacks, Johnson argued, have been most influential in the area of popular culture. In the “Preface” to The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), Johnson mentions several popular dances that originated in the black community, but he mainly discusses black music: ragtime, the blues, and Negro spirituals, which he also calls “slave songs” and “Negro folksongs.” He is struck by wonder every time he hears these songs. “The sentiments are easily accounted for; they are, for the most part, taken from the Bible. But the melodies, where did they come from? Some of them so weirdly sweet, and others so wonderfully strong.” In 1917, he argued that “the finest contribution that this country could offer as its own to the world was the American Negro spirituals.”33 In 1925, he and Rosamond published The Book of American Negro Spirituals - eBook - PDF

Legba's Crossing

Narratology in the African Atlantic

- Heather Russell(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- University of Georgia Press(Publisher)

Unlike the main protagonist of his text, James Weldon Johnson was an activist culture worker on behalf of eradicating racial discrimination. In fact, it was Johnson who would much later coin the term “Red Summer” to refer to the bloody summer in 1919, when race wars led to the wounding, displacement, and murder of hundreds of African Americans. Johnson’s involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (naacp), antilynching campaign activities, and literary-politico work with stalwarts like Alain Locke, Jes-sie Fauset, and W. E. B. Du Bois clearly contextualizes the writing of The Autobiography , imbuing his imaginative act with an inescapable politico-social agenda. Art and literature, it was believed, invariably served a politi-cal function in the struggle against racism. W. E. B. Du Bois’s rallying cry, “Thus all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists,” resoundingly captured the tenor of the early generation of black writers whose literary production was inescapably, self-consciously ideo-logical (“Criteria of Negro Art” 100). The debate regarding the ideological implications of what we might today call such circumscribing imperatives would not be challenged until almost fifteen years after The Autobiography was first published. 5 Certainly, at the time of its first publication in 1912, authorial anonymity aside, Johnson subscribed wholeheartedly to the phi-losophy that art and politics were synergistic. Passing for White; Passing for Man The impetus fueling Johnson’s narrative experiment, then, seems clearer if one summons to view the African American male literary tradition. In Race, Citizenship, and Form { 35 } his own autobiography Along This Way (1933), Johnson maintains that he expected that the title The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man would immediately reveal the work’s ironic inflections and implicit relationship to prevailing discourses on black male subjectivity. - eBook - ePub

Artistic Ambassadors

Literary and International Representation of the New Negro Era

- Brian Russell Roberts(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University of Virginia Press(Publisher)

1 Out of this earlier diplomatic milieu, the novel emerged not only as a treatment of the phenomenon of racial passing, as it has traditionally been read, but also as a geopolitically inspired literary exploration of the type of strategic indirection Johnson later influentially imported into the Harlem Renaissance.The Poetics of RevolutionWith the aid of Booker T. Washington, Johnson in 1906 received a consular appointment that transformed his image from that of a bohemian songwriter-musician to a “race man of merit” (Goldsby, “Keeping” 254). Working as a consul situated Johnson as a participant in the United States’ interventionist program for Latin America, and this was especially true during his time in Corinto. His consular notebooks reveal that as the United States plotted to overthrow the Nicaraguan president, Johnson surveilled the activities of Nicaraguan gunboats, wrote reports for the State Department on these activities, and used a secret code to convey the intelligence to the captain of a US gunboat that visited Corinto repeatedly.2 After a US-supported revolution successfully overthrew the Nicaraguan president, Johnson spent time evaluating counterrevolutionary sentiment among Nicaraguans, thereby supporting the United States’ efforts to arrange for the rise of a US-friendly Nicaraguan leader. In November 1910, for example, Johnson sent the State Department a translation of one of many newspaper “articles of an incendiary nature regarding what [anti-US Nicaraguans] term ‘The American Intervention.’” This article quoted a “young man” who declared, “Gentlemen, here is my hand, it is ready to do justice, with it I shall bury my dagger…into the heart of that yankee, who comes to give our country over to those infamous [US-backed Nicaraguan] traitors.…I shall kill him as I would a sick dog, in order to make a warning so that the yankees may know how a weak people answers the brutal impositions of force.” Johnson explained to the State Department, “Such articles are being published daily, and are well calculated to inflame and incite certain elements in the population.” He believed articles of this ilk were responsible for occurrences such as a recent anti-US riot in the nearby city of Leon.3 In spite of these riots, the United States successfully arranged for the former clerk of a US company to assume the Nicaraguan presidency. This move further incensed many Nicaraguans and prompted a revolt that was poised to overtake the town of Corinto, where Johnson worked as the chief US representative. Under intense pressure, Johnson’s facility with rhetorical posturing allowed him successfully to stall the insurgency and thereby to buy time for the landing of twenty-six hundred US Marines for the new president’s protection.4 Johnson later recalled that while in Latin America, he knew the United States should never have intervened in Nicaraguan affairs (Along 283), but he also felt at the time that diplomatic service honed his “intellect and character”5

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.