Politics & International Relations

Slavery and the Constitutional Convention

During the Constitutional Convention, the issue of slavery was a contentious topic. Southern states wanted to count slaves as part of their population for representation in Congress, while Northern states opposed this. The Three-Fifths Compromise was eventually reached, counting each slave as three-fifths of a person for both representation and taxation purposes.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Slavery and the Constitutional Convention"

- eBook - PDF

- Gwenda Morgan(Author)

- 2024(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

. . Northern leaders – political, academic, and clerical – consistently ducked the issue that the Revolutionary leaders had insisted must be solved if the nation was to be united . . . Slavery would continue to grow in the South and the problem of slavery would continue to require a national solution. When it came, it brought five times the American casualty rate of the Second World War. 115 With the exception of Finkelman’s and Maltz’s work, studies of slavery and the Constitution, for the most part legalistic and historiographical, gave way in the 1990s to broader works on the American Revolution in which slavery was one issue among others, albeit an important one, or to studies of Antebellum America in which the Constitution served as a prelude to later developments. 116 In Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (1997) which built on much of his THE DEBATE ON THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 156 earlier work, Rakove wryly observed that it was hardly surprising that ‘compromise’ was such a ‘staple theme’ of most narrative accounts of the Federal Convention since ‘in the end, the framers granted concessions to every interest that had a voice’. 117 What was sacrificed, he recognized (like Hildreth) was a moral princi- ple ‘to attain a tangible political end’. It was the second compromise on representation, however, that Rakove saw as ulti- mately the more costly. He shifted attention to the compromise awarding parity of representation to states in the Senate as the more significant of the two compromises over representation. 118 By the time Don Fehrenbacher’s The Slaveholding Republic was posthumously published in 2001, the issue of slavery’s impor- tance at the Convention had to some extent receded. When matters ‘touching slavery’ arose in the Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress, they ‘had been incidental or ancil- lary to some matter or purpose generally considered of greater immediate importance’. - Matthew Mason(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

132 As antislavery activists saw slavery entering politics, they hoped its connection to national interest and reputation would lend a greater urgency to their cause among the otherwise uncommitted.Slavery also showed signs of usefulness on the domestic political front in America after the Revolution. The political serviceability of slavery in all its variety was on full display in the debates surrounding the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution between 1787 and 1789. Many historians have posited the centrality of slavery to the Constitutional Convention and the ratification debates that followed. But for most players, slavery constituted a secondary issue that could be used to great advantage in pressing their respective points of view regarding the primary topics at hand.133This was true at the Philadelphia Convention, where discord between the small and large states concerning representation in the new Congress formed the most important divide. The question of whether to count slaves toward each state’s congressional presence was contentious, but most often it came into play in the context of the larger debate over representation. James Madison famously asserted in his notes of the Convention’s debates that the vital division was not between large and small states, but rather between slave and free states. But a month before he made this characterization, Madison had urged his fellow delegates to set aside the issue of counting slaves for representation, so as not to distract from the real business at hand, proportional representation by population. Indeed, his colleagues agreed that “every thing depended on” whether states would be counted equally or by population. Only after a full month of bruising debate did Madison circle back and suggest that the free state—slave state divergence was the crucial one.134 This suggests that his famous formulation should be taken more as a diversionary tactic than at face value. Furthermore, New Jersey led the fight against slave representation in Philadelphia, a curious stand for a state with one of the largest slave populations in the North.135 Apparently, the delegates from this small state thought that by attacking slave representation, they could effectively undermine the principle of popular representation with which it was bound. On the other hand, delegates from the large state of Massachusetts, later the home of slave representation’s leading foes, were ambivalent on the issue in Philadelphia. As Northern politicians had done in previous debates over counting slaves, they supported it if it increased the South’s tax burden but not if it increased the South’s representation. Some Massachusetts delegates did object to counting slaves, but as a whole the Massachusetts delegation compromised on the issue.136- eBook - PDF

Foreshadows of the Law

Supreme Court Dissents and Constitutional Development

- Bloomsbury Publishing(Author)

- 1992(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Chapter 1 A CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT IN SLAVERY Ratification of the Constitution created a new political union. Even when consisting of only thirteen states, as it did in the immediate aftermath of revolution, the nation comprised many interests and competing priorities. The rivalries, differences and chauvinism of the several states were an im- pediment to but ultimately a reason for establishing a viable national union. Under the Articles of Confederation, which governed the nation in the years immediately after the American Revolution, the federal government had no power over interstate commerce. Minus centralized authority and uniformity of standards, the various states sought to maximize their re- spective advantage by means of taxation, tariffs and other trade barriers. As economic warfare devolved into economic chaos, it became apparent that the fledgling union would not prosper and might not survive without structural revision. A commonly sensed need to enhance national eco- nomic powers soon expanded into inspiration for the Constitutional Con- vention which, in 1787, generated the plan for a new political system. Compromise and the Constitution Not all differences among the states were resolved in the framing and ratification process. Brokering a new nation required compromise, the success of which depended on calculated ambiguity and manipulability of terms. Agreement with respect to the contents of the Constitution thus did not resolve all aspects of the document's meaning or even its general purpose. Even now, perceptions vary with respect to what the Constitu- tional Convention achieved and the charter it produced signifies. For some, 2 Foreshadows of the Law the Constitution is notable as a source of individual rights and liberties that check the exercise of assigned governmental powers. For others, the document is essentially a blueprint of governmental structure and author- ity subject to specific restrictions on official action. - eBook - PDF

- Donald E. Lively(Author)

- 1992(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

Chapter I Constitutional Law and Slavery The finessing of slavery at the republic's inception effectively accom- modated the institution, albeit in terms that obscured the Constitution's connection to it. The calculated bypass, however, deferred rath r than avoided eventual reckoning. Despite Congress's explicit power to ter- minate the import of slaves beginning in 1808, the decision to allow or prohibit the institution itself was left to each state. Even before the ink had dried in Philadelphia, problematic questions pertaining to slavery had materialized. As the nation evolved over the next several decades, effective answers would be increasingly scarce. Original expectations that slavery would die of its own accord, or be satisfactorily reckoned with by the political process, were miscalculated or misplaced. Society instead became ever more deeply immersed in and confounded by the slavery issue. In 1787, the Congress under the Articles of Confederation passed the Northwest Ordinance, which precluded ''slavery... in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." 1 Competing sentiment exists as to whether the enactment represented "a symbol of the [American] Revolution's liberalism" or was "part of a larger, and insidious bargain" constituting "the first and last antislavery achievement by the central government." 2 On its face, and despite inclusion of a fugitive slave clause, the Northwest Ordinance may seem consonant with a sense that slavery was a terminal institution. Some historians, noting that the ordinance was enacted by a southern dominated Congress one day after the three-fifths compromise 12 THE CONSTITUTION AND RACE on apportionment, suggest that the prohibition was an exercise in cal- culated cynicism. - eBook - PDF

Teaching Enslavement in American History

Lesson Plans and Primary Sources

- Chara Haeussler Bohan, H. Robert Baker, LaGarrett J. King, Caroline R. Pryor, Jason Stacy, Erik Alexander, Charlotte Johnson, James Mitchell, Caroline R. Pryor, Jason Stacy, Erik Alexander, Charlotte Johnson, James Mitchell(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

Northerners went along SLAVERY AND THE CONSTITUTION | 101 with it all because in return they got a nation united for commerce and defense and the right to suppress slavery in their own neighborhoods. CITATION: Walter A. McDougal, Freedom Just Around the Corner (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), 317–318. Supporting Question 1 Featured Source G Joe R. Feagin, Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression, 2006 James Madison was a very influential participant at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. According to his unique notes on the meeting, the Convention was scissored across a slave/not slave divide among the delegations. At that critical gathering, the learned Madison represented those who felt the enslavement of African Americans was essential to the country’s economic prosperity. Slavery was an important issue in the debates, and the new Constitution—under Madison’s watchful eye— carefully protected the interests of slaveholders in numerous provisions including (1) Article 1, Section 2, which counts an enslaved person as only three-fifths of a person; (2) Article 1, Section 2 and 9, which apportions taxes on the states using the three-fifths formula; (3) Article I, Section 8, which gives Congress authority to suppress slave and other insurrections; (4) Article I, Section 9, which prevents the slave trade from being abolished before 1808; (5) Article 1, Section 9 and 10, which exempts goods made by enslaved workers from export duties; (6) Article 4, Section 2, which requires the return of fugitive slaves; and (7) Article 4, Section 4, which stipulates the federal gov- ernment must help state governments put down domestic violence, including slave uprisings. Such constitutional provisions reveal close linkages between the economic exploitation of African Americans and other key institutions such as the legal system and federal and state governments. - eBook - PDF

Entrenchment

Wealth, Power, and the Constitution of Democratic Societies

- Paul Starr(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

These Racial Slavery as an Entrenched Contradiction 72 developments directly implicated southern interests. As a region dependent on exports of its agricultural products, still struggling to defeat powerful native tribes, and looking toward opportunities be-yond the Appalachians, the South would benefit from a stronger federal government. Like their northern counterparts, southern elites were also concerned about threats to property that they discerned in the movements among hard-pressed farmers, who sought to weaken obligations to repay debts under state law. 31 Compared with the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution vastly increased the national government’s fiscal, military, judicial, and other powers. Therein, from the South’s standpoint, also lay the danger. A federal government whose laws were supreme might someday give antislavery forces the power to abolish slavery throughout the nation. The rising tide of emancipation in the North also alarmed slaveholders. Consequently, the South’s representatives were determined to limit federal authority even as they expanded it, and to obtain sufficient representation in the new government to protect slavery and other sectional interests. As it turned out, no effort materialized at the Constitutional Convention to emancipate the nation’s slaves, though the conven-tion did lay the ground for an end to the international slave trade. Deeming it tactically unwise, Benjamin Franklin, at the time presi-dent of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, decided not to present its petition to the convention. In the interests of forging an agree-ment, the representatives who personally opposed slavery gave pri-ority to the nationalist aims that northerners and southerners shared. Not for the last time, the interests of black people were sacrificed in the name of compromise and national unity. Conse-quently, the Constitution does not deal at length with slavery; indeed, the words “slavery” and “slaves” never appear in it. - Steven Wheatley(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Hart Publishing(Publisher)

208 The prohibition on slavery is now recognised as an international norm of jus cogens standing; the preamble of the 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery refers to ‘freedom [as] the birthright of every human being’. 209 In the period before the establishment of the League of Nations, there was a decline in the power of the idea of human rights, with neither the German Empire under the Constitution of 1871, nor the French Third Republic Constitution of 1871 containing clauses on the fundamental rights of the citizen. 210 International human rights emerged in the period following what the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Constitution describes as the ‘great and terrible war’ of 1939–45, made possible ‘by the denial of the democratic princi-ples of the dignity, equality and mutual respect of men’. 211 International human rights formed one part of the constitutional settlement reflected in the adoption of the Charter of the UN, although elements of the right of peoples to self-determination 212 and the protection of minorities had been present in the settlement that followed World War I. 213 The recogni-tion of universal (at least globalised) human rights norms represents an important shift in the nature of international law that accords recognition and rights to human persons. State law systems are subject to the international law order (at least in relation to fundamental rights). The change is reflected most dramatically in the Nuremberg Charter and decision of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg) (IMT), which 207 Article 2(a) of the Slavery Convention, International Convention to Suppress the Slave Trade and Slavery (25 September 1926), 46 Stat 2183. 208 Article 2(b) ibid. 209 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institu-tions and practices Similar to Slavery (1956) 226 UNTS 3 preamble.- William M. Wiecek(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cornell University Press(Publisher)

3Slavery in the Making of the Constitution

The Confederation Congresses had demonstrated that decisions concerning slavery could be incorporated into national policy making without disturbing the federal consensus. But the inadequacies of national authority under the Articles led nationalists to work for a change in the constitutional basis of the American federation, and this provided an opportunity for some slave-state representatives to establish slavery more securely under national authority. As a result of their efforts, the Philadelphia Convention inserted no less than ten clauses in the Constitution that directly or indirectly accommodated the peculiar institution. They were:1. Article I, section 2: representatives in the House were apportioned among the states on the basis of population, computed by counting all free persons and three-fifths of the slaves (the “federal number” or “three-fifths” clause);2. Article I, section 2 and Article I, section 9: two clauses requiring, redundantly, that direct taxes (including capitations) be apportioned among the states on the foregoing basis, the purpose being to prevent Congress from laying a head tax on slaves to encourage their emancipation;3. Article I, section 9: Congress was prohibited from abolishing the international slave trade to the United States before 1808; 4. Article IV, section 2: the states were prohibited from emancipating fugitive slaves, who were to be returned on demand of the master; 5. Article I, section 8: Congress was empowered to provide for calling up the states’ militias to suppress insurrections, including slave uprisings; 6. Article IV, section 4: the federal government was obliged to protect the states against domestic violence, again including slave insurrections; 7. Article V: the provisions of Article I, section 9, clauses 1 and 4 (pertaining to the slave trade and direct taxes) were made unamendable;8. Article I, section 9 and Article I, section 10: these two clauses prohibited the federal government and the states from taxing exports, one purpose being to prevent them from taxing slavery indirectly by taxing the exported products of slave labor.- eBook - ePub

Slavery and the Founders

Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson

- Paul Finkelman(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

106 The costs Wilson worried about were more financial than moral.The word “slavery” was never mentioned in the Constitution, yet its presence was felt everywhere. The new wording of the fugitive slave clause was characteristic. Fugitive slaves were called “persons owing service or Labour,” and the word “legally” was omitted so as not to offend northern sensibilities. Northern delegates could return home asserting that the Constitution did not recognize the legality of slavery. In the most technical linguistic sense, they were perhaps right. Southerners, on the other hand, could tell their neighbors, as General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney told his, “We have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge, which is a right we had not before.”107Indeed, the slave states had obtained significant concessions at the Convention. Through the three-fifths clause they gained extra representation in Congress. Through the electoral college their votes for president were far more potent than the votes of northerners. The prohibition on export taxes favored the products of slave labor. The slave trade clause guaranteed their right to import new slaves for at least twenty years. The domestic violence clause guaranteed them federal aid if they should need it to suppress a slave rebellion. The limited nature of federal power and the cumbersome amendment process guaranteed that, as long as they remained in the Union, their system of labor and race relations would remain free from national interference. On every issue at the Convention, slave owners had won major concessions from the rest of the nation, and with the exception of the commerce clause they had given up very little to win these concessions. The northern delegates had been eager for a stronger Union with a national court system and a unified commercial system. Although some had expressed concern over the justice or safety of slavery, in the end they were able to justify their compromises and ignore their qualms. - eBook - PDF

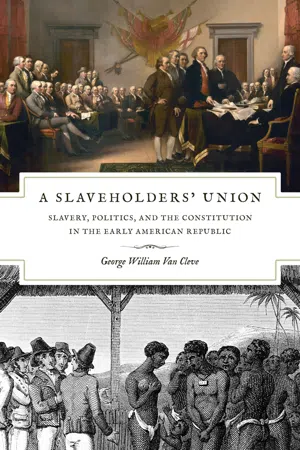

A Slaveholders' Union

Slavery, Politics, and the Constitution in the Early American Republic

- George William Van Cleve(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

It concludes by examining how these issues were debated during ratification, particularly the role played by moral ar-guments over slavery and the nature of the proposed union. Convention action on these slavery issues reflected the fundamentally different strate-gies the sections employed regarding them. The very limited northern public demand for control of slavery out-side the north meant that Northern delegates were free to make bargains on slavery designed to maximize northern economic development, while Southern delegates sought tenaciously to protect southern slave economies and their expansion potential. As to slave imports, Northern politicians agreed to accept a congressional power over such imports that imposed little constraint on the growth of slavery for a generation, allowing slave sales and imports to fuel westward expansion. On western settlement, a “side bargain” that included adoption of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also spurred slavery’s territorial expansion. At the same time, Congress’s formal powers over slavery in territories and new states were not explicitly limited. With respect to fugitives, the states ratified their existing policies against protecting them in the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause. The Constitution’s major policy protections for slavery and its expansion (in-cluding the western side bargain) were essential to its drafting and ratifi-cation. The Constitution and its side bargain reflected a shared elite under- c h a p t e r f o u r 144 standing that existing and projected regional political and economic de-velopment patterns should be accommodated in the national approach to development, and consequently to slavery. 1 The side bargain also rested on the premise that there would be no negative spillover from one region to another as a result of the other region’s development.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.