Literature

Free Verse

Free verse is a form of poetry that does not follow a specific rhyme scheme or metrical pattern. It allows poets to have more freedom in their writing, as they are not constrained by traditional poetic structures. Free verse often focuses on the natural flow of language and can vary in line length and rhythm.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Free Verse"

- eBook - PDF

- Nigel McLoughlin(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

What is of interest to creative writing students and poets is the recogni-tion that in other parts of the English-speaking world, such as Ireland and the UK, it is by no means certain that most poems are in Free Verse at all. This is because Free Verse has often been seen (incorrectly) as a foreign form, derived either from nineteenth-century French practitioners of Vers Libre , such as Rimbaud or Laforgue, or Americans such as Walt Whitman – somehow unnat-ural to the English poetic tradition. Many contemporary Irish and British poets enjoy writing in forms that tend to work better with some sort of rhyme or meter, and Free Verse needn’t have those; it is almost like walking naked. Free Verse can be quickly traced back, at least in English, to the King James Bible translation, where, for instance, the psalms sound like this: 1 Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful. 2 But his delight is in the law of the LORD; and in his law doth he medi-tate day and night. 3 And he shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatso-ever he doeth shall prosper. 4 The ungodly are not so: but are like the chaff which the wind driveth away. 5 Therefore the ungodly shall not stand in the judgment, nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous. 6 For the LORD knoweth the way of the righteous: but the way of the ungodly shall perish. 66 Todd Swift Free Verse is also used by eighteenth-century poets such as Christopher Smart who used the form in a manner that leads to it sometimes being called ‘list poetry’. The part of his long poem Jubilate Agno that readers today tend to enjoy the most is the excerpt where he praises his cat, in touching and sensitive ways that sound very contemporary to most cat lovers: For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry. - eBook - PDF

Best Words, Best Order

Essays on Poetry

- S. Dobyns(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

So far we have discussed the background of Free Verse and how it was encouraged by the social and political life of the turn of the century. Abrupt change, a flood of information, immense en- ergy-these remain common in the 1990s. Free Verse still reflects our times, although we have lost the sense of promise and enthusiasm found early in the century. On the other hand, the popularity of metered verse in the 1940s and 1980s perhaps bears out Paul Fussell's claim that metered verse is more popular during politically conservative periods. Two other aspects of Free Verse need to be stressed before continuing. First of all, Free Verse develops out of the idea of organic form-that the true poet's rhythms are always personal- an idea that we have seen evolve from Coleridge, through Whit- man and the French Symbolists and wind up as Pound's idea of absolute rhythm. The extreme effect is to make a different prosody for every poet, which is what formalist critics dislike. It keeps Free Verse from being sufficiently accountable; it makes Free Verse I 06 I Best Words, Best Order impossible to categorize and codify. Indeed, this apparent lack of accountability is a common complaint against Free Verse. The second important aspect of Free Verse is that through its diction and syntax, it often aims for verisimilitude. Although clearly artificial speech, it attempts to capture the realism and apparent spontaneity of natural speech. One of the criticisms that advocates of Free Verse make against metered verse is that stylized language is a distortion of reality. Remember that Baudelaire wrote that "the artifices of rhythm are an insurmountable obstacle to that detailed development of thoughts and expressions whose purpose is truth." 154 He was attempting to prove that the end of poetry was not truth but beauty. But later we find those values reversed; perhaps this was partly due to the nature of the society. - eBook - ePub

Verse

An Introduction to Prosody

- Charles O. Hartman(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

In Stein’s poem we saw how the lens of verse can bring into focus both the potentialities of syntax and the intensities of sound in words. These are separate properties of language which happen to be produced by the same technique of writing. Examples like this and others we’ve examined suggest one final limitation of the two-dimensional chart we tried out in the previous section. The chart tracks just two features of poetic language: the length of lines and the way their ends interact with syntax. Yet some of the ways Free Verse – when written with enough attention to all the nets available – can encourage poets to write and readers to read involve more aspects of language than these two. In the first three chapters of this book we saw how a meter abstracts and organizes a few elements out of the rich, continuous, and inclusive field of linguistic rhythm. At its best and most characteristic Free Verse takes on a relation to the details of language that is more diffuse than that of metrical verse but therefore potentially more comprehensive. Good metrical verse always urges us to look beyond the meter; good Free Verse gives us no alternative.How Free Is Free Verse?

In Chapter 2 , as we investigated the various different systems of meter that poets have used in English, we noticed that from a perspective inside one of those systems any verse that lies outside it looks nonmetrical. From the point of view of iambic meter accentual verse and syllabic verse both seem defective or incomplete. For that matter, if syllabic meter is our norm most iambic pentameter looks irregular. In this peculiar sense, almost any verse might be considered nonmetrical, and when we say that a poem is in “Free Verse” we mean that it follows no known metrical system. Yet some Free Verse seems to lie very near the boundary of some familiar metrical territory. These poems make the problem of classification messy and difficult but they may also enrich it in ways that help us both in reading the poems themselves and in thinking about how different kinds of verse are related.Dylan Thomas’s “In My Craft or Sullen Art” (1946) seems like a good example of syllabic verse. It begins:In my craft or sullen art Exercised in the still night When only the moon rages And the lovers lie abed With all their griefs in their arms, …Every line is seven syllables long and the stress patterns shift freely and clearly from one line to the next just as we saw in Thom Gunn’s “Considering the Snail” in Chapter 2 - eBook - ePub

A Prosody of Free Verse

Explorations in Rhythm

- Richard Andrews(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The present book is not intended as an easy guide to writing Free Verse. There are many on the market available through any search engine. Writing good Free Verse is as difficult as writing highly formal verse. At one end of the spectrum of composition, however, there is the ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ that will probably take no specific formal shape on the page. At the other end is the conscious fashioning of a sonnet or other poetic form. The art of Free Verse writing is to look at the first outpourings (or more minimal expressions in notes and sketches) and see if there is potential for developing a Free Verse poem, as in the previous example.In teaching Free Verse writing, there are a number of approaches. One is to provide a wide range of possibilities and then a framework for expression rather than to overprescribe Free Verse forms. Those possibilities can include the range of Free Verse styles alongside other more formal styles, both on the page and heard (and read) aloud. Experimenting with Free Verse can include imitation, as in the progymnasmata , or exercises of medieval rhetoric; the casting and recasting of material into prose, Free Verse and more formal verse forms (as demonstrated) to compare different versions; the study of a particular poet’s journey through Free Verse (e.g., Heaney); the comparison of different poets’ approaches to the degree of freedom (e.g., Ginsberg and Snyder as opposed to Stevens and Dickinson); differences between blank verse and Free Verse; and experimentation with different line lengths, verse paragraph lengths and poem lengths.Another approach is via the practice of ‘automatic’ writing. The New York City Writing project in the 1970s promoted an approach to composition which started with stimulus from the immediate environment or the recent memory. It then progressed through a memory chain where the brakes were taken off, and one image or memory was used as an automatic trigger to the next. Once the chain of ‘memories’ or instances was formed, focus on one particular link in the chain as a locus for writing often generated a stream of consciousness or more reflective current of material that might take poetic form or, at the other end of a spectrum, prose form. In terms of Free Verse, with its associations with a freer compositional sourcing of material, such an approach could be productive. At the very least, it would produce raw material that could be fashioned, in various degrees, into Free Verse. - eBook - ePub

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics

Fourth Edition

- Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, Jahan Ramazani, Paul Rouzer, Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, Jahan Ramazani, Paul Rouzer(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Content . Subject matter is not necessarily different in Free Verse from metrically regular verse. Free Verse appears to facilitate more “transparent” lang. in some poems, in which the form is hardly noticed, and this facility may have implications for the emotional effects that can be achieved. Also, the relation of form to content can be different for different types of Free Verse, although one can find exceptions to virtually any form–content pairing. Where lines are short, the reader’s attention is drawn to individual words or short phrases, and this tendency lends itself to a focus on images or on words as words. Where lines are long, the attention is drawn more to the sweep of ideas and to larger rhythmic structures; this attraction may lend itself to a grander scale of arguments and comparisons, among other differences.SeeFUTURISM , IMAGISM , LINE , METER , MODERNISM , OPEN FORM , PROJECTIVE VERSE , RHYME , SPRUNG RHYTHM , STANZA , SYLLABIC VERSE , VARIABLE FOOT , VORTICISM.T. S. Eliot, “Reflections on Vers Libre ,” New Statesman 8 (1917); E. Pound, “A Retrospect,” Pavannes and Divisions (1918); H. Monroe, “The Free Verse Movement in America,” English Journal 3 (1924); T. E. Hulme, “A Lecture on Modern Poetry,” Further Speculations (1936); Olson; D. Levertov, “Notes on Organic Form,” Poetry 106 (1965); P. Ramsey, “Free Verse: Some Steps toward Definition,” SP 65 (1968); J. Wright, Collected Poems (1971); C. Hartman, Free Verse: An Essay on Prosody (1980); R. Hass, Twentieth-Century Pleasures (1984); T. Steele, Missing Measures: Modern Poetry and the Revolt against Meter (1990); Cureton; J. Kerouac, “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” The Portable Beat Reader , ed. A. Charters (1992); S. Cushman, Fictions of Form in American Poetry (1993); A. Finch, The Ghost of Meter (1993); H. Gross and R. McDowell, Sound and Form in Modern Poetry , 2d ed. (1996); H. T. Kirby-Smith, The Origins of Free Verse (1996); D. Wesling, The Scissors of Meter (1996); E. Berry, “The Free Verse Spectrum,” CE 59 (1997); G. B. Cooper, Mysterious Music: Rhythm and Free Verse (1998); C. Beyers, A History of Free Verse (2001).G. B. COOPERFREIE RHYTHMEN. In Ger., this term refers to unrhymed, metrically irregular, nonstrophic verse lines of varying length. These lines can usually be distinguished from rhythmical prose not only by their visual arrangement on the page but by a tendency toward nearly equal intervals between stressed syllables, as well as phonological and rhythmic correspondences between lines. Freie Rhythmen represent the only major formal innovation that Ger. lit. provided to world lit. in the 18th c. Introduced by F. G. Klopstock in the 1750s (e.g., “Dem Allgegenwärtigen,” 1758; “Frühlingsfeier,” 1759) as a conscious revolt against the restraints imposed on Ger. poetry by Martin Opitz in the 17th c., freie Rhythmen are particularly appropriate as a medium for the free, unrestrained expression of feelings typical of the age of *sentimentality (Empfindsamkeit - eBook - PDF

- Steven Earnshaw(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

When people think of metre, line and stanza as carapaces, shapes into which language must be forced, where it sits the way an invertebrate’s flesh is contained in a shell, they lose connection with the rhythmic roots of speech. When they write Free Verse and think of them-selves as cracking the old moulds in which words used to be straitjacketed, they overlook the 202 The Handbook of Creative Writing pattern-building facility which drives all verse from nursery rhymes to renga, from the ballad to the calligramme. In other words they assume that a metrical writer has divided structure from content, whereas their proper practice is to unite these in a unique event. A writer who managed to express some of the functions of form succinctly was, perhaps unexpectedly, Robert Louis Stevenson. Writing in a period when conventional assump-tions about verse were being challenged by French prose poems like those of Baudelaire, and America’s more rhetoric-driven structures, typified by Whitman, and being familiar with the experiments in Free Verse of his close friend W. E. Henley, Stevenson showed himself sympathetic to both innovation and tradition: Verse may be rhythmical; it may be merely alliterative; it may, like the French, depend wholly on the (quasi) regular recurrence of the rhyme; or, like the Hebrew, it may consist in the strangely fanciful device of repeating the same idea. It does not matter on what principle the law is based, so it be a law. It may be pure convention; it may have no inherent beauty; all that we have a right to ask of any prosody is, that it shall lay down a pattern for the writer, and that what it lays down shall be neither too easy nor too hard. (Stevenson 1905) This is admirably even-handed, and still applicable today if slightly incomplete, as is what he goes on to say about line: Hence . . . there follows the peculiar greatness of the true versifier . - eBook - PDF

How to Write About Poetry

A Pocket Guide

- Brendan Cooper(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

Here, of course, the very same words are being used. But arranged like this – as Free Verse, with no regularity to each line – the feel of the sentence is different. There is a much greater sense of movement, of instability, with no punctuation at the end of the lines (technically described as enjambment), and the length and rhythm of each line varying. This example gives some sense of the kinds of effect Free Verse can create. It would be easy to make a simple claim that regular metre suggests harmony, with The Challenge of Poetic Form 53 the irregularity of Free Verse suggesting disharmony – but things are, of course, not quite so straightforward as that. Free Verse does not always connote disharmony, by any means – but the varied patterns and rhythms of Free Verse do open up a sense of dynamic change, of unpre- dictability and unevenness and dissonance, that cannot be captured within the constraints of a regular metrical framework. An excellent example of how Free Verse can be effec- tively used is “Praise Song for my Mother”, by the Guyanese poet Grace Nichols. This poem, in which the speaker endeavours to highlight the various inspirational quali- ties of her mother, begins as follows: You were water to me deep and bold and fathoming The link of the mother-figure to “water” provides her here with essential, life-giving qualities. Throughout the poem, very little punctuation is used, creating a primal, elemental quality that helps to complement the depth and the vital- ity of the bond between mother and child. In a poem of celebration such as this one, the varying rhythms to each line, and the varying line lengths, do not seem to create disharmony so much as a feeling of simplicity and natu- ralness. Though there is a background sadness, too – the speaker addresses her mother in the past tense throughout the poem (“You were […] you were […] you were”), imply- ing that the mother has died – the overall tone is one of - eBook - ePub

- Bliss Perry(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

5. Discovery and RediscoveryIt is not pretended that the four types of Free Verse which have been illustrated are marked by clear-cut generic differences. They shade into one another. But they are all based upon a common sensitiveness to the effects of rhythmic prose, a common restlessness under what is felt to be the restraint of metre and rhyme, and a common endeavor to break down the conventional barrier which separates the characteristic beauty of prose speech from the characteristic beauty of verse. In this endeavor to obliterate boundary lines, to secure in one art the effects hitherto supposed to be the peculiar property of another, Free Verse is only one more evidence of the widespread "confusion of the genres" which marks contemporary artistic effort. It is possible, with the classicists, to condemn outright this blurring of values. [Footnote: See, for instance, Irving Babbitt, The New Laokoon. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910.] One may legitimately maintain, with Edith Wyatt, that the traditional methods of English verse are to the true artist not oppressions but liberations. She calls it "a fallacious idea that all individual and all realistic expression in poetry is annulled by the presence of distinctive musical discernment, by the movement of rhyme with its keen heightening of the impulse of rhythm, by the word-shadows of assonance, by harmonies, overtones and the still beat of ordered time, subconsciously perceived but precise as the sense of the symphony leader's flying baton. To readers, to writers for whom the tonal quality of every language is an intrinsic value these faculties of poetry serve not at all as cramping oppressions, but as great liberations for the communication of truth." [Footnote: New Republic - eBook - PDF

- John Singleton, Mary Luckhurst, John Singleton, Mary Luckhurst(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

The lines, and the groups, may be regular in one or another way, as in limericks and sonnets; or they may be irregular, creating a new form 164 WRITING VERSE 165 unique to that poem: but in all cases there is a form, so again the choice is not whether to have a form, but whether you attend to the form. Poetry has varied enormously over time (as you can see by paging through the Norton Anthology), and because people have often been taught poetry narrowly at school there are common misconceptions about 'what poetry is'. Before the twentieth century most poetry in English was written in regu-lar metres (or patterns of stress), so that each line has a similar rhythm; and in prescribed forms, so all the lines are either of the same length, or vary in a regular way. Poems of this kind often have a regular pattern of end-rhymes (called the rhyme scheme): but this does not mean that 'all poems rhyme', nor that 'if it rhymes it's a poem'; and in the twentieth century (especially since T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land [1922]: N1236) Free Verse (where the metrical pattern varies from line to line) and open form (where the line lengths and rhyme scheme are ir-regular) have become increasingly popular. There is still metre, and form: but they are freed from preset rules and limits. You may want to write more traditional poetry (and many poets, like Tony Harrison, have continued to use regular metres and forms), or you may want to experiment with Free Verse, but in either case you will need to understand metre and form, to make them regular or to control their irregularities. Metre and form are very general terms, and each can be subdivided in many ways (some of which are explored in the Workshop Writing and Writing On sections). - No longer available |Learn more

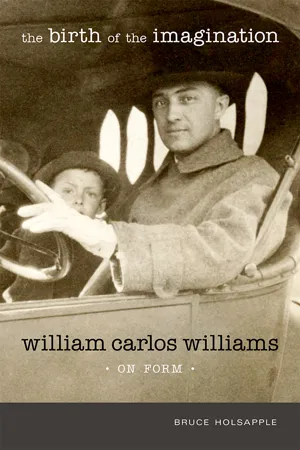

The Birth of the Imagination

William Carlos Williams on Form

- Bruce Holsapple(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of New Mexico Press(Publisher)

But holding that move in abeyance, there are several telescoping claims made, all of which need weighing. They run some-thing like this: As argued in Spring and All , poetry is formal and writing poetry involves de facto the invention of new forms. Modernist poetry—vers libre—is at an impasse as regards its internal form, its rhythmic properties. But changes to English as it evolved into an American vernacular, in pronuncia-tion, stress, and melody, have altered our unit of verse measurement, the foot, such that using that older measure no longer has a “rhythmical power of inclu-sion.” Williams proposes finding a new, internal form in the vernacular. The new line, as he imagines it, would be timed by the musical phrase rather than the “old time rigidities” of the metronome, exactly as Pound proclaimed with imagism in 1913, then recast in musical terms with Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony in 1924. Musical phrasing would be shaped by properties inherent in American speech. Williams soon finds support for his claims in H. L. Mencken’s The American Language . Twenty-five years later, in the 1957 interviews with Edith Heal, Williams talked of his Complete Collected Poems in 1938—seven years forward from the manifesto—as providing him with “the whole picture,” a chance to appraise all he “had gone through technically to learn about the making of a poem.” He recounted learning to organize a poem into lines: 273 the verse line ● The greatest problem was that I didn’t know how to divide a poem into what perhaps my lyrical sense wanted. Free Verse was not the answer. From the beginning I knew that the American language must shape the pattern; later I rejected the word language and spoke of the American idiom—this was a better word than language, less academic, more identified with speech. - eBook - PDF

- Regna Darnell, Judith T. Irvine, Richard Handler, Regna Darnell, Judith T. Irvine, Richard Handler(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

Much of the misunder-standing of the freer forms may well be due to sheer inability to think, or rather image, in purely auditory terms. Had poetry remained a purely oral art, unhampered by the necessity of expressing itself through visual symbols, it might, perhaps, have had a more rapid and varied formal development. At any rate, there is little doubt that the modern develop-ments in poetic form would be more rapidly assimilated by the poetry-loving public. Most people who have thought seriously of the matter at all would admit that our poetic notation is far from giving a just notion of the artist's intentions. As long as metric patterns are conventionally ac-cepted as the groundwork of poetry in its formal aspect, it may be that 944 III Culture no great harm results. It is when subtler and less habitual prosodic features need to be given expression that difficulties arise. Free Verse undoubtedly suffers from this imperfection of the written medium. Re-tardations and accelerations of tempo, pauses, and time units are merely implied. It is far from unthinkable that verse may ultimately be driven to introduce new notational features, particularly such as relate to time. It is a pity, for instance, that empty time units, in other words pauses, which sometimes have a genuine metrical significance, cannot be di-rectly indicated. In Frost's lines: Retard the sun with gentle mist; Enchant the land with amethyst. Slow, slow! is not the last line to be scanned Μ - [u - u] -[u -]? The silent syllables are enclosed in brackets. What would music be with-out its rests, or mathematics without a zero? Editorial Note Originally published in Journal of English and Germanic Philology 20, 213—228. Reprinted by permission of the University of Illinois Press. A shortened version of this paper was prepared by Sapir, under the title What is Verse?, but was never published. Note 1. The Dial, Jan. 17, 1918.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.