Physics

Plancks Law

Planck's Law describes the spectral distribution of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body at a given temperature. It states that the energy of the radiation is quantized and is directly proportional to its frequency. This law played a crucial role in the development of quantum theory and provided a foundation for understanding the behavior of light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Plancks Law"

- eBook - PDF

- D. Ter Haar(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

PART I This page intentionally left blank C H A P T E R I The Black Body Radiation Law IT IS well known that a study of the black body radiation led Planck to the introduction of the quantum of action which then, through the work of Einstein, Bohr, Schrodinger and Heisenberg, was extended into modern quantum mechanics. The story of how Planck was led to the radiation law which bears his name has often been told (Rosenfeld, 1936; Einstein, 1951; Whittaker, 1954; Klein, 1962) and is also recounted by Planck himself, both in his Nobel Lecture (1920) and in personal reminiscences written, when he was eighty-five (Planck, 1943; see also Planck, 1949), to preserve for posterity the reasoning which led to the radiation law. However, it is instructive to compare these reminiscences with the many papers written by Planck between 1896 and 1900 (all Planck's papers were collected and reprinted on the occasion of the centenary of his birth (Planck, 1958) and are thus more or less readily available) as the development of Planck's ideas was not quite as uneventful as he remembered it to be.f In the last half and especially the last decade of the nineteenth century, a great deal of effort was concentrated, both experi-mentally and theoretically, on finding out how the energy of the 1 This is also hinted at by von Laue in the preface to Planck's Collected Papers. Especially the importance of KirchhofTs law that the radiation spectrum is independent of the nature of the black body, which Planck gives as the guiding principle of his investigations both in his Nobel Lecture and in the 1943 paper, is not referred to by him in any of his earlier papers on the subject, but only in the 1899 paper (Planck, 1899), which was later condensed by him together with four others in a paper in the Annalen der Physik (Planck, 1900a). Planck's own account of the developments has been repeated by Rosenfeld (1936), who bases his account clearly on Planck's Nobel Lecture. 3 - eBook - PDF

- Ian Duck, E C George Sudarshan(Authors)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

And even with the hindsight of 43 years, reflecting on his discovery at age 85 in wartime Berlin [6], Planck could barely explain his insight more deeply than at the first instant. It was done, he tells us, as a necessary first stratagem to define an entropy for the radiation field in terms of the probability of thermodynamic states, as dictated by Boltzmann. Probabilities, he decided, can be calculated only for discrete and countable alternatives. Planck's Blackbody Energy Spectrum is the energy density U of the radiant heat in the 'Hohlraum' or cavity of a furnace, as a function of the frequency / or the wavelength A = c/f of the radiation and of the equilibrium temperature T of the furnace walls (assumed emitting and absorbing at all wavelengths), the heating element, and the radiation, all monitored through a peep-hole and measured by bolometers. The result we all know (in terms of ft = h/2ir, the photon energy E and momentum p with E = cp= hu = hf) is: I f hf f°° f°° U =WJ WdP **P{hf/' iT) < (1) where the spectral densities are defined as ,_,. Snh f z 8irh 1 M / ( T ) = -^ -e f c / / t T _ 1 a n d U *( T ) = ^ s ^ T A f c T T T ' < 2 > which involve Planck's constant h, Boltzmann's constant k, and the speed of light 10 100 Years of Planck's Quantum c. The integral gives Stefan's Law 87T 5 fc 4 U = ° T With = I5SV-(3) The peak in the energy distribution u/(T) occurs at f m with ^h = 2-8214, kT and that in u(T) at A m with he m kT = 4.9651. At frequencies large compared to / m , the exponential term in the spectral density dominates and Planck's distribution reduces to Wien's speculated result: Einstein was to explain this [3] as the result of high energy photons undergoing only quasi-elastic scattering at low temperatures, and retaining their existence almost unchanged, like a classical gas of material molecules. In the opposite limit, Rayleigh's result from classical electrodynamics and equipartition is obtained: «/(r)/«/ ra -> ^fkT. - eBook - PDF

Blackbody Radiation

A History of Thermal Radiation Computational Aids and Numerical Methods

- Sean M. Stewart, R. Barry Johnson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Planck initially achieved his correct form for Kirchhoff’s universal function using what has undoubtedly become one of the most famous and produc- tive interpolations ever made in the history of theoretical physics. By taking Wien’s radiation law, a result known to be valid in the short wavelength, low temperature limit, together with Lord Rayleigh’s classical result from June 1900 and known to be valid in the long wavelength, high temperature limit, and interpolating between the two, by October 1900 [510] Planck was able to arrive at, at least mathematically to begin with, a form for the radiation law that now bears his name [511, 518]. While Planck had an equation which seemed to fit all known experimental data better than any of the previously proposed distributions laws, particularly at the high temperature, long wave- length limit, it lacked physical justification. After what he later described as the most intense period of work in his life, by December 1900 he had a physically plausible theory to back his earlier result obtained through inter- polation [512, 519]. Finessing his ideas the following year [513, 514, 515] it is now known as Planck’s law for thermal radiation and has held up to all subsequent experimental scrutiny [58, 570, 672, 575, 576, 621, 151]. In modern 12 Blackbody radiation form his law takes the form M b e,λ (λ,T ) = 2πhc 2 λ 5 exp hc k B λT − 1 . (1.19) Here the fundamental constants c, h, and k B are the speed of light in vacuo, Planck’s constant, and Boltzmann’s constant respectively. 17 Developing his law required Planck to introduce the latter two new fundamental constants of nature. 18 While the Stefan–Boltzmann and Wien displacement laws antedate Planck’s formulation, as we will show in Chapter 2, both are direct conse- quences of the latter’s law. - G. J. Tallents(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

4 Radiation Emission in Plasmas In this chapter we initially concentrate on radiation in thermal equilibrium. We derive the Planck radiation law for an equilibrium radiation field by considering the density of photons in a black-body cavity. As well as being applicable to many astrophysical and some laboratory plasmas, the concept of a radiation field in ther- mal equilibrium is useful in deducing the relationships between inverse processes interacting with a radiation field. The three possible radiative processes (spon- taneous emission, photo-excitation and stimulated emission) between two quan- tum states in an atom or ion in the presence of an equilibrium radiation field are examined. It is shown that a simple thought experiment, where the rates of the three radiative processes are in balance with an equilibrium radiation field, leads to universal relationships between the radiative rates. 4.1 The Planck Radiation Law If the radiation and electrons in a medium have many interactions through emission and absorption, the radiation field becomes thermalised and can be regarded as having a temperature equal to that of the electrons. In this section, we calculate the form of the thermalised radiation known as the Planck radiation intensity. An equilibrium radiation field is a collection of photons which follow the rules of statistical mechanics for a collection of bosons. We need to calculate the density of modes for light in a steady-state system. We imagine a cube in space with perfectly conducting (and hence perfectly reflecting) walls and sides of length L. Such a volume with an assumed radiation energy in equilibrium with the walls is known as a black-body cavity (though in inertial fusion work the German word hohlraum is often used). 80- eBook - PDF

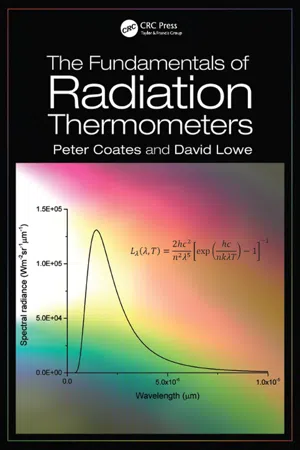

- Peter Coates, David Lowe(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Experimental confirmation was provided in 1958 by the Dutch physicist Sparnaay. At very low temperatures, there is a residual force F given by F = hA 2 d 4 where h is Planck’s constant, A is the area of the plates and d their separation. The form of this equation is that predicted from the spectral distribution of the zero-point field postulated above. 2.8 DEVIATIONS FROM PLANCK’S LAW There are of course many practical problems in the construction of black-body cavities which aim to provide a close approximation to the ideal and which are required for the most critical measurements. Here we just note that the assumptions made in the theoretical derivation of Planck’s law are not always valid, and may give rise to detectable errors. In particular, it should be noted that it has been assumed that the wavelengths of black-body radiation are much smaller than any critical dimension of the cavity. When this is not the case, the mode distribution can no longer be taken as continuous, and the effects of a discrete distribution must be estimated. These may not only affect the Planck and Stefan-Boltzmann laws, but may significantly increase the mean square fluctuations of the radiation field when the mode distribution is irregular. As a result there are two requirements upon the dimensions of the cavity for the effects to remain negligible for most radiometric applications. The first is that the smallest significant dimension of the cavity, d , should be about one hundred times greater than the wavelength being measured. While this condition is almost always found in conventional radiation thermometry, it is not the case of course at millimetre and microwave wavelengths. The second is that the spectral bandwidth - eBook - PDF

Let There Be Light: The Story Of Light From Atoms To Galaxies (2nd Edition)

The Story of Light from Atoms to Galaxies

- Alex Montwill, Ann Breslin(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

‘Atoms of Light’ — The Birth of Quantum Theory 329 e b/ λ T as a series expansion, it is seen that the two expressions merge at long wavelengths. Planck first presented his formula as a ‘comment’ to the German Physical Society at its meeting on 19 October 1900. The title of his comment was simply ‘On an improvement of Wien’s Radiation Law’, and it was presented more as a guess than a statement of physical significance. Nevertheless it seemed to be the correct expression. Heinrich Rubens and Ferdinand Kurlbaum, two German physicists who had made a series of careful measurements on the blackbody spec-trum, worked through the night following the Academy session and compared their experimental results with the formula. They reported complete agreement. As Planck himself later admitted, such experimental verification was crucial: ‘Without the intervention of Rubens the foundation of quantum theory would have perhaps taken place in a totally different manner, and perhaps even not at all in Germany.’ Trying to crack the code The next step was much more difficult. Fiddling with mathe-matical expressions is one thing, deriving the ‘correct’ formula from fundamental principles is a different matter altogether. What were the hidden physical principles that led to the radia-tion spectrum given by the inspired guess formula? Planck tried everything he could on the basis of classical laws, but without success. These laws were tried and tested, and yet just did not lead to the perfectly matching formula for black-body radiation! Nature’s secret At this time many natural philosophers were of the opinion that all major questions in science had been answered. All that It works, but why??? 330 Let There Be Light 2nd Edition remained were a few ‘loose ends’ and perhaps some more sig-nificant figures in the determination of the values of fundamen-tal physical constants. The blackbody radiation spectrum was one of those loose ends. - eBook - PDF

Statistical and Thermal Physics

An Introduction

- Michael J.R. Hoch(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

285 C H A P T E R 15 Photons and Phonons— The “Planck Gas” 15.1 INTRODUCTION In 1900, Max Planck introduced the concept of the quantum of elec-tromagneticradiation,latercalledthephoton,intophysics.Hedidthis to explain the spectral properties of electromagnetic radiation emitted throughasmallaperturebyaconstant-temperature“blackbody”enclos-ure. This marked the start of quantum physics, which led to the devel-opmentofquantummechanicsinthe1920s.Theenergy e ofaphotonof frequency v isgivenbyPlanck’sfamousexpression, ε = h v ,oralternatively ε = ħω ,where ω istheangularfrequency. Inside a constant-temperature enclosure, photons are continually absorbedandemittedbythewalls.Thenumberofphotonsintheenclo-sureisnotfixedbutfluctuatesaroundsomeaveragenumberforanycho-sen frequency. This fluctuation in the number of photons represents an important difference from the situation in the fermion and boson sys-temsconsideredinChapters13and14,wherethenumberofparticles N isfixed.Thechemicalpotentialforphotonsisnotdefinedbecausethere isnoconstrainton N .Itfollowsthat μ shouldbeomittedinthephoton distribution,andthisisshowninSection15.3.Photonshavespin1and are bosons. Because they travel at the speed of light, there are two and notthreeallowedspinorientations.Classically,electromagneticradiation is considered to be a transverse wave with two polarization directions. 286 ◾ Statistical and Thermal Physics: An Introduction Putting μ = 0 in the Bose–Einstein distribution given in Equation 14.1 leadstothePlanckdistributionforphotons, uni3008 uni3009 n e e r r r = -= -1 1 1 1 be b w planckover2pi , (15.1) where ε r istheenergyofphotonsinstate r .For βε r ≪ 1,theaveragenumber ofphotonsfoundinstate r becomesverylargebecausethedenominatorin Equation15.1becomesverysmall. - eBook - ePub

Let There Be Light

The Story of Light from Atoms to Galaxies

- Alex Montwill, Ann Breslin(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

hf.Up to then, an inherent understanding in natural philosophy was that there are no restrictions on the possible values of physical entities. The suggestion that Nature is not continuous was so reactionary that Planck was afraid to publish his hypothesis, and it was in fact not generally accepted until the successful work of Niels Bohr in 1913. Physicists were reluctant to abandon long-established beliefs, with some notable exceptions, such as Albert Einstein, who in 1905 had developed the concept of quantisation even further in his theory of the photoelectric effect.To follow this chapter in detail, some knowledge of basic mechanics and thermodynamics is helpful, but the reader should get a good feeling for the concepts by skimming through the more detailed parts of the discussion, particularly in Section 11.2. When you come to Sections 11.5.1–11.5.4, again skim through the mathematical discussion. If you are comfortable with the mathematics, however, you should enjoy following Planck's footsteps to one of the most fundamental discoveries in the history of physics….11.1 Emission of energy by radiation11.1.1 How does matter emit electromagnetic energy?Matter consists of atoms and molecules containing protons and electrons, which respectively have positive and negative charge. There is always electrical activity even in an electrically neutral piece of matter, because of atomic oscillators whose motion becomes more rapid with increasing temperature. As predicted by Maxwell, and verified by Hertz in 1888, oscillating charges emit electromagnetic waves and in the process lose energy and slow down. That is one way in which a hot surface may cool down by radiating light into the space around it. Eventually, thermal equilibrium is established when the average energy emitted per second is balanced by the radiation absorbed. - eBook - PDF

Einstein's Other Theory

The Planck-Bose-Einstein Theory of Heat Capacity

- Donald W. Rogers(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

(This derivation deviates from Planck’s original work [Planck 1900] for the purpose of simplicity). The Planck equation is written in several different forms, among them, u ( , T ) = 8 h 3 c 3 1 ( e h / k B T − 1 ) (4.5.26) or d E = V ¯ h 3 2 c 3 d ( e ¯ h / k B T − 1 ) , (4.5.27) THE PLANCK EQUATION 67 where ¯ h = h / 2 and V is the volume of the blackbody, or ( , T ) d = 8 h 3 c 3 d ( exp ( h / k B T ) − 1 ) (4.5.28) where exp ( x ) = e x , and is a common alternative notation for the energy density. In terms of wavelength, u ( , T ) = 8 hc 5 1 ( e hc / k B T − 1 ) (4.5.29) 4.6 Immediate Deductions from Planck’s Law Just prior to his presentation of the radiation law in its finished form, Planck had published an empirical equation u ( , T ) = A 3 ( e B / T − 1 ) (4.6.1) as the last stepping stone to his great theoretical triumph. The experimen-talists Rubens and Lummer and Pringsheim quickly verified the close fit between Planck’s empirical form and experimental data. Comparing the theoretical and empirical forms, u ( , T ) = 8 2 c 3 h ( e h / k B T − 1 ) and u ( , T ) = A 3 ( e B / T − 1 ) , makes it evident that A = 8 h / c 3 and B = h / k B . Thus from the para-meter A , extracted from the experimental data, and the speed of electro-magnetic radiation, c , which was well known at the time, Planck obtained the numerical value for the universal constant h that we now call Planck’s constant. This value evolved somewhat as more accurate and extensive experimental data were gathered, but it was quite accurate even in the beginning. Data available in 1899 led to 6 885 × 10 − 27 erg s. By 1900, it was fitted as 6 55 × 10 − 27 erg s. The modern value is 6 626 × 10 − 27 erg s (modern units 6 626 × 10 − 34 J s). Once having the value of h , and the empirical curve fit for B , B = h / k B was solved for k B . Planck’s value of 1 346 × 10 − 16 erg deg − 1 was much superior to previous estimates. - eBook - PDF

- Pierluigi Zotto, Sergio Lo Russo, Paolo Sartori(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Società Editrice Esculapio(Publisher)

The comparison with the experimental measurement is dramatic: the two curves agree only at very low frequencies and while the experimental law shows an energy density going asymptotically to zero at infinite frequency, Rayleigh-Jeans’ law diverges as it approaches the ultraviolet region. It could be thought that some calculation mistake has been done, but the determination of the law is perfectly coherent with classical theory and Boltzmann statistics which gov- erns it. In order to reach an agreement between experiment and theory, it is therefore man- datory to modify some basic concepts and assumptions. 19.4 Planck’s Law The average energy of an oscillator has been obtained by using the equipartition theo- rem, which is a consequence of Boltzmann statistics applied to a homogeneous, isotropic system kept at constant and uniform temperature. The solution of the problem presented by the evaluation of a blackbody law requires the knowledge of how the available energy is distributed among the oscillators, so a statistical approach is needed. In Thermodynamics, the measurement of a temperature corresponds to the evaluation of an index of the average energy which is associated with a macro-state of a system. How- ever, any macro-state can be obtained by combining several micro-states, assuming a dif- ferent energy distribution among them, of the elements that compose a thermodynamic sys- tem and that, in the case at hand, are coupled harmonic oscillators. u ν ν Rayleigh-Jeans’ law experimental curve Chapter 19 Introduction to Quantum Physics 359 which multiplied by the number of oscillators in the spherical shell provides the average in which the number of elements N and the total energy U are constant. The total energy of the system can be obtained by various combinations of the energy associated with any system element once some statistical rules are decided. - eBook - PDF

- S. M. Blinder(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

A theory with such disagree- ments with observation, which classical physics could not reconcile, is said to suffer from an “ultraviolet catastrophe.” 10 1 The Old Quantum Theory Max Planck in 1900 derived the correct form of the blackbody radiation law by introducing a bold postulate. He proposed that energies involved in absorption and emission of electro- magnetic radiation did not belong to a continuum, as implied by classical theory, but were actually made up of discrete bundles, which he called “quanta.” On this basis, Planck is tra- ditionally regarded as the father of quantum theory. A quantum associated with radiation of frequency is proposed to carry an energy = ℎ , (1.2) where the proportionality factor ℎ = 6.626 × 10 −34 J sec is known as Planck’s constant. Using the relation between frequency and wavelength = , (1.3) where = 2.9979 × 10 8 m/sec, the speed of light, we can alternatively express Planck’s formula in terms of wavelength: = ℎ . (1.4) Our development of the quantum theory of atoms and molecules will make extensive use of Planck’s iconic formula. Planck realized that the fatal flaw was equipartition, which is based on the assumption that the possible energies of each oscillator belong to a continuum (0 ≤ < ∞). If, instead, the energies of an oscillator of wavelength come in discrete bundles ℎ = ℎ∕, then the possible energies are given by , = ℎ = ℎ∕, where = 0, 1, 2 … (1.5) By the Boltzmann distribution in statistical mechanics, the average energy of an oscillator at temperature is given by ⟨ ⟩ av = ∑ , − , ∕ ∑ − , ∕ . (1.6) More explicitly, ⟨ ⟩ av = ∞ ∑ =0 (ℎ∕) −ℎ∕ / ∞ ∑ =0 −ℎ∕ . (1.7) Mathematica can evaluate this: Therefore ⟨ ⟩ av = ℎ∕ ℎ∕ − 1 . (1.8) This implies that the higher-energy modes are less populated than what is implied by the equipartition principle. - eBook - PDF

- Malcolm Gray(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

If we now eliminate ¯ n with the help of Eq. (1.57), we obtain Planck’s energy distribution function in terms of wavenumber, U k = ¯ hck 3 /π 2 e ¯ hck k B T − 1 , (1.60) where Boltzmann’s constant has been re-labelled as k B to avoid confusion with the wavenum- ber, k. There are a variety of ways of expressing the Planck law, depending on whether we wish to use wavelength, wavenumber, frequency or angular frequency. The general expres- sion for change of variable in calculus of a single variable, f (x )dx = f (y [x ])dy, (1.61) which conserves infinitesimal areas, can be used to re-write the energy density in terms of any one of these quantities, given that we know it as a function of one. For example, in frequency, ν = ω/(2π ) = kc/(2π ), and Eq. (1.61) takes the specific form U ν = U k dk/dν = (2π/c)U k , (1.62) and using Eq. (1.60) with k = 2πν/c, we obtain the Planck law in frequency, U ν = 8πhν 3 c 3 1 (e hν kT − 1) , (1.63) which is a very commonly used version. By differentiating Eq. (1.63), and equating the result to zero, we find that U ν has a turning point. This can be shown to be a maximum, and occurs at a frequency given by the solution of the transcendental equation e y (3 − y ) = 3, (1.64) where y = hν max /(kT ), and ν max is the frequency at which U ν is a maximum. Equation (1.64) is solved for y 2.82, so ν max = 2.82kT /h = 5.88 × 10 10 T Hz, (1.65) which is known as Wien’s displacement law. To find the total energy density of the radiation in the cavity, we can integrate Eq. (1.63) over all frequencies. If we let y = hν/(kT ), we obtain U = ∞ 0 8πhν 3 c 3 1 (e hν kT − 1) dν = 8πk 4 T 4 c 3 h 3 ∞ 0 y 3 dy e y − 1 . (1.66) 16 Introduction r dr dA θ Ray, R Fig. 1.4. A diagram showing the relation between the energy density and specific intensity descriptions of a radiation field. To solve the integral in Eq. (1.66), we can multiply top and bottom by e −y , and then apply the long division method, already used in Eq.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.