Mathematics

Newton's First Law

Newton's First Law, also known as the law of inertia, states that an object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in motion will remain in motion with a constant velocity unless acted upon by an external force. This law provides the foundation for understanding the behavior of objects in the absence of external influences.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Newton's First Law"

- eBook - PDF

Superstrings and Other Things

A Guide to Physics, Second Edition

- Carlos Calle(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Newton’s first law is also called the law of inertia. We have spoken of forces pushing and pulling on objects to change their states of motion. These forces caused the objects to move. However, we all know that we can push on a heavy piece of furniture, like a dresser for example, and fail to move it. In this case the force applied is balanced by the frictional force between the dresser and the floor. We would say that the net force acting on the dresser is zero. Forces are vector quantities and this knowledge helps us understand why we can have several forces applied to an object and still have a net or resultant force equal to zero. When the two teams participating in a tug-of-war contest are unable to drag each other across the center line (Figure 3.7), the net force on the rope is zero, even though the individual team members, each of different strengths, pull with different forces. The sum of all the individual forces pulling on the rope is zero and the rope does not move. In Figure 3.7, we have the three different forces F 1 , F 2 , and F 3 exerted by each one of the three women acting on the left side of the rope, and the three additional forces, F ′ 1 , F ′ 2 , and F ′ 3 , exerted by the men, all different, and differing from the first ones, acting on the right side of the rope. In this vector diagram, the lengths of the vector forces are proportional to their mag-nitudes. Since the total length of the vectors on the left is equal to the total length of the three vectors acting on the right, the vector sum of these six forces is equal to zero. Thus the net force acting on the rope is zero and we say that the rope is in equilibrium. Newton’s first law says that, if the net force acting on an object is zero, the object will not change its state of motion. Thus, if the object is in equilibrium, its velocity remains constant. A constant velocity means that the velocity can take up any value that does not change, including zero, the case of an object at rest. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

Newton's laws of motion Newton's First and Second laws, in Latin, from the original 1687 edition of the Principia Mathematica. Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that form the basis for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between the forces acting on a body and its motion due to those forces. They have been expressed in several different ways over nearly three centuries, and can be summarized as follows: ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ 1. First law : Every body remains in a state of rest or uniform motion (constant velocity) unless it is acted upon by an external unbalanced force. This means that in the absence of a non-zero net force, the center of mass of a body either remains at rest, or moves at a constant speed in a straight line. 2. Second law : A body of mass m subject to a force F undergoes an acceleration a that has the same direction as the force and a magnitude that is directly proportional to the force and inversely proportional to the mass, i.e., F = m a . Alternatively, the total force applied on a body is equal to the time derivative of linear momentum of the body. 3. Third law : The mutual forces of action and reaction between two bodies are equal, opposite and collinear. This means that whenever a first body exerts a force F on a se cond body, the second body exerts a force − F on the first body. F and − F are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. This law is sometimes referred to as the action-reaction law , with F called the action and − F the reaction. The action and the reaction are simultaneous. The three laws of motion were first compiled by Sir Isaac Newton in his work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica , first published on July 5, 1687. Newton used them to explain and investigate the motion of many physical objects and systems. - eBook - ePub

Doing Physics with Scientific Notebook

A Problem Solving Approach

- Joseph Gallant(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Chapter 5Newton’s Laws of Motion

In the previous chapters on kinematics, we described motion in a quantitative sense. Once we know an object’s acceleration, we can describe its motion in terms of position, velocity, and time. Knowing how its motion changes lets us calculate how far, how fast, and how long the object moves.Now we move to a branch of physics known as dynamics. Dynamics is the study of the effects of forces on an object’s motion. Dynamics explains changes in motion by relating the cause of the changes (forces) to the effect (acceleration). Newton’s Second Law provides the rule relating the acceleration to the net force.There are three ingredients to Newton’s Second Law: the object’s acceleration, mass, and the net force acting on it. As we discussed in Chapter 2, the object’s acceleration is the rate of change in its velocity. Mass is a property of the object that determines how much change the net force produces. An object’s mass tells you how difficult it is to change its velocity and how much matter it has.A force is a push or a pull that can cause changes in motion. Forces are vectors, so they have magnitude and direction. This is consistent with your experience. When you exert a force on something, two things matter: how hard you push or pull and which way. Often objects have more than one force acting on them. The net force acting on an object is the vector sum of all the forces acting on it.Newton’s First Law

Newton’s First Law tells us what happens when there is no net force acting on an object.Newton’s 1st Law: An object will remain in a state of rest or continue in motion at a constant velocity unless compelled to change by a non-zero net force.When there is no net force acting on the object, there is no change in the object’s velocity. If it is at rest, it remains at rest. If it is moving, it keeps moving at constant velocity. Since velocity is a vector, constant velocity means no change in both speed and direction. Motion at constant velocity is motion in a straight line at a constant speed. - eBook - PDF

Applied Mathematics

Made Simple

- Patrick Murphy(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

(2) The First Law The first law provides the definition of force which we have already quoted in Chapter One: 'force is that which tends to change the state of rest or uniform motion of a body'. It should be noted that it is the resultant force on the body which is being discussed in each case. Consider for example a body resting on a table. Since the body is in contact with the table, the weight W x of the body is being balanced by an equal and opposite reaction force of the table on the body. The resultant force is R _ w x = 0. If we apply the force of our weight W 2 by standing on the body, and if 68 Applied Mathematics Made Simple the table is able to withstand the increased force, then R — (W x 4-W 2 ) = 0. That is, the magnitude of the action force has increased from W x to W x -f-W 2i but so has the magnitude of the reaction. So the resultant force on the body remains zero and the body continues in its state of rest—unless, of course, the table collapses as in Fig. 56 (b in which case the resultant force on the body is only its weight W x . We therefore agree that a body will remain at rest unless an external force is used to set it in motion. (Q) (b) Fig. 56 However, the idea that a body would continue to move with uniform velocity in a straight line if left to itself without any applied forces is not so easy to accept: we have no personal experience of bodies which manage to do this. Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence to lead us to consider that the truth of this law is a most reasonable assumption. Here on earth the main difficulty in putting the first law to the test is that when a body moves there is always a resistance to its motion, either by the atmosphere or the surface of contact or both. When a body slides across a surface there is always a force of friction which opposes the continuation of the motion. We attempt to minimize this frictional force by moving the body across what are called 'smoother' surfaces, i.e. - eBook - PDF

- John D. Cutnell, Kenneth W. Johnson, David Young, Shane Stadler(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Friction The force that an object encounters when it moves or attempts to move along a surface. It is always directed parallel to the surface in question. Tension The tendency of a rope (or similar object) to be pulled apart due to the forces that are applied at either end. Equilibrium The state an object is in if it has zero acceleration. Mathematically, equilibrium means = 0. Apparent Weight The force that an object exerts on the platform of a scale. It may be larger or smaller than the true weight, depending on the acceleration of the object and the scale. Chapter 4 39 Newton's laws of Motion First Law An object continues in a state of rest or in a state of motion at a constant speed along a straight line, unless compelled to change that state by a net force. By "net" force we mean the vector sum of all of the forces acting on an object. For example, consider a spaceship in deep space, isolated from any other object or force. If the ship is stationary, it will remain so. But if the ship is moving (its rocket engines are shut down) it will continue to move in a straight line with a constant speed. So if the ship were traveling into deep space at say, 100 000 milh, it would continue to move at this speed in a straight line, even without the rocket engines firing, until an outside force acted to stop or change its motion. Second Law When a net force 2:F acts on an object of mass m, the acceleration a that results is directly proportional to the net force and has a magnitude that is inversely proportional to the mass. The direction of the acceleration is the same as the direction of the net force. This statement is usually written as LF=ma or a=LF/m (4.1) The symbol 2:F represents the net force, that is, the vector sum of all the forces acting on an object. This means that the components of the forces must be examined. For example, in two dimensions, equation (4.1) becomes Equations (4.1) and (4.2) can be used to determine the units of force. - eBook - PDF

- Daniel Kleppner, Robert Kolenkow(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

The law is often stated in words such as “A uniformly moving body continues to move uniformly unless acted on by a force,” but the underlying concept is re-ally the idea of an isolated body. Because all interactions decrease with distance, we can take “isolated” to mean a body that has been removed so far from other bodies that interactions are negligible. A coordinate system can always be found in which the body moves uniformly. From this point of view we can state Newton’s first law as follows: Newton’s first law of motion is the assertion that inertial systems exist. Newton’s first law is part definition and part experimental fact. Iso-lated bodies move uniformly in inertial systems by virtue of the defini-tion of an inertial system. In contrast, the assertion that inertial systems exist is a statement about the physical world. Newton’s first law raises a number of questions such as what we really mean by an “isolated body,” but we defer these for the present. 2.5 Newton’s Second Law We now turn to how the rider on the air track behaves when it is no longer isolated. Suppose that we pull the rider with a rubber band. When we start to stretch the rubber band, the rider starts to move. If we move our hand ahead of the rider so that the rubber band’s stretch is constant, we 52 NEWTON’S LAWS find that the rider moves in a wonderfully simple way; its speed increases uniformly with time. The rider moves with constant acceleration . Now suppose that we repeat the experiment but with a di ff erent rider, perhaps one a good deal bigger than the first. If the same rubber band is stretched to the same length as before, it causes a constant accelera-tion, but the acceleration di ff ers from the previous case. Apparently the acceleration depends not only on what we do to the object, since pre-sumably we do the same thing in each case, but also on some property of the object. - eBook - PDF

Systemic Yoyos

Some Impacts of the Second Dimension

- Yi Lin(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Auerbach Publications(Publisher)

More specifically, after introducing the new figurative analysis method, we will have a chance to generalize all three laws of motion so that external forces are no longer required for these laws to work. As what is known, these laws are one of the reasons why physics is an exact science. It can be expected that these generalized forms of the laws will be equally applicable to social sciences and humanity areas as their classic forms in natural science. To this end, please consult the remaining chapters in this book. The presentations in this chapter and the following two chapters are based on Lin (2007). 4.1 The Second Stir and Newton’s First Law of Motion Newton’s first law says that an object will continue in its state of motion unless compelled to change by a force impressed upon it. This property of objects, their natural resistance to changes in their state of motion, is called inertia. Based on the theory of blown-ups, one has to address two questions not settled by Newton in his first law: Question 4.1. If a force truly impresses on the object, the force must be from outside of the object. Then, where can such a force be from? Question 4.2. This problem is about the so-called natural resistance of objects to changes in their state of motion. Specifically, how can such a resistance be considered natural? Newton’s Laws of Motion n 53 It is because uneven densities of materials create twisting forces that fields of spinning currents are naturally formed. This end provides an answer and explana-tion to Question 4.1. Based on the yoyo model (Figure 1.1), the said external force comes from the spin field of the yoyo structure of another object, which is a level higher than the object of our concern. The forces from this new spin field push the object of concern away from its original spin field into a new spin field. If there were not such a forced traveling, the said object would continue its original movement in its original spin field. - eBook - PDF

- Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

Newton’s second law of motion is more than a definition; it is a relationship among acceleration, force, and mass. It can help us make predictions. Each of those physical quantities can be defined independently, so the second law tells us something basic and universal about nature. The next section introduces the third and final law of motion. 4.4 Newton’s Third Law of Motion: Symmetry in Forces There is a passage in the musical Man of la Mancha that relates to Newton’s third law of motion. Sancho, in describing a fight with his wife to Don Quixote, says, “Of course I hit her back, Your Grace, but she’s a lot harder than me and you know what they say, ‘Whether the stone hits the pitcher or the pitcher hits the stone, it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.’” This is exactly what happens whenever one body exerts a force on another—the first also experiences a force (equal in magnitude and opposite in direction). Numerous common experiences, such as stubbing a toe or throwing a ball, confirm this. It is precisely stated in Newton’s third law of motion. Newton’s Third Law of Motion Whenever one body exerts a force on a second body, the first body experiences a force that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force that it exerts. This law represents a certain symmetry in nature: Forces always occur in pairs, and one body cannot exert a force on another without experiencing a force itself. We sometimes refer to this law loosely as “action-reaction,” where the force exerted is the action and the force experienced as a consequence is the reaction. Newton’s third law has practical uses in analyzing the origin of forces and understanding which forces are external to a system. We can readily see Newton’s third law at work by taking a look at how people move about. Consider a swimmer pushing off from the side of a pool, as illustrated in Figure 4.9. She pushes against the pool wall with her feet and accelerates in the direction opposite to that of her push. - eBook - PDF

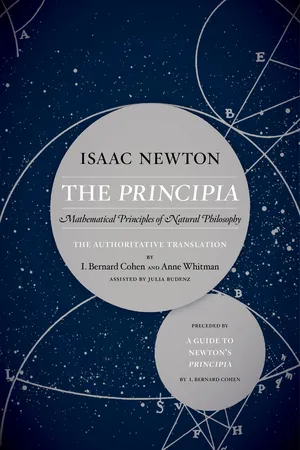

The Principia: The Authoritative Translation and Guide

Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

- Sir Isaac Newton(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

For Descartes, as has been 1. W. J. 'sGravesande, Mathematical Elements of Physic%s, prov'd by Experiments, being an Introduction to Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophy, revised and corrected by John Keill (London: printed for G. Strahan . . ., 1720), vol. 1, book 1, pt. 1, chap. 16. 2. Jane Ruby, The Origins of Scientific 'Law,' Journal of the History of Ideas 47 (1986): 341-360. 109 no G U I D E : C H A P T E R 5 mentioned, the statement of the principle of inertia requires two laws rather than one, a feature which indicates that Descartes's laws of nature are not formulated in a way that would enable him to infer forces from motions, as Newton does in his Principia. Often the question has been raised why there are both a first and a second law since, as Rouse Ball put it, the first law seems to be a consequence of the second law, so that it is not clear why it was enunciated as a separate law. 3 That is, if the second law is that F = mA or F = = , then it dv dtt dt follows that if F = 0, A = = 0. The only trouble with this line of thought dt mdV is that F = mA = is the second law for a continually acting force F, dt whereas Newton's second law (as stated in the Principia) is expressed in terms of an impulsive force. For such a force, the force is proportional to the change in momentum and not the rate of change in momentum. Thus a possible clue to Newton's thinking is found in the examples used in the discussion of the first law, analyzed below, each one of which is (unlike the forces in law 2) a continually acting force. Accordingly, we may conclude that law 1 is not a special case of law 2 since law 1 is concerned with a different kind of force. A more interesting question to be raised, however, is why Newton believed he needed a first law since the principle of inertia had already been anticipated in def. 3 and also in def. 4. It would seem that Newton's First Law was not so much intended as a simple restatement of the principle previously embodied in def. - eBook - PDF

- William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff Sanny(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

The object experiences acceleration due to gravity. • Some upward resistance force from the air acts on all falling objects on Earth, so they can never truly be in free fall. Chapter 5 | Newton's Laws of Motion 253 • Careful distinctions must be made between free fall and weightlessness using the definition of weight as force due to gravity acting on an object of a certain mass. 5.5 Newton’s Third Law • Newton’s third law of motion represents a basic symmetry in nature, with an experienced force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to an exerted force. • Two equal and opposite forces do not cancel because they act on different systems. • Action-reaction pairs include a swimmer pushing off a wall, helicopters creating lift by pushing air down, and an octopus propelling itself forward by ejecting water from its body. Rockets, airplanes, and cars are pushed forward by a thrust reaction force. • Choosing a system is an important analytical step in understanding the physics of a problem and solving it. 5.6 Common Forces • When an object rests on a surface, the surface applies a force to the object that supports the weight of the object. This supporting force acts perpendicular to and away from the surface. It is called a normal force. • When an object rests on a nonaccelerating horizontal surface, the magnitude of the normal force is equal to the weight of the object. • When an object rests on an inclined plane that makes an angle θ with the horizontal surface, the weight of the object can be resolved into components that act perpendicular and parallel to the surface of the plane. • The pulling force that acts along a stretched flexible connector, such as a rope or cable, is called tension. When a rope supports the weight of an object at rest, the tension in the rope is equal to the weight of the object. If the object is accelerating, tension is greater than weight, and if it is decelerating, tension is less than weight. - eBook - PDF

- John D. Cutnell, Kenneth W. Johnson, David Young, Shane Stadler(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

If the masses of the rope and each pulley are negligible and if the pulleys are friction-free, the tension is transmitted a y P T T T T +x +y (a) (b) Free-body diagram of the unit T T W = mg W = mg B B B B B B Figure 4.34 (a) A window washer pulls down on the rope to hoist the scaffold up the side of a building. The force T B results from the effort of the window washer and acts on him and the scaffold in three places, as discussed in Example 18. (b) The free-body diagram of the unit comprising the man and the scaffold. CONCEPT SUMMARY 4.1 The Concepts of Force and Mass A force is a push or a pull and is a vector quantity. Con- tact forces arise from the physical contact between two objects. Noncontact forces are also called action-at-a-distance forces, because they arise without physical contact between two objects. Mass is a property of matter that determines how difficult it is to accelerate or decelerate an object. Mass is a scalar quantity. 4.2 Newton’s First Law of Motion Newton’s first law of motion, sometimes called the law of inertia, states that an object continues in a state of rest or in a state of motion at a constant velocity unless compelled to change that state by a net force. Inertia is the natural tendency of an object to remain at rest or in motion at a constant velocity. The mass of a body is a quantitative measure of inertia and is measured in an SI unit called the kilogram (kg). An inertial reference frame is one in which Newton’s law of inertia is valid. 4.3 Newton’s Second Law of Motion/4.4 The Vector Nature of Newton’s Second Law of Motion Newton’s second law of motion states that when a net force SF B acts on an object of mass m, the accel- eration a B of the object can be obtained from Equation 4.1. This is a vector equation and, for motion in two dimensions, is equivalent to Equations 4.2a and 4.2b. In these equations the x and y subscripts refer to the scalar components of the force and acceleration vectors.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.