Mathematics

Algebraic Representation

Algebraic representation involves expressing mathematical relationships and patterns using symbols and variables. It allows for the generalization of mathematical concepts and the manipulation of equations to solve problems. In algebraic representation, equations, inequalities, and functions are used to describe and analyze mathematical situations.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Algebraic Representation"

- eBook - ePub

- Wayne A. Wickelgren(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

10Topics in Mathematical Representation

As stated in Chapter 2, problems contain information concerning givens, actions, and goals. The first and most basic step in problem solving is to represent this information in either symbolic or diagrammatic form. Symbolic form refers to the expression of information in words, letters, numbers, mathematical symbols, symbolic logic notation, and so on. Diagrammatic form refers to the expression of information by a collection of points, lines, angles, figures, directed lines (vectors), matrices, plots of functions, graphs, and the like. Often the same information should be represented using a variety of symbolic or diagrammatic notations. In fact, diagrammatic representation is generally labeled; for example, points, lines, and cells in a matrix have symbols attached to them in the diagram. Of course, problems are stated originally in some form, often relying heavily upon verbal language. The first step in solving such a problem is to translate from the representation given explicitly or implicitly in the original statement of the problem to a more adequate representation.This chapter is concerned with selected topics in the mathematical or precise representation of information in problems. Although precise representation of the information in a problem is the first step to take in trying to solve a problem, I deferred discussing this important topic to this late chapter of the book for two reasons.First, although some general statements can be made about the representation of information in a large variety of problems, most of the principles of representation are specific to particular problem areas. Effective representation for problems from some area of mathematics, science, or engineering depends upon knowing centuries of conceptual development in the relevant areas of mathematics, science, and engineering. I doubt that mankind will ever develop a general method for determining what are the useful concepts to define in any particular area. Certainly, no such general principles of how to define good concepts are presented in this book. The best I can do is to present those types of concepts and the principles for representing them that have proved the most useful in a wide variety of areas of formal problem solving. This is what is done in the present chapter, without any claim to completeness (which would be preposterous) and with only minimal claim to logical organization of the concepts and the principles of mathematical representation. - eBook - ePub

- James J. Kaput, David W. Carraher, Maria L. Blanton, James J. Kaput, David W. Carraher, Maria L. Blanton(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Children’s work with and understanding of notations plays a pivotal role in their emerging algebraic knowledge. Various representational systems serve to provide an entryway into the bigger and generalizable ideas of the mathematics. Children can use mathematical notations not only to register what they understand, but also to structure their thinking. That is, notations can help further children’s thinking (Brizuela, 2004). A variety of representational systems (e.g., tabular, graphical, verbal, and iconic) augment mathematical understanding, allowing children’s algebraic thinking to continue to emerge through the consideration and comparison of multiple structures. This facility of connecting ideas among systems allows children to make inferences about mathematical attributes and their various manifestations that they might otherwise not have made.Much of our early algebra research has focused on the issue of introducing various mathematical symbols in meaningful ways. Our approach relies on introducing new notations as variations on students’ spontaneous notations (Brizuela & Lara-Roth, 2002; Carraher, Schliemann, & Brizuela, 2001). Although symbolic reasoning is traditionally associated with the syntactical manipulation of written expressions, other systems of representation play a role, highlighting otherwise hidden mathematical attributes. When meaningfully structured, these additional notations bring new understandings and corroborate previously learned mathematical information.Researchers and policy guidelines have focused on the importance of multiple representational systems, a focus that has carried over to early algebra research (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2000). However, a dynamic relationship among representational systems goes beyond the recommendations made by guidelines. Different representations not only “illuminate different aspects of a complex concept or relationship,” as explained in the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) policy guidelines (p. 68), but also shed light on new understandings through the consideration and comparison across representations. Conventional notations help extend thinking (Cobb, 2000; Lerner & Sadovsky, 1994; Vygotsky, 1978), but if they are introduced without understanding, students may display premature formalization (Piaget, 1964). For these reasons, students need to be introduced to mathematical notations in ways that make sense to them. - eBook - ePub

Empowering Mathematics Learners: Yearbook 2017, Association Of Mathematics Educators

Yearbook 2017, Association of Mathematics Educators

- Berinderjeet Kaur, Ngan Hoe Lee;;;(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

In order to develop students’ mathematics thinking repertoire for today’s learning, Devlin (2014) suggests that, as educators, less attention should be on procedural learning that focused on computational skills and procedures and more on guiding students “learn how to learn” and develop “a good conceptual understanding of mathematics, its power, its scope, when and how it can be applied, and its limitations” (p. 21). A key to achieving this focus is for teachers to pay more attention to student’s voice by listening to them diligently and value their contribution. In other words, to facilitate this, teachers need to be provided with knowledge and examples of thinking tasks activities that showcase how they may encourage the development of mathematical thinking among learners during mathematics lessons. We are of the view that these thinking activities can be developed through deliberate use of representations during mathematics lessons.2The Use of Mathematical Representations as a Tool (to Develop Mathematical Thinking)What are representations? “A representation is a configuration that can represent something else in some manner” (Goldin, 2002, p. 208). Historically people have developed and used representations in order to interpret, remember or communicate their experiences. From early cave dwellers to the Egyptians hieroglyphics and the Babylonian numeration systems, we see the use of representations in the expression and communication of ideas.2.1Types of mathematical representationsNumerous research studies and position papers have been written on this subject over the years. Lesh, Landau, and Hamilton (1983) found five kinds of representations that are useful for mathematical understanding: (a) real life experiences, (b) manipulative models, (c) pictures or diagrams, (d) spoken words, and (e) written symbols. Other have specifically looked at representation used to understand mathematics (Goldin, 2003; Goldin & Shteingold, 2001; Lesh, Landau, & Hamilton, 1983; Lesh, Post, & Behr, 1987). In many cases access to abstract mathematical ideas and concepts can only be obtained through the representations of those ideas and concepts through diagrams, charts and symbols (Kilpatrick, Swafford, & Findell, 2001). According to Bruner people represent ideas in three distinct forms, (a) through actions - enactive), (b) through pictures or diagrams - iconic and, (c) through words and language - symbolic. (Bruner, 1966).Goldin and Shteingold (2001) suggest a useful way of classifying representations. They suggest two systems of representation - external systems of representation and internal systems of representation. External representations in mathematical context refers to quantitative cognitive tasks that are usually quantified or measurable such as computing the four fundamental operations (add, subtract, multiply and divide) with paper and pencil, drawing a graph, writing algebraic expression, communicating verbal mathematical language and etc. where these cognitive task has been built over a period of time. On the other hand, internal representation refers to qualitative cognitive tasks that goes in the mind of an individual with the goal of giving meaning to it. Examples of internal representation includes personal notation systems, natural language, visual imagery, and problem-solving strategies (Salkind, 2007). These two types of representation by Goldin and Shteingold are of great relevance in the context of this chapter and will be discuss them in more depth in sections 2.2 and 2.3 - eBook - PDF

Teaching and Learning Mathematics

A Teacher's Guide to Recent Research and Its Application

- Marilyn Nickson(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

Algebra: the Transition from Arithmetic 125 Symbolization 1. There is evidence of considerable rigidity in children's interpretation of symbols when they adopt stereotypical views. This applies to literal symbols such as x and y and to '=' which, from a procedural perspective, they take to mean that a single result is expected. 2. The research suggests that for structural understanding of algebra, children have to come to see algebraic expressions as entities or objects. For this to happen, they must focus on the whole of the expression which is to be 'used' as an entity. This may cause confusion with the opposite situation that prevails in solving word problems and emphasis is laid on the part-whole approach and a single answer is expected. 3. Children have a stereotypical view of the way in which they expect an equation to be represented and will carry out unnecessary processes to try to get an equation into that format. 4. There is an indication of a link between children's ability to process written and spoken language (i.e. literacy) with their ability to process symbols in a mathe-matical context. While more research needs to be done in this area, it may be that making a link between their 'symbol awareness' in the context of written language and 'symbol awareness' in the context of mathematics, could lead to identifying possible weaknesses in their understanding and how they may be overcome. Proof 1. The evidence suggests that pupils at secondary school level may have a reason-able notion of what constitutes a mathematical proof. However, even where this is the case, they still value explanatory arguments rather than those of an algebraic nature. The algebra needed to produce a proof appears to be difficult for them when it comes to communicating and explaining the proof and, in par-ticular, in translating a verbal proof into symbols. - eBook - ePub

The Learning and Teaching of Algebra

Ideas, Insights and Activities

- Abraham Arcavi, Paul Drijvers, Kaye Stacey(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Learning about functions involves much more than the transitions between process and object. The notation is complex, there are graphical and tabular representations to coordinate with the symbolic representation, and there are many special types of functions. Individual families of functions deserve special treatment and have special properties to learn about. However, developing the idea that a function is one object, not just a lot of calculations, is an important foundation for future mathematics that takes time to fully develop.3.9 Chapter SummaryAlgebra involves a new way of thinking that requires substantial change of perspective, alongside the considerable manipulative rule-based skills required to deal fluently and accurately with its notation. Students come to algebra after learning arithmetic, which of course provides essential skills for doing algebra. Perhaps surprisingly, however, the transition from arithmetic to algebra is not a smooth one. It is not just that the new algebra ideas are hard; it is also that many of the well-established ideas from arithmetic apply, but only when given an unfamiliar twist. Beginning students also bring to the learning of algebra their ideas about letters in other forms of writing. Algebra is a language particularly suited to explicitly describing mathematical relationships and structure. This too is a new orientation for students, who have previously dealt with structure only intuitively.As students learn algebra, they need to go through several cycles where mathematical processes are turned into mathematical objects. As they put on the new algebra spectacles, they begin to see algebraic entities that they could not see before. The first is that algebraic expressions need to be seen as objects, rather than as instructions for what to do with a number. Then equations have to change from a shorthand way of writing mathematical facts, to mathematical objects which themselves can be operated upon. Functions similarly are first encountered as rules for transforming numbers, but later become objects in their own right which have properties and can be transformed and combined to form other functions. Many entities in all branches of mathematics are created in this way. - Frank K. Lester(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Information Age Publishing(Publisher)

Addition, for example, is a computational method. It is also a func-tion with certain general properties. Likewise multi-plication by two is a table of number facts (1 × 2 = 2; 2 × 2 = 4; 3 × 2 = 6; 4 × 2 = 8) and also a function that maps a set of input values to unique output values. The latter idea can be expressed algebraically, for instance, through the mapping notation, x → 2x, the standard notation for functions, f(x) = 2x, or the graph on a Cartesian plane of a relation between x and y corre-sponding to the equation, y = 2x. It will help to bear these points in mind. It may first appear that the problems we gave children to solve are arithmetical. Upon looking more closely, the reader will note their algebraic character. The categories, arith-metical and algebraic , are not mutually exclusive. This does not mean that every idea, concept and technique from arithmetic is manifestly algebraic; however, each is potentially algebraic. Concepts such as equivalence can and should be treated early on in ways consistent with their usage in more advanced mathe-matics unless there are compelling reasons not to. EARLY ALGEBRA AND ALGEBRAIC REASONING ■ 699 That arithmetic is a part of algebra is neither obvious nor trivial, especially for those of us who fol-lowed the “arithmetic first, algebra much later” route through our own mathematics education. There is another reason that EA deserves special consideration. The mathematics curriculum tends to be a collection of isolated topics. Yet there are good arguments for treating mathematical (and scientific) concepts—particularly the more abstract concepts—as exceedingly relational. That is, much of their mean-ing derives from connections to other concepts. For example, one of the important meanings of “fraction” stems from the division of one integer by another. Yet division of integers is often treated in the curriculum without any reference to fractions (and vice-versa).- eBook - PDF

- Robert Reys, Mary Lindquist, Diana V. Lambdin, Nancy L. Smith(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

280 Problems, Patterns, and Relations 281 3. Algebra is an art, characterized by order and internal consistency. Children who are involved in algebraic thinking gain a better understanding of the underlying structure and properties of mathematics (Carpenter & Levi, 2000). 4. Algebra is a language that uses carefully defined terms and symbols. These terms and symbols enhance children’s ability to communicate about real-life situations and mathematics itself. 5. Algebra is a tool. In the past, many algebra courses presented algebra as a tool. But too often, students only learned the intricacies of the tool, without learning how to use it in any practical or meaningful way. The NCTM’s Principles and Standards (2000) do not recommend this limited approach to algebra, nor is it the approach we will present here. Algebra is a tool, but one that should be meaningful and useful. Bringing algebra to elementary school does not mean just adding one more topic to a crowded curriculum. It does mean using the mathematics in the curriculum to help chil- dren develop algebraic thinking or reasoning. As Carraher and Schliemann (2010, p. 27) write “The early mathemat- ics curriculum abounds with opportunities for promoting algebraic reasoning.” This chapter begins with a discussion of topics—problems, patterns, and relations—that will be used in the remainder of the chapter to build algebraic thinking. After discussing the algebraic language and symbols appropriate for ele- mentary students, we will look at ways to help children develop algebraic thinking through representing, generalizing, and justifying. Routine problems Routine problems are often considered exercises for practicing computation, but they can also be used to build algebraic understanding. You will find routine problems like these in every textbook: Routine Problem A: Before her birthday, Jane had 8 toy trucks. At her birthday party, she was given some more trucks. - eBook - ePub

- David Pimm(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6 MAKING REPRESENTATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS

There aren’t two things like abstraction and representation, each must contain the other.(David Hockney, 1993)Mathematics abounds with representations. In earlier chapters, I have described certain features of geometric, arithmetic and algebraic symbolism. This chapter concerns itself with both the processes of representing and the nature of representations themselves. In particular, it explores graphing and graphs as mediated by computers seen as dynamic imaging devices.The table below purports to set out a range of representational processes claimed to be of relevance to mathematics. Each process comes with a context for the acquisition of skills and ‘know-hows’, as well as opportunities for application in particular contexts. Janvier also offers the notion of ‘translation process’ from one form to(from Janvier, 1984, p. 29) another.The metaphor of translation is not neutral, however. The presumption behind translation is one of preservation of meaning—yet there seem to be many non-preservations in the varied list, with ‘modelling’ providing the clearest instance. A naive view of modelling, and indeed of representation, seems to suggest it is a one-to-one mapping (for example, from a situation described in an arithmetic ‘word problem’ to a ‘corresponding’ algebraic equation). Dienes’ multiple embodiments seem to suggest a many-to-one mapping, whereas my comments on Cabri-géomètre may suggest a many-to- many mapping. Dufour-Janvier et al. - eBook - PDF

- Anthony Orton, Leonard Frobisher(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6 Representation and symbolism INTRODUCTION Children experience mathematics in the form of representational systems. Repre-sentations have many appearances, ranging from oral words in children's natural language, through concrete representations such as multi-base blocks, to the most abstract of representations, written mathematical symbols. Some educators refer to any type of representation which takes the place of a mathematical idea as a symbol (Hiebert, 1988). Skemp (1971, p. 69) describes a symbol as 'a sound, or something visible, mentally connected to the idea. The idea is the meaning of the symbol.' In this chapter the term 'written symbol' is used for symbols such as '5', '+' and '=', to distinguish them from words, the symbols of a natural language. Increasingly, over recent years, many mathematics educators have expressed concern that an important obstacle to children's learning mathematics is an untimely and overhasty introduction of written symbolism at all stages of learn-ing, irrespective of the age and readiness of the children. As was emphasized in Chapter 5, the attaching of a name to a concept is fraught with difficulties. The further association of a symbol with a concept and its word referent provides impediments to learning mathematics. Mathematics, because of its unique written symbolism, is singularly susceptible to the detachment of symbols from the ideas which they represent. Throughout the whole of the mathematics curriculum, the names and symbols of concepts produce severe learning problems from which many children fail to recover. Dienes (1960) claims that learning diffi-culties with written symbols are due to the readiness of children to disengage a symbol from the concept it symbolizes, and then to proceed to manipulate the symbols, divorced from any concrete or pictorial representations. Unfortunately, teachers and textbooks encourage learners to pursue this pathway to confusion. - eBook - PDF

- Christer Bergsten, Bharath Sriraman(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Information Age Publishing(Publisher)

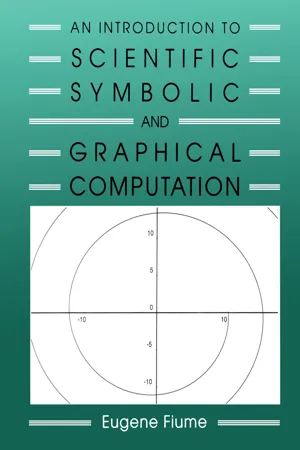

Beyond the Representation Given 29 by a rhetoric sequence (referring to a configuration), often along with a diagram (drawing), it now showed itself as an algebraic expression such as y = x 2 , still though, along with natural language. By defining the geo- metrical properties of a curve, it was possible by the use of coordinates to find an Algebraic Representation of this curve, 13 provided that the alge- braic manipulations could be coped with. As an example, from the defining property for a parabola as the loci for points with the same distance to a fixed point (focus) as to a fixed line (directrix), 14 an algebraic calculation can provide the equation x 2 = 4ay if the focus point is in (0, a) and the directrix is y = –a, using a current standard ON system. As the algebraic equation y = x 2 (or, with the use of set theory formalism, ( , ) : , 2 2 x y R y x x R { } ∈ = ∈ ) does not in itself constitute an icon of the curve it generates by its interpre- tation into coordinates for points in a standard coordinate system, its status as a representation of a parabola is abstract, as expressed by Fried (2007, pp. 216–217): To understand our own mathematical approach to objects such as the parab- ola, then, it is essential to see how Descartes relocates mathematical thought from the system of ideas of Apollonius’ world to a new system of ideas in which objects like the parabola are redefined and reinterpreted in terms of abstract relations (i.e., relations lifted up and away from special subject matter). By this “relocation” of mathematical thought into a new “system of ideas,” a historical metamorphosis of meaning took place. - Eugene Fiume(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- A K Peters/CRC Press(Publisher)

Chapter 1 The Representation of Functions In this chapter, we shall briefly review the familiar number systems with which we shall be working. We then discuss the common forms of functions defined over these number systems. Several representations for functions will be introduced, including explicit, implicit, parametric, and procedural forms. The parametric representation will be particularly useful to our work. We shall consider parametric functions in general, and then focus on an important subclass of parametric functions: the polynomials. The fast and accurate evaluation of functions is crucial to practical implementations. As examples of evaluation techniques, we derive several rendering algorithms for lines and circles. These examples will point out the some of the problems involved in converting mathematical representations to discrete representations such as visualisations on a display screen. Many other instances of these problems will arise in other chapters. Sections 1.1 to 1.3 are review material necessary for our discussion. Consult a calculus book for greater detail and generality. 1.1. Sets and Number Systems Mathematicians have developed a wide variety of number systems and operations over them. For our purposes, we are interested in just a few, although there are many others, such as the complex numbers and the quaternions, that are also extremely useful. The set of natural numbers , denoted N, is the set of non-negative whole numbers: 19 20 Chapter 1: The Representation of Functions The set of integers , Z, contains the signed whole numbers including zero: The set of rationals, Q, also include numbers with fractions: The set of real numbers , R, is a somewhat more difficult set of numbers to define. Each real number can be characterised in terms of a converging sequence of rational numbers. More specifically, any element x є R can be defined as the limit of a sequence of rational numbers jc 0, jc j , · · · that converges to x.- eBook - PDF

- Tom Bassarear, Meg Moss(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Section 6.3 Using Mathematical Models to Represent and Understand Quantitative Relationships 309 Mathematical models help us to represent and understand quantitative relationships. Models can help us describe situations as well as predict what may happen. Modeling begins in early elementary school when a student might use pictures or blocks to model that 1 5 3 5 8. Just as mathematical models is a category that NCTM uses for algebra, the Mathematical Practice 4 of the CCSS is titled, “Model with Mathematics.” Mathematical models are applied in and can help us understand real-life situations and make sense of them. Consider what a “model” is. We speak of model airplanes, and architects and engineers build a model of a building or a bridge before constructing the actual object. In one sense, a model is a representation of the original object. There are two important features of many models. First, the model contains many properties of the original object. Second, the model can be manipulated and studied to help us better understand the (usually larger and more complex) object. A mathematical model is a mathematical structure that approximates the features of a situation. A model, or representation, can take many forms: manipulative, diagram, graph, table, sketch, equation, words, and so on. Most problems and most mathematical concepts can be represented in different ways. Throughout this course thus far you have used several ways to model mathematical ideas and to solve problems. Students commonly ask which representation is “best,” but there is no “best way.” More useful questions are: Does this representation fit the purpose before us? Does it make sense in the context of the problem? Does it help us to solve the problem at hand? Let’s investigate a few examples. Math topics are very interrelated, so in many of these investigations you will see connections to ideas from previous sections in this chapter.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.