Technology & Engineering

Thermal Conductivity of Metals

Thermal conductivity of metals refers to their ability to conduct heat. It is a measure of how efficiently a metal can transfer heat through its structure. Metals with high thermal conductivity are often used in applications where heat transfer is important, such as in heat exchangers and electronic devices.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Thermal Conductivity of Metals"

- eBook - ePub

Electronic Materials

Principles and Applied Science

- Yuriy Poplavko(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Elsevier(Publisher)

It is necessary to mention that there are many metals with small resistance at nitrogen temperature. However, a significant advantage at liquid nitrogen temperature is beryllium: exactly it has the smallest possible ρ value. In contrast to superconductivity, hyperconductivity is not destroyed by magnetic field. At that, hyperconductive metals must be well cleaned to have perfect structure [5]. 5.3 Thermal Properties of Metals According to classic electronic theory of metals, a solid conductor may be represented as a system, consisting of ionic lattice that contains inside “gas” of collectivized (free) electrons. Assuming the metal as a crystal, in which positive ions form stable lattice with mobile electrons between them can explain many basic properties of metals: ductility, malleability, high thermal conductivity, and large electrical conductivity. Similar to a solid state, in a liquid state of metal a large number of free electrons exist: n e = (0.5–25) × 10 − 22 cm − 3 ; they are the charge carriers providing electrical current passage through a metal. At normal temperature, electron mobility in metals is u = (2–7) × 10 − 5 m 2 /(V s). Thermal Conductivity of Metals. Heat transmission through a metal occurs by the same free electrons that determine electrical conductivity. Thermal Conductivity of Metals is high due to a large number of electrons per unit volume of metal. At the same time, the coefficient of thermal conductivity by electrons λ e in metals exceeds thermal conductivity λ ph in dielectrics, where heat transferred mainly has phonon nature. Obviously, if other things being equal, the higher the specific electrical conductivity σ in a metal the greater the metal thermal conductivity λ e. As temperature increases, the mobility of electrons in metal and, therefore, its electrical conductivity σ reduces; at that, ratio λ e / σ has to grow - Allan D. Kraus, James R. Welty, Abdul Aziz(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

In the solid phase, thermal conductivity is attributed to both molecular interaction and free-electron drift that is present, primarily, in pure metals. The solid phase is amenable to quite precise measurements of thermal conductivity because there is no effect of convection currents. The thermal properties of most solids of engineering interest have been evaluated. Table A.17 (for metals) and Table A.18 (for nonmetallic solids) listing thermal conductivities and other properties are included in Appendix A. The thermal conductivity of a liquid is not amenable to any simplified kinetic-theory development because the molecular behavior of the liquid phase is not clearly understood and no universally accurate mathematical model presently exists. Some empirical correla-tions have met with reasonable success, but they are so specialized they will not be included in this book. A general observation about liquid thermal conductivities is that they vary only slightly with temperature and are relatively independent of pressure. One problem in experimentally determining values of the thermal conductivity in a liquid is making sure that the liquid is free of convection currents. Table A.14 gives the thermal conductivity of water as well as other properties and Table A.16 provides similar properties for several other liquids. The kinetic theory of gases can be used to predict the thermal conductivity of gases and experiments confirm that the thermal conductivity is proportional to the absolute temperature, Table A.13 gives the thermal conductivity of air as well as other properties and Table A.15 provides similar properties for several other gases. Figure 19.1 illustrates the thermal conductivity variation with temperature of several important materials in solid, liquid, and gas phases.- Aamir Shahzad(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

Section 2 Thermal Conductivity of Solid and Fluid Systems Chapter 5 Thermal Conductivity of Liquid Metals Peter Pichler and Gernot Pottlacher Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.75431 Abstract Over the last decades, many experimental methods have been developed and improved to measure thermophysical properties of matter. This chapter gives an overview over the most common techniques to obtain thermal conductivity λ as a function of temperature T . These methods can be divided into steady state and transient methods. At the Institute of Experimental Physics at Graz University of Technology, an ohmic pulse-heating appa-ratus was installed in the 1980s, and has been further improved over the years, which allows the investigation of thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity for the end of the solid phase and especially for the liquid phase of metals and alloys. This apparatus will be described in more detail. To determine thermal conductivity and thermal dif-fusivity with the ohmic pulse-heating method, the Wiedemann-Franz law is used. There are electronic as well as lattice contributions to thermal conductivity. As the materials examined at Graz University of Technology, are mostly in the liquid phase, the lattice contribution to thermal conductivity is negligibly small in most cases. Uncertainties for thermal conductivity for aluminum have been estimated ±6% in the solid phase and ±5% in the liquid phase. Keywords: thermal conductivity, ohmic pulse-heating, Wiedemann-Franz law, sub-second physics, high temperature, liquid phase 1. Introduction Knowing thermophysical properties, i.e., properties that are influenced by temperature, of metals and alloys is not only of academic interest, but also profoundly important for industry and commerce. Casting of metal objects, made of, e.g., steel or aluminum, is prone to cast-ing defects and imperfections.- eBook - ePub

Mechanical Engineers' Handbook, Volume 1

Materials and Engineering Mechanics

- Myer Kutz(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Temperature control is directed at maintaining electronic component temperatures within prescribed limits. This is accomplished by the proper selection and application of materials which are used to conduct heat from or to the components.The primary modes of heat transfer are conduction, convection, and radiation. The dominant considerations for heat transfer material selection include thermal conductivity, chemical inertness, resistance to corrosion, and sometimes wear resistance, sublimation, thermal expansion, and the ability to resist ionizing and ultraviolet radiation.Conduction heat transfer involves the flow of thermal energy through a material from a heat source (component) to a heat sink. The design goal is to reduce the resistance to heat flow between the heat source and the heat sink. The effectiveness of heat transfer within a material is measured by its thermal conductivity. Metals such as silver, copper, and aluminum are good heat conductors; however, aluminum is most often used because it tends not to tarnish, is easy to form, and costs less. Copper or copper alloys are used when large amounts of heat are to be transferred and any small improvement in thermal conductivity is meaningful in the design.When the design requires electrical insulation and good thermal conduction across a joint between two materials, thin layers of mica, silicon-impregnated cloth, and ceramic materials are often used. The thermal conductivity of these joints may be enhanced by applying a thermal grease to the joining parts to prevent the entrapment of air or other gas (a thermal insulator) between the mating surfaces.Convection heat transfer involves the movement of heat between one material (usually metal) to a surrounding material such as a gas (air) or a liquid (water, Freon, etc.). A convection design seeks to conduct heat from a heat source into a physical configuration, such as fins, which presents a relatively large area of contact between the metal object and the gas or liquid with which the heat is to be exchanged. Good thermal conductivity is very important; so is strength and resistance to corrosion. Convection heat sinks are often made from high-strength aluminum alloys to meet these requirements. For resistance to corrosion, which may result in the formation of a thermally insulating film between the heat transfer media, the aluminum heat sink is sulfuric acid anodized black in color to also enhance heat transfer by radiation. - eBook - PDF

Fundamentals of Materials Science and Engineering

An Integrated Approach

- William D. Callister, Jr., David G. Rethwisch(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

764 • Chapter 17 / Thermal Properties contribution results from a net movement of phonons from high- to low-temperature regions of a body across which a temperature gradient exists. Free or conducting electrons participate in electronic thermal conduction. A gain in kinetic energy is imparted to the free electrons in a hot region of the specimen. They then migrate to colder areas, where some of this kinetic energy is transferred to the atoms (as vibrational energy) as a consequence of collisions with phonons or other imperfections in the crystal. The relative contribution of k e to the total thermal conduc- tivity increases with increasing free electron concentration because more electrons are available to participate in this heat transference process. Metals In high-purity metals, the electron mechanism of heat transport is much more efficient than the phonon contribution because electrons are not as easily scattered as phonons and have higher velocities. Furthermore, metals are extremely good conductors of heat because relatively large numbers of free electrons exist that participate in thermal con- duction. The thermal conductivities of several common metals are given in Table 17.1; values generally range between about 20 and 400 W/m ∙ K. Because free electrons are responsible for both electrical and thermal conduction in pure metals, theoretical treatments suggest that the two conductivities should be related according to the Wiedemann–Franz law: L = k σT (17.7) where is the electrical conductivity, T is the absolute temperature, and L is a constant. The theoretical value of L, 2.44 × 10 –8 Ω ∙ W/(K) 2 , should be independent of temperature and the same for all metals if the heat energy is transported entirely by free electrons. Table 17.1 includes the experimental L values for several metals; note that the agreement between these and the theoretical value is quite reasonable (well within a factor of 2). - eBook - PDF

Applied Materials Science

Applications of Engineering Materials in Structural, Electronics, Thermal, and Other Industries

- Deborah D. L. Chung(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

24 References ................................................................................................................ 25 SYNOPSIS Materials for thermal conduction are reviewed. They include materials exhibiting high thermal conductivity (such as metals, carbons, ceramics, and com-posites), and thermal interface materials (such as polymer-based and silicate-based pastes and solder). 2.1 INTRODUCTION The transfer of heat by conduction is involved in the use of a heat sink to dissipate heat from an electronic package, the heating of an object on a hot plate, the operation of a heat exchanger, the melting of ice on an airport runway by resistance heating, the heating of a cooking pan on an electric range, and in numerous industrial processes that involve heating or cooling. Effective transfer of heat by conduction requires materials of high thermal conductivity. In addition, it requires a good thermal contact between the two surfaces in which heat transfer occurs. Without good thermal contacts, the use of expensive thermal conducting materials for the components is a waste. The attainment of a good thermal contact requires a thermal interface material, 2 16 Applied Materials Science such as a thermal grease, which must be thin between the mating surfaces, must conform to the topography of the mating surfaces, and should preferably have a high thermal conductivity. This chapter is a review of materials for thermal conduction, including materials of high thermal conductivity and thermal interface materials. 2.2 MATERIALS OF HIGH THERMAL CONDUCTIVITY 2.2.1 M ETALS , D IAMOND , AND C ERAMICS Table 2.1 provides the thermal conductivity of various metals. Copper is most commonly used when materials of high thermal conductivity are required. However, copper suffers from a high value of the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE). A low CTE is needed when the adjoining component has a low CTE. - eBook - PDF

- Iris Nandhakumar, Neil M White, Stephen Beeby(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Royal Society of Chemistry(Publisher)

Measuring the effective thermal resistance also enables a more accurate comparison of materials within the same lab. Ensuring that all the specimens are of the same size and shape, the errors associated with thermal interface resistance and uncertainty in determination of the specimen dimensions 6 are eliminated. However, in order to link this property with theoretical research, it is desirable to obtain the intrinsic property of the material, the thermal conductivity. Thermal conductivity, k , is the property of a material that quantifies its ability to transport heat when subject to a temperature gradient. It can be determined according to the commonly used Fourier heat conduction equation by measuring a temperature gradient across a specimen in response to a known heat flux passing through it: _ Q A ¼ k D T D l (5 : 1) 110 Chapter 5 Where Q _ is the heat flux [W] passing through the specimen, A and D l are the specimen cross-section [m 2 ] and length [m], respectively, and D T is the temperature gradient [K]. The Fourier equation in this form implies that the thermal conductivity is constant along the direction of heat flux. However, thermal conductivity often being a function of temperature, may vary significantly along this direction. Generally, a measured value for thermal conductivity is assumed to relate to the mean specimen temperature. However, this assumption can only be used if the thermal conductivity has a linear temperature depend-ence or when a sufficiently small temperature gradient is applied in order to approximate a linear temperature dependence. It is important to understand that there is no universal method for determining the thermal conductivity covering the whole range of temperatures and thermal conductivities (five orders of magnitude), as each method has its own specific problems and limitations. There are various technical issues that can be encountered depending on the thermal con-ductivity range of the material of interest. - Frank P. Incropera, David P. DeWitt, Theodore L. Bergman, Adrienne S. Lavine(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

As illustrated in Figure 2.4, the thermal conductivity of a solid may be more than four orders of magnitude larger than that of a gas. This trend is due largely to differences in intermo- lecular spacing for the two states. The Solid State In the modern view of materials, a solid may be comprised of free elec- trons and atoms bound in a periodic arrangement called the lattice. Accordingly, transport of thermal energy may be due to two effects: the migration of free electrons and lattice vibra- tional waves. When viewed as a particle-like phenomenon, the lattice vibration quanta are termed phonons. In pure metals, the electron contribution to conduction heat transfer domi- nates, whereas in nonconductors and semiconductors, the phonon contribution is dominant. Kinetic theory yields the following expression for the thermal conductivity [1]: k Cc 1 3 mfp λ = (2.7) For conducting materials such as metals, C ≡ C e is the electron specific heat per unit vol- ume, c is the mean electron velocity, and λ mfp ≡ λ e is the electron mean free path, which is defined as the average distance traveled by an electron before it collides with either an imperfection in the material or with a phonon. In nonconducting solids, C ≡ C ph is the pho- non specific heat, c is the average speed of sound, and λ mfp ≡ λ ph is the phonon mean free 0.1 0.01 1 10 100 1000 Thermal conductivity (W/m • K) GASES INSULATION SYSTEMS LIQUIDS NONMETALLIC SOLIDS ALLOYS PURE METALS Silver Zinc Nickel Aluminum Oxides Ice Plastics Fibers Foams Oils Water Mercury Hydrogen Carbon dioxide FIGURE 2.4 Range of thermal conductivity for various states of matter at normal temperatures and pressure. 64 Chapter 2 ■ Introduction to Conduction path, which again is determined by collisions with imperfections or other phonons. In all cases, the thermal conductivity increases as the mean free path of the energy carriers (elec- trons or phonons) is increased.- eBook - PDF

Handbook of Polymer Testing

Physical Methods

- Roger Brown(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

1 Introduction 24 Thermal Properties David Hands Consultant, Sutton Farm, Shrewsbury, England This chapter deals with the measurement of thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat. Other properties that are sometimes included under the umbrella term thermal properties are dealt with in other parts of this volume. In most cases it does not matter whether the sample is a rubber or a plastic, the experimental techniques are the same. 2 General Theory 2.1 Equation of Conduction of Heat For the flow of heat in one direction, the heat flux luis related to the temperature gradient ae;ax by Fourier's law ae lu = -K-(1) ax where K is the thermal conductivity. The minus sign indicates that the heat flows in the opposite direction to the temperature gradient. The form of Eq. I implies that heat con-duction is a random process. If energy were propagated without scattering, then the heat flow would depend on the temperature difference between the end faces of the specimen instead of the temperature gradient [1]. The general equation from which the time-dependent temperature distribution may be calculated is obtained from Eq. I and the equation of continuity aJu ae -= -pc-ax at (2) 597 598 Hands where pis the density, cis the specific heat, i.e., the heat capacity per unit mass, and tis the time. The equation of continuity is an expression of the conservation of energy. The heat flux can be eliminated between Eqs. I and 2 to give a 2 e 1 aK (ae) 2 1 ae ax 2 + J( ae ax = ~ at (3) where a= K/ pc is the thermal diffusivity. Eq. 3 is the equation of conduction of heat, in the absence of heat generation and convection, for heat flow in one direction. If the conductivity is independent of temperature it reduces to a 2 e 1 ae ax 2 -~at (4) which is the equation usually referred to. It has been shown that for rubbers, and for plastics except at melting transitions, the conductivity term in Eq. 3 is very small, and Eq. 4 is adequate for most heat flow calculations [2] . - eBook - PDF

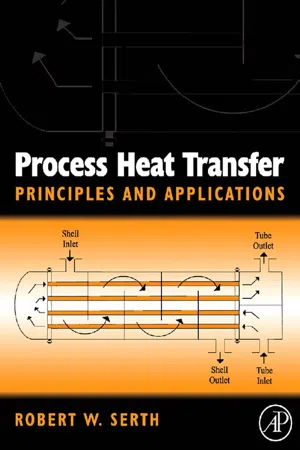

Process Heat Transfer

Principles, Applications and Rules of Thumb

- Thomas Lestina, Robert W. Serth(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

The theory was based on the results of experiments similar to that illustrated in Figure 1.1 in which one side of a rectangular solid is held at temperature T 1 , while the opposite side is held at a lower temperature, T 2 . The other four sides are insulated so that heat can flow only in the x -direction. For a given material, it is found that the rate, q x , at which heat (thermal energy) is transferred from the hot side to the cold side is proportional to the cross-sectional area, A , across which the heat flows; the temperature difference, T 1 − T 2 ; and inversely proportional to the thickness, B , of the material. That is: q x ∝ A ( T 1 − T 2 ) B Writing this relationship as an equality, we have: q x = k A ( T 1 − T 2 ) B (1.1) T 2 q x x Insulated Insulated Insulated B q x T 1 Figure 1.1 One-dimensional heat conduction in a solid. HEAT CONDUCTION 1/3 The constant of proportionality, k , is called the thermal conductivity. Equation (1.1) is also applicable to heat conduction in liquids and gases. However, when temperature differences exist in fluids, con-vection currents tend to be set up, so that heat is generally not transferred solely by the mechanism of conduction. The thermal conductivity is a property of the material and, as such, it is not really a constant, but rather it depends on the thermodynamic state of the material, i.e., on the temperature and pressure of the material. However, for solids, liquids, and low-pressure gases, the pressure dependence is usually negligible. The temperature dependence also tends to be fairly weak, so that it is often acceptable to treat k as a constant, particularly if the temperature difference is moderate. When the temperature dependence must be taken into account, a linear function is often adequate, particularly for solids. In this case, k = a + bT (1.2) where a and b are constants. Thermal conductivities of a number of materials are given in Appendices 1.A–1.E. - eBook - ePub

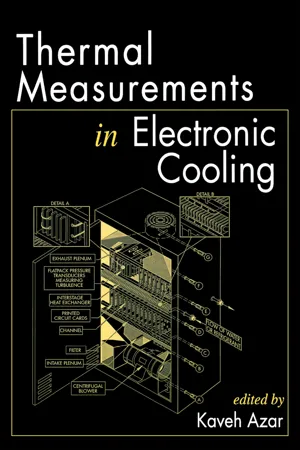

- Kaveh Azar(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Thermal radiation is the electromagnetic radiation given off by any material whose temperature is above absolute zero. It covers a wide spectrum of wavelengths (~0.1 to 100 μm) and is governed by a basic physical law with only one material-dependent factor, ε, the emissivity. Crudely speaking, ε for metals depends inversely on how “shiny” the material is, particularly in the infrared part of the spectrum. For many materials, the emissivity depends directly on how “black” the surface appears. Depending on the material, e can range over several orders of magnitude, from a maximum of 1.0 for an ideal black body to low values of −0.02 for some highly polished metals.Thermal loss to a surrounding fluid is more complicated physically because it includes several mechanisms: (1) simple thermal conduction through a stable fluid, (2) extra conduction due to rolls and other gravitational instabilities (natural convection) which provide cooler fluid flowing past an object, and (3) forced convection of fluid past the object with the use of fluid movers (e.g., fans), resulting in either laminar or turbulent flow. These three mechanisms are usually lumped together approximately (Carslaw and Jaeger, 1959) by writing down a heat flux that depends on some low power of ΔT, the temperature difference between the hot object and the surroundings, with a proportionality constant determined empirically7.1.3 Example: Measuring thermal conductivity of multilayer boards

To illustrate how some of these quantities can be obtained, we describe measurements (Azar and Graebner, 1996) of a sample of printed wiring board (PWB). The specimen (1 cm × 5 cm × 0.1 cm) is cut from a standard 6-layer, 0.1 cm thick PWB which has a number of layers of Cu foil sandwiched between layers of fiberglass-epoxy. An electrical resistance heater wire is attached with epoxy as a thermal transfer agent at one end and the sample is thermally grounded to a copper block by clamping at the other end. The heat is applied uniformly across one end and the thermal grounding is done as uniformly as possible across the other end (see below) so that the heat flow at all points is uniformly parallel to the long direction of the sample. This restriction to low-dimensional heat flow (in this case, one-dimensional) simplifies the analysis enormously and is a profitable approach in many thermal measurement problems.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.