Physics

Circuits

Circuits are pathways through which electric current flows, typically consisting of components such as wires, resistors, capacitors, and power sources. They can be either open or closed, allowing for the control and manipulation of electrical energy. Circuits are fundamental to the functioning of electronic devices and are a key concept in understanding the behavior of electricity.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Circuits"

- eBook - PDF

- Michael Tammaro(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

An electric circuit is a conducting path along which charges flow, driven by differences in electric potential. The late 1800s saw the first widespread use of electric Circuits with the advent of electric lighting. Since then, electric Circuits have had an integral role in almost every technological development. The miniaturization of electric Circuits and devices has led to tremendous breakthroughs in computers and communications. This photograph shows part of a silicon computer chip, which itself is a complex electrical circuit. The gold wires connect the chip to pins that allow it to be plugged into a circuit board. (The image here is a scanning electron micrograph at 90× magnification.) Eye of Science/Science Source/Photo Researchers** Direct Current Circuits 20 538 Electric Current and Electromotive Force | 539 20.1 Solve problems dealing with the basic definition of electric current. The movement of electric charges from place to place plays a fundamental role in almost every technology and convenience of modern life. The basic quantity that defines the movement of charges through conductors is called electric current, or simply current. A closed path of conducting material along which current flows is called an electric circuit. Here in Chapter 20 we explore electric Circuits, restricting ourselves to direct current (DC) Circuits—that is, those in which the current at a particular point is always in the same direction. Electric Current There are a wide variety of materials that conduct electricity. The charge carriers in liquid solutions or gases may be positive or negative ions. Electrons are the charge carriers in metals. The movement of electrons through a metal is pictured schematically in Animated Figure 20.1.1. In this two-dimensional view, the large circles represent the metal atoms, which are arranged in a regular array, called a lattice. - eBook - PDF

Physics of Electronic Materials

Principles and Applications

- Jørgen Rammer(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

5 Electric Circuit Theory Electronics is about pushing electrons around inside matter in a controlled manner, creating flows of electric charge in Circuits. This should be done to provide calculated voltages over components, thereby providing the right current flows, ensuring the right voltage drops over other components, etc. Designing the functioning of electronic Circuits can be done without understanding the physics of the components. All that is needed is knowledge of the components’ current–voltage relationships, their I – V characteristics: what is the cur-rent response through a component to an electric potential difference, or voltage, between its terminals, or vice versa, what is the needed current through a device to provide a certain voltage across its terminals. The art and craft of electronics then emerges from understand-ing electronic circuitry as represented by symbolic circuit diagrams. The main intention of this book is to provide the physical understanding of the I – V characteristics of electronic components, the physics of electronics, but electric Circuits are discussed throughout the chapters, here basic circuit theory. 5.1 Wires and Currents An electric circuit consists of electronic components connected by wires , thin filaments of good conducting material such as a clean metal. The resistance of a wire is assumed so small in comparison with the resistance of other components that the wires can be assumed perfect conductors, i.e. having zero resistivity or infinite conductivity. Inside a perfect con-ductor, the electric field vanishes, since the slightest field would create an infinite current, i.e. instantaneously nullifying it. The electric potential is thus the same in a wire, and no charge inhomogeneity exists in wires. In a wire an electric current thus flows without the presence of a voltage difference; the charged electrons flow like an incompressible liquid. - eBook - PDF

Circuit Analysis with PSpice

A Simplified Approach

- Nassir H. Sabah(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Part I Basic Concepts in Circuit Analysis 3 Objective and Overview This chapter introduces some basic notions on electric Circuits before embarking on circuit analysis in the fol- lowing chapters. The chapter begins by explaining what electric Circuits are, what they are used for, and what conservation laws they obey. The primary circuit variables of current and voltage are defined with reference to a useful and easy- to-follow, hydraulic analogy. The significance of direc- tion of current and polarity of voltage is emphasized because of the key roles these play in circuit analysis. The relation of current and voltage to power and energy is derived, and active and passive circuit elements are characterized by the way they handle energy. The three passive circuit parameters of resistance, capacitance, and inductance are justified as accounting for three basic attributes of the electromagnetic field, namely, energy dissipation and energy storage in the electric and magnetic fields. The chapter concludes with an exami- nation of the idealizations and approximations made in the Circuits approach. 1.1 What Are Electric Circuits and What Are They Used For? Definition: An electric circuit is an interconnection of com- ponents that affect electric charges in some characteristic manner. An example is a battery connected to a heater through a switch, as illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1.1. Figure 1.2 is the corresponding circuit dia- gram in terms of symbols for the three components. When the switch is in the closed position, as shown, it allows electric charges to flow through the heater. In doing so, the charges impart some of their energy to the heater, thereby generating heat and raising the temperature of the heater metal. The battery restores energy to the electric charges, thereby allowing them to flow continuously through the circuit. Opening the switch interrupts the flow of charges and turns off the heater. - Russell Smith(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

3.1 BASIC CONCEPTS OF ELECTRIC Circuits An electric circuit is the complete path of an electric current, along with any necessary elements, such as a power source and a load. When the cir-cuit is complete so that the current can flow, it is termed closed or made ( Figure 3.1 ). When the path of current flow is interrupted, the circuit is termed open , or broken ( Figure 3.2 ). The opening and closing of electri-cal switches connected in series with electrical loads control the operation of loads in the circuit. Section 3.1 Basic Concepts of Electric Circuits 41 Copyright 2019 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. All electric Circuits must have a complete path for electrons to flow through, a source of electrons, and some electric device (load) that requires electric energy for its operation. Figure 3.3 shows a complete circuit with the basic components labeled. Electric Circuits supply power and control loads through the use of switches. An alternating current power supply is the most common source of the electric energy used in the electric Circuits of a heating, cooling, or refrigeration system. A direct current power supply, such as the dry cell battery, is often the source of electron flow in electric meters. Other than for meters, though, direct current is rarely used as a source of elec-tric energy. Two special applications of direct current used today are electronic air cleaners and solid-state modules used for some types of special control, such as a defrost control, fur-nace controls, ignition modules, and overcurrent protection.- eBook - PDF

- Stephen Herman(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 124 SECTION 2 Basic Electric Circuits OBJECTIVES After studying this unit, you should be able to ● discuss the properties of series Circuits. ● list three rules for solving electrical values of series Circuits. ● calculate values of voltage, current, resistance, and power for series Circuits. ● calculate the values of voltage drop in a series circuit using the voltage divider formula. Preview E lectric Circuits can be divided into three major types: series, parallel, and combination. Combination Circuits are Circuits that contain both series and parallel paths. The first type discussed is the series circuit. 6–1 Series Circuits A series circuit is a circuit that has only one path for current flow (Figure 6–1) . Because there is only one path for current flow, the current is the same at any point in the circuit. Imagine that an electron leaves the negative terminal of the battery. This electron must flow through each resistor before it can complete the circuit to the positive battery terminal. One of the best examples of a series-connected device is a fuse or circuit breaker (Figure 6–2) . Because fuses and circuit breakers are connected in series with the rest of the circuit, all the circuit current must flow through them. If the current becomes excessive, the fuse or circuit breaker will open and disconnect the rest of the circuit from the power source. 6–2 Voltage Drops in a Series Circuit Voltage is the force that pushes the electrons through a resistance. - eBook - PDF

Linear Circuit Theory

Matrices in Computer Applications

- Jiri Vlach(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Apple Academic Press(Publisher)

1 B ASIC C ONCEPTS 1 INTRODUCTION This chapter starts with the concept of electric current and voltage, introduces basic termi-nology and shows how networks are drawn. It gives a brief overview of all linear elements which are used in the network theory, plus a few of the most important practical devices. After this informal explanation we give definitions of the independent current and voltage sources, of resistors, of power delivered or consumed. Three fundamental laws are stated: the Ohm’s law and the Kirchhoff’s current and voltage laws. Based on this knowledge we study the voltage and current dividers and also explain how to obtain equivalent resistances for combinations of resistors. 1.1. VOLTAGES AND CURRENTS Network theory deals with voltages, currents, network elements and signals; in this sec-tion we will consider in detail the first two, and also introduce some basic concepts and typical signals. Electric current is a flow of electrons and is measured in amperes , denoted by the let-ter A . Voltage is a force which causes electrons to flow and is measured in volts , denoted by V . The concept of current is usually somewhat easier to grasp because we can visualize it as a current of water. When we talk about the flow of water, we associate it with a certain direction and we know, from daily experience, that the direction is from a higher point to a lower point. We also accept without difficulties that there must be some force which determines the direc-tion of the flow. A similar situation exists in electrical networks and the force that pushes the current through the elements is the voltage. The word potential can be used as well. In the early days of electricity, only chemical batteries were available and the con-cept of electrons was unknown. One of the connecting points of the battery was arbitrarily marked with a + sign, the other with a − sign and it was assumed that the current flowed into the external network from the + terminal to the − terminal. - S. B. Lal Seksena, Kaustuv Dasgupta(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2.1 Introduction The seventeenth century was the century for theorization of electricity. The electrical technology became more and more advanced and complex. Direct current technology was dominating the new inventions. It was very necessary to mathematize the different parameters of these complex electrical connections and Circuits. We had to develop a new mathematical model to calculate and determine the voltage, current power etc. of a circuit at different branches and nodes without measuring it directly. Some important theorems regarding electrical circuit were mutated during the last half of the century. These theorems work good with some constrain in the nature of the circuit. Before the semiconductor Circuits or electronic Circuits came into the picture these theorems were successfully used to determined different parameters of an electrical circuit. In this chapter let us find out and discuss about some of those electrical circuit theories. 2.2 Basic Concepts: Electric Circuit, Loop, Mesh etc. a. Electric circuit: An electric circuit or electric network is a combination of different electric components (discussed in the next topic) via loop and branches of conductors. b. Node: A node is a junction of an electric circuit where two or more circuit components are connected together. c. Branch: Branch is the part of the circuit which lies between two junctions or nodes in an electric circuit. d. Loop: Loop is the closed path in an electric circuit in which no element or node is connected more than once. e. Mesh: Mesh is such a loop that does not involve no other loop in it. So every mesh is a loop but all loops are not meshes. 2 ELECTRICAL Circuits Prerequisite Knowledge Fundamental of Current Electricity Basic understanding of Electric Circuit Electrical Circuits 35 Let us understand the circuit and its nodes, branches, loops and meshes with a simple example of Wheatstone bridge circuit In Fig.- Frank R. Spellman, Nancy E. Whiting(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

258 Handbook of Mathematics and Statistics for the Environment part of the load. For simplicity, however, we usually think of the connecting wiring as having no resistance, as it would be tedious to assign a very low resistance value to the wires every time we wanted to solve a problem. Control devices might be switches, variable resistors, circuit breakers, fuses, or relays. A complete pathway for current flow, or closed circuit (Figure 11.17), is an unbroken path for current from the emf, through a load, and back to the source. A circuit is open (see Figure 11.18) if a break in the circuit (e.g., open switch) does not provide a complete path for current. Key Point: Current flows from the negative (–) terminal of the battery, shown in Figures 11.17 and 11.18, through the load to the positive (+) battery terminal and then continues through the battery from the positive (+) terminal to the negative (–) terminal. As long as this pathway is unbroken, it is a closed circuit and current will flow; however, if the path is broken at any point, it becomes an open circuit and no current flows. To protect a circuit, a fuse is placed directly in the circuit (see Figure 11.19). A fuse will open the circuit whenever a dangerously large current begins to flow (i.e., when a short circuit condition occurs caused by an accidental connection between two points in a circuit offering very little resis-tance). A fuse will permit currents smaller than the fuse value to flow but will melt and therefore break or open the circuit if a larger current flows. 11.7.2.1 Schematic Representation The simple Circuits shown in Figures 11.17, 11.18, and 11.19 are displayed in schematic form. A schematic diagram (usually shortened to “schematic”) is a simplified drawing that represents the electrical, not the physical, situation in a circuit. The symbols used in schematic diagrams are the electrician’s shorthand; they make the diagrams easier to draw and easier to understand.- Frank R. Spellman(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

A dangerously large current will flow when a short circuit occurs. A short circuit is usually caused by an accidental connection between two points in a circuit that offers very little resistance and passes an abnormal amount of current. A short circuit often occurs because of improper wiring or broken insulation. 10.17 PARALLEL DC Circuits The principles we applied to solving simple series circuit cal-culations for determining the reactions of such quantities as voltage, current, and resistance can be used in parallel and series–parallel Circuits. 10.17.1 P ARALLEL C IRCUIT C HARACTERISTICS A parallel circuit is defined as one having two or more components connected across the same voltage source (see Figure 10.44). Recall that a series circuit has only one path for current flow. As additional loads (resistors, etc.) are added to the circuit, the total resistance increases and the total current decreases. This is not the case in a parallel circuit. In a parallel circuit, each load (or branch) is con-nected directly across the voltage source. In Figure 10.44, commencing at the voltage source ( E b ) and tracing coun-terclockwise around the circuit, two complete and separate paths can be identified in which current can flow. One path is traced from the source through resistance R 1 and back to the source, the other from the source through resistance R 2 and back to the source. 10.17.2 V OLTAGE IN P ARALLEL C IRCUITS Recall that in a series circuit the source voltage divides pro-portionately across each resistor in the circuit. In a parallel circuit (see Figure 10.44), the same voltage is present across all of the resistors of a parallel group. This voltage is equal E 1 = 20 volts R 1 E 2 = 60 volts C + 60 volts B + 20 volts A 0 volts 80 volts R 2 FIGURE 10.41 Use of ground symbols. E b R 2 + – R 1 I Conducting chassis I FIGURE 10.42 Ground used as a conductor. R 1 R 2 E b Switch Fuse (open) + – FIGURE 10.43 Open circuit with blown fuse.- eBook - PDF

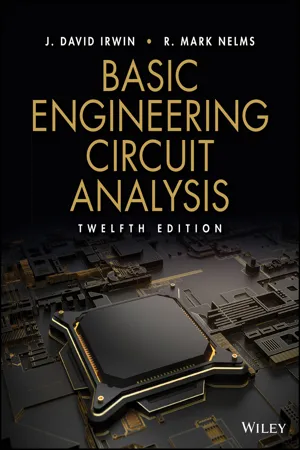

- J. David Irwin, R. Mark Nelms(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

In addition to these two types of currents, which have a wide variety of uses, we can generate many other types of currents. We will examine some of these other types later in the book. In the meantime, it is interesting to note that the magnitude of cur- rents in elements familiar to us ranges from soup to nuts, as shown in Fig. 1.4. I 1 = 2 A I 2 = −3 A (a) (b) Circuit 1 Circuit 2 FIGURE 1.2 Conventional current flow: (a) positive current flow; (b) negative current flow. i(t) t t i(t) (a) (b) FIGURE 1.3 Two common types of current: (a) alternating current (ac); (b) direct current (dc). 1.2 Basic Quantities 3 We have indicated that charges in motion yield an energy transfer. Now we define the voltage (also called the electromotive force, or potential) between two points in a circuit as the difference in energy level of a unit charge located at each of the two points. Voltage is very similar to a gravitational force. Think about a bowling ball being dropped from a ladder into a tank of water. As soon as the ball is released, the force of gravity pulls it toward the bottom of the tank. The potential energy of the bowling ball decreases as it approaches the bottom. The gravitational force is pushing the bowling ball through the water. Think of the bowling ball as a charge and the voltage as the force pushing the charge through a circuit. Charges in motion represent a current, so the motion of the bowling ball could be thought of as a current. The water in the tank will resist the motion of the bowling ball. The motion of charges in an electric circuit will be impeded or resisted as well. We will introduce the concept of resistance in Chapter 2 to describe this effect. Work or energy, w(t) or W , is measured in joules (J); 1 joule is 1 newton meter (N . m). Hence, voltage [υ (t) or V] is measured in volts (V), and 1 volt is 1 joule per coulomb; that is, 1 volt = 1 joule per coulomb = 1 newton meter per coulomb.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.