Physics

Inertia

Inertia is the tendency of an object to resist changes in its state of motion. It is a fundamental property of matter and is related to an object's mass. Objects at rest tend to stay at rest, and objects in motion tend to stay in motion, unless acted upon by an external force.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Inertia"

- eBook - PDF

- Patrick Hamill(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

If necessary, we can take the origin of coordinates to be at the center of the Sun, or even the center of the galaxy. Some people think of the first law as a definition of an Inertial reference frame and what it is really telling us is that the next two laws are only valid in such a reference frame. The physical property called “Inertia” is associated with the fact that a moving body tends to preserve its state of motion. The expression, “preserving its state of motion” means the body has constant velocity. A locomotive has more Inertia than a ping-pong ball. The word Inertia thus appears to be a synonym for mass. Because it requires a great force to change the motion of an 52 3 NEWTON’S LAWS: DETERMINING THE MOTION object with great mass, one often hears the expression, “Mass is a measure of the Inertia of a body.” But the tendency of a body to maintain its state of motion also depends on its velocity. It is easier to deflect a slowly moving five gram ping-pong ball than a speeding five gram bullet. In this case, Inertia appears to be a synonym for momentum. It is very difficult to define fundamental quantities such as mass, distance, time, charge, and so on. Similarly, Inertia is usually described by the somewhat vague expression that it is the tendency of a body to maintain its state of motion. (We do not have a formula for Inertia!) On the other hand, the law of Inertia (Newton’s First Law) is perfectly well defined. 3.3 Newton’s Second Law and the Equation of Motion Newton’s second law can be stated in the form: The rate of change of the momentum of an isolated body is equal to the net external force applied to it. In equation form this is written: d p dt = F, (3.1) where F is the net or total force acting on the body. (You may prefer to write it as F net or as F.) Now momentum is defined as p = mv, so F = d dt (mv) = dm dt v + m d v dt . If the mass is constant, Newton’s second law takes on the familiar form F = ma. - eBook - PDF

- Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

Experiments have thoroughly verified that any change in velocity (speed or direction) must be caused by an external force. The idea of generally applicable or universal laws is important not only here—it is a basic feature of all laws of physics. Identifying these laws is like recognizing patterns in nature from which further patterns can be discovered. The genius of Galileo, who first developed the idea for the first law, and Newton, who clarified it, was to ask the fundamental question, “What is the cause?” Thinking in terms of cause and effect is a worldview fundamentally different from the typical ancient Greek approach when questions such as “Why does a tiger have stripes?” would have been answered in Aristotelian fashion, “That is the nature of the beast.” True perhaps, but not a useful insight. Mass The property of a body to remain at rest or to remain in motion with constant velocity is called Inertia. Newton’s first law is often called the law of Inertia. As we know from experience, some objects have more Inertia than others. It is obviously more difficult to change the motion of a large boulder than that of a basketball, for example. The Inertia of an object is measured by its mass. Roughly speaking, mass is a measure of the amount of “stuff” (or matter) in something. The quantity or amount of matter in an object is determined by the numbers of atoms and molecules of various types it contains. Unlike weight, mass does not vary with location. The mass of an object is the same on Earth, in orbit, or on the surface of the Moon. In practice, it is very difficult to count and identify all of the atoms and molecules in an object, so masses are not often determined in this manner. Operationally, the masses of objects are determined by comparison with the standard kilogram. Check Your Understanding Which has more mass: a kilogram of cotton balls or a kilogram of gold? Solution They are equal. - eBook - PDF

Mechanics

Lectures on Theoretical Physics

- Arnold Sommerfeld(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER I MECHANICS OF A PARTICLE § 1. Newton's Axioms The laws of motion will be introduced in axiomatic form; they summarize in precise form the whole body of experience. First law : Every material body remains in its state of rest or of uniform rectilinear motion unless compelled by forces acting on it to change its state. 1 We shall at first withhold explanation of the concept of force introduced in this law. We notice that the states of rest and of uniform (rectilinear) motion are treated on equal footing and are regarded as natural states of the body. The law postulates a tendency of the body to remain in such a natural state; this tendency is called the Inertia of the body. One often speaks of Galileo's law of Inertia instead of Newton's first law in referring to the above axiom. We must say in this connection that while it is perfectly true that Galileo arrived at this law long before Newton (as a limiting result of his experiments with sliding bodies on planes of vanishing inclination), we find it characteristic of Newton that the law holds top position in his system. Newton's word body will, for the time being, be replaced by the words particle or mass point. To formulate the first law mathematically we shall make use of definitions 1 and 2 preceding it in the Principia. Definition 2 : The quantity of motion is the measure of the same, arising from the velocity and the quantity of matter conjunctly. 2 The quantity of motion is hence the product of two factors, the velocity, whose meaning is geometrically evident, 8 and the quantity of 1 We mention here, and in connection with what is to follow, the book Die Mechanik in ihrer Entwickelung (8th ed., F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1923; translated into English under the title The Science of Mechanics, Open Court Publishing Co., LaSalle, 111., 1942) by Ernst Mach. - eBook - PDF

Finding our Place in the Solar System

The Scientific Story of the Copernican Revolution

- Todd Timberlake, Paul Wallace(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Newton noted that mass was proportional to weight, but he was careful not to identify it with weight, because he knew that the weight of an object could change from place to place. i In fact, Newton’s definition of mass, or quantity of matter, is not entirely clear since we now think of density as mass divided by volume, which would make Newton’s definition circular. However, in Newton’s day the relative densities of several substances were reasonably well known, so it was not inappropriate for him to make use of that concept. What Newton was searching for here was a property of an object that could not be increased or decreased (without adding or removing matter). As we will see, Newton used mass as a measure of an object’s resistance to changes in motion. Newton then defined an object’s “quantity of motion” to be the product of its mass and its velocity (what physicists now call “momentum”). Note that “quan- tity of motion,” like velocity, is a vector quantity. That means it has both a mag- nitude, or amount, and a direction. ii For example, the speed of an object is the magnitude of the object’s velocity, but to fully specify the velocity you must state both the speed and the direction of the object’s motion. Newton proceeded to define three different kinds of “force.” The first of these he called the “inherent force of matter” or the “force of Inertia.” He defined this force as the power of a body to resist changes to its motion. This resistance is proportional to the mass of the body, so as noted above mass measures resistance to change in motion. We no longer think of Inertia as a force, but for Newton a force was something that helped determine an object’s motion. As we will see, the Inertia of an object plays an important role in determining how the object will move, so Newton treated it as a force. Newton’s other two forces were “impressed force” and “centripetal force.” Impressed force is anything that acts on a body to change the body’s motion. - T. Crouch(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

Chapter 2 Dynamics 2.1.Newton's Laws of Motion Dynamics is concerned with the relationships between force, mass, energy and motion. For Engineering applications, except those dealing with nuclear and fast moving electron phenomena, the Newtonian model of mass, space, time and force is adequate. Newton (1642 - 1727) in his Philosophiae Naturalis Prinoipia Mathem-atical of 1687 enunciated three laws or axioms relating force and motion which can be stated as follows: 1 A particle will continue in a state of rest, or of uniform motion in a straight line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it. 2 A change of motion with respect to time is proportional to the motive force impressed. 3 For every force acting on a particle, there is a corresponding force exerted by the particle. These forces are equal in magnitude, but opposite in direction. The first law implies the existence of an Inertial frame of reference. Consider the following hypothetical experiment. Erect a set of co-ordinate axes in deep space remote from any other matter and project a particle successively along each axis. If the axes are not accel-erating and not rotating, then the force free motion will persist along the axis which it was projected. Such a set of axes is said to be Inertial. No set of axes is truly Inertial, but a set of axis fixed in the f fixed' stars are very nearly Inertial and must be used, for example,in space ballistics. For most Engineering applications forces can be predicted assuming that a reference frame fixed in the earth is Inertial. In this text the Inertial reference is always designated 1. The motion of the second law is measured by the momentum of the particle, which is the product of its mass and Inertial velocity.Thus, by Newton's second law 38- eBook - PDF

The Principia: The Authoritative Translation and Guide

Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

- Sir Isaac Newton(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

With the elimination of the force, Newton's concept became the standard of classical physics. When Newton introduced the term Inertia he did not know who had in-troduced this term into the study of motion, presumably because neither Mersenne nor Descartes had mentioned Kepler in this context. Some years after the publi-cation of the Principia, however, Newton was criticized by Leibniz (in the latter's Theodicee} for having taken this concept from Kepler, 35 who had indeed used the term Inertia in relation to physics. But Kepler argued for the position disdained by Descartes, that because of the inertness of matter, a body would come to rest wherever it happened to be when the moving force ceases to act. When Newton read Leibniz's criticism, he folded the corner of the page of his personal copy of the Theodicee to mark the lines in question. He also entered into his own copy of the Principia a proposed emendation of def. 3. He would now add a sentence reading: I do not mean Kepler's force of Inertia by which bodies tend toward rest; rather, he meant the force of remaining in the same state, whether of resting or of moving. In the event, he decided that this alteration was unnecessary. 36 33. Janus Faces (§3.1, n. 10 above). 34. I am happy to be able to advance this additional argument in support of Prof. Dobbs's new dating of De Gravitatione. 35. I. B. Cohen, Newton's Copy of Leibniz's Theodicee, with Some Remarks on the Turned-Down Pages of Books in Newton's Library, his 73 (1982): 410-414. 36. Ibid. 1 0 1 102 G U I D E : C H A P T E R 4 4.9 Impressed Force; Anticipations of Laws of Motion (Def. 4) In the presentation of his concept of impressed force, in def. 4, Newton once again makes use of a traditional (this time a late medieval) concept, but again in a wholly novel way. Impressed force is said to be the action—and only the action—that is exerted on a body to change its state, whether a state of rest or of motion. - No longer available |Learn more

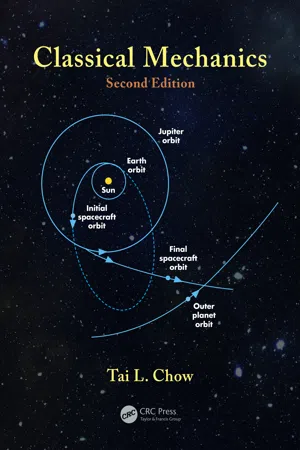

- Tai L. Chow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

25 © 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Newtonian Mechanics The foundation of Newtonian mechanics is the three laws of motion that were postulated by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) as a result of the combination of experimental evidence and a great deal of intuition. 2.1 THE FIRST LAW OF MOTION (LAW OF Inertia) Newton’s first law of motion describes the behavior of a body that has no net outside force acting on it. This law may be stated as follows: A body remains in a state of rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless it is compelled to change that state by an applied force. This contradicts the view of motion held by Aristotle, the Greek philosopher who lived in 340 B.C. He said that the natural state of an object was to be at rest and that it moved only if driven by a force. Was Aristotle right? We all observe that moving objects tend to slow down and come to rest. But this is because of friction. If friction is negligible, a body in motion will remain in motion. Galileo Galilee (1564–1642) first observed this. Rather than rely solely on intuition and general observation as Aristotle did, Galileo tested his ideas with carefully designed experiments and started the mod-ern chain of development in the study of motion. Galileo used two smooth inclined planes set end-to-end, one tilted down and the other up, and released balls of different weights, from rest, down the first inclined plane. (It is similar to that of balls falling vertically, but it is easier to observe because the speeds are slower.) When a ball was released and moved down the first inclined plane, it swept past the bottom and ascended the second inclined plane to about the same height (a little less—fric-tion cannot be eliminated completely) regardless of the tilt of the second plane. He also observed that when the angle of the incline of the second plane was made less steep, the ball slid farther in the horizontal direction (Figure 2.1). - eBook - PDF

Kant's Construction of Nature

A Reading of the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science

- Michael Friedman(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Indeed, it is only in the Mechanics that the schematized concepts of causality and force come fully into play. In par- ticular, our passage from the beginning of the general remark introducing the “ moment of acceleration” (551) concludes by stating that “the possibil- ity of acceleration in general, by means of a continued moment thereof, rests on the law of Inertia” (551). Galilean free fall produced by the earth’s gravity, for example, depends on conserving earlier finite velocities as new infinitesimal velocities are instantaneously added (as moments of accel- eration). And, even more obviously, the action of (universal) gravitation producing the curvilinear orbital motions in the heavens depends on the Inertial tendency of these same bodies to proceed rectilinearly along a tangent. The main point of the general remark, finally, is that the action of the fundamental force of repulsion is to be assimilated, in this respect, to the (continuous and incremental) action of (universal) gravitation. In the context of the Mechanics, therefore, it is the law of Inertia that first makes time determination possible. It does so, in general, by telling us where a moving body would end up in space and time if no dynamical forces acted on it after (or before) a given instant. The effect over time of a continuously acting dynamical force can then be derived from its instantaneous actions (solicitations resulting in moments of acceleration) together with the law of Inertia. In this sense, the law of Inertia binds together different and otherwise independent moments of time by spe- cifying the naturally persisting state of motion of a body on the basis of which changes of state – due to the actions of external forces – can then be determinately ordered. 176 Kant suggests just this kind of role for the law of Inertia, moreover, in the continuation of the passage from the second analogy (A206–7/B252) quoted above. - eBook - PDF

- David H. Eberly(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The equations of motion F = ma will be used to establish the path of motion for an object by numerically solving the second-order differential equations for position. Each of the vector quantities of position, velocity, and acceleration is measured with respect to some coordinate system. This system is referred to as the Inertial frame. If x = (x 1 , x 2 , x 3 ) is the representation of the position in the Inertial frame, the components x 1 , x 2 , and x 3 are referred to as the Inertial coordinates. Although in many cases the Inertial frame is considered to be fixed (relative to the stars as it were), the frame can have a constant linear velocity and no rotation and still be Inertial. Any other frame of reference is referred to as a nonInertial frame. In many situations it is important to know whether the coordinate system you use is Inertial or nonInertial. In particular, we will see later that kinetic energy must be measured in an Inertial system. 2.4 Forces A few general categories of forces are described here. We restrict our attention to those forces that are used in the examples that occur throughout this book. For example, we are not going to discuss forces associated with electromagnetic fields. 32 Chapter 2 Basic Concepts from Physics 2.4.1 Gravitational Forces Given two point masses m and M that have gravitational interaction, they attract each other with forces of equal magnitude but opposite direction, as indicated by Newton’s third law. The common magnitude of the forces is F gravity = GmM r 2 (2.46) where r is the distance between the points and G . = 6.67 × 10 −11 newton-meters squared per kilogram squared. The units of G are selected, of course, so that F gravity has units of newtons. The constant is empirically measured and is called the universal gravitational constant. - Raymond Serway, John Jewett(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Therefore, air resistance plays a major role in the motion of the ball, as evidenced by the variety of curve balls, floaters, sinkers, and the like thrown by baseball pitchers. Summary › Concepts and Principles A particle moving in uniform circular motion has a centripetal acceleration; this acceleration must be pro- vided by a net force directed toward the center of the circular path. An observer in a nonInertial (accelerating) frame of refer- ence introduces fictitious forces when applying Newton’s second law in that frame. An object moving through a liquid or gas experiences a speed- dependent resistive force. This resistive force is in a direction opposite that of the velocity of the object relative to the medium and generally increases with speed. The magnitude of the resis- tive force depends on the object’s size and shape and on the properties of the medium through which the object is moving. In the limiting case for a falling object, when the magnitude of the resistive force equals the object’s weight, the object reaches its terminal speed. › Analysis Model for Problem Solving Particle in Uniform Circular Motion (Extension) With our new knowledge of forces, we can extend the model of a particle in uniform circular motion, first introduced in Chapter 4. Newton’s second law applied to a particle moving in uniform circular motion states that the net force causing the particle to undergo a centripetal acceleration (Eq. 4.21) is related to the acceleration according to o F 5 ma c 5 m v 2 r (6.1) r v S a c S F S Think–Pair–Share See the Preface for an explanation of the icons used in this problems set. For additional assessment items for this section, go to 1. You are working as a delivery person for a dairy store. In the back of your pickup truck is a crate of eggs. The dairy company has run out of bungee cords, so the crate is not tied down.- eBook - PDF

The Mechanical Universe

Mechanics and Heat, Advanced Edition

- Steven C. Frautschi, Richard P. Olenick, Tom M. Apostol, David L. Goodstein(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

But on a boat, we tend to use our local surroundings in the boat - once again, a collection of objects at rest with respect to one another - as defining our frame of reference, even though the boat moves relative to the earth. Kinematically, motion can be described relative to any frame of reference; the choice of frame is simply a matter of convenience. When one turns from mere kinematic description of motion to dynamics - the laws of motion - one still has great freedom in choosing the frame of reference, but it becomes necessary to distinguish between different categories of frames. Let us define an Inertial frame as one in which Galileo's law of Inertia holds (a body acted upon by no forces moves uniformly in a straight line). It can be shown that if frame S is Inertial, then any *Strictly speaking this would be tnie only if the earth moved exactly in a straight line and did not rotate on its axis. Later we shall find that the earth's rotation gives rise to a small deviation of the stone's trajectory called the Coriolis effect. 4 4 PROJECTILE MOTION: A CONSEQUENCE OF Inertia 63 frame S' with respect to which S moves with constant speed in a straight line is also Inertial. To take the simplest example, if a body has a velocity v in the x direction in frame 5, and 5 moves in the x direction at velocity v a with respect to 5', then the body has velocity v' = v + v 0 in the x direction in frame S'. If v and v Q are constant, then so is v' , and the body wiil obey the law of Inertia in frame S' as well as 5, even though its precise location and velocity will be different in the two frames. Thus the two frames are equivalent for discussing the law of Inertia. The equivalence still holds for objects and reference frames moving in different directions as long as their velocities are constant, as we shall show in Chapter 9 . Any Inertial frame is suitable to describe the motion; none is preferred over any other.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.