Social Sciences

Ethnicity and Religion Sociology

Ethnicity and religion in sociology refer to the study of how cultural and religious beliefs and practices intersect with social structures and identities. This field explores how ethnicity and religion shape individuals' experiences, social interactions, and group dynamics within societies. Sociologists examine the impact of ethnicity and religion on social inequality, conflict, and cooperation.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Ethnicity and Religion Sociology"

- James A Beckford, Jay Demerath, James A Beckford, Jay Demerath(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

Given the growing ethnic and religious diversity of the advanced industrial nations, it is not surprising that sociologists of religion have in recent years become increasingly interested in exploring once again the intersections of ethnicity and religion in an era of globalization. The consequence of the mass migration of people from the nations of the South and East to those of the North and West, the salience of this topic has stimulated a substantial expan-sion of research agendas by both sociologists of religion and immigration studies scholars. The relationship between these two modes of identity and communal affiliation is not a new topic in the field, and as a result, today’s researchers are able to build on a tradition of empirical inquiry and conceptual developments deriving from both the sociology of religion and from ethnic and immigration studies. This is particularly the case in the United States, where considerable attention in the past has been devoted to the religion of immigrants during the last great migratory wave, as well as to the religion of the black descendants of slaves. At the same time, given certain limita-tions to the lessons that can be learned from past efforts and due to some of the novel features of the present moment, we are indeed presented with, as Robert Wuthnow (2004) puts it, ‘the challenge of diversity.’ In this chapter, I will argue that there is a need to rearticulate the sociology of religion’s commonly employed ideal-typical formulation of the relationship between ethnicity and religion. In making this case, two recent developments are of particular relevance to that task, R. Stephen Warner’s (1993) ‘new paradigm’ for the study of religion and more broadly construed empirical and theoretical trends in immigration studies. In addition, the relevance of Rogers Brubaker’s (2004) idea of ‘ethnicity without groups’ for this task will be examined.- eBook - PDF

- Heather Griffiths, Nathan Keirns, Eric Strayer, Susan Cody-Rydzewski, Gail Scaramuzzo, Tommy Sadler, Sally Vyain, Jeff Bry, Faye Jones(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

In studying religion, sociologists distinguish between what they term the experience, beliefs, and rituals of a religion. Religious experience refers to the conviction or sensation that we are connected to “the divine.” This type of communion might be experienced when people are pray or meditate. Religious beliefs are specific ideas members of a particular faith hold to be true, such as that Jesus Christ was the son of God, or that reincarnation exists. Another illustration of religious beliefs is the creation stories we find in different religions. Religious rituals are behaviors or practices that are either required or expected of the members of a particular group, such as bar mitzvah or confession of sins (Barkan and Greenwood 2003). The History of Religion as a Sociological Concept In the wake of nineteenth century European industrialization and secularization, three social theorists attempted to examine the relationship between religion and society: Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Karl Marx. They are among the founding thinkers of modern sociology. As stated earlier, French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) defined religion as a “unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things” (1915). To him, sacred meant extraordinary—something that inspired wonder and that seemed connected to the concept of “the divine.” Durkheim argued that “religion happens” in society when there is a separation between the profane (ordinary life) and the sacred (1915). A rock, for example, isn’t sacred or profane as it exists. But if someone makes it into a headstone, or another person uses it for landscaping, it takes on different meanings—one sacred, one profane. Durkheim is generally considered the first sociologist who analyzed religion in terms of its societal impact. - eBook - PDF

- Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek, Bryan S Turner, Craig Calhoun, Chris Rojek, Bryan S Turner(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

INTRODUCTION: THE ORIGINS OF THE SOCIOLOGY OF RELIGION Religion refers to those processes and institu-tions that render the social world intelligible, and which bind individuals authoritatively into the social order. Religion is therefore a matter of central importance to sociology. To write sociologically is inevitably to work within a particular tradition that has in advance identi-fied certain issues and themes that are salient in the definition of social phenomena. The fact that a classical sociological tradition has already defined the field in advance appears to be particularly important in the case of religion (O’Toole, 2001; Robertson, 1970). In this over-view of the sociology of religion, I pay consid-erable attention to the legacies of Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, who defined the principal issues within the field, with respect to the analysis of the sacred and charisma. Within this tradition, I take the study of institutions to be our primary concern, partly as an analytical strategy to affirm that our topic of inquiry is not with individuals or persons. If we define sociology as the study of institutions, then reli-gious institutions have been a central preoccu-pation of sociologists. Indeed, the study of religious phenomena, including magic, ritual and myth, was an important feature of the intellectual origins of both anthropology and sociology. A number of social and cultural changes in the Victorian period created the intellectual context within which the sociologi-cal study of religion began to flourish in the late nineteenth century. In particular empirical evidence drawn from reports from Africa and Australia by colonial administrators, mission-aries and amateur anthropologists fired specu-lation about the origins of religion. The theory of animism suggested that ‘primitive mentality’ was a flawed attempt to understand Nature in the absence of experimental science. - eBook - PDF

- Bryan S Turner(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

CHAPTER 10 THE SOCIOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY OF RELIGION The study of religious phenomena, including magic and mythical systems, was an important general feature of the origins of contemporary social science. Indeed, speculation about religion represented a continuous theme in sociology and anthropology, running through the nineteenth century and into the classical period of the sociology of religion with writers like Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Herbert Spencer and Georg Simmel. With the nineteenth-century growth of European colonialism, there developed a consistent preoccupation with so-called primitive tribes, ‘lower races’, primitive cultures and finally with primitive mentality. Increasing evi-dence drawn from reports by colonial administrators, missionaries and amateur anthropologists fired speculation about the contrasting nature of advanced civilizations and primitive communities, where magical beliefs were seen to be exotic illustrations of the underlying primitive mentality of these colonized societies. Religion was seen to be analogous to the rela-tionship between childhood and adulthood in so far as primitive religions provided an insight into the historic origins of human communities as such. In addition, the strange customs of primitive peoples in far flung colonies provided, as it were, a living experience of Otherness for European observers. These nineteenth-century comparative inquiries laid much of the foundation for modern orientalism and lingering racist attitudes towards primitiveness. These studies were based on a powerful orientalist assumption about the uniqueness and superiority of the West in the evolu-tionary scale of human societies. However, out of this encounter with primitive cultures, a more mature and sophisticated sociology of belief systems began to emerge. - eBook - PDF

Making Sense of Collectivity

Ethnicity, Nationalism and Globalisation

- Sinisa Malesevic, Mark Haugaard(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Pluto Press(Publisher)

3 The Fundamentals of the Theory of Ethnicity 1 John Rex The study of ethnic relations has in recent years come to play a central role in the social sciences, to a large extent replacing class structure and class conflict as a central focus of attention. This has occurred on an interdisciplinary basis involving sociology, political theory, political philosophy, social anthropology and history. It has dealt with the theory of nationalism and the theory of transnational migrant communities and the problem of incorporating them into mod-ernising national societies. Each of these foci of study has developed its own separate theory but, what is worse, has sometimes claimed that it incorporates all the others. Thus, for example, the theory of nationalism has claimed to be a general theory of ethnicity, not recog-nising the difference between national groups and transnational systems of social relations and culture which bind together the members of migrating groups. Again, those who work within the discipline of social anthropology may feel that the field is exhaustively dealt with within its own problematic and limited range of interests. The object of this chapter is not simply to substitute a new general theory for these specialised theories but, while trying to do justice to their insights, to demonstrate the major points of theoretical connection between them by a careful process of conceptual analysis. I shall deal successively with the theoretical concepts involved as follows: the notion of primordiality and small-scale community; the notion of ‘ethnies’ and ethnic nationalism; the concept of the modern nation state and related forms of national-ism; the analysis of the structure of empires and colonial societies; that of the reconstitution of post-imperial societies; the concepts of economic and political migration and migrant ethnic mobilisation; what is involved in national policy responses to migration; and, finally, with the notion of multicultural societies. - eBook - PDF

- Bryan S. Turner, Bryan S. Turner, Bryan S. Turner, Bryan S. Turner(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

This is the Janus-faced inheritance of the sociology of religion. On one side, confi-dence that religion can be studied scientifically as an exciting social, cultural, and historical phenomenon. On the other side, the lurking suspicion that what we study is really something else disguised as religion and even if we are sure it is religion, that it really is not as relevant as we claim, or only has relevance in explaining deviations from modernity as apparent allegedly in the world-views of fundamentalists, those who are different from us moderns. This inheritance in large part accounts for the long preoccupation in the field with the puzzle of secularization and the (somewhat 410 MICHELE DILLON ironic) emergence in recent years of intellectual talk of the post-secular. In this chapter, I review the central theoretical strands that have shaped and comprise the sociology of religion, a narrative that inevitably begins with Weber and Durkheim. M AX W EBER ’ S S OCIOLOGY OF R ELIGION : D EFINITION AND M ETHODOLOGY Max Weber’s writings on religion demonstrated both the significance of different historical and cultural contexts on the evolution, development, and societal implica-tions of different religions as well as drawing attention to the intricate cultural intertwining of religion and societal structures. Although Weber never offered a formal definition of religion, it is clear from his writings that what he saw as socio-logically significant was the substantive content of beliefs: how do particular beliefs about salvation orient social actors to the world and motivate social action? Dif-ferent world religions produce different world-orientations with different practical consequences for the sorts of institutions and authority structures that emerge. - eBook - PDF

- Kiri Paramore(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

2 Religion in the Sociology and Anthropology of India Rowena Robinson Introduction The question posed in this volume with regard to the role played by religion in the constitution and practice of Area Studies and allied fields is enormously relevant in the context of understanding the historical development of the disciplines of sociology and social anthropology in India. In India, the study of religion was the precursor to sociology and anthropology and these disciplines were in turn largely the study of religion and, by extension, of caste. To a considerable extent, the present Studies of religion within these disciplines speak of a vigorous and thoroughgoing attempt to disengage from received understandings and disentangle threads of interpretation that have their origin in Indological characterizations of Indic religions. In this chapter, I will argue that anthropology and sociology in India have been infused by regionalism. India has been treated as a cultural and civilizational region defined by Hinduism; other religions are seen unambiguously as coming from outside. Religions that emerged within India have been typically fused with Hinduism. The roots of anthropology and sociology lay in Indological and Orientalist knowledge of the early decades of the twentieth century. It must be said that the concept of Area Studies can hardly resonate for a scholar located in India or South Asia. On the other hand, one might argue that Orientalism while promoting Area Studies actually prevented regional studies from developing thoroughly and restricted regionalism instead to ‘India-centrism’ (versus the West). Thus, if the Area Studies model is to be replaced by one less tainted because of its origins and Religion and Orientalism in Asian Studies 26 more attuned to contemporary academic concerns, it might be something along the lines of comparative South Asian Studies – the ‘region’ is not set aside but is rather brought more fully into focus and made to do more work. - eBook - PDF

Theology and Religious Studies in Higher Education

Global Perspectives

- D.L. Bird, Simon G. Smith(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

Chapter 7 Towards a Socio-cultural, Non-theological Definition of Religion James L. Cox Introduction This chapter contends that the academic study of religions is undertaken not to achieve any number of worthy or noble ends, such as fostering world peace, encouraging inter-religious dialogue, elevating dispossessed peoples to positions of power or to substantiate philosophical or theo-logical arguments. Rather, its aim is to provide a framework for identifying those human activities which can be called ‘religion’, and to make asser-tions about such activities that can be tested empirically. For this reason, a proper understanding of the relationship between the academic study of religions and theology depends on the way religion is defined. In this chapter, the author proposes a two-pronged definition. One part focuses on the beliefs and experiences which identifiable communities postulate about non-falsifiable alternate realities and the other, following the French sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger, examines religion as the authoritative transmission of tradition. The chapter concludes that by defining religion in these ways, notions of theological essentialism are uprooted from their longstanding association with the study of religions, thereby firmly situat-ing religious studies among the social sciences. I have chosen to present a religious studies perspective on the topic by proposing what I am calling a socio-cultural, non-essentialist definition of religion. I regard a definition as an appropriate starting place, because, in my view, much confusion has been generated by the so-called ‘object’ of the study of religions, which in turn has led to further confusion about methods appropriate to religious studies. By clarifying the meaning of reli-gion, I hope to decouple the category from its longstanding association with theology. - eBook - PDF

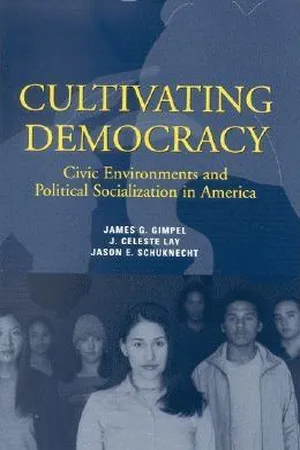

Cultivating Democracy

Civic Environments and Political Socialization in America

- James G. Gimpel, J. Celeste Lay, Jason E. Schuknecht(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Brookings Institution Press(Publisher)

However, the context that matters is reli-gious context, not racial or ethnic context. To be sure, race and ethnicity matters, but church congregations are so highly segregated by race that it is not the race or ethnic composition of the community that matters nearly so much as the race and ethnicity of the individual adherents. Religion 139 Table 5-4. Influence of Racial or Ethnic Context and Local Religious Concentration on Discussion, Knowledge, and Efficacy, Controlling for Family Socioeconomic Status and Individual Race or Ethnicity* Units as indicated Fixed effects School means (Po) Jewish re-spondent (Pj) Protestant re-spondent O 2 ) Catholic re-spondent (p 3 ) Regular at-tendance (P 4 ) Black re-spondent O 5 ) Asian re-spondent (3 6 ) Hispanic re-spondent (P 7 ) Socioeconomic status ((B 8 ) Summary statistic Explanatory variable Intercept Percent black Percent Hispanic Intercept Percent Jewish Intercept Percent Protestant Percent black Intercept Percent Catholic Percent Hispanic Intercept Intercept Intercept Intercept Intercept Level-one respondents (TV) Percent reduction in error Frequency of political discussion 21.79** (2.21) -0.08 (0.06) 0.07 (0.11) 6.72** (2.49) -0.41** (0.09) -4.76** (1.55) 0.04 (0.03) 0.07 (0.05) -0.61 (2.14) -0.12* (0.08) -0.12 (0.08) 0.65** (0.31) -4.06** (1.19) -1.98 (2.14) -1.74 (2.27) 0.23** (0.07) 2,120 3.2 Level of political knowle dge 65.48** (1.82) -0.06* (0.03) -0.07 (0.12) 1.04 (2.72) -0.06 (0.11) 2.79* (1.46) -0.10** (0.05) 0.02 (0.02) 0.33 (1.79) -0.02 (0.05) -0.06 (0.05) -0.02 (0.27) -6.72** (1.25) -2.44* (1.43) -4.77** (1.79) 0.35** (0.06) 2,098 5.1 Internal political efficac y 47.44** (0.81) -0.04** (0.01) 0.08 (0.07) 5.60** (1.62) -0.25** (0.08) 2.23 (1.79) -0.03 (0.06) -0.02 (0.01) 2.10 (1.31) -0.10** (0.06) -0.05 (0.05) -0.12 (0.20) -2.70** (0.63) -0.97 (1.12) -2.43 (1.53) 0.16** (0.04) 2,119 3.2 External political e fficacy 41.81** (0.64) -0.04** (0.02) -0.08 (0.06) 2.09 (1.87) -0.02 (0.07) 0.90 (1.38) -0.03 (0.05) 0.02 (0.02) 2.21** (0.88) -0.12** (0.04) 0.07 (0.04) -0.14 (0.26) -1.80** (0.67) 2.20* (1.14) 0.12 (0.81) 0.04 (0.02) 2,115 2.1 Source: Metro Civic Values Survey, 1999-2000. - eBook - ePub

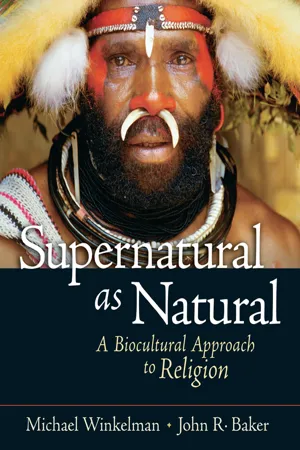

Supernatural as Natural

A Biocultural Approach to Religion

- Michael Winkelman, John R. Baker(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The structural–functional approach of Evans-Pritchard does not fully embrace Durkheim’s view that religion is defined by the sacred, nor does it completely reject the intellectualist view that religion is a belief in supernatural beings. His work shows how religious beliefs are related to the structures of society. He argues that this is the influence of social structure on religion, rather than a social determination of the beliefs and ideas regarding spirits.Religion as a Cultural System

In his classic article “Religion as a Cultural System,” Clifford Geertz (1966) integrates the intellectualist concern over the explanatory role of religion with the functionalist perspective. In doing so, Geertz provides a broad and all-encompassing definition of religion that incorporated the intellectual, emotional, symbolic, and social aspects of religion as part of the total world-view of a culture. Geertz’s definition, which has resonated with many anthropologists, sees religion as “(1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, persuasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of actuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (Geertz 1966).A key aspect of Geertz’s conception of religion is its role as a symbol system—a system of interconnected meanings that function to express the essence of a culture’s worldview and ethos, encompassing such diverse domains as morals, character, values, aesthetics, and cosmology. The principal function of religion is to illustrate the conformance between everyday life and the ideal view of the Universe that is depicted in a culture’s cosmology. Religious rituals provide mechanisms to make this connection emotionally convincing, giving people a certainty that the general principles in which they believe actually operate in the Universe. Religion projects a cosmic order that serves as a general model of the Universe, and then socializes human beings to help to ensure that people’s morals, emotions, and judgments conform to these ideals.Symbol System

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.