History

Watts Riot

The Watts Riot was a six-day civil disturbance that took place in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in August 1965. Sparked by tensions between the police and the African American community, the riot resulted in 34 deaths, over 1,000 injuries, and extensive property damage. It brought attention to issues of racial inequality and police brutality in the United States.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Watts Riot"

- eBook - PDF

L.A. City Limits

African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present

- Josh Sides(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Contextualizing the Watts Riot For both black and white Los Angeles, few moments were more terri-fying or more memorable than the six consecutive days in August 1965 when African Americans—mostly young men—rampaged through the streets of Watts and South Central, looting and burning retail stores, beating passing motorists, and attacking the firefighters and police officers who had been sent to quell the disturbance (see figure 13). The grim results—thirty-four deaths (twenty-eight of those who died were black), more than one thousand injuries, four thousand arrests, and $40 million in property damage—sent chills down the spines of whites and blacks across the country. Having weathered racial disturbances in New York City, Rochester, Jersey City, Paterson and Elizabeth in New Jersey, and Philadelphia in 1964, Americans had become familiar with racial violence in cities. But the Watts Riot shocked blacks and whites alike not only because it was the most destructive racial explosion since the Detroit riots of 1943 but also because it took place in Los Angeles, still perceived by many as a relatively favorable city for blacks. As Mayor Sam Yorty had only re-cently told the U.S. Civil Rights Commission: “I think we have the best race relations in our city of any large city in the United States.” 1 Per-haps the most enduring and important legacy of the Watts Riot was that it violently and permanently obliterated that popular myth, almost one hundred years in the making. The Watts Riot of 1965 had many immediate and important effects on ch apter 6 Black Community Transformation in the 1960s and 1970s 169 black Los Angeles. It encouraged many of South Central’s remaining white residents to abandon their efforts at “neighborhood preserva-tion” and simply move out. It was also transformative for the rising group of well-employed black families who sought to flee the rising crime and poverty, and the declining schools, of South Central. - eBook - ePub

Beyond Lip Service

Bringing Racial Justice to Black and Brown Communities

- Anna Maria Santiago, Kelly Patterson, Robert Mark Silverman, Anna Maria Santiago, Kelly Patterson, Robert Mark Silverman(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

From the archives: the Los Angeles riot study

Paul H. StuartThe 1960s was a consequential decade for race relations in the United States. At mid-decade, it seemed that the long struggle to achieve the goal of racial integration would soon be achieved. Congress enacted a series of federal civil rights laws that ended de jure racial segregation and promised to achieve the major goals of the “second reconstruction” – the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Yet less than a week after the signing of the Voting Rights Act, a riot broke out in South Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, following the arrest of a 21-year-old African American driver, Marquette Frye, for suspected drunk driving. Like the Harlem Riots of 1964, which followed the police shooting of 15-year-old Jerome Powell, the Watts Riots differed from many earlier “race riots.” While “race-related collective violence is a recurrent, periodic theme in American history,” riots in the first half of the 20th century “were characterized by violent interracial clashes between blacks and whites, usually initiated by whites” while the disorders of the 1960s “featured clashes between blacks and law enforcement officials” (Lipsky & Olson, 1977 , p. 37). Many argued that the riot, now called by some an uprising, reflected frustration at the continuing challenges of police brutality and segregation during a period of superficial progress. Years later, Frye, who had resisted arrest, told a reporter, “All I knew that day is that I was tired of being treated bad by a policeman” (Szymanski, 1990 , para. 15).Immediately after the riot, the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) initiated the Los Angeles Riot Study (LARS). The study, funded by a grant from the Office of Economic Opportunity, was staffed by faculty members from a variety of social science disciplines. Nathan E. Cohen, a national social work leader who had joined the faculty of the UCLA School of Social Welfare in 1964, served as study coordinator. The Institute of Government and Public Affairs issued a preliminary report in 1967; the final report was issued five years after the riot (N. Cohen, 1970 ), after more than 300 other American cities had experienced serious riots (Lipsky & Olson, 1977 - eBook - PDF

Incarcerating the Crisis

Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State

- Jordan T. Camp(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

21 chapter 1 The Explosion in Watts The Second Reconstruction and the Cold War Roots of the Carceral State The explosion in Watts reminded us all that the northern ghettos are the prisons of forgotten men. —Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., New York, September 18, 1965 In August 1965, the California Highway Patrol stopped an unemployed resident of South Central Los Angeles named Marquette Frye and pro-ceeded to beat him. Frye’s assault ignited the fury of the Black working class in Watts. Many took up burning and looting as their form of pro-test against this particular episode and the more general epidemic of police violence. Over the next five days the masses were on the move. The uprising—popularly known as the Watts rebellion or insurrection— occurred within days of the passage of the historic Voting Rights Act in 1965. National and international attention was drawn to the events, especially as they appeared to contradict the dominant national narra-tive of appeasement and racial overcoming. 1 Moved by the events, Mar-tin Luther King Jr. was compelled to visit Los Angeles. Against the coun-sel of advisors who recommended that King denounce the rebellion and the conditions that produced it, King met with the participants of the then–largest urban uprising in U.S. history. In a press conference shortly after the meeting he stated that the rebellion “was a class revolt of under-privileged against privileged.” While King celebrated the political victo-ries of the freedom movement, he framed the Watts insurrection as the outcome of class anger among those who found their material condi-tions, despite the new legislation, unchanged. 2 In the wake of this encounter, King and his colleagues increasingly worked to articulate alternatives to the race and class inequality they 22 | Chapter One witnessed in Watts. King came to the ethical position that “something is wrong with capitalism. - eBook - PDF

My Los Angeles

From Urban Restructuring to Regional Urbanization

- Edward W. Soja(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

27 My geohistory of Los Angeles begins in 1965, in the bewildering aftermath of one of the most violent and costly riots in U.S. history. The Watts Riots burned down the core of African American LA and had an even larger, worldwide impact. As one of the leading edges of global urban unrest in the 1960s, the Watts uprising announced to the world that the postwar economic boom in the United States and elsewhere was not going to continue with business as usual, for too many benefited too little from the boom. There were riots and uprisings around the world before and after Watts, but none were as violent, as destructive, and perhaps as symbolic of the end of an era and the beginning of a new one as the events of 1965 in Los Angeles. My Los Angeles is in large part an effort to make sense of what happened to LA in the decades following the Watts uprising. Virtually everything contained in My Los Angeles depends on and extends from this first chapter and its central argument that the Watts Riots marked the end of the long postwar economic boom in the United States and sig-naled the onset of a period of crisis-generated economic restructuring that would affect to some degree every major metropolis in the industrialized world. The argument goes one step further to claim and demonstrate that very few if any other metropolitan areas in the world were as deeply restruc-tured and radically changed as Los Angeles, giving to those who study it a remarkable panorama of experiences and expressions from which to draw insight. There is some historical sequencing to this look at the urban restructuring of Los Angeles, but what emerges is certainly not a comprehensive history of LA before or after 1965. Nor is the geography of Los Angeles presented in full and permanent detail. To keep the historical and the geographical developing O N E When It First Came Together in Los Angeles (1965–1992) - eBook - PDF

- Gerald D. Jaynes(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

More National Guardsmen arrived on the scene on late Saturday, and they remained on the scene for nearly a week to restore order. Eleven days after the riot began, it was finally over. AFTERMATH When the Watts Riots ended, residents of the area faced a burned-out and devastated neighborhood. Thirty-four people were dead, 1,032 were injured, 3,775 people had been arrested, and property damage was estimated at $440 million. As the riots were rag-ing, news reports were televised nationwide, and the images inspired rioters in Chicago, Cleveland, Atlanta, and San Francisco. In the aftermath of the riot, coroner’s inquests were held for 32 of the individuals killed. Of those, it was ruled that 26 of the deaths were justifiable homicide, 5 were homicide, and one was accidental. Only one person was ever tried for murder, and he was found innocent of killing a police officer. Nearly 1,000 build-ings in and around Watts had been burned and destroyed, including commercial business and homes. Some stores never reopened because their owners had lost everything and had no money to rebuild. The Watts Riots were among the longest and most destructive in the nation’s history. They erupted at a crit-ical time in the nation’s history, as African Americans were fighting for greater equality more actively than ever before as a result of the civil rights movement. At the same time, however, the growing demands of African Americans created greater tensions in a society that still had further to go in providing full equality. See also Chicago Riots of 1919; Drafts Riot of 1863; Harlem Riots (1935, 1943, 1964); Los Angeles Riots; Race Riots; Racial Violence; Rosewood; Tulsa Race Riot of 1921; Uprisings, Racial Further Reading Burby, Liza N. The Watts Riot. San Diego, CA Lucent, 1997. Salak, John. The Los Angeles Riots: America’s Cities in Crisis. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook, 1993. - eBook - PDF

Soul Power

Culture, Radicalism, and the Making of a U.S. Third World Left

- Cynthia A. Young(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

That incident sparked a six-day riot in which forty thousand rioters and the sixteen thousand National Guard and other law enforcement o≈cers who fought them caused 200 million dol-lars in property damage. By the time the smoke had cleared, thirty-four people were dead, over one thousand people were injured, and four thousand had been arrested. ≤∂ Lyndon B. Johnson expressed his shock and sorrow in a na-tionally televised address, but the ensuing white backlash against Watts and the scores of other riots that followed it began slowly starving his Great Society programs. The Watts Riot proved such a seminal event that it replaced Vietnam as the issue of greatest concern among those polled by Gallup in the fall of that year. ≤∑ Converging at ucla in the early 1970s, the L.A. Rebellion confronted a Watts community that had been economically devastated and politically for-gotten, a community that gave the lie to a post–civil rights common sense that said equality had been achieved, social justice had been attained, and racism no longer dominated U.S. life. L.A. Rebellion filmmakers sought to include Watts in their films in various ways. In the case of Burnett, who grew up in Watts, that meant hiring Watts residents as crew members and actors. When they suddenly failed to show up for shoots, crew members impatiently suggested that Burnett continue shoot-ing, but he insisted on waiting for them, sometimes bailing them out of jail or halting shoots until they resurfaced. ≤∏ Scott MacDonald reads this community-based commitment as one indication that Italian neorealism influenced Bur-nett, though the filmmaker himself denies this, saying that he only became familiar with Italian neorealist film after Killer of Sheep was completed. That influence, however, certainly reached Burnett indirectly via Third Cinema, which was informed by Italian neorealism. - eBook - PDF

The Dark Tree

Jazz and the Community Arts in Los Angeles

- Steven L. Isoardi(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Duke University Press Books(Publisher)

Meanwhile, tensions were escalating. All that was needed was a spark to set South Central afire. The uprising of 1965, then the largest and most destructive in American history, was provoked by a confrontation between law enforcement and resi- dents of South Central. Marquette Frye and his brother, Ronald, were pulled over by two California Highway Patrol officers at the corner of 116th Street and Avalon Boulevard, barely one-half mile west of Watts, on the evening of August 11. A crowd quickly gathered and the lapd showed up in force. The situation rapidly escalated into a confrontation, fueled by a report that a woman in a maternity dress had been struck by one of the officers. It was later learned that the woman in question had been wearing a smock that appeared like a maternity dress but that she was not pregnant. Given the Department’s history, such a story was instantly believable to the people who had gathered and news of it spread rapidly. A spontaneous, mass uprising against the police ensued, in essence an expression of rage and opposition to decades of systematic abuse and bru- talization. As novelist Chester Himes, a resident of Los Angeles in the 1940s, notes, “The only thing that surprised me about the race riots in Watts in 1965 was that they waited so long to happen. We are a very patient people.” 19 The response of the police department to these developments further validated the outrage of the protestors and fanned the flames. Chief Parker’s explana- tion was that “one person threw a rock, and then, like monkeys in a zoo, others started throwing rocks.” 20 His racist views were again trumpeted two weeks later, when he told a national television audience on Meet the Press, “It is estimated that by 1970 45 percent of the metropolitan area of Los Angeles will be Negro; if you want any protection for your home and family . . . you’re going to have to get in and support a strong police department. - eBook - ePub

Cultures of Violence

Visual Arts and Political Violence

- Ruth Kinna, Gillian Whiteley(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

8 He quotes de Gaulle’s televised speech of 7 June 1968, in which the French president also acknowledged that ‘this explosion was provoked by groups in revolt against modern consumer and technical society’ (Viénet, 2014: §8). Viénet notes that:The situationists had foreseen for years that the permanent incitement to accumulate the most diverse objects, in exchange for the insidious counterpart of money, would one day provoke the anger of masses abused and treated as consumption machines.(2014: §6)Indeed, the SI did foresee a build-up of mass dissatisfaction with consumer capitalism: not in France but in the United States. They took a keen interest in US race relations and civil unrest, imagining the Watts Rebellion as the first stage in a broader struggle, signs of which they saw in the 1964 student strike at University of Berkeley that was linked to both civil rights and the Vietnam War. They predicted that African Americans had the potential to ‘unmask the contradictions of the most advanced capitalist system’ (Situ-ationist International, 2006: 195). In the obituary of ‘the man who started the [Watts] riot’, the New York Times described the Watts Rebellion as the biggest insurrection by African Americans in the United States since the slave revolts (25 December 1986). The uprising in Watts was the catalyst for a series of riots across America (1965–67) that I refer to as the ‘long, hot summers’.9At first, it seemed obvious that the Watts ‘riots’ were ‘race riots’, as they were described as such in the Los Angeles Times. For example, on 13 August they reported that an eighteen-year-old girl admitted to throwing bricks and rocks at ‘anything white’ (Hillinger and Jones, 1965). The LA Times also reported on how the riots were perceived abroad. It was front-page news in several countries, including the UK and South Africa. On 15 August, under the headline ‘Reds Call L.A. Rioting Evidence of Race Bias’, they reported that the foreign communist press was taking the opportunity to highlight US discontent (Associated Press, 1965). The New China News Agency is reported to have said that the riot was evidence of ‘a general outburst of their (negroes) pent-up dissatisfaction’ – the brackets, we assume, were inserted by the LA Times - eBook - PDF

Art and the City

Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles

- Sarah Schrank(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

57 At 3:00 on Saturday morning, 3,356 National Guardsmen were in the streets of south central Los Angeles. At 8:00 p . m ., Governor Brown insti-tuted a curfew, and by midnight on Saturday there were over ten thou-sand National Guardsmen on active duty in Los Angeles. The curfew was finally lifted on Tuesday, August 17. A frustrated response to high unem-ployment, a dire education system, a lack of social services, a history of police violence, and a dearth of public transportation in a neighbor-hood where less than 14 percent of residents owned cars, the riot left 34 people dead, 1,032 injured, and approximately 4,000 arrested, 500 of whom were under eighteen years of age. The McCone Commission esti-mated damage to stores and automobiles to be over $40 million. 58 As shocking as the televised images were to Americans all over the country, black Los Angelenos knew that trouble had been brewing for a long time. As the novelist Chester Himes puts it, ‘‘the only thing that sur-prised me about the race riots in Watts in 1965 was that they waited so long to happen. We are a very patient people.’’ 59 The Watts Riot forever changed national perceptions of American urban race relations, dulled Los Angeles’ sunshine booster image, and Figure 37. Nuestro Pueblo during the 1965 Watts uprising. The very top of the frame is marked by smoke and fire. Photograph by Roger Coar. Imagining the Watts Towers 153 reoriented how Rodia’s towers would be publicly represented as the city was catapulted into the American popular consciousness as an emblem of urban blight and black revolution. With the national spotlight on Los Angeles, Watts, and anything associated with it, was too charged for lighthearted editorials about an eccentric Italian tile setter and too dan-gerous to attract art-loving tourists. Rodia’s grateful-immigrant gift to America seemed more appropriate as an emblem of urban failure. - eBook - PDF

Troubled Pasts

News and the Collective Memory of Social Unrest

- Jill Edy(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Temple University Press(Publisher)

The following week, the magazine further developed its theme that a political/economic approach to the unrest in Los Angeles was the appropriate response. It observed that while force was a necessary first response, it “was not the final answer to the conditions that make riots” (After the blood bath 1965, 14). While it reported Lyndon Johnson’s speech comparing the rioters to Klansmen, it surrounded this with reports of two other speeches, which it claimed balanced the need for law and order with the need to attack the “causes” of the violence. It was the attack on these causes, Newsweek claimed, which were the “real meaning of Los Angeles.” However, the magazine stops short of arguing that the cause of the riots was social injustice. Time also began by describing the poor social conditions in Watts and the failure of city and federal officials to ameliorate those conditions. It reported that federal programs had prevented riots in cities where there had been violence in the summer of 1964, a claim that was probably contestable but reported as fact. U.S. News and World Report examined and rejected economic pri-vation as a cause of the riots, continuing to emphasize individual responsibility: The Watts area, where the riots centered is densely populated, almost entirely by Negroes, many of whom are jobless and more than half of whom get some form of government assistance. But its housing is a far cry from the tenement slums of New York’s Harlem. The crime rate in Watts is high. More than 500 of its youngsters are parolees. (Race friction 1965, 23–24) The implication is that conditions are not so bad and the government has responded adequately. The economic deprivation narrative adopts the language of human dignity that had long been a part of mainstream civil rights, but adds 3 8 T RO U B L E D PA S T S R E A L -T I M E N E W S 3 9 demands for economic opportunity to existing demands for equal treat-ment for African Americans. - eBook - PDF

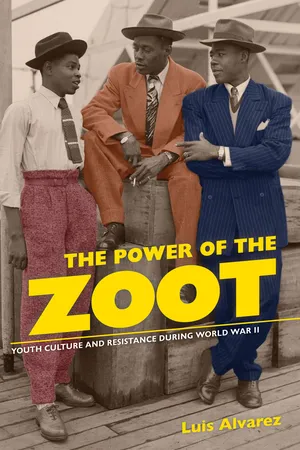

The Power of the Zoot

Youth Culture and Resistance during World War II

- Luis Alvarez(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Race Riots across the United States 201 national belonging during World War II. Although the riots sprang from local economic, social, and political conditions, each was also part of a growing trend among whites toward mob and vigilante violence as a response to the increased cultural, economic, or political self-activity of nonwhites. While the agents of violence varied, from white servicemen and Mexican American youth in LA to white laborers in the South and black residents of Harlem, and while the behavior of the rioters ranged from the symbolic stripping of victims to looting and murder, the riots were all fueled by wartime shifts in patterns of employment, demogra-phy, and xenophobia. Increased competition for jobs, housing, and pub-lic services was often reflected in racial terms, particularly when many whites panicked over diminution of what might be called their economic, political, and social overrepresentation as more nonwhites gained access to home-front resources. The riots also revealed how wartime race rela-tions were gendered, as nearly every incident was preceded and deeply shaped by rumors of Mexican American or African American men hav-ing committed sexual violence against white women. As historian Paul A. Gilje suggests, studying riots can help show how different class, racial, and ethnic groups engage one another; riots serve as important mechanisms for change by reflecting social discontent. Moreover, they sometimes shift economic arrangements, affect political policy, and, perhaps most important for the purposes of this chapter, illuminate instances when ordinary people articulate critiques of soci-ety. 4 Despite differences in the participants, immediate causes, and events, each riot during the summer of 1943 can be viewed as either an effort to claim dignity and national belonging in the face of the dehu-manization and alienation of wartime or an effort to deny the dignity and national belonging of those considered unworthy.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.