Languages & Linguistics

Polari

Polari is a secret language that was used by gay men in the UK in the mid-20th century. It was a mixture of Italian, Yiddish, and Cockney rhyming slang, and was used as a way for gay men to communicate with each other without being understood by outsiders. The language has largely fallen out of use since homosexuality was decriminalized in the UK in 1967.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

4 Key excerpts on "Polari"

- eBook - PDF

Language, Sexualities and Desires

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

- Sakis Kyratzis, H. Sauntson(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Polari is mainly a lexicon derived from a variety of sources including lingua franca, the Romance-based pidgin dating from the Crusades (Hancock, 1973), rhyming slang, backslang, Italian, Occitan, Yiddish and Cant. Used by itinerant actors and showmen in the eight- eenth century, in the nineteenth century Polari had become an in-group language among theatrical and circus people and by the mid-twentieth century became associated with gay slang (cf. Cox and Fay, 1994; Baker, 2002, for a detailed discussion of the origins of Polari). By comparing some gay speech strategies through time, I seek to explore some of the social and ideological factors underlying issues of language and sexual identity from a diachronic perspective and aim to show that the last three decades have seen the emergence of a gay style that opts for equality and legitimate agency in a normatively heterosexual society. From this vantage point, I then draw on my own data and investigate social and context-related factors determining word choice by gay men in Britain and North America today. The point I wish to make, then, is that the use of gay slang has always been highly unstable, both from a diachronic and a synchronic perspective. As Harvey (1997) points out, this lack of stability seems to be a consequence of highly charged social and ideological issues which are paramount in the construction of gay identities. 120 Language, Sexualities and Desires I am interested, then, in exploring the extent to which the slang used by gay men both in terms of self- and other-identification, but also in terms of labelling experiences, has changed and why it has done so. To achieve these research aims, I employ an ethnographic method- ology of questionnaires with two groups of male gay speakers of English: gay men living in England and gay men living in North America. - eBook - ePub

Fabulosa!

The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language

- Paul Baker, Baker, Paul(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Reaktion Books(Publisher)

nanti could be combined with other words to make new Polari items.The issue is made more complex by the fact that gay men adopted Polari and ornamented it with words for concepts and various linguistic practices that were most relevant to their situation, but earlier and adjacent versions of Polari were distinctly less gay in nature, being more associated with the theatre or other forms of entertainment. A book chapter written by Ian Hancock in 1984 on Polari barely mentions the connection to gay men but instead focuses more on Polari’s link to Romance languages like Italian.1 As I’ll show in Chapter Two , there were links and overlaps between the various social groups who contributed the words that eventually became associated with gay men’s use of Polari, and we ought not to view gay men as a separate group, communicating in isolation from other people. Gay men would have held multiple social identities as well as interacting with people from a wide range of other backgrounds.Two terms I found helpful in terms of conceptualizing Polari during my research were language variety and anti-language. Language variety is a kind of general term to refer to any set of linguistic items that have a similar social distribution,2 and the term can refer just as easily to a language as to a dialect or a slang, without forcing us to be more specific. Considering that Polari was sometimes a slang but sometimes felt like it was approaching a language, the term language variety allows for definitions to be a little vague and non-committal, although it perhaps also leaves us open to accusations of fence-sitting. An anti-language on the other hand is less concerned with the issue of defining the extent to which something actually is a full language, but is more involved with considering its functions. The term anti-language refers to forms of language that are used by people who are somehow apart from mainstream society, either residing on the edges of it, perhaps frowned on in some way, or hidden away or even criminalized, with attempts from the mainstream to expel or contain them.3 - eBook - ePub

Hello Sailor!

The hidden history of gay life at sea

- Paul Baker, Jo Stanley(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

16In the early 1970s, a number of people were sensitive about existing stereotypes of gay men as effeminate queens. They wanted to move away from anything that was regarded as camp – Polari was something associated with an older generation. The images of masculine gay men, including tough sailors, coming from America were viewed as sexier in any case. As a result, Polari was gradually eroded from the face of gay culture. However, while it became less popular in the gay bars and nightclubs of the UK, on the cruise ships it continued to be used well into the 1980s. Ian, who worked as waiter and barman throughout that decade, describes it as being a private gay language that was often used to talk about or make fun of the passengers, without them understanding. ‘We’d use it to be really bitchy about the passengers, almost in front of them. We’d say something like “vada at the riah on that” about a woman’s hair, and she’d be standing right in front of us. She wouldn’t know what we were saying.’Polari is still remembered affectionately by gay seafarers who were in the Merchant Navy in the 1950s and 1960s. Some continue to use it in their everyday conversations with friends. Others who were interviewed had difficulty remembering more than a few words. In the confined circumstances of the Merchant Navy, where homosexuality could be punished, Polari was a necessary fact of life for several decades. It became one of the more creative and subversive ways that gay men both protected and expressed their sexual identities.It’s understandable that the early liberationists wanted to place distance between themselves and a period where gay people had been treated poorly by society. And it’s true that there are certain ways of using Polari that can display ambivalence, sarcasm, or downright rudeness. But in some ways it’s a shame that Polari was so quickly discarded. When a form of language dies, a way of making sense of the world dies with it. In hindsight, Polari can be remembered as an important part of gay seafaring history. Above all, it was something that was a great deal of fun because of its association with secret knowledge and shared pleasures. It gave privilege and privacy in a situation where both were scarce commodities. - eBook - ePub

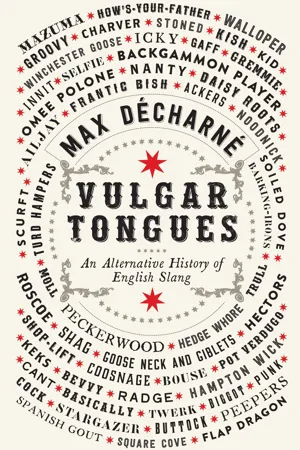

Vulgar Tongues

An Alternative History of English Slang

- Max Décharné(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Pegasus Books(Publisher)

Round the Horne (1965–8). In mid-Victorian England, however, this was simply the language of show people, with no particular same-sex associations.One punchman explained the basics to Mayhew:‘Bona parlare’ means language; name of patter. ‘Yeute munjare’ – no food. ‘Yeute lente’ – no bed. ‘Yeute bivare’ – no drink. I’ve ‘yeute munjare,’ and ‘yeute bivare,’ and, what’s worse, ‘yeute lente.’ This is better than costers’ talk, because that ain’t no slang at all, and this is a broken Italian, and much higher than the costers’ lingo. We know what o’clock it is, besides.This hybrid language was often called parlyaree, but there are many other variant spellings, such as parlare and pallary, and the more modern spelling Polari, all seemingly deriving from the Italian word parlare, to speak. Paul Barker, in his book Polari – The Lost Language of Gay Men (2002), distinguishes between Polari – the language of a certain section of the homosexual community which had its heyday between the late 1940s and the 1970s – and parlyaree, the much older language used by a variety of itinerant groups for several centuries. That a great many of the phrases which came to form part of Polari were drawn from earlier sources is clear in the dictionary which forms the latter part of the book. To call a magistrate a beak is hardly news – Sir John Fielding (1721–80), who presided over Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, was known to Londoners as the blind beak. Similarly, calling the testicles cods would not have surprised Henry VIII or any of his subjects. Kenneth Williams used Polari as a gay man in the 1940s, in his diary entry for 24 October 1947: ‘went to the matelots’ bar – met 2 marines – very charming. Bonar shamshes [the latter probably meaning smashers].’All of which recalls the dialogue between two punchmen, given by Mayhew in 1851:‘How are you getting on?’ I might say to another punchman. ‘Ultra cativa,’ he’d say. If I was doing a little, I’d say, ‘Bonar.’ Let us have a ‘shant a bivare’ – pot o’ beer. . . ‘Fielia’ is a child; ‘Homa’ is a man; ‘Dona,’ a female; ‘Charfering-homa’ – talking-man, policeman.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.