Literature

Unreliable Narrator

An unreliable narrator is a character in a story whose credibility is questionable. They may intentionally or unintentionally misrepresent events, characters, or their own thoughts and feelings. This technique is often used in literature to create suspense, ambiguity, and to challenge the reader's assumptions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Unreliable Narrator"

- eBook - PDF

The Dynamics of Narrative Form

Studies in Anglo-American Narratology

- John Pier(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

Significantly, there are theories of unre-liable narration 9 , as well as at least one collection of essays on the issue 10 plus a monograph on the unreliable first-person narrator 11 , whereas their counterparts do not appear to exist. In this article, the concepts of reli-ability and unreliability in narrative will be jointly entertained by taking into account their pronominal affiliations. A succinct definition of the Unreliable Narrator is provided by Nün-ning: Unreliable Narrators are those whose perspective is in contradiction with the value and norm system of the whole text or with that of the read-er 12 . Hence, unreliability in narration emerges when discrepancies arise in the text or, more importantly, divergences between the narrator's and the reader's views. However, Nünning also tends to obliterate the distinc-tion between narrative reliability and unreliability by proposing a cogni-tive theory in which narration is unreliable when compared to the read-er's or critic's preexisting conceptual knowledge of the world and to his or her (usually unacknowledged) frames of reference 13 . The implication here is that, since all readings of texts are subjective, the distinction be-tween reliable and unreliable narration expresses an outmoded objectivist ideal. In like manner, Kathleen Wall argues: The standard definitions of an Unreliable Narrator presuppose a reliable counterpart who is the 'ra-tional, self-present subject of humanism' 14 . Sketching the ordinarily un-reliable narrator, whose world view, predispositions, ignorance, or absent-mindedness determine in some way what he or she notices, and how he or she interprets certain situations, Wall claims that [t]o some degree, all narrators, like all human beings, fall into this category 15 . - eBook - PDF

- James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Most definitions in the wake of Booth have emphasized that unreli-ability consists of a moral distance between the norms of the implied or real author and those articulated by the narrator. But other theorists have pointed out that what is at stake is not a question of moral norms but of the veracity of the account a narrator gives. Thus Rimmon-Kenan’s ([1983] 2003: 100) definition leaves open whether unreliability is to be gauged in comparison to the accuracy of the narrator’s account of the story or to the soundness of his or her commentary and judgments: ‘‘An Unreliable Narrator [ . . . ] is one whose rendering of the story and/or commentary on it the reader has reasons to suspect.’’ The ‘‘and/or’’ construction sounds very open and flexible but actually it is a bit too nonchalant. Most would agree that it does make a difference whether we have an ethically or morally deviant narrator who provides a sober and factually veracious account of the most egregious or horrible events, which, from his point of view, are hardly noteworthy, or a ‘‘normal’’ narrator who is just a bit slow on the uptake and whose flawed interpretations of what is going on reveal that he or she is a benighted fool. It is thus unclear whether unreliability is primarily a matter of misrepresenting the events or facts of the story or whether it results from the narrator’s deficient understanding, dubious judgments, or flawed interpretations. Aware of these problems, some narrative theorists have suggested terminological refinements and typological distinctions. Lanser (1981: 170–1) was among the first to suggest that one should distinguish between an Unreliable Narrator, that is, a narrator whose rendering of the story the reader has reasons to suspect, and an untrustworthy one, that is, a narrator whose commentary does not accord with conventional notions of sound judgment. - Elke D'hoker, Gunther Martens, Elke D'hoker, Gunther Martens(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

A LICE J EDLI KOVÁ (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic) An Unreliable Narrator in an Unreliable World. Negotiating between Rhetorical Narratology, Cognitive Studies and Possible Worlds Theory 1. Introduction Unreliable narration is generally considered as one of the typical devices of modern and postmodern literature, connected as it is with the transfor-mation of traditional social schemes and the re-evaluation of the concept of the individual in the twentieth century. But is unreliable narration in-deed restricted to modern literature? Or is it possible to discern it in pre-modern narratives without falling into the error of ahistorical misreading? To this temporal query, we might also add a spatial one: to what extent are unreliable narratives distributed across different nations and cultures? And how do we avoid mistaking cultural diversities for aspects of unreliable narration? Finally, does unreliability belong to the properties of a given narrative or is it a mere strategy for naturalizing a text? These questions have preoccupied many narratologists since Booth and have lead to a reconceptualisation of unreliability e.g. in the context of cognitive narra-tology. Most theories, however, share the view that unreliable narration is a phenomenon connected with character narration (i.e. first-person narrator) and they rarely question the ‘authority’ of the omniscient third-person nar-rator. Wayne C. Booth famously located the phenomenon of unreliability within the structure of the narrative text and described it as a set of incon-sistencies and contradictions resulting from the confrontation of the ac-tions and speech of a personal narrator with the norms of the work, per-sonified in the implied author. The idea of the implied author – which Booth in a later essay called an “authorial better self” 1 –includes the role ––––––––––––– 1 Booth (2005).- eBook - ePub

- Astrid Erll, Roy Sommer(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

American Psycho (1991) – a book I still had to buy under the counter in the 1990s because it was banned from display in the bookshops? Unreliability, to put it bluntly, has become banal and boring. Once it was a literary device that mirrored unreliability in real-life contexts, forcing us to come to terms with ambiguous messages or positions. But this is no longer the case. We may, then, justly proclaim the ‘death’ of the Unreliable Narrator.Thesis 4: Narrative unreliability in literature today only ‘stages’ unreliable narration as a literary convention

The recognition that narrative unreliability has lost its former impetus and destabilizing potential does not, of course, mean that writers will stop using the technique. A glance at contemporary novels proves that, on a purely formal level, Unreliable Narrators still exist (although their numbers are significantly diminishing). However, instead of naturalizing such narrators in the terms proposed by classical theories of unreliable narration, twenty-first-century authors and readers will likely activate different frames of reference, for instance aesthetic or dramaturgical ones.Ansgar Nünning (2008, 58 ) has acknowledged this same mechanism at work at the inception of the history of unreliable narration. Although the narrator of William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. (1844) “is a paradigmatic Unreliable Narrator,” Nünning claims that the novel itself should not be considered unreliable because it “does not call into doubt the notion that human beings are principally [sic] taken to be capable of providing veracious accounts of events and of others” (Nünning 2008 , 59). This comes down to the realization that, in order to be read (and, indeed, written) on the basis of cognitive frames that lead to the ascription of unreliability in the narrator, the novel needs to create (in this case epistemological) ambiguity. The narrative in Barry Lyndon , however, “does not call into doubt” the idea that “veracious accounts of events and of others” are possible; it does not fulfill the metafunction of ambiguity.This is also true for the use of unreliability in the twenty-first century. The narrators of Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones (2006) or Martin Amis’s The Zone of Interest - eBook - PDF

Untamable Texts

Literary Studies and Narrative Theory in the Books of Samuel

- Greger Andersson(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- T&T Clark(Publisher)

But how do we know whether a feature is intended or not? My tentative answer is this: by asking whether a certain technique has a function in relation to our apprehension of the sense-governing intent of a certain piece of narrative communi-cation. An Unreliable Narrator is, for example, a device that is supposed to produce a certain effect. The reader comes gradually to realize that the words of the narrator—who in general (if not always) is a character in the story—deviates from the norm of the narrative. This is something quite different from the suggestions that the narrator is unreliable if there are contradictions or mistakes in a text. 4.1.8. Storytelling and the Teller I will in this, the nal, section about the biblical narrator relate the dis-cussion in the foregoing sections to the hypothesis that many biblical narratives are storytelling (in the sense I use the term). Let us say that a reader who turns to the Bible for the rst time happens to start with this passage: 1 In the spring of the year, the time when kings go out to battle, David sent Joab with his ofcers and all Israel with him; they ravaged the Ammon-ites, and besieged Rabbah. But David remained at Jerusalem. 2 It happened, late one afternoon, when David rose from his couch and was walking about on the roof of the king’s house, that he saw from the roof a woman bathing; the woman was very beautiful. 3 David sent some-one to inquire about the woman. It was reported, “This is Bathsheba daughter of Eliam, the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” 4 So David sent messen-gers to get her, and she came to him, and he lay with her. (Now she was purifying herself after her period.) Then she returned to her house. 5 The woman conceived; and she sent and told David, “I am pregnant.” (2 Sam 11:1–5) The rst question such a reader would pose, in my opinion, concerns the sense-governing intent of this narrative. - eBook - ePub

Unreliable Narration and Trustworthiness

Intermedial and Interdisciplinary Perspectives

- Vera Nünning(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

There are elements common to non-fictional journalism and fictional narrative: Both have a narrator who communicates the story in a special way to an audience. The reliability and credibility of the narrator and the narrative not only depend on text-immanent, e.g. structural and semantic characteristics, but also and mainly on external and contextual characteristics and thereby mainly on the recipient, his experience, his knowledge, his system of norms and values and his knowledge of literary conventions (Nünning 1998). Ansgar Nünning modifies and transfers the findings of cognitive narratology related to the phenomenon of unreliable narration in fictional texts where the main focus of his research is to non-fictional genres (Nünning/Allrath 2005). Based on that the most important differences are:- – Fictional unreliable narration often is a rhetorical and/or aesthetic strategy. “In non-fictional narratives the lack of believability or credibility of a narrator is not an assessment the author intends the reader to make” (ibid.: 184).

- – In contrast to recipients of fictional narration, readers of non- fictional stories have the opportunity to add, to modify or to question the credibility of a narrator using additional information (ibid.).

- – While the author of a fictional narration always establishes a narrator, in authentic communication “a narrator usually is identical with the creator of the narrative, meaning that a non-fictional narrator only uses strategies to undermine the credibility of what he has said consciously under exceptional circumstances” (ibid.: 185). In contrast, the narrator of real stories will always try to strengthen his credibility.

- – The “social identity” of an actor is important in fictional as well as in non-fictional narration. For the former, it is important that there are no contradictions between the narrator’s description and his value judgements, but a non-fictional narrator can be identified by other characteristics. Physical characteristics like appearance, clothes, body language, mimicry and gestures are key factors in audiovisual media for the evaluation of the credibility and trust of a communicator (ibid.: 186–187).

- eBook - PDF

How Literary Worlds Are Shaped

A Comparative Poetics of Literary Imagination

- Bo Pettersson(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

In literary theory the study of unreliability started out with a fairly specific focus but has gone on to broaden its scope. Wayne C. Booth (1961/1983: 158) launched the discussion by analysing narrators speaking or acting against “ the norms of the work (which is to say, the implied author ’ s norms) ” . In keeping with the text-immanent study that characterized much of literary studies in the late twentieth century (see Pettersson 2005a), the subsequent focus was on nar-rators and their relation to their implied authors as well as for some, including Booth and his most illustrious follower James Phelan, by implication the actual flesh-and-blood authors who created them. As far as I know, the only monograph on fictional unreliability so far is that of William Riggan (1981), who presented four categories of unreliable first-person narrators: pícaros (e. g. Apuleius ’ The Golden Ass , Defoe ’ s Moll Flanders ), clowns (Sterne ’ s Tristram Shandy , Nabokov ’ s Lolita ), ⁴ madmen (Gogol ’ s “ Diary of a Madman ” , many of Poe ’ s stories) and naifs (Twain ’ s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , ⁵ Salinger ’ s The Catcher in the Rye ). A somewhat broader typology, but still largely a textual one has more recently been presented by Per Krogh Hansen (2005). It consists of four potentially inter-related types of unreliability, depending on whether it is “ marked in the narra-tor ’ s discourse [intranarrational], by other narrators relating [internarrational], by virtue of the type the narrator as character is modelled upon [intertextual; cf. Riggan ’ s types], and in relation to the knowledge the reader brings to the text [extra-textual] ” (Hansen 2005: 302). A third typology can be found in Tamar Yacobi ’ s (2000: 713) important writings spanning over three decades ad-vancing five integrative mechanisms of interpretation that “ account for apparent On the parsing of deception in relation to the suspension of disbelief see O ’ Sullivan ( : ). - eBook - ePub

- Katherine Thomson-Jones(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

Last Year at Marienbad (1961), where the voice-over narrator instructs someone to show us a different location for the event being related. Who could it be that the voice-over narrator instructs? If it must be someone inside the fiction who is charged with showing us what happens, this sounds a lot like the cinematic narrator. Examples like this show us that we need to think about when it is useful for our making sense of film narration to posit a cinematic narrator. This will depend on the particular narration and whether it is constructed so as to imply the mediation of an implicit visual guide.WHAT IS IT FOR A FILM’S NARRATION TO BE UNRELIABLE?

Another reason why it is important to decide whether films must always have narrators is so that we can understand narrative unreliability in film. If, when watching a film, we have the sense that we’re not being told the whole or the true story of events, say by a character narrator, then we are most likely identifying narrative unreliability. The standard definition of narrative unreliability in literary theory invokes a narrator who intends to have us believe something other than what the (implied) author intends to be true in the fiction. Given the discussion we have just had about whether every film has a narrator, the interesting question is whether you can have narrative unreliability without a narrator. If you can, then the possibility of narrative unreliability cannot be assumed to support any necessary claims about the narrator.Even if it is true that in literature unreliable narration is always the work of an Unreliable Narrator, this does not automatically account for the case of film. This is because film, in its capacity both to tell and to show a story, can be unreliable in unique and distinctive ways. Two-track unreliability can take different forms, depending on how a particular film sets up a tension between verbal and visual narration. In more unusual cases, even though verbal narration and visual narration are uniformly consistent, a film may exhibit a subtle form of global unreliability. This kind of unreliability is revealed by ambiguity in the interpretation of a film and can be described without reference to a narrator. - eBook - ePub

- Anita Tarr(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs (1989), a picturebook by Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith, is narrated by the Big Bad Wolf, who argues that the so-called crimes he has committed are the result of his trying to bake a cake for his grandmother while suffering from a cold. He needed a cup of sugar, so he traveled to his neighbors’ houses, where his timely sneezes destroyed two flimsy houses and killed their porcine owners, which he could not help eating (it would be like passing up a cheeseburger, he says). After the third pig’s brick house stood up to his sneeze, he was arrested, his carnage at an end. Still, he pleads innocent: “I was framed,” he tells readers, speaking from his jail cell. He then very politely asks if anyone would be willing to lend him a cup of sugar. Yikes! Although dressed nappily in a bow tie, displaying harmless small teeth, and showing off high-toned manners, the Wolf’s disguise will not fool even very young children. They know that he is lying. This Big Bad Wolf, then, is perhaps a child reader’s first introduction to an Unreliable Narrator.This chapter explores how specific children’s and Young Adult literature employ an Unreliable Narrator—that is, a narrator who is either intentionally or unintentionally not telling the whole story, a story that is “off-kilter” (Phelan, Somebody 231). First described by Wayne C. Booth in The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961 [1983]), the term Unreliable Narrator has been subject to much scrutiny, and scholarship is rich with analyses of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), and, more recently, Charlotte Brontë’s ]ane Eyre (1847).1 Because child readers are more likely to be novice readers, they will not have the experience with fictional devices to discern that a first-person narrator is trying to hoodwink them; thus, Unreliable Narrators are rare in children’s fiction but more common in Young Adult fiction, as authors assume some degree of sophistication from their readers. This chapter will apply recent narratological theories regarding unreliable narration to specific novels, including Gennifer Choldenko’s Notes from a Liar and Her Dog (2001), Marcus Zusak’s The Book Thief (2005), Justine Larbelestier’s Liar (2009), and J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951). However, most of my discussion will center on Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (2003) and China Miéville’s Embassytown (2011).Unreliable Narrators in Children’s and Young Adult Novels

Narrative theorists have delighted in creating intricate taxonomies to define types of Unreliable Narrators. I am using James Phelan’s idea that reliable narration and unreliable narration are at opposite ends of a spectrum, acting as bookends for more nuanced types. The basic formulation is deciding the distance between the (implied) author, (implied) narrator, and actual audience. In reliable narration, the author, narrator, and audience are mostly aligned, creating a bonding effect, a trusting relationship. In unreliable narration, the distance is greater, creating estrangement. There are myriad subcategories, depending upon whether the narrator is misreporting, misinterpreting, and/or misevaluating. There is one point of Phelan’s theories that is especially important: he is considering only adult readers and thus puts equal onus on the narrator and the reader for the responsibility of discerning the reliability of the narrative (“Reliable” 90). There is no accounting for naïve readers and their relationship with a challenging text. - eBook - PDF

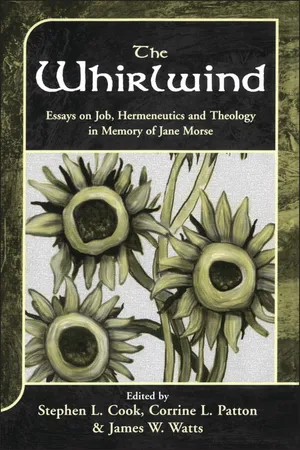

The Whirlwind

Essays on Job, Hermeneutics and Theology in Memory of Jane Morse

- Stephen L. Cook, Corrine L. Patton, James W. Watts(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Sheffield Academic Press(Publisher)

THE Unreliable Narrator OF JOB* James W. Watts One of the most obviously artificial devices of the storyteller is the trick of going beneath the surface of the action to obtain a reliable view of a character's mind and heart. Whatever our ideas may be about the natural way to tell a story, artifice is unmistakably present whenever the author tells us what no one in so-called real life could possibly know. In life we never know anyone but ourselves by thoroughly reliable internal signs, and most of us achieve an all too partial view even of ourselves. It is in a way strange, then, that in literature from the very beginning we have been told motives directly and authoritatively without being forced to rely on those shaky inferences about other men which we cannot avoid in our own lives. 'There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright, one that feared God, and eschewed evil'. With one stroke the unknown author has given us a kind of information never obtained about real people, even about our most intimate friends. Yet it is information that we must accept without question if we are to grasp the story that is to follow. In life if a friend confided his view that his friend was 'perfect and upright', we would accept the information with qualifications imposed by our knowledge of the speaker's character or of the general fallibility of mankind. We could never trust even the most reliable of witnesses as completely as we trust the author of the opening statement about Job... This form of artificial authority has been present in most narrative until recent times. 1 These are the opening paragraphs of The Rhetoric of Fiction, Wayne Booth's influential study of narrative style.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.