1

The Laboratory in the Salon

Spiritualism Comes to Russia

The origins of the widespread late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century fascination with the transcendental in the Russian empire go back about half a century to the 1850s, when spiritualism made its first appearance in Russia.1 Initially, spiritualists constituted a small and exclusive group of highly educated and socially privileged people. By the end of the century, their constituency had widened significantly, and this development changed the character of spiritualist practice and thought. The history of spiritualism in Russia from its inception to the early stages of its popular success, and the importance of scientific thought and aristocratic forms of sociability to its development, lies at the center of this chapter.

Spiritualism came to Russia from the United States via Western Europe.2 The beginnings of modern spiritualism can be dated quite precisely to March 31, 1848, when two teenage girls, Kate and Margaret Fox, heard knocks in their house in Hydesville, in upstate New York, which they claimed came from the other world. They soon established communications with the alleged spirit, and newspapers quickly spread the news about their success to other parts of the United States.3 Numerous contemporaries emulated their example and began to communicate with the dead, and the ritual of the spiritualist séance emerged. These were gatherings at which participants assembled in darkened rooms and, aided by the nervous sensitivity of a medium, awaited supernatural occurrences. Even the periodic discovery of deception did not halt the spread of these activities.4 American spiritualism soon spread to Europe, and Britain eventually became home to one influential strain of spiritualism in the Old World. British mediums developed famous reputations, the island’s spiritualists were famed for their scientific study of séance phenomena, and many continental Europeans, including Russians, were proud to be accepted into the membership of celebrated British associations devoted to the topic.5 A second, more mystical strand of spiritualism developed in France under the leadership of Allan Kardec, whose ideas elaborated theories about reincarnation in addition to spirit communication.6 Both the British and the French style of spiritualism found supporters in Russia.

In Russia, spiritualism became a topic of salon conversations in the 1850s. The lawyer Anatolii Fedorovich Koni recalled in his memoirs how, along with the game of lotto, “the gullible pursuit of prophetic tables” became “a popular pastime” at this time. “Many passionately took up these things, putting a miniature purpose-built table with a little hole for a pencil on a sheet of paper and placing on it the hands of those through whom the spirits liked to communicate in writing ‘the secrets of eternity and the grave.’”7

Later, Russian adepts precisely dated the emergence of spiritualism in Russia to the winter season of 1852. “Tables, hats, and saucers turned everywhere and talks about rappings at night began to make their rounds.”8 Russian spiritualism received a boost in 1858, when Daniel Dunglas Home (pronounced “Hume”) visited the empire.9 Home was arguably the most famous medium of all time. He was born in Scotland but grew up in New England, where he discovered his mediumistic abilities. He never had another profession apart from his spiritualist career, and he was the only medium never to have been exposed as a fraud. In 1858, Home travelled to Rome where he met his future wife, the seventeen-year-old Aleksandra Kroll, a goddaughter of the tsar. In the same year, on the occasion of his marriage to Aleksandra, Home visited his wife’s homeland for the first time, and the couple stayed in Russia for almost a year. Home held numerous séances, which were attended by exquisite and select members of the high aristocracy, including Alexander II himself. Yet, despite the extended time Home spent in Russia, his visit did not have major consequences for the spread of spiritualism in the tsarist empire. His audience, it seems, was too exclusive to turn séances into truly popular pursuits.

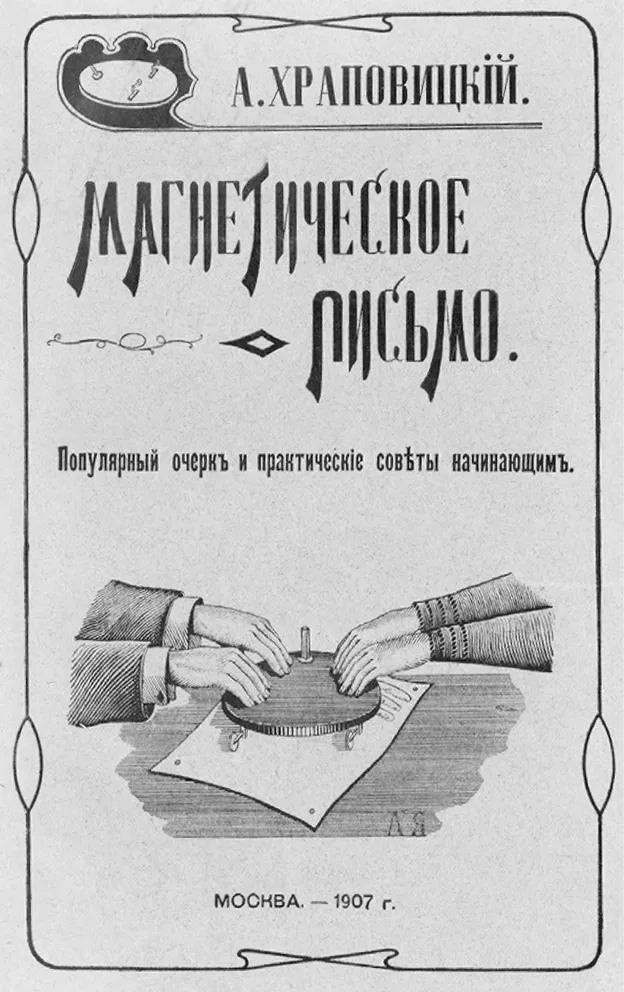

Figure 1: Depiction of a planchette, a device used during séances to record messages from the beyond. Khrapovitskii, A. Magneticheskoe pis’mo. Moscow, 1907.

Spiritualists later bemoaned that séances “were not treated with the necessary seriousness” in the 1850s and “served almost exclusively as fashionable and marvelous salon entertainment.”10 Indeed, the infatuation with spiritualism in the 1850s did not leave a lasting trace and produced few manuscripts or published documents. Spirit messages from beyond the grave were as ephemeral as their alleged authors; the fashion appeared briefly and at intervals, before disappearing almost immediately.11 Articles in Russian ecclesiastical journals published in the 1860s support this assessment by describing spiritualist séances purely as Western idiosyncrasies.12 According to V. Snegirev, writing in 1871, only a few Russian aristocrats had thus far become acquainted with spiritualism on their “travels through Western Europe and, for want of anything better to do, had brought all sorts of marvels home.”13 Snegirev might well have been hinting at Home’s visits and his friendship with Russian aristocrats, since the medium was invited to visit the empire again in 1865, when he gave further sittings for the emperor. Snegirev concluded his musings with the expectation that “without any doubt, [spiritualism] will, in one way or another, sooner or later, spread to the masses.”14 Within a few years, his prediction was to become true.

In February 1871, Home accepted a further invitation to come to Russia. In St. Petersburg, his séances were attended by a number of Russian scholars, among them Aleksandr Nikolaevich Aksakov and the chemist Aleksandr Mikhailovich Butlerov. Home was also introduced to Butlerov’s sister-in-law, Iuliia Glumelina, and almost immediately became engaged to her (Aleksandra had died of consumption in 1862). This union strengthened the link between the famous medium, the empire’s intelligentsia, and Russian society more generally. Eventually, Home’s reputation in Russia grew so legendary that it became impossible to regard him as anything other than “the Russian medium Home,” or “russkii medium Ium.”15

Home, and the spiritualist phenomena he elicited, found enthusiastic supporters in Aksakov and Butlerov. Aksakov was to become Russia’s most active, vigorous, and famous spiritualist.16 Aleksandr Nikolaevich was a member of the prominent Aksakov family, a nephew of the writer Sergei Timofeevich Aksakov, and a cousin of the Slavophiles Ivan and Konstantin. He had been educated at the imperial lycée, where at a young age he had developed an interest in philosophy and religion and had studied, among others, Swedenborg’s writings.17 In 1852, Aksakov took part in Andrei Mel’nikov-Pecherskii’s expedition to Old Believer communities in Nizhnii Novgorod guberniya before joining the state service in 1868.

Aksakov later wrote that he had been interested in questions relating to spiritualism since 1855, but his first personal experience of séances did not occur before 1870.18 After this experience, he immediately became convinced of the authenticity of spiritualist phenomena and spent the remainder of his life and funds publicizing spiritualist tenets. In response to Home’s 1871 visit to St. Petersburg, Aksakov published a brochure, Spiritualizm i nauka (Spiritualism and Science), in which he discussed the medium’s feats.19 The title is significant, for Aksakov saw himself as the champion of a new science that would investigate the world beyond the grave and eventually revolutionize scientific and religious knowledge.20 Unlike his friend Butlerov, however, Aksakov had not had any formal scientific education or training. For two years, the young Aksakov had attended lectures in anatomy, physiology, chemistry, and physics as a private student at Moscow University, but he failed to obtain a university degree in any of those subjects (indeed, in any subject at all), a fact upon which his pompous autobiographical sketches of the 1890s remain uncharacteristically quiet.21 Nevertheless, Aksakov described his informal Moscow education as vital, for it provided him with the necessary knowledge so as “not to be impressed by scientists” when they disagreed with his spiritualist convictions.22

Aksakov’s activities to promote spiritualism mimicked academic conventions. During séances, Aleksandr Nikolaevich wrote detailed minutes, which he archived and could retrieve years later.23 He also occasionally employed exact instruments, such as thermometers and barometers, to register the influence of the weather on séance phenomena.24 In the 1890s, and possibly also earlier, Aksakov copied the practice of university professors and hired a graduate student as his research assistant.25 His academic aspirations were mirrored, moreover, in his publishing enterprises. In 1874, Aksakov founded and privately financed the Leipzig journal Psychische Studien; like academic periodicals, it was published in regular installments and offered reports of recent supernatural occurrences, accounts of séance experiments, and theoretical discussions about the topic. Aksakov also immediately brought out a German translation of his Spiritualizm i nauka. Like the journal, his magnum opus, Animismus und Spiritismus, was also initially published in Leipzig before appearing in Russian, French, and Italian.26 Aksakov himself claimed that the aim of these German publications was to “bring spiritualism to the attention of [Germany’s] scholars” and thereby to contribute to its rational investigation and eventual acceptance by the scientific community.27 The choice of location and language is significant. By concentrating his efforts on the nation with the most eminent scientific reputation in tsarist Russia and by publishing in the lingua franca of nineteenth-century learning, Aksakov underscored his academic aspirations. Moreover, the internationalism of his activities, including his publications, his correspondence with like-minded western European contemporaries, and his travels abroad, replicated the cosmopolitanism of the scholarly community.28

Aksakov did not neglect Russia and vigorously propagated spiritualism there too, mercilessly sending his writings to prominent acquaintances, including public cultural figures such as the historian, lawyer, and sociologist Konstantin Dmitrievich Kavelin, the writer Nikola...