Physics

Rayleigh Jeans Law

The Rayleigh-Jeans Law is a formula that describes the spectral radiance of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body as a function of wavelength and temperature. It was developed by Lord Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans in the late 19th century. The law accurately describes the behavior of longer wavelengths but fails at shorter wavelengths, leading to the ultraviolet catastrophe.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Rayleigh Jeans Law"

- eBook - ePub

- Grant R. Fowles(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Dover Publications(Publisher)

7.4 Classical Theory of Blackbody Radiation. The Rayleigh-Jeans FormulaAccording to classical kinetic theory, the temperature of a gas is a measure of the mean thermal energy of the molecules that comprise the gas. The average energy associated with each degree of freedom of a molecule is kT, where k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the absolute temperature. This well-known rule is called the principle of equipartition of energy. It applies, of course, only to systems in thermodynamic equilibrium.Lord Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans suggested that the equipartition principle might also apply to the electromagnetic radiation in a cavity. If the radiation is in thermal equilibrium with the cavity walls, then one might reasonably expect an equipartition of energy among the cavity modes. Rayleigh and Jeans assumed that the mean energy per mode is kT. In effect, this assumption amounts to saying that in a given mode the electric field and the magnetic field each represent one degree of freedom. If there are g v modes per unit frequency interval per unit volume, then the spectral density of the radiation would be g v kT. Hence, from Equation (7.15), we have(7.16)This yields, in view of Equation (7.7), the following formula for the spectral radiance, that is, the power per unit area per unit frequency interval:(7.17)This is the famous Rayleigh-Jeans formula. It predicts a frequency-squared dependence for the spectral distribution of blackbody radiation (Figure 7.5 ). For sufficiently low frequencies the for-mula is found to agree quite well with experimental data. However, at higher and higher frequencies the formula predicts that a blackbody will emit more and more radiation. This, of course, is in contradiction with observation. It is the so-called “ultraviolet catastrophe” of the classical radiation theory. The ultraviolet catastrophe clearly shows that there is a fundamental error in the classical approach.Figure 7.5 . The Rayleigh-Jeans law. The curves of I v versus v - eBook - PDF

Einstein's Other Theory

The Planck-Bose-Einstein Theory of Heat Capacity

- Donald W. Rogers(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Also we have replaced the speed v with the speed c . This is the Rayleigh-Jeans equation. The Rayleigh-Jeans equation is a sound application of the THE PLANCK EQUATION 61 Figure 4.4.1. The Rayleigh-Jeans equation and the blackbody energy density curve calculated and observed at 2000 K. Experimental observations are shown by the lower curve. classical principle of equipartition of energy to electromagnetic radiation within a chamber, but it leads to a completely unacceptable conclusion. If the number of allowed modes of oscillation within a blackbody radiator goes up as the square of the frequency, then the energy and the emitted intensity should also go up as the square of the frequency. If this conclu-sion were correct, the energy within any chamber at T > 0 K would be infinite because the term in 2 has no upper limit. We know that when we look into an ordinary furnace we are not bombarded by X-rays and cos-mic rays of near-infinite energy. We detect radiation mainly in the infrared (heat) with, perhaps, some radiation in the visible range. There must be some damping factor that refuses to allow emission of higher frequencies. We see damping of the Rayleigh-Jeans curve in the experimental behavior shown in the lower curve in figure 4.4.1. The Rayleigh-Jeans equation, like the Wien equation, offers a tantali-zing glimpse of a true theory for blackbody radiation. Its strength is that, unlike the Wien equation, it is rigorously derived from classical physical principles, but its weakness is, quite obviously, that it does not follow the experimental curve as closely as the Wien equation. It best approaches the experimental curve at low frequencies (long wavelengths), which is precisely where the Wien equation fails. Neither of these equations can be simply wrong; both tell us part of the blackbody radiation story. Prior to the Rayleigh-Jeans (1905) derivation, Max Planck had proposed a - eBook - PDF

- Pierluigi Zotto, Sergio Lo Russo, Paolo Sartori(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Società Editrice Esculapio(Publisher)

The comparison with the experimental measurement is dramatic: the two curves agree only at very low frequencies and while the experimental law shows an energy density going asymptotically to zero at infinite frequency, Rayleigh-Jeans’ law diverges as it approaches the ultraviolet region. It could be thought that some calculation mistake has been done, but the determination of the law is perfectly coherent with classical theory and Boltzmann statistics which gov- erns it. In order to reach an agreement between experiment and theory, it is therefore man- datory to modify some basic concepts and assumptions. 19.4 Planck’s Law The average energy of an oscillator has been obtained by using the equipartition theo- rem, which is a consequence of Boltzmann statistics applied to a homogeneous, isotropic system kept at constant and uniform temperature. The solution of the problem presented by the evaluation of a blackbody law requires the knowledge of how the available energy is distributed among the oscillators, so a statistical approach is needed. In Thermodynamics, the measurement of a temperature corresponds to the evaluation of an index of the average energy which is associated with a macro-state of a system. How- ever, any macro-state can be obtained by combining several micro-states, assuming a dif- ferent energy distribution among them, of the elements that compose a thermodynamic sys- tem and that, in the case at hand, are coupled harmonic oscillators. u ν ν Rayleigh-Jeans’ law experimental curve Chapter 19 Introduction to Quantum Physics 359 which multiplied by the number of oscillators in the spherical shell provides the average in which the number of elements N and the total energy U are constant. The total energy of the system can be obtained by various combinations of the energy associated with any system element once some statistical rules are decided. - eBook - PDF

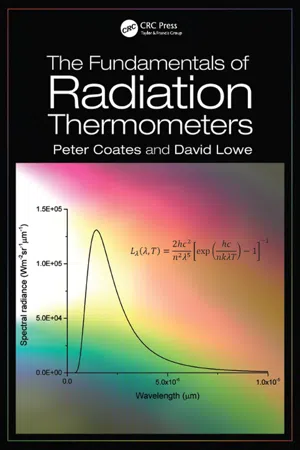

- Peter Coates, David Lowe(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

If the energy levels are closely packed, so that they may be treated as a continuous distribution, and if the energy depends quadratically upon either the Fundamental laws 35 coordinates or the momentum of the particle, then the equation may be integrated to give E = kT/ 2 (2.21) that is, the mean energy for each particle or mode obeying the quadratic require-ment is kT/ 2 . The total energy is therefore made up of a number of equal con-tributions from each relevant mode of motion; this is known as the principle of equipartition of energy. In the case of the radiation field inside a black-body cav-ity, combining this result with the density of modes obtained in (2.15) gives the Rayleigh-Jeans law for the spectral distribution: u ( ν, T ) = 8 πν 3 kT/c 3 (2.22) Clearly this does not predict a maximum in the spectral distribution at any fre-quency or wavelength, and must therefore be incorrect in a general sense. Although it is frequently stated that it does predict the spectral intensity at low frequencies (long wavelengths) and high temperatures, for the purposes of radiation thermom-etry the agreement, as shown in Figure 2.5 , is rather poor. In fact, the main im-portance of the Rayleigh-Jeans law was that it demonstrated that classical physics at the turn of the century could not correctly calculate the spectral distribution of black-body radiation, and that some additional postulates were required. 2.4.2 Quantum statistics We now consider the modification which Planck found necessary in order to pro-vide a theoretical derivation of his empirical equation. Following the Boltzmann technique outlined in the previous section, the distribution of modes (or resonators in the Planck formulation) is divided into groups, each covering a small frequency interval. A given group may contain G i modes, and correspond to an energy E i . At this point Planck followed Boltzmann’s methods very closely. - eBook - PDF

- P C Mehta, V V Rampal(Authors)

- 1993(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

The classical Rayleigh Jeans Law predicts that the energy per unit frequency interval, E(v) dv is determined by E ( t -) d v = (8Tii> 2 kT/c 3 )di> ( 1 . 1 ) and is unbounded as v increases. This leads to ultraviolet catastrophe since total emitted energy E, given by r°° E = E(i>)di> (1.2) J o 2 LASERS AND HOLOGRAPHY is ultraviolet divergent. Wien's law, which has validity at high freguencies, is again unable to explain observations at low freguencies since p(v) = av 3 exp(-|3v/T) ( (1.3) where p(v) is energy density in the freguency interval dv such that E(i>)di> = V p(v) dv. (1-4) V is cavity volume and f3 is Wien's constant. The difficulties of classical representations were overcome by Planck who proposed the energy distribution formula E(v)dv = (87iV/c 3 )hv di> [exp(hy/kT)-l] _l , (1.5) where h is Planck's constant. He assumed that oscillators in thermal eguilibrium have discrete energy levels and not the continuous range associated with classical oscillators. It is easy to see from Eg. 1.5 that for small v, since exp(hi>/kT)-(l + hf/kT) , Eg. 1.5 reduces to Eg. 1.1; for large v, however, it follows Eg. 1.3. The ultraviolet divergence is also removed, since integration of Eg. 1.5 over all freguencies, provides CO E = E(v)di> = (8n 5 /15h 3 c 3 ) (kT) 4 , (1.6) J o which is finite and agrees with Stefan's law E = oT 4 , (1.7) where - eBook - PDF

- K. Ya. Kondrat'Yev(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

The problem of the conditions under wich the local thermodyna-mic equilibrium can exist in the atmosphere was further developed by Woolley 10,11 and Mustel' 12 . However, we shall restrict ourselves to the above schematic considerations of this question, without going into the details of more complex theories. 2. Planck's law. Equation (1.7) representing Kirchhoff' s law contains the function Ε λ , which gives the distribution of the intensity of radia-tion over the spectrum of the black body. The determination of the form of the function Ε λ (Τ) is the fundamental problem of the theory of radiation. One of the first successful attempts to solve it was made by the Russian physicist Mikherson. However, it was Planck who succeeded in finding the completely correct solution based on the THERMAL· RADIATION 11 hypothesis of the quantum character of the radiation process. As we know, Planck's investigations of the distribution of energy over the radiation spectrum of the perfect black body laid the foundations of modern quantum mechanics. The variant of the Ε λ (Τ) function, known as Planck's function, is easily obtained from the result of the preceding section. In fact, on comparing equations (1.17) and (1.9) we find that these equations are identical, if (1.22) and the following relation: efcA = «,^«.^? (ΐ·25) are fulfilled. By dividing (1.25) by (1.22) we obtain p rh — niigjgt) c 2 In the case of local thermodynamic equilibrium the relation (1.15) applies. The last expression can then be written as follows: Changing from the frequency to wavelength, and taking into account the relations we obtain Ε λ άλ = Ε ν άν, v = j and |dA|=^dv FIT 2hc2 * iK ' ~ ~W e hclXkT — 1' (1.27) The last two equations define Planck's function in an explicit form. The values of constants contained in these formulae are as follows: Planck's constant h = 6.624x 10~ 27 erg/sec, the velocity of light c = 2.99790 X10 10 cm/sec, and Boltzmann's constant k = 1.380 X X 10-16 erg/deg. - eBook - PDF

Blackbody Radiation

A History of Thermal Radiation Computational Aids and Numerical Methods

- Sean M. Stewart, R. Barry Johnson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The additional exponential factor was added afterwards to ensure the final distribution function tended to zero in the short wavelength, low temperature regime. Whether his proposed distribution law more closely represented the exper- imental facts Lord Rayleigh was not in a position to say but hoped “. . . the question may soon receive an answer at the hands of the distinguished experi- menters who have been occupied with this subject” [548]. 16 The final solution however, when it came in late 1900, would require a complete conceptual break in how physics up until that time had conceived energy to be. And it was to come from the man who would go on to become one of the greatest theoretical physicists of all time — Max Planck. Planck, as we saw, first turned his attention to the problem of blackbody radiation in 1897. He had initially been drawn to the problem by the uni- versal character of the law required by Kirchhoff’s law. At the time, Planck was almost forty years old and it would have been tempting to think his best work lay behind him. Up until this point he had spent his entire scientific career investigating the second law of thermodynamics and its consequences. The prospect of him solving one of the late nineteenth century’s great un- solved problems seemed remote. After three years of solid effort working on the problem, by the end of 1900, by considering the energy emitted from a blackbody is not continuous but rather discrete and only comes in amounts made up of multiples of some fundamental “quanta,” Planck was finally able to give what later proved to be the correct mathematical description for the spectral radiant exitance of a blackbody valid for all wavelengths. Planck initially achieved his correct form for Kirchhoff’s universal function using what has undoubtedly become one of the most famous and produc- tive interpolations ever made in the history of theoretical physics. - eBook - PDF

- D. Ter Haar(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Pergamon(Publisher)

Planck's own account of the developments has been repeated by Rosenfeld (1936), who bases his account clearly on Planck's Nobel Lecture. 3 4 THE OLD QUANTUM THEORY From this it follows, first of all, that if the spectral distribution shows a maximum at a frequency v m —as was found to be the case experimentally, long before it was proved theoretically—this frequency will shift with temperatures in such a way that W (v,T) = v 3 /(v /r). (1.1) yJT = constant, (1.2) or, if we introduce wavelengths instead of frequencies, l m T = constant, (1.3) which is Wierts displacement law (1893). radiation emitted by a black body was distributed over the various wavelength—or frequencies. The names of Kirchhoff, Wien, Rayleigh and Jeans are closely connected with these developments, as well as that of Planck. A body at a definite temperature T will both emit and absorb radiation. If it absorbs all the radiation incident upon it, it is called a black body. From this it follows (Kirchhoff, 1859) that the radiation emitted by a black body will depend only on its temperature, but not on its nature: if we consider a number of bodies in equilibrium inside a cavity, the walls of which are kept at a constant temperature T, we should reach an equilibrium situation. At equilibrium, the ratio of the radiation of a given wavelength absorbed by one body to the radiation of the same wavelength emitted by the same body should be unity, as otherwise there would not be equilibrium. As the radiation absorbed will be determined by the radiation density in the cavity and hence by its temperature, we find that the radiation emitted by a black body will be a function of T only. We now define u(v, T) dv as the energy density of all radiation components with frequencies between v and v + dv. It is remark-able how much one can find out about u(v, T) from general considerations without considering a specific model. - eBook - ePub

Blackbody Radiation

A History of Thermal Radiation Computational Aids and Numerical Methods

- Sean M. Stewart, R. Barry Johnson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

which he stated was valid in the long wavelength, high temperature limit. The additional exponential factor was added afterwards to ensure the final distribution function tended to zero in the short wavelength, low temperature regime.Whether his proposed distribution law more closely represented the experimental facts Lord Rayleigh was not in a position to say but hoped “…the question may soon receive an answer at the hands of the distinguished experimenters who have been occupied with this subject” [548 ].16 The final solution however, when it came in late 1900, would require a complete conceptual break in how physics up until that time had conceived energy to be. And it was to come from the man who would go on to become one of the greatest theoretical physicists of all time — Max Planck.Planck, as we saw, first turned his attention to the problem of blackbody radiation in 1897. He had initially been drawn to the problem by the universal character of the law required by Kirchhoff’s law. At the time, Planck was almost forty years old and it would have been tempting to think his best work lay behind him. Up until this point he had spent his entire scientific career investigating the second law of thermodynamics and its consequences. The prospect of him solving one of the late nineteenth century’s great unsolved problems seemed remote. After three years of solid effort working on the problem, by the end of 1900, by considering the energy emitted from a blackbody is not continuous but rather discrete and only comes in amounts made up of multiples of some fundamental “quanta,” Planck was finally able to give what later proved to be the correct mathematical description for the spectral radiant exitance of a blackbody valid for all wavelengths.Planck initially achieved his correct form for Kirchhoff’s universal function using what has undoubtedly become one of the most famous and productive interpolations ever made in the history of theoretical physics. By taking Wien’s radiation law, a result known to be valid in the short wavelength, low temperature limit, together with Lord Rayleigh’s classical result from June 1900 and known to be valid in the long wavelength, high temperature limit, and interpolating between the two, by October 1900 [510 ] Planck was able to arrive at, at least mathematically to begin with, a form for the radiation law that now bears his name [511 , 518 ]. While Planck had an equation which seemed to fit all known experimental data better than any of the previously proposed distributions laws, particularly at the high temperature, long wavelength limit, it lacked physical justification. After what he later described as the most intense period of work in his life, by December 1900 he had a physically plausible theory to back his earlier result obtained through interpolation [512 , 519 ]. Finessing his ideas the following year [513 , 514 , 515 ] it is now known as Planck’s law for thermal radiation and has held up to all subsequent experimental scrutiny [58 , 570 , 672 , 575 , 576 , 621 , 151 - eBook - PDF

Fundamentals of Radio Astronomy

Observational Methods

- Jonathan M. Marr, Ronald L. Snell, Stanley E. Kurtz(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Introduction to Radiation Physics ◾ 53 or B T kT ν λ ( ) ≈ 2 2 (2.13) Note how simple this expression is in comparison to the Planck function (Equation 2.5). This expression is very useful, provided you are in the realm where h ν /kT << 1. This expression is known as the Rayleigh–Jeans approximation , often referred to as the Rayleigh–Jeans law . At centimeter wavelengths, most of the time we can use the Rayleigh–Jeans approxima-tion, avoiding the far more complex Planck function. As demonstrated in Problem 9, parts b and c, only at the highest radio frequencies and with observations of cold objects does the approximation start to differ from the full expression. This is one major convenience of working at radio wavelengths. Equations 2.12 and 2.13 are so important in radio astron-omy that you will want to memorize them! Example 2.8: A radio observation at a wavelength of 6.00 cm yields the determination that a par-ticular radio source has a solid angle of 7.18 × 10 −6 sr, is opaque and thermal, and has a flux density of 350 Jy. 1. What is the temperature of the radio source? 2. What is the intensity of this source at 2.70 cm? 3. An observation is made of another opaque, thermal radio source that is twice as hot as the first source. What is its intensity at 2.70 cm? Answers: 1. Since the flux density is measured at 6.00 cm, which is still in the realm where the Rayleigh–Jeans approximation works well, we solve for the temperature using Equations 2.13 and 2.4. F = kT ν λ 2 2 Ω Solving for T gives us T = × ( ) × × × -----3 50 1 0 0 060 2 1 38 10 7 18 24 2 23 . . ( . ) . W m Hz m J K 2 1 1 10 6 -= sr 63.6 K 54 ◾ Fundamentals of Radio Astronomy 2. Again using Equation 2.13, we find that the intensity at 2.70 cm, which is 11.1 GHz, is I 11 1 23 1 2 18 2 2 1 38 10 63 6 0 0270 2 41 10 . . . ( . ) . GHz ( JK ) K m Wm = × = × ----Hz sr --1 1 3.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.