Physics

Center of Mass for a Rigid Body

The center of mass for a rigid body is the point where the mass of the body is concentrated. It is the average position of all the parts of the body, weighted according to their masses. The center of mass is an important concept in physics because it helps to simplify the analysis of the motion of a rigid body.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Center of Mass for a Rigid Body"

- eBook - PDF

- Philip Dyke, Roger Whitworth(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

When vector notation is introduced, the force F has a moment about O given by the vector product r F , where r is the position vector relative to O of any point on the line of action of the force (see Figure 10.2(b)). By conven-tion, the direction of the moment is perpendicular to the plane of r and F , similar to the definition of vector angular velocity (see section 6.10). 10.2 Centre of mass and centre of gravity The apparent motion relative to the geometrical centre of the rule in the above illustration suggests the importance of centre of mass in the rigid body model. Relative to the centre of mass all motion can be considered made up of (a) a translation and (b) a rotation. An Introduction to Rigid Body Dynamics 251 The centre of mass of a rigid body is a point fixed in the body at which a particle of the same mass can be placed so that all effects of translation are those satisfying Newton's laws for particle motion. The centre of gravity of a rigid body is the point at which the resultant weight of the body acts. For almost all purposes, the centre of mass and centre of gravity are the same point provided that the surrounding gravitational field remains constant for all of the body, and this is always the case except for some cosmological applications. In its simplest state, a rigid body is a collection of particles or small elements whose weights w p have the position vector r p relative to some fixed point O . The vector position of the centre of gravity r of this system is the point at which the resultant weight w p acts. - eBook - PDF

- Richard C. Hill, Kirstie Plantenberg(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- SDC Publications(Publisher)

The weight force (W) is applied at the center of gravity/mass of the body when drawing its free-body diagram. Since rigid bodies have size, a force applied to a body may generate a moment causing the body to rotate. Moments and center of gravity/mass are important concepts that must be understood when applying Newtonian mechanics to analyze the motion of a rigid body. We will devote some time reviewing centers of gravity/mass, mass moments of inertia, calculating moments and the rotational kinematic relationships. Conceptual Dynamics Kinetics: Chapter 6 – Rigid Body Newtonian Mechanics 6 - 4 6.2) CENTER OF MASS / GRAVITY The center of gravity of a body in many instances coincides with its mass center, but they do not share the same definition. The mass center is the mean location of all the mass in a given body or system. The center of gravity, usually denoted as G, is the mean location of the gravitational force acting on the body. This is the point where you apply the mg force in your free-body diagram. You can also think of the center of gravity as a balancing point. If you balance an object on your finger, you are balancing it at its center of gravity. The center of gravity and mass center are different concepts as illustrated by their definitions; however, in a uniform gravitational field they coincide. Therefore, they are often used interchangeably. Another concept that may get confused for the center of gravity is the centroid. The centroid of a body is the center of its volume. If the body has a uniform density, its centroid coincides with its center of mass. However, if the body is a composite or has varying density, its center of mass and its centroid may be in different locations. How do the concepts of center of mass and center of gravity differ? When do they coincide? Why do we need to know where the center of gravity of a body is located? How do the concepts of centroid (center of volume) and center of mass differ? When do they coincide? - eBook - PDF

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

225 C H A P T E R 9 Center of Mass and Linear Momentum 9.1 CENTER OF MASS Learning Objectives After reading this module, you should be able to . . . 9.1.1 Given the positions of several particles along an axis or a plane, determine the location of their center of mass. 9.1.2 Locate the center of mass of an extended, symmetric object by using the symmetry. 9.1.3 For a two-dimensional or three-dimensional extended object with a uniform distribution of mass, determine the center of mass by (a) mentally divid- ing the object into simple geometric figures, each of which can be replaced by a particle at its center and (b) finding the center of mass of those particles. Key Idea ● The center of mass of a system of n particles is defined to be the point whose coordinates are given by x com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i x i , y com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i y i , z com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i z i , or r → com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i r → i , where M is the total mass of the system. What Is Physics? Every mechanical engineer who is hired as a courtroom expert witness to recon- struct a traffic accident uses physics. Every dance trainer who coaches a ballerina on how to leap uses physics. Indeed, analyzing complicated motion of any sort requires simplification via an understanding of physics. In this chapter we discuss how the complicated motion of a system of objects, such as a car or a ballerina, can be simplified if we determine a special point of the system—the center of mass of that system. Here is a quick example. If you toss a ball into the air without much spin on the ball (Fig. 9.1.1a), its motion is simple—it follows a parabolic path, as we discussed in Chapter 4, and the ball can be treated as a particle. If, instead, you flip a baseball bat into the air (Fig. 9.1.1b), its motion is more complicated. Because every part of the bat moves differently, along paths of many different shapes, you cannot represent the bat as a particle. - eBook - PDF

The Mechanical Universe

Mechanics and Heat, Advanced Edition

- Steven C. Frautschi, Richard P. Olenick, Tom M. Apostol, David L. Goodstein(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

14.2 CENTER OF MASS OF A CONTINUOUS MASS DISTRIBUTION Before entering into the details of rigid-body rotation, we need to become more familiar with the techniques for locating the center of mass of an extended body. We recall from Chapter 11 that the center of mass of any extended body, rigid or not, plays a basic role in mechanics as the point f at which Newton's second law acts in the simple form Later in this chapter we shall find that complicated motion involving rotation is best analyzed if we divide the problem mentally into a motion of the center of mass and a rotation about the center of mass. We shall also find that in rotational problems a new quantity called moment of inertia enters quite naturally and plays the role of inertia. Calculation of moment of inertia is closely related to that for determining center of mass. Therefore we turn now to the center of mass of a continuous mass distribution, generalizing the discussion initiated in Chapter 11 . In Eq. (11.8) we defined the center of mass of a system of n positive masses m } , m 2 , . . ., m n located at discrete points r,, r 2 , . . ., r n by the weighted sum r = i, t »^ f , (11 8) where M = 2f =1 m, is the total mass of the system. When we deal with a system whose total mass is distributed along all the points of an interval or throughout some region in the plane rather than at a finite number of discrete points, the concepts of mass and center of mass are defined by integrals rather than sums. For example, consider a rod of length L made of material of varying density. Place the rod along the positive J: axis with one end at the origin, and let m(x) denote the mass of the portion of the rod from 0 to x. If there is a continuous function such that mfcc) -(x')dx Jo then •5 ax and the function is called the mass density of the rod. The number (x) is the mass per unit length at the point x. 14.2 CENTER OF MASS OF A CONTINUOUS MASS DISTRIBUTION 365 The integral 7. - David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

209 C H A P T E R 9 9.1 CENTER OF MASS KEY IDEA 1. The center of mass of a system of n particles is defined to be the point whose coordinates are given by x com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i x i , y com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i y i , z com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i z i , or r → com = 1 ___ M ∑ i=1 n m i r → i , where M is the total mass of the system. What Is Physics? Every mechanical engineer who is hired as a courtroom expert witness to recon- struct a traffic accident uses physics. Every dance trainer who coaches a ballerina on how to leap uses physics. Indeed, analyzing complicated motion of any sort requires simplification via an understanding of physics. In this chapter we discuss how the complicated motion of a system of objects, such as a car or a ballerina, can be simplified if we determine a special point of the system—the center of mass of that system. Here is a quick example. If you toss a ball into the air without much spin on the ball (Fig. 9.1.1a), its motion is simple—it follows a parabolic path, as we discussed in Chapter 4, and the ball can be treated as a particle. If, instead, you flip a baseball bat into the air (Fig. 9.1.1b), its motion is more complicated. Because every part of the bat moves differently, along paths of many different shapes, you cannot represent the bat as a particle. Instead, it is a system of particles each of which follows its own path through the air. However, the bat has one special point—the center of mass— that does move in a simple parabolic path. The other parts of the bat move around the center of mass. (To locate the center of mass, balance the bat on an outstretched finger; the point is above your finger, on the bat’s central axis.) You cannot make a career of flipping baseball bats into the air, but you can make a career of advising long-jumpers or dancers on how to leap properly into the air while either moving their arms and legs or rotating their torso.- David Halliday, Jearl Walker, Patrick Keleher, Paul Lasky, John Long, Judith Dawes, Julius Orwa, Ajay Mahato, Peter Huf, Warren Stannard, Amanda Edgar, Liam Lyons, Dipesh Bhattarai(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

CHAPTER 9 Centre of mass and linear momentum 9.1 The centre of mass LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading this module, you should be able to: 9.1.1 given the positions of several particles along an axis or a plane, determine the location of their centre of mass 9.1.2 locate the centre of mass of an extended, symmetric object by using the symmetry 9.1.3 for a two‐dimensional or three‐dimensional extended object with a uniform distribution of mass, determine the centre of mass by (a) mentally dividing the object into simple geometric fgures, each of which can be replaced by a particle at its centre, and (b) fnding the centre of mass of those particles. KEY IDEAS • The centre of mass of a system of n particles is defned to be the point whose coordinates are given by x com = 1 M Σ n i=1 m i x i , y com = 1 M Σ n i=1 m i y i , z com = 1 M Σ n i=1 m i z i , where M is the total mass of the system. In vector form, the centre of mass is given by r com = 1 M Σ n i=1 m i r i , • To fnd the centre of mass of a solid body, we integrate over the volume of the body: x com = 1 V ∫ xdV, y com = 1 V ∫ ydV, z com = 1 V ∫ zdV. Why study physics? Whether engaging in elite sports, climbing a set of stairs or strolling down the street, considerations of our centre of mass, kinetic energy and linear momentum determine our stability and capability to navigate our environment effectively and efficiently. Not all motion can be described as the motion of a single particle. For example, when an extended body rotates about either a stationary or moving axis, different points on the body have different velocities. Pdf_Folio:138 FIGURE 9.1 A snapshot of a rotating baton flying through the air. ZUMA Press Inc / Alamy Stock Photo An example is shown for two points in figure 9.1, which is a snapshot of a rotating baton flying through the air. The velocities of those two points at the instant of the snapshot are indicated and are obviously different in magnitude and direction.- eBook - PDF

Introduction to Physics

Mechanics, Hydrodynamics Thermodynamics

- P. Frauenfelder, P. Huber(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 4 D Y N A M I C S OF R I G I D B O D I E S 4 2 . MOTION OF THE CENTER OF MASS; THE CENTER OF MASS L A W A system of particles is any collection of particles between which there are forces of any nature. If these forces are such that the positions of all the particles in the system are fixed relative to each other, the system is called a rigid body. In this chapter, we shall be concerned only with those systems of particles making up a rigid body. We shall also discuss a few examples of groups of rigid bodies which themselves form nonrigid systems. In the following chapters we will consider other kinds of systems. The first important consideration in dealing with systems of particles is the distinction between internal and external forces. Internal forces always occur in pairs as an action and its reaction, and are therefore oppositely directed. The resultant of the internal forces for the entire system is zero. Since an action and its reaction have the same line of action, the resultant moment of the internal forces about any reference point is also zero. The internal forces of a system can therefore be ignored, and we can fix our attention on the external forces only. The external forces (that is, contact forces acting on the surface of a body, and forces which act at a distance, such as gravitation) have no reactions within the system, and can cause an acceleration of the masses making up the system. In addition, the external forces can have a resultant moment about an arbitrary reference point. The problem of the mechanics of systems can therefore be formulated through two questions. What is the acceleration produced by the external forces? What is the effect of the moment of the external forces? The first question is answered by the center of mass law. The second finds its solution in the angular momentum law. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Library Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 8 Rigid Body and Moment of Inertia Rigid Body The position of a rigid body is determined by the position of its center of mass and by its attitude (at least six parameters in total). In physics, a rigid body is an idealization of a solid body of finite size in which defor-mation is neglected. In other words, the distance between any two given points of a rigid body remains constant in time regardless of external forces exerted on it. Even though such an object cannot physically exist due to relativity, objects can normally be assumed to be perfectly rigid if they are not moving near the speed of light. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ In classical mechanics a rigid body is usually considered as a continuous mass distri-bution, while in quantum mechanics a rigid body is usually thought of as a collection of point masses. For instance, in quantum mechanics molecules (consisting of the point masses: electrons and nuclei) are often seen as rigid bodies. Kinematics Linear and angular position The position of a rigid body is the position of all the particles of which it is composed. To simplify the description of this position, we exploit the property that the body is rigid, namely that all its particles maintain the same distance relative to each other. If the body is rigid, it is sufficient to describe the position of at least three non-collinear particles. This makes it possible to reconstruct the position of all the other particles, provided that their time-invariant position relative to the three selected particles is known. However, typically a different and mathematically more convenient approach is used. The position of the whole body is represented by: 1. - eBook - PDF

- David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Your starting point would be to determine the person’s center of mass because of its simple motion. C H A P T E R 9 Center of Mass and Linear Momentum 9-1 CENTER OF MASS Learning Objectives After reading this module, you should be able to . . . Key Idea ● The center of mass of a system of n particles is defined to be the point whose coordinates are given by x com = 1 M ∑ n i =1 m i x i , y com = 1 M ∑ n i =1 m i y i , z com = 1 M ∑ n i =1 m i z i , or r → com = 1 M ∑ n i =1 m i r → i , where M is the total mass of the system. 9.01 Given the positions of several particles along an axis or a plane, determine the location of their center of mass. 9.02 Locate the center of mass of an extended, symmetric object by using the symmetry. 9.03 For a two-dimensional or three-dimensional extended object with a uniform distribution of mass, determine the center of mass by (a) mentally divid- ing the object into simple geometric figures, each of which can be replaced by a particle at its center and (b) finding the center of mass of those particles. 215 9-1 CENTER OF MASS The Center of Mass We define the center of mass (com) of a system of particles (such as a person) in order to predict the possible motion of the system. Here we discuss how to determine where the center of mass of a system of parti- cles is located. We start with a system of only a few particles, and then we consider a system of a great many particles (a solid body, such as a baseball bat). Later in the chapter, we discuss how the center of mass of a system moves when external forces act on the system. Systems of Particles Two Particles. Figure 9-2a shows two particles of masses m 1 and m 2 separated by distance d. We have arbitrarily chosen the origin of an x axis to coincide with the particle of mass m 1 . We define the position of the center of mass (com) of this two- particle system to be x com = m 2 m 1 + m 2 d. - eBook - PDF

- Stephen Lee(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Centre of mass Let man then contemplate the whole of nature in her full and grand mystery … It is an infinite sphere, the centre of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. Blaise Pascal 8 Q UESTION 8.1 Figure 8.1, which is drawn to scale, shows a mobile suspended from the point P. The horizontal rods and the strings are light but the geometrically shaped pieces are made of uniform heavy card. Does the mobile balance? If it does, what can you say about the position of its centre of mass? Figure 8.1 P Q UESTION 8.2 Where is the centre of mass of the gymnast in the picture (right)? 166 AN INTRODUCTION TO MATHEMATICS FOR ENGINEERS : MECHANICS You have met the concept of centre of mass in the context of two general models. ● The particle model The centre of mass is the single point at which the whole mass of the body may be taken to be situated. ● The rigid body model The centre of mass is the balance point of a body with size and shape. The following examples show how to calculate the position of the centre of mass of a body. An object consists of three point masses 8 kg, 5 kg and 4 kg attached to a rigid light rod as shown. Figure 8.2 Calculate the distance of the centre of mass of the object from end O. (Ignore the mass of the rod.) S OLUTION Suppose the centre of mass C is x m from O. If a pivot were at this position the rod would balance. Figure 8.3 For equilibrium R 8 g 5 g 4 g 17 g Taking moments of the forces about O gives: Total clockwise moment (8 g 0) (5 g 1.2) (4 g 1.8) 13.2 g Nm Total anticlockwise moment Rx 17 gx Nm. The overall moment must be zero for the rod to be in balance, so 17 gx 13.2 g 0 ⇒ 17 x 13.2 ⇒ x 1 1 3 7 .2 0.776. The centre of mass is 0.776 m from the end O of the rod. O C R 0.6 m x m 1.2 m 8 g 5 g 4 g Forces in N 8 kg O 5 kg 1.2 m 0.6 m 4 kg E XAMPLE 8.1 Note that although g was included in the calculation, it cancelled out. The answer depends only on the masses and their distances from the origin and not on the value of g . - eBook - ePub

Biomechanics of Dance

Applications of Classical Mechanics

- Melanie Lott(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

physical system subject to the laws of mechanics. In this chapter, the physical system of interest will be a dancer’s entire body. A crucial first step in any physical analysis is to create an idealized representation, or physical model, of the system. Given the extensive time to scratch the surface of the structure and function of the body in the previous chapter, one could become discouraged when contemplating an effective way to create a physical model of something as complex as the human body. So why not start with the simplest physical model we can think of – a single point particle? You may wonder if modeling a dancer as a point particle would be anywhere near realistic or provide any valuable insight at all. At its core, dancing arises from the relative motion of all the parts of the body, so it is true that we will have far from a complete picture if we only consider translational motion of a point particle located at the dancer’s center of mass (CM). However, as we will see, much valuable information can be uncovered from studying CM motion. Information such as what is or is not possible for the body to do based on the laws of physics, how the CM moves while different external forces act, or how a movement can be modified to decrease the magnitude of external force the dancer experiences and therefore reduce injury risk.This chapter begins by defining the center of mass and how to locate and track the CM position of a moving dancer. Describing how the CM moves (kinematics), and why the CM moves the way that it does (dynamics) when external forces act on a dancer is central to this chapter. By the end of chapter, we will interpret and explain experimental results of a dancer’s jumping data based on physical and biomechanical principles.3.1 Center of mass

The center of mass (CM) of a physical system is a weighted average position of where the system’s mass is located. For a system of two point particles with massesm 1andm 2at positionsandx →1(Fig. 3.1 ), the center of mass position isx →2. If=x →CMm 1+x →1m 2x →2m 1+m 2, the CM position is located at the midpoint betweenm 1=m 2m 1andm 2. If, the CM is closer tom 1>m 2m 1and vice versa. For N - Available until 25 Jan |Learn more

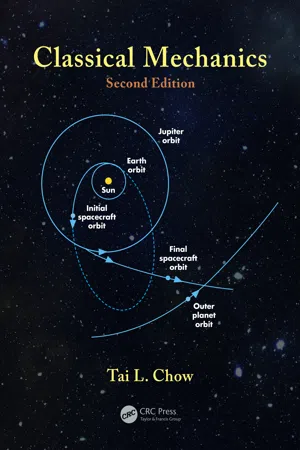

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

This is because a rigid body is set in motion instantaneously as a single unit when an external force is applied to it at any point. This means that signals (physical information) can be transmitted instantaneously from one point to another point in a rigid body, which violates the principles of special relativity. All macroscopic quantities that we introduced in Chapter 2 for systems of N interacting particles are also useful in this chapter: total mass center of mass (CM) M m R M m r i i N i i = = = ∑ 1 1 arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp i N i i P m r = ∑ ∑ = 1 total momentum total angular mom arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp dotnosp entum total torque arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp dotnosp arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp L m r r N r F i i i N i i e = × = × = ∑ 1 ( ) ) ( ) + ( ) = ∑ arrowrightnosp F i i N 1 For a rigid body with a continuous mass distribution, we can replace the summation by integra-tion over the volume of the body, for example, M m m i V i N = → ∫∫∫ ∑ = ρ d 1 12 378 Classical Mechanics © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC and arrowrightnosp arrowrightnosp R M r V V = ∫∫∫ 1 ρ d where d V is the element volume, and ρ is the density d m /d V . The form to be taken by d V and the limits of integration depend on the geometry of the body in consideration. The equations of motion and the general theorem established for systems of N particles in Chapter 3 can also be applied to rigid bodies. But certain simplifications are apparent because the possible types of motion are restricted. If one point of the body is fixed with respect to the primary inertial system, the only possible motion is that in which every other point moves on the surface of a sphere whose radius is the invariable distance from the moving point to the fixed point. If two points of the body are fixed, then the only possible motion is that in which all points except those on the line joining the two fixed points move in circles about centers located on the line.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.