Physics

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton was a renowned physicist who made significant contributions to the field of physics. He is best known for his laws of motion and universal gravitation, which laid the foundation for classical mechanics. Newton's work revolutionized our understanding of the physical world and remains fundamental to the study of physics today.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Isaac Newton"

- eBook - PDF

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.(Publisher)

induction. Here the idea of science as a collaborative under-taking, conducted in an impersonally methodical fashion and animated by the intention to give material benefits to human-kind, is set out with literary force. Isaac Newton and the Rise of Modern Science It was Isaac Newton who was finally to discover the way to a new synthesis in which truth was revealed and God was preserved. Newton was both an experimental and a mathe-matical genius, a combination that enabled him to establish both the Copernican system and a new mechanics. His method was simplicity itself: ``from the phenomena of motions to investigate the forces of nature, and then from these forces to demonstrate the other phenomena''. Newton's genius guided him in the selection of phenomena to be investigated, and his creation of a fundamental mathematical tool ± the calculus (simultaneously invented by Leibniz) ± permitted him to submit the forces he inferred to calculation. The result was the Principia , which appeared in 1687. Here was a new physics that applied equally well to terrestrial and celestial bodies. Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo were all justified by Newton's analysis of forces. Descartes was utterly routed. Newton's three laws of motion and his principle of universal gravitation sufficed to regulate the new cosmos, but only, Newton believed, with the help of God. Gravity, he more than once hinted, was direct divine action, as were all forces for order and vitality. Absolute space, for Newton, was essential, because space was the ``sensorium of God'', and the divine abode must necessarily be the ultimate coordinate system. Finally, Newton's analysis of the mutual perturbations of the planets caused by their individual gravitational fields THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION 45 predicted the natural collapse of the solar system unless God acted to set things right again. The first work which would make Newton's reputation was Book I of the Opticks . - eBook - PDF

- Delo E. Mook, Thomas Vargish(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

2 THE CLASSICAL BACKGROUND Then ye how now on heavenly nectar fare, Come celebrate with me in song the name Of Newton, to the Muses dear; for he Unlocked the hidden treasuries of Truth: So richly through his mind had Phoebus cast The Radiance of his own divinity. Nearer the gods no mortal may approach. —The ode dedicated to Newton by Edmund Halley in The Principia 2.1 NEWTONIAN PHYSICS If Einstein's theory of relativity seems strange to us, it is largely because we remain Newtonians in our conception of the physical world. To discuss relativity theory and its impact on our established world view, we must therefore first consider Newton's contribution to our intellectual heritage, especially Newtonian mechanics or ' 'classical'' mechanics, as it is called. 1 Newton set forth his model of mechanics in his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (usually referred to as the Principia). The pub-lication of this book in 1687 was one of the most significant events in the history of Western culture. 2 Alexander Pope reflected the deep feelings of Newton's heirs in his famous couplet: 1 The adjective classical is now applied to all physics that preceded the developments of quantum theory and relativity theory. Modern students still begin their training in physical science by learning classical physics; quantum theory and relativity theory are taught as de-velopments from the established classical (or Newtonian) world view. 2 The standard translation of the Principia is Florian Cajori, Sir Isaac Newton's Mathe-matical Principles of Natural Philosophy and His System of the World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966). All references to the Principia will be to this edition. Newton prepared 3 editions of the book, the last in 1726. 2.2 SPACE, TIME, AND MOTION 25 Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night: God said, Let Newton bel and all was light. 3 In the Principia Newton established what was to be the foundation of mod-ern physical science. - eBook - PDF

Planetary Motions

A Historical Perspective

- Norriss S. Hetherington(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

17 Isaac Newton AND GRAVITY In ancient Greek and medieval European cosmology, solid crystalline spheres provided a physical structure for the universe and carried the planets in their motions around the Earth. Then Copernicus moved the Earth out of the center of the universe, Tycho Brahe shattered the crystalline spheres with his obser- vations of the comet of 1577, and Kepler replaced circular orbits with ellipses. How, now, could the planets continue to retrace their same paths around the Sun for thousands of years? The answer, encompassing both physical cause and mathematical description, came forth from Isaac Newton. Newton’s remarkable intellectual accomplishments include creation of the calculus, invention of the reflecting telescope, development of the corpuscular theory of light (its colored rays separated by a prism), and development of the principles of gravity and terrestrial and celestial motion. Newtonian think- ing came to permeate not only the physical world but also intellectual fields, including politics and economics, where others were encouraged to seek uni- versal natural laws of the sort Newton had found in physics and astronomy. Nor was eighteenth-century literature oblivious to the Newtonian revolution in thought. He changed history, perhaps more so than any other single person. Newton’s father, although a wealthy farmer and lord of his own manor, could not sign his name. Probably he would not have educated his son; his brother did not. Newton was born in 1642, the year Galileo died, three months after his father’s death, premature, and so small that he was not expected to survive. When he was three, his mother remarried, and Newton was left in his grand- mother’s care. Difficult early years probably contributed to his difficult mature personality. He rejoined his mother seven years later, after his stepfather died, leaving his mother wealthy. Her family was educated, and she soon sent Newton off to school. - eBook - PDF

Practical Matter

Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687–1851

- Margaret C. Jacob, Larry Stewart(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

C H A P T E R 1 The Newtonian Revolution Born in 1642 in Lincolnshire in England, in the year Galileo died, Isaac Newton grew up in the midst of civil wars. He was a country boy whose father died before he was born and whose mother ap-pears to have had little time for him once she remarried. At Cam-bridge University, he waited on student tables to pay his way. This boy with an unsettled passage became a philosopher and mathema-tician who revolutionized our understanding of the heavens. Yet probably his first love throughout his long, celebrated life—he died, world famous, in 1727—was theology. This man of the Bible, who believed that God would end the world and usher in a millennial paradise, all to be preceded by the conversion of the Jews, ironically did more than any other mortal to make the world seem like an or-dered, rational, certain place, bounded by mathematically know-able laws that would stay in place forever. The private Newton whose fantasies about the end of the world endlessly fascinate us today stayed largely hidden in his own life-time, known only to a select few of his very small circle of friends. 1 We know that he wrote his most famous book, Mathematical Prin-ciples of Natural Philosophy (1687, hereafter, his Principia ), to make humankind believe more deeply in the deity. But that purpose does not leap out when the reader first approaches the text. How readers prior to the mid-nineteenth century read the Principia, what 9 they could take from it, synthesize, or rework, how its legacy en-twined with other ideas and institutions—that process vitally con-cerns us in this and subsequent chapters. At the foundation of Newton’s science—and all subsequent Western science—rested one bedrock assumption. Put in Newton’s own words, “nature is exceedingly simple and conformable to her-self” and that means whatever “holds for greater motions, should hold for lesser ones as well.” 2 The rules, Newton said in the Prin-cipia, were universal. - eBook - ePub

Revival: A History of Modern Culture: Volume II (1934)

The Enlightenment 1687 - 1776

- Preserved Smith(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter IINewtonian Science1. Astronomy from the Death of Galileo to the Publication of Newton’s “Principia”

In the year that Galileo died (1642) there was born another astronomer and physicist destined to win even greater renown. The fame of Sir Isaac Newton is, indeed, as supreme and all but matchless in the realm of science as is that of Shakespeare in poetry and that of Napoleon in arms. The posthumous son of a small yeoman, he was born at Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, and grounded in the elements of religion and letters by his stepfather, a clergyman. Attending the King’s School at Grantham, he mastered Latin so well as to become head boy, and to induce his family to send him to Cambridge University. While his four years at Trinity College (1661-65) gave him a mastery of mathematics and of polite learning and a considerable interest in ancient history and in theology, his real education—as is almost always the case with genius—was won by himself in extra-curricular studies. An acquaintance with an apothecary gave him an introduction to chemistry, and the reading of Kepler’s Optics opened his mind to the wonders of physics. The acquisition of this book was the crucial date in his development. From the German scientist, whose influence over him can hardly be exaggerated, he obtained the starting-point for his investigations in all the three fields—astronomy, physics, and mathematics—to which he contributed so much.With the characteristic precocity of genius he made his most important discoveries before he had reached the age of twenty-four. The law of gravitation, the principles of the calculus, and the theory of light, all germinated in his mind as early as the year 1666. Except his precocity, however, nothing is more remarkable than his slowness in publication. Unwilling to put forth anything premature or incomplete, he spent years of arduous toil in testing and perfecting his ideas before he submitted them to the judgment of the public. - Available until 25 Jan |Learn more

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

25 © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Newtonian Mechanics The foundation of Newtonian mechanics is the three laws of motion that were postulated by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) as a result of the combination of experimental evidence and a great deal of intuition. 2.1 THE FIRST LAW OF MOTION (LAW OF INERTIA) Newton’s first law of motion describes the behavior of a body that has no net outside force acting on it. This law may be stated as follows: A body remains in a state of rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless it is compelled to change that state by an applied force. This contradicts the view of motion held by Aristotle, the Greek philosopher who lived in 340 B.C. He said that the natural state of an object was to be at rest and that it moved only if driven by a force. Was Aristotle right? We all observe that moving objects tend to slow down and come to rest. But this is because of friction. If friction is negligible, a body in motion will remain in motion. Galileo Galilee (1564–1642) first observed this. Rather than rely solely on intuition and general observation as Aristotle did, Galileo tested his ideas with carefully designed experiments and started the mod-ern chain of development in the study of motion. Galileo used two smooth inclined planes set end-to-end, one tilted down and the other up, and released balls of different weights, from rest, down the first inclined plane. (It is similar to that of balls falling vertically, but it is easier to observe because the speeds are slower.) When a ball was released and moved down the first inclined plane, it swept past the bottom and ascended the second inclined plane to about the same height (a little less—fric-tion cannot be eliminated completely) regardless of the tilt of the second plane. He also observed that when the angle of the incline of the second plane was made less steep, the ball slid farther in the horizontal direction (Figure 2.1). - eBook - PDF

Theoretical Concepts in Physics

An Alternative View of Theoretical Reasoning in Physics

- Malcolm S. Longair(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

7, Plate 1 of issue 81, 1672. The two crowns show the improvement in magnification of Newton’s telescope (Fig. 2) over the refracting telescope (Fig. 3), such as that used by Galileo. These were great experimental achievements, but Newton had a pathological dislike of writing up his work for publication. The systematic presentation of his optical work was only published in 1704 as his Opticks, long after his discoveries and inventions were made. 4.4.2 The Law of Gravity Newton’s most famous achievement of his years at Woolsthorpe was the discovery of the law of gravity. The calculations carried out in 1665–66 were only the beginning of the story, but they contained the essence of the theory which was to appear in its full glory in his Principia Mathematica of 1687. As Newton himself recounted, he was aware of Kepler’s third law of planetary motion, which was deeply buried in Kepler’s Harmony of 53 4.4 Lincolnshire 1665–67 Fig. 4.3 A vector diagram illustrating the origin of centripetal acceleration. the World. This volume was in Trinity College library and it is likely that Isaac Barrow, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, drew Newton’s attention to it. In Newton’s own words: the notion of gravitation [came to my mind] as I sat in contemplative mood [and] was occasioned by the fall of an apple. 8 Newton asked whether or not the force of gravity, which makes the apple fall to the ground, is the same force which holds the Moon in its orbit about the Earth and the planets in their orbits about the Sun. To answer this question, he needed to know how the force of gravity varies with distance. He derived this relation from Kepler’s third law by a simple argument. First, he needed an expression for centripetal acceleration, which he rederived for himself. Nowadays, this formula can be derived by a simple geometrical argument using vectors. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

Newton's laws of motion Newton's First and Second laws, in Latin, from the original 1687 edition of the Principia Mathematica. Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that form the basis for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between the forces acting on a body and its motion due to those forces. They have been expressed in several different ways over nearly three centuries, and can be summarized as follows: ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ 1. First law : Every body remains in a state of rest or uniform motion (constant velocity) unless it is acted upon by an external unbalanced force. This means that in the absence of a non-zero net force, the center of mass of a body either remains at rest, or moves at a constant speed in a straight line. 2. Second law : A body of mass m subject to a force F undergoes an acceleration a that has the same direction as the force and a magnitude that is directly proportional to the force and inversely proportional to the mass, i.e., F = m a . Alternatively, the total force applied on a body is equal to the time derivative of linear momentum of the body. 3. Third law : The mutual forces of action and reaction between two bodies are equal, opposite and collinear. This means that whenever a first body exerts a force F on a se cond body, the second body exerts a force − F on the first body. F and − F are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. This law is sometimes referred to as the action-reaction law , with F called the action and − F the reaction. The action and the reaction are simultaneous. The three laws of motion were first compiled by Sir Isaac Newton in his work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica , first published on July 5, 1687. Newton used them to explain and investigate the motion of many physical objects and systems. - eBook - PDF

Superstrings and Other Things

A Guide to Physics, Second Edition

- Carlos Calle(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

These counterweights not only stopped the incline from increasing for nine months, but actually straightened it by about 2.5 cm. In 1995, the lead bricks were replaced by a second ring anchored with steel cables to one of the deep clay layers. In 2008, after over ten years of work, engineers declared that the tower should remain stable for at least 200 years. 42 Superstrings and Other Things: A Guide to Physics, Second Edition exhaustion, as he told his biographer. During that same period, Newton developed the main ideas of what he called his theory of fluxions , which we know today as calculus. It was also during that glorious period of creativity that Newton laid the foundations of his celestial mechanics with his discovery of the law of gravity. “All this was in the two plague years of 1665 & 1666,” Newton wrote, “for in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention, & minded Mathematics & Philosophy [i.e. physics] more than at any time since.” It is not clear why Newton, after having conceived the idea of universal gravitation, did not attempt to publish anything about it for almost 20 years. When he finally did, at the instigation of one of his closest friends, the scientist Edmond Halley, he published what many consider the greatest scientific treatise ever written, the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica . The physics of the Principia still guides our communication satellites, our space shuttles, and the spacecraft that we send to study the solar system (Figure 3.5). The Principia is divided into three books or parts. In Book One, The Motion of Bodies, Newton develops the physics of moving bodies. This first part is preceded by “axioms, or laws of motion:” Law I : Every body continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it. - eBook - PDF

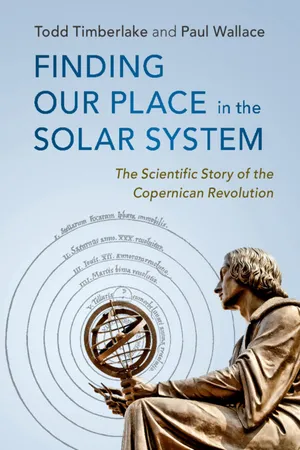

Finding our Place in the Solar System

The Scientific Story of the Copernican Revolution

- Todd Timberlake, Paul Wallace(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

As we will see, the inertia of an object plays an important role in determining how the object will move, so Newton treated it as a force. Newton’s other two forces were “impressed force” and “centripetal force.” Impressed force is anything that acts on a body to change the body’s motion. Centripetal force is a particular type of impressed force that acts always to push the body toward a particular fixed point. Note that the definition of centripetal force implies that a force has a direction as well as a magnitude, which means that forces are also vectors just like velocity or quantity of motion. 48 i Experiments with pendulums had shown that gravity was weaker in some locations on Earth than in others. ii Newton’s definitions did not make it clear that quantity of motion, and other vector quantities, had a direction as well as a magnitude. However, the vector nature of these quantities was clear from the way Newton used them in the Principia. 262 The system of the world After presenting these and other definitions, Newton included a scholium (or explanatory note). He attempted to provide philosophical definitions of absolute time and space. He distinguished between absolute motion (the change of an object’s location within absolute space) and relative motion (the change of an object’s location relative to other objects). He claimed that the only way to tell the difference between absolute and relative motion was to consider the forces that produce the motions. The absolute motion of a body could only be changed by impressed forces acting on that body, while the relative motion of a body could be changed without any forces acting on the body. Philosophically, Newton’s claims about absolute time and space are hard to justify and they don’t seem to play an important role in the rest of the Principia. Note, however, that the relative motions are the same in both the Copernican and Tychonic theories. - eBook - PDF

Half-Hours with Great Scientists

The Story of Physics

- Charles G. Fraser(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Toronto Press(Publisher)

Edmund Halley not only assisted me with his pains in correcting the press [proof-reading] and taking care of the schemes [diagrams], but it was to his solicitations that its becoming public is owing. LAWS OF MOTION One of the best known passages of the Principia is Newton's statement of the laws of motion, which he enunciated as axioms or fundamental assumptions. His wording of the first law runs as follows: Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum nisi quatenus illud a viribus impresses cogitur statum suum mutare, which is generally translated thus: Every body continues in its state of rest or of uniform motion in a straight line unless compelled by external force to change that state. We have seen the same idea expressed by Aristotle, Galileo, and Huygens, and the phrase external force sounds like an echo of Galileo. But for two centuries now, Newton's statement or a translation of it has been accepted as standard, although the wording uniform motion in a straight line contains a redundancy which is not in the original. Newton, of course, was always ready to give full credit to his predecessors and contemporaries, as when he said, If I have been able to see a little farther than some others, it was because I stood on the shoulders of giants. The School of Newton 133 We all see countless illustrations of the first law of motion every day and apply it—when we shovel snow or coal, stamp snow from our shoes, ride a bicycle, throw a ball and so on. The law says that the velocity of every body is constant unless changed by force. It says that acceleration is produced by force only. Thus it assumes the existence of force and defines it as the only agent that can produce acceleration. It also implies for every body, as did Aristotle's statement, the property of offering resisting force in opposition to any body that changes or tends to change its velocity. This property, as we have seen, Kepler called inertia. - Ivor Grattan-Guinness(Author)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

In the first place he had to avoid symbolic algebra: he did so by referring directly to geometric figures and their properties. Secondly he had to avoid infinitesimals: instead of making recourse to infinitesimals, he deployed limit procedures. We will find in section 4 many examples of these geometric limit procedures in the Principia. Many reasons lay behind Newton’s shift for the geometry of the ancients and his critical attitude towards the moderns, an attitude which is somewhat in resonance with his anti- cartesianism in philosophy, and with his belief in a prisca philosophia (the wisdom of the ancients) which he fully endorsed most probably in the 1690s. Here we note that he was often to underline the fact that the objects of the synthetic geometric method of fluxions have an existence in Nature. The objects of geometric inquiry are generated by motions which one observes in the study of the natural world (one can think of the ellipses traced by planets). 2 EARLY STUDIES ON THE MOTION OF BODIES AND ON PLANETARY MOTION 2.1 Initial influences Newton’s earliest studies on the laws of motions occurred during the Winter of 1664 [Herivel, 1965; Nauenberg, 1994]. As in the case of mathematics, his starting point was Descartes. He commented upon Book 2 of Descartes’s Principia philosophiae (1644) with particular penetration. It is believed that the title of Newton’s magnum opus was conceived of as a criticism to the French philosopher, whose work would have lacked adequate math- ematical principles. From Descartes Newton learned about the law of inertia: what was to become the first law of motion of the Principia. A body moves in a straight line with constant speed until a force is applied to it. Unaccelerated rectilinear motion is a status in which a body naturally perseveres: it does not need, as it was thought in the Aristotelian tradition, a mover.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.