Mathematics

Integrating Trigonometric Functions

Integrating trigonometric functions involves finding the antiderivative of trigonometric expressions. This process often requires the use of trigonometric identities and substitution techniques to simplify the integral. Common trigonometric integrals include those involving sine, cosine, tangent, secant, and cosecant functions. These integrals are important in various fields such as physics, engineering, and mathematics.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Integrating Trigonometric Functions"

- eBook - PDF

- Mary Jane Sterling(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

2 Trigonometric Functions IN THIS PART . . . Define the basic trig functions using the lengths of the sides of a right triangle. Determine the relationships between the trig cofunctions and their shared sides. Extend your scope to angles greater than 90 degrees using the unit circle. Investigate the ins and outs of the domains and ranges of the six trig functions. Use reference angles to compute trig functions. Apply trig functions to real-world problems. CHAPTER 6 Describing Trig Functions 91 Chapter 6 Describing Trig Functions B y taking the lengths of the sides of right triangles or the chords of circles and creating ratios with those numbers and variables, our ancestors initi- ated the birth of trigonometric functions. These functions are of infinite value, because they allow you to use the stars to navigate and to build bridges that won’t fall. If you’re not into navigating a boat or engineering, then you can use the trig functions at home to plan that new addition. And they’re a staple for students going into calculus. You may be asking, “What is a function? What does it have to do with trigonom- etry?” In mathematics, a function is a mechanism that takes a value you input into it and churns out an answer, called the output. A function is connected to rules involving mathematical operations or processes. The six trig functions require one thing of you — inputting an angle measure — and then they output a number. These outputs are always real numbers, from infinitely small to infinitely large and everything in between. The results you get depend on which function you use. Although in earlier times, some of the function computations were rather tedious, today’s hand-held calculators, and even phones, make everything much easier. IN THIS CHAPTER » Understanding the three basic trig functions » Building on the basics: The reciprocal functions » Recognizing the angles that give the cleanest trig results » Determining the exact values of functions - No longer available |Learn more

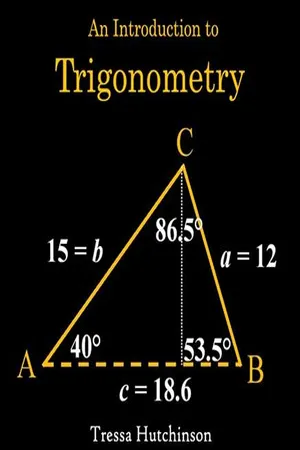

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 3 Trigonometric Functions In mathematics, the trigonometric functions (also called circular functions ) are func-tions of an angle. They are used to relate the angles of a triangle to the lengths of the sides of a triangle. Trigonometric functions are important in the study of triangles and modeling periodic phenomena, among many other applications. The most familiar trigonometric functions are the sine, cosine, and tangent. In the context of the standard unit circle with radius 1, where a triangle is formed by a ray originating at the origin and making some angle with the x -axis, the sine of the angle gives the length of the y -component (rise) of the triangle, the cosine gives the length of the x -component (run), and the tangent function gives the slope ( y -component divided by the x -component). More precise definitions are detailed below. Trigonometric functions are commonly defined as ratios of two sides of a right triangle containing the angle, and can equivalently be defined as the lengths of various line segments from a unit circle. More modern definitions express them as infinite series or as solutions of certain differential equations, allowing their extension to arbitrary positive and negative values and even to complex numbers. Trigonometric functions have a wide range of uses including computing unknown lengths and angles in triangles (often right triangles). In this use, trigonometric functions are used for instance in navigation, engineering, and physics. A common use in elementary physics is resolving a vector into Cartesian coordinates. The sine and cosine functions are also commonly used to model periodic function phenomena such as sound and light waves, the position and velocity of harmonic oscillators, sunlight intensity and day length, and average temperature variations through the year. - eBook - PDF

- Ron Larson(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

©iStockphoto/MirasWonderland 362 Chapter 5 Analytic Trigonometry 1.4 Functions GO DIGITAL 5.3 Solving Trigonometric Equations Use standard algebraic techniques to solve trigonometric equations. Solve trigonometric equations of quadratic type. Solve trigonometric equations involving multiple angles. Use inverse trigonometric functions to solve trigonometric equations. Introduction To solve a trigonometric equation, use standard algebraic techniques (when possible) such as collecting like terms, extracting square roots, and factoring. Your preliminary goal in solving a trigonometric equation is to isolate the trigonometric function on one side of the equation. For example, to solve the equation 2 sin x = 1, divide each side by 2 to obtain sin x = 1 2 . - eBook - PDF

- Ron Larson(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

©iStockphoto/MirasWonderland 522 Chapter 7 Analytic Trigonometry 1.4 Functions GO DIGITAL 7.3 Solving Trigonometric Equations Use standard algebraic techniques to solve trigonometric equations. Solve trigonometric equations of quadratic type. Solve trigonometric equations involving multiple angles. Use inverse trigonometric functions to solve trigonometric equations. Introduction To solve a trigonometric equation, use standard algebraic techniques (when possible) such as collecting like terms, extracting square roots, and factoring. Your preliminary goal in solving a trigonometric equation is to isolate the trigonometric function on one side of the equation. For example, to solve the equation 2 sin x = 1, divide each side by 2 to obtain sin x = 1 2 . - eBook - PDF

Precalculus

Functions and Graphs, Enhanced Edition

- Earl Swokowski, Jeffery Cole(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

362 CHAPTER 5 THE TRIGONOMETRIC FUNCTIONS Another method of solving is to note that the solutions are the open subintervals of that are not included in the intervals obtained in part (b). ■ The result discussed in the next example plays an important role in advanced mathematics. Sketching the graph of If , sketch the graph of f on , and investigate the behavior of as and as . SOLUTION Note that f is undefined at , because substitution yields the meaningless expression . We assign to . Because our screen has a 3 : 2 (horizontal : ver-tical) proportion, we use the viewing rectangle by since , obtaining a sketch similar to Figure 22. Using tracing and zoom features, we find it appears that There is a hole in the graph at the point ; however, most graphing utili-ties are not capable of showing this fact. Our graphical technique does not prove that as , but it does make it appear highly probable. A rigorous proof, based on the definition of sin x and geometric considerations, can be found in calculus texts. ■ An interesting result obtained from Example 7 is that if x is in radians and The last statement gives us an approximation formula for sin x if x is close to 0. To illustrate, using a calculator we find the following: We have now discussed two different approaches to the trigonometric functions. The development in terms of angles and ratios, introduced in Section 5.2, has many applications in the sciences and engineering. The defi-nition in terms of a unit circle, considered in this section, emphasizes the fact that the trigonometric functions have domains consisting of real numbers. Such functions are the building blocks for calculus. In addition, the unit circle approach is useful for discussing graphs and deriving trigonometric identities. You should work to become proficient in the use of both formulations of the trigonometric functions, since each will reinforce the other and thus facilitate your mastery of more advanced aspects of trigonometry. - eBook - PDF

- Ron Larson(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Introduction To solve a trigonometric equation, use standard algebraic techniques (when possible) such as collecting like terms, extracting square roots, and factoring. Your preliminary goal in solving a trigonometric equation is to isolate the trigonometric function on one side of the equation. For example, to solve the equation 2 sin x = 1, divide each side by 2 to obtain sin x = 1 2 . To solve for x, note in the graph of y = sin x below that the equation sin x = 1 2 has solutions x = π H208626 and x = 5π H208626 in the interval [0, 2π ). Moreover, because sin x has a period of 2π , there are infinitely many other solutions, which can be written as x = π 6 + 2nπ and x = 5π 6 + 2nπ General solution where n is an integer. Notice the solutions for n = ±1 in the graph of y = sin x. x x = - 2 x = - 2 x = x = π π π π π π 6 6 6 6 x = + 2 π π 6 1 - 1 y = 1 2 y = sin x π π - 5 x = + 2 π π 6 5 5 y The figure below illustrates another way to show that the equation sin x = 1 2 has infinitely many solutions. Any angles that are coterminal with π H208626 or 5π H208626 are also solutions of the equation. ( ) ( ) sin + 2 = n 5 5 6 6 6 1 2 π π π π sin + 2 = n 6 1 2 π π When solving trigonometric equations, write your answer(s) using exact values (when possible) rather than decimal approximations. Trigonometric equations have many applications in circular motion. For example, in Exercise 94 on page 235, you will solve a trigonometric equation to determine when a person riding a Ferris wheel will be at certain heights above the ground. iStockphoto.com/Flory Copyright 2018 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. - Stephen Garrett(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

2.3.5 Circular (trigonometric) functions You will be familiar with the basic trigonometric operations: sin, cos, and tan, from your school days. We begin with a brief summary of what one might recall from school trigonometry. Consider the right-angled triangle given in Figure 2.19(a). The angle θ can be related to the lengths of the opposite (O), adjacent (A), and hypotenuse (H) by the expressions sin θ = O H, cos θ = A H, tan θ = O A (2.20) Figure 2.19 Right-angled triangles. For example, a right-angled triangle with H = 5 and angle θ = 30° must be such that O = 5 sin (3 0 ∘) = 2.5 and A = 5 cos (3 0 ∘) ≈ 4.3301. Of course, the terms “opposite” and “adjacent” are defined with respect to a particular angle. If we instead work in terms of angle β = 90 − θ, the labels O and A are swapped over, as in Figure 2.19(b). The expressions in Eq. (2.20) therefore lead to the identities sin (θ) ≡ cos (9 0 ∘ − θ), cos (θ) ≡ sin (9 0 ∘ − θ), tan (θ) ≡ 1 tan (9 0 ∘ − θ) which of course assumes that tan (9 0 ∘ − θ) ≠ 0. In addition, expressions (2.20) are consistent with sin (θ) cos (θ) = tan (θ) sin 2 (θ) + cos 2 (θ) = 1 The second identity follows immediately from Pythagoras’ theorem, H 2 = O 2 + A 2. The identities given above are only a small number of the very many trigonometric identities that are listed in Appendix A. As you might imagine, our interest in trigonometric functions in this book is not motivated by triangles and simple geometry problems. Rather, trigonometric functions will prove very useful for their cyclical properties. The above descriptions hint at these properties. In particular, a circle consists of 360 degrees, denoted as 360°, and so any angle θ must, to all intents and purposes, be identical to the angle θ + 360 ° n, where n ∈ Z. Going further, it should then be the case that sin (θ) ≡ sin (θ + 36 0 ∘ n) cos (θ) ≡ cos (θ + 36 0 ∘ n) tan (θ) ≡ tan (θ + 36 0 ∘ n) (2.21) where n ∈ Z

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.