Languages & Linguistics

Beowulf

"Beowulf" is an Old English epic poem that tells the story of the hero Beowulf and his battles against the monster Grendel, Grendel's mother, and a dragon. The poem is a significant work of Anglo-Saxon literature and provides valuable insights into the language, culture, and society of the time. It is written in a poetic form and is one of the earliest known works of English literature.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Beowulf"

- eBook - PDF

- Ruth A. Johnston(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Arche- ology continued to uncover new finds that shed light on the material culture of Beowulf's world, but scholarly efforts with the poem turned more to its meaning as literature. How do the characters interact? What is the meaning of a certain incident? How is imagery used? The traditional tools of literary study—theme, character, language, imagery—were turned toward Beowulf with good effect. It is now possible to read many detailed studies of how the poem fits into the tradition of the time, and how its ideas link it to our time. (For a detailed literary analysis, see Chapter 7, "Literary Techniques.") This revaluation is why Beowulf turns up in so many high school and college English courses. While it is so different from modern works, it contains the essential parts of great literature. It is unique in many ways, 14 A COMPANION TO Beowulf just as its manuscript is rare and precious. No other work in English can tie together so many time periods, while still using character and theme in recognizably modern ways. No other work in Old English presents so many levels of complexity. While showing us a different culture, it poses contemporary questions, and raises issues of enduring significance. IN DEPTH: W H Y THE DANES? Why was the story of Beowulf, set in Denmark and Sweden, written in Old English by an Anglo-Saxon? As far as we know, there is no poem or story about Beowulf in Danish or Swedish, but only in Old English. Given the unpopularity of Danish pirates in England, who would take the trouble to preserve a very long poem about them? Who would want to hear it recited or read out loud? There are a few theories, but no one can give a definitive answer to these questions. One possibility is that the poem of Beowulf'was retained from the era when Angles, Saxons, and Jutes lived near Denmark and may have shared culture and history. They may have heard of the fabulously strong and brave prince of Geatland and sung his legendary exploits. - No longer available |Learn more

- Joseph Black, Leonard Conolly, Kate Flint, Isobel Grundy, Don LePan, Roy Liuzza, Jerome J. McGann, Anne Lake Prescott, Barry V. Qualls, Claire Waters(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Broadview Press(Publisher)

Most critics agree that the heroic action of the poem is thoroughly accommodated to a Christian paradigm; they disagree, however, on the meaning and purpose of that accommodation. Beowulf is a secular Christian poem about pagans that avoids the easy alternatives of automatic condemnation or enthusiastic anachronism. While early scholars tried to find a single source for the poem’s complex and peculiar texture—whether in pure Germanic paganism or orthodox Augustinian Christianity— more recent work recognizes that Beowulf , like the culture of the Anglo-Saxons themselves, reflects a variety of interdependent and competing influences and attitudes, even a certain tension inherent in the combination of biblical, patristic, secular Latin, and popular Germanic material. The search for a single “audience” of Beowulf , and with it a sense of a single meaning, has given way to a recognition of a plurality of readers and interests in Anglo-Saxon England. The author of the poem (for the sake of argument, let us say the person who was responsible for its commitment to parchment) was certainly a Christian: the technology of writing in the Anglo-Saxon period was almost entirely confined to monastic scriptoria. The manuscript in which Beowulf is preserved contains a saint’s legend and a versified Bible story. Moreover the poet indicates a clear familiarity with the Bible and expects the same from his audience. Though the paganism of Beowulf’s world is downplayed, however, it is not denied; his world is connected to that of the audience but separated by the gulf of conversion as much as by the seas of migration. Beowulf seeks to explore both the bridges and the chasms between the pagan past and the Christian present; it teaches secular readers how to be pious, moral, and thoughtful about their own history, mindful of fame and courage while aware of its limitations and dangers. - eBook - PDF

Ingeld and Christ

Heroic Concepts and Values in Old English Christian Poetry

- Michael D. Cherniss(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

17 For full discussions of the various historical and fabulous elements in Beowulf see the introduction of Klaeber's edition of the poem, and R. W. Chambers, Beowulf: An Introduction to the Study of the Poem with a Dis-cussion of the Stories of Offa and Finn, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, Eng., 1959). A noteworthy recent attempt to unravel the Germanic pre-history of the HEROIC POETRY AND Beowulf 125 or forms the oral poetic antecedents of Beowulf took, 18 but few scholars question the basic assumption that the poem which we have today has its roots in Germanic heroic tradition. 19 More-over, it should be tolerably clear from the preceding chapters that heroic ideals, embodied in the concepts which I have des-cribed, pervade the poem. The conduct of Beowulf, Wiglaf, Hrothgar, and the other heroes of whom the poet speaks ad-heres strictly to a code based upon loyalty, vengeance and treasure, while the punishment for violating this code is exile. I hope I need not labor the point. At the same time, however, Beowulf appears to be a Christian poem insofar as its poet is certainly a Christian of some sort and his poem is liberally salted with Christian sentiments and allusions. The problem with which we must deal here is that of determining as precisely as possible in what way and to what degree Beowulf is a Christian poem. The Christianity of Beowulf continues to be the subject of apparently endless debate. As it is usually formulated, the main point of contention is whether Beowulf is an 'essentially Chris-tian' or 'essentially pagan' poem. As I pointed out earlier, how-ever, we are not at all concerned in this study with 'paganism' in the strict sense of the term. The concepts which I have des-cribed embody essentially secular moral values and have nothing apparent to do with Germanic religion. They are 'pre-Chris-tian', 'Germanic', and 'heroic', but not 'pagan' or 'heathen'. - eBook - PDF

- Anonymous, R.M. Liuzza(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Broadview Press(Publisher)

A literary work in oral circulation is always new, recreated at each performance; in effect it has no history, no matter how ancient its traditional narrative or style may be. Even if the ultimate roots of Beowulf are in performance and tradi-tion, however, we should still consider the origins of the surviving text. Beowulf 21 1 For discussion of this topic see Benson, “Literary Character,” and Russom. Writing fixes a literary work in a particular form—relatively speaking, for manuscript copies are subject to scribal alteration in the course of their transmission 1 —and this form should bear the marks of its context, whether linguistic or historical. Earlier critical opinion on the date of Beowulf placed the genesis of the poem in the late seventh or early eighth century, relatively early in Anglo-Saxon literary history. In 1982 a volume of essays on The Dating of Beowulf (edited by Colin Chase) offered a series of vigorous challenges to this received opinion, and since then many scholars have drifted away from their earlier con-sensus and toward a later date (ninth or tenth century) for the poem’s composition. Others, notably R.D. Fulk in the 2008 revision of Klaeber’s Beowulf , have restated and reinforced arguments for the tra-ditional earlier date. The range of current opinion on the question is limited only by the absolute limits of the poem’s possible date, c. 520 (when Gregory of Tours says the raid of Hygelac took place) and c. 1000 (when the surviving manuscript was written). The dialect of the poem offers no indication of its origins: like most surviving works of Old English poetry, the language of Beowulf is largely late West-Saxon, with some element of Anglian (northern) vocabulary, a kind of poetic mixture not easily traced to one time or place. Moreover, Old English orthographic habits were somewhat fluid, and scribes might well have modernized and altered the dialect of an older poem in the course of their copying. - eBook - PDF

- Craig Williamson(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

The sense of isolation and mourning in “The Wife’s Lament” provides a more articulate analogue to the mourning of the anonymous old woman after Beowulf ’s death. The religious poem, “Vainglory,” offers a context for reading Hrothgar’s ser-monic advice to Beowulf to avoid the perils of pride. “Cædmon’s Hymn” 24 | B E O W ULF offers a creation song like the one sung in the hall of Heorot. The treatment of loyalty and betrayal in “The Battle of Maldon” sheds light on Wiglaf ’s loyalty and the Geats’ cowardice at the end of Beowulf. Even the “mon-strous” and unknown creatures of the riddles may offer a playful analogue to the more serious monsters that haunt the Danish hall. GENRE AND STRUCTURE Beowulf has often been considered the earliest English epic, though it does not closely resemble classical epics often associated with the term. Tolkien preferred the term “heroic-elegiac poem,” emphasizing the movement toward an elegiac tone in the latter half of the poem (1936, 275). Perhaps the poem, like the Danish hall Heorot, moves from building to burning, from epic to elegy. The editors of Klaeber 4 suggest calling it “a long heroic poem set in the antique past” (clxxxvii), which is an apt, broadly generic description. The poem not only moves back and forth between epic and elegy, between histor-ical materials and mythic elements; it also contains different subgenres. Harris notes that “the Beowulf ian summa includes genealogical verse, a creation hymn, elegies, a lament, a heroic lay, a praise poem, historical poems, a flyting, heroic boasts, gnomic verse, a sermon, and perhaps less formal oral genres” (236). Paradoxically it both draws into itself a variety of Old English genres and also stands finally as an unmatched genre in itself. The poem does not have a straightforward chronological structure. - eBook - ePub

- Derek Pearsall(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Beowulf , 793 has maybe a special significance, since it is a human enough assumption that a poem glorifying Scandinavian heroes would not be popular when their descendants were plundering the country.It would be hard to go much beyond this. Eighth-century Northumbria retains most of one’s favour as a speculative home for Anglo-Saxon poetry, but it may be partly because the culture of the kingdom in this period is so richly documented. If we knew more of Offa’s Mercia, it might provide an equally attractive cultural context for vernacular poetry in the late eighth century: the only conceivable compliment in Beowulf is to Offa, in the reference (1931–62) to his legendary predecessor and namesake, king of the continental Angles, and it was to surviving Mercian scholarship that Alfred turned when he began to rebuild.94 It may not be fanciful, however, in discussing provenance, to suggest that Beowulf has something in common with the great surviving monuments of Northumbrian art of the period, such as the carved crosses of Ruthwell and Bewcastle, and the Lindisfarne Gospels. The blending of Christian, classical and ‘barbaric’ elements in the poem may be compared with similar blending in the Lindisfarne St Matthew.95 The picture, whether it is imitated from the Ezra portrait in the Codex Amiatinus or from some common model, derives its design and figure-posture and the whole idea of a picture that ‘tells a story’ from sixth-century Italian art and ultimately classical sources, just as the poem derives its concept and some of its methods of narrative from Virgilian epic. But the effect of the picture is quite different from the rather placid representationalism of the Ezra portrait: colour is used purely decoratively, there is no relief, and the handling of line has been invaded by a vigour, authority and freedom derived from barbaric art. It is a marvellous picture, humane and moving in a way that the purely barbaric ‘carpet-page’ in the same manuscript is not, and its strength is in its blending of traditions. Tentatively, one might suggest that the ‘barbaric’ elements in Beowulf such as the Germanic story-materials (represented in ‘pure’ form in Finnesburh ) and the formulaic technique, contribute similarly to its strength. Likewise, the Ruthwell and Bewcastle crosses derive many of their sculptural characteristics—developed plastic sense, use of narrative, the vine scroll ornament—from Mediterranean models, perhaps even local Romano-British remains, but their essential character is in the blending of these motifs with the native taste for repetitive ornament, interlace and zoomorphs.96 - eBook - PDF

Critical Approaches to Six Major English Works

From "Beowulf" Through "Paradise Lost"

- R. M. Lumiansky, Herschel Baker, R. M. Lumiansky, Herschel Baker(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

B. J. Timmer's Beowulf: The Poem and Its Poet, 7 after stressing the importance of the number three in the structure of the poem, reaches a conclusion in many ways reminiscent of Tolkien : Beowulf . . . was written for the purpose of strengthen-ing the Christian faith of the readers, rather than as a speculum principum. Although not an allegory, it de-picts the powers of Utgarör invading the happiness of man as the evil powers that beset any man in this world and Beowulf as the representative of what is good. The battle of good and evil is the poet's theme, but he embroi-dered it upon a pagan background. But the poet knows 6 Critical A pproaches to Six Major English Works —and that is why the poem is not an allegory—that man is mortal and that the powers of evil remain: Beowulf is doomed to die and evil wins in spite of the slaying of the monsters. He chose a theme which would appeal to his readers and placed it against a background which would appeal even more, because it is the background of stories with which they were still familiar, representing an atti-tude to life which was not far removed from them—or from him—in time. It was his purpose to appeal to his readers and thus to strengthen them in their belief in the Christian faith. Beowulf is a compromise—an extremely clever and original one—made for religious-didactic pur-poses between heathendom and Christianity [pp. 125-26]. Kemp Malone, in Beowulf, s maintains that the poet, de-vout Christian though he is, finds much to admire in the pagan cultural tradition which, as an Englishman, he inherited from ancient Germania. It is his purpose to glorify this heroic herit-age. . . . He accomplishes his purpose by laying stress upon those things in Germanic tradition which agree with Christian-ity or at any rate do not clash seriously with the Christian faith (p. 162). - eBook - PDF

- Peter Mackay, Edna Longley, Fran Brearton(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

16 He declares that ‘the effects in Dunbar belong to something permanent in the spirit of the language’. 17 It is perhaps in Morgan’s ‘exemplification’ of aspects of medi- eval Scots poetry (itself influenced by the Old English tradition with which Morgan is engaging) that we may observe Scottish literary influence in his Beowulf. Even here, however, we should note that alongside Morgan’s appreciation of the Scottish Dunbar is his admiration for the alliterative poetry of later medieval England, notably in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl and Piers Plowman. 18 Terry Eagleton declares, characteristically, that Beowulf ‘ultimately retains its pride of place in English studies mainly due to its function, from the Victorian period forward, as the cultural tool of a troubling nationalist romance with an archetypal and mythological past’. 19 There is certainly validity to Eagleton’s perception of the eager appropriation of Beowulf for political and institutional purposes, which has gone on through- out its modern history. Tom Shippey, too, highlights the political role of Beowulf when he writes, surveying the ‘critical heritage’ of the poem, particularly in the period of what he refers to as ‘nation-forging’, ‘one has to say that the poem itself at all times appeared as a source of potential authority and power’. 20 For some modern commentators Beowulf has been tainted by association with originary myths and racial imaginings, as it has with its association with dry philological scholarship. As Kingsley Amis wrote dismissively of Beowulf not long after Morgan’s translation, Someone has told us this man was a hero. Must we then reproduce his paradigms, Trace out his rambling regress to his forbears (An instance of Old English harking-back)? 21 That was not how Morgan saw Beowulf. Morgan got beyond the philology and the racial myth to a deep appreciation of the literature. - No longer available |Learn more

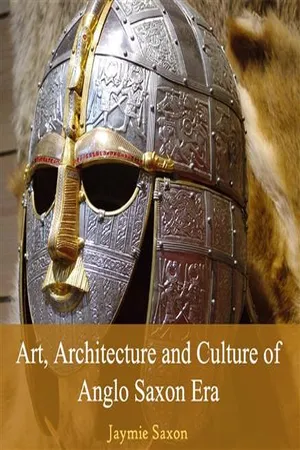

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- The English Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with the Germanic heroic past. The longest (3,182 lines), and most important, is Beowulf , which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. The poem tells the story of the legendary Geatish hero Beowulf who is the title character. The story is set in Scandinavia, in Sweden and Denmark, and the tale likewise probably is of Scandinavian origin. The story is bio-graphical and sets the tone for much of the rest of Old English poetry. It has achieved national epic status, on the same level as the Iliad, and is of interest to historians, anthropologists, literary critics, and students the world over. Beyond Beowulf, other heroic poems exist. Two heroic poems have survived in fragments: The Fight at Finnsburh , a retelling of one of the battle scenes in Beowulf (although this relation to Beowulf is much debated), and Waldere , a version of the events of the life of Walter of Aquitaine. Two other poems mention heroic figures: Widsith is believed to be very old in parts, dating back to events in the 4th century concerning Eormanric and the Goths, and contains a catalogue of names and places associated with valiant deeds. Deor is a lyric, in the style of Consolation of Philosophy , applying examples of famous heroes, including Weland and Eormanric, to the narrator's own case. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains various heroic poems inserted throughout. The earliest from 937 is called The Battle of Brunanburh , which celebrates the victory of King Athelstan over the Scots and Norse. There are five shorter poems: capture of the Five Boroughs (942); coronation of King Edgar (973); death of King Edgar (975); death of Prince Alfred (1036); and death of King Edward the Confessor (1065). The 325 line poem The Battle of Maldon celebrates Earl Byrhtnoth and his men who fell in battle against the Vikings in 991. - eBook - PDF

Primary Sources on Monsters

Demonstrare, Volume Two

- Asa Simon Mittman, Marcus Hensel, Asa Simon Mittman, Marcus Hensel(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Arc Humanities Press(Publisher)

Beowulf (INTRODUCTION, FIGHT WITH GRENDEL, THE ATTACK BY GRENDEL’S MOTHER, FIGHT WITH GRENDEL’S MOTHER, AND FIGHT WITH THE DRAGON) Translated by ROY LIUZZA Critical Introduction Beowulf is mysterious. Scholars are unsure of its date of composition (anywhere between 750 CE and 1050 CE), and its author is unknown. There is strong textual evidence that the Beowulf-poet, as he has come to be called, did not invent the story but that it existed much earlier as part of an oral tradition. However, the two great characters—Beowulf and Grendel—have no literary history that scholars have been able to discover, so they seem to have entered into English literary history ex nihilo . Finally, the poem exists in only one extant manuscript, Cotton Vitellius A.xv. Although it is now considered the crown jewel of Old English literature, Beowulf does not seem to have been particularly distinguished in its own time or even in more recent history. (It was not tran scribed and published until 1815.) Part of that lack of respect was no doubt due to the impor tance of monsters to the story. The manuscript of which it is a part contains other monsterthemed texts ( The Life of Saint Christopher and Wonders of the East , for example), but mon sters were not of great interest to the monastic centers which largely controlled the production of texts. Little changed in the poem’s early critical history: those who studied it seemed embarrassed by its focus on monsters, and it was not until 1936 that J.R.R. Tolkien (“ Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics ”) broke through the morass and made Beowulf ’s mon sters acceptable for study. The structure of the poem follows Beowulf’s fight with the three great monsters: Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the dragon.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.