![]()

1Introduction and overview

Owing to the discussions that have been ongoing for some time now both nationally and internationally with regard to the complete or partial abolition of cash, the placing of restrictions on cash payments or the more general attempts to make cash payments unattractive, the advantages and disadvantages of cash have generated substantial public interest. Therefore, modules 2 and 3 of the study on the “Costs and benefits of cash and cashless payment instruments”, commissioned by the Deutsche Bundesbank, will focus on the costs and benefits of cash. This part, module 2, will focus on the benefits.1 These benefits will be analysed at both the microeconomic and the macroeconomic level, as well as in terms of societal aspects.2 The line of reasoning is primarily of a qualitative nature. In general, no attempts will be made to quantify the identified benefits.

Given that cash is still used intensively, one could, in principle, simplify matters by arguing that the revealed preferences of the general public clearly show that cash is deemed to be useful, otherwise nobody would use it. Moreover, a well-established institution, such as cash, which has proven to be successful and been developed further over hundreds of years, should not be abandoned without very careful consideration. At the same time, we do, of course, need to take a closer look at the efficiency or inefficiency of cash and new methods of payment.

The inclusion of benefits in the evaluation of payment instruments complicates the matter somewhat, especially as we are assessing a large number of qualitative and non-pecuniary factors, and externalities and network effects also play a role. This creates problems, especially when, as would seem meaningful, all parties involved in the payment process are included in the analysis. Cash, for example, is appreciated by consumers owing to its anonymity, whereas electronic payment systems allow retailers, in particular, to better assess the shopping habits of their customers.

At the same time, however, it is essential to take the benefits into account in order to provide a balanced assessment. Incorporating the benefits can have a marked impact on the relative evaluation of the individual payment methods (see Shampine, 2012).

Furthermore, while there are zero-sum games (“what one person gains, the other loses”) with sectoral costs within an accounting framework, this is rather the exception in terms of utility at the micro and macro levels. When benefits are included, excess burdens have to be taken into account and market prices become distorted. At all events, lower usage of cash should not necessarily be equated with greater (economic) efficiency (National Forum on the Payment System, 2015a; van Hove, 2016).

The assertion that cash is inefficient is often based exclusively on cost considerations and a purely partial-analytical or business perspective (eg Bloching, 2007; Guibourg & Segendorf, 2007). Benefit aspects are not taken into consideration. Moreover, the empirical evidence is by no means clear-cut. Even in the more business-oriented approaches with regard to costs, cash payments are not necessarily more expensive than cashless alternatives. In Germany, the cost of cash transaction is even lower than that of debit and credit cards. In terms of cost per turnover, debit cards are cheaper than cash, whereas credit cards are more expensive (Krueger & Seitz, 2014, Chapter 3; Thiele, 2016). In a study commissioned by the ECB covering several countries (Schmiedel et al, 2012), the findings did not reveal a uniform picture: in some countries, cash is the cheapest means of payment, whereas in other countries, cashless payment instruments are the cheapest.

Against this backdrop, this study attempts to systematically capture the benefits of cash, without providing quantitative estimates. It is structured as follows: Section 2 contains a brief overview of the literature and Section 3 presents a number of general remarks about cash and its benefits. Then, in Sections 4 and 5, the benefits of cash are discussed at the macroeconomic and microeconomic level. Section 6 broadens this perspective by incorporating societal aspects. Following on from this, Section 7 is dedicated to a critical discussion about the arguments put forward by those in favour of abolishing cash. Finally, Section 8 briefly summarizes the results and findings and draws a number of conclusions.

![]()

2Benefits of cash: an overview of the literature

If only costs are taken into consideration when comparing various payment instruments, it is implicitly assumed that the payments are otherwise completely identical (homogeneous). As every active user of payment instruments can testify, however, this is by no means the case. Payment instruments differ in terms of key characteristics, such as convenience, speed, traceability of the payment, etc. In the context of this study, we talk about the “benefits” of the different payment procedures.

While there are already numerous studies available on the costs of cash payment transactions (see Krueger & Seitz, 2014, Chapter 3), the benefits of cash are generally somewhat neglected in the literature. Garcia-Swartz et al (2006 a, b) calculate as part of a cost-benefit study – using two case studies from the grocery sector and electronics specialty stores – the marginal benefit (in monetary units) for consumers (“privacy”), the central bank (seigniorage, fees) and commercial banks (fees) for various (cash and cashless) transaction amounts in the United States and Australia. These are compared with the corresponding marginal costs. The benefits of the anonymity of cash payments and the protection of privacy are captured via “loyalty card discounts”. According to the authors, these discounts represent the implicit benefit gained as a reward for disclosing private information. They raise the question as to whether an additional electronic payment (eg by debit or credit card) would, in net terms, cost society more from a cost-benefit perspective than an additional paper-based payment (eg in cash). One of the important conclusions drawn by the authors is that it is essential from a welfare perspective to consider the costs and benefits of a payment instrument for all parties involved in the transaction. They do, however, also highlight the difficulties faced in quantifying the benefits. For this reason, and also with reference to other studies, a follow-up study (Stewart et al, 2014) focuses purely on the costs, without taking benefits into account: “In all cases, estimating the benefits of payments has been beyond the scope of these studies given the difficulties of defining and measuring these benefits.” (Stewart et al, 2014, 5). “The study does not measure the benefits associated with different payment instruments nor whether the structure of the market promotes innovation. Both these factors need to be considered when drawing policy implications from these numbers; increased use of the lowest-cost payment system or less use of the higher-cost systems does not necessarily imply better outcomes.” (Stewart et al, 2014, 12).

Simes et al (2006) adopt a similar, albeit much less detailed approach than Garcia-Swartz et al (2006 a, b) for Australia. Anonymity for the consumer, for instance, is mentioned as a benefit of cash, but is not incorporated in the analysis in quantitative terms. With regard to the benefits of cash, the focus is therefore solely on the benefits for central banks and commercial banks in the form of fees and seigniorage. The background to the study is the question whether, for allocative reasons, further regulation of the payments market is necessary (eg in the form of interchange fees).

In Banque Nationale de Belgique (2005) a survey is used to compare the (nonquantified) benefits of cash for retailers and consumers in Belgium with the (quantified) costs. General acceptance, the ease of use between individuals, anonymity and privacy protection, the ability to keep track of spending and prevent the build-up of excessive debt, and social integration are highlighted as being the main benefits. The study notes that various payment instruments offer specific advantages, which would suggest that consumers should be free to choose between different means of payment.

A critical general assessment taking due account of qualitative factors, benefits and social welfare considerations can be found in Shampine (2007, 2009). Particular emphasis is placed on the fact that it is practically impossible to determine every benefit and cost component (and the triggered external effects) for each party with any accuracy. Consequently, the results, including the ranking of the payment instruments, respond very sensitively to minor changes in the assumptions underlying the estimates. Estimating cash demand functions to determine the consumer surplus is also problematic given the limited data. Lam & Ossolinski (2015), for example, find a wide dispersion of results when estimating the willingness of Australian consumers to pay for card payments on the one hand and cash payments on the other. While, for example, 60% of the respondents were unwilling to pay a surcharge of 0.1%, only 5% of the respondents said that they were prepared to accept a surcharge of over 4%.

![]()

3Some general remarks

This section aims to address some of the features unique to cash, which should be taken into consideration when assessing the potential advantages of this form of payment.

First of all, it should be borne in mind that cash boasts a number of features which make it very difficult to develop a perfect electronic substitute (for more details, see Lepecq, 2015).

•Cash can be used anonymously;

•Cash can be used without the further involvement of service providers;

•The payer and the payee do not need to be online in any way, shape or form;

•Cash can be used for both small and large payments;

•The payment is simple, convenient and quick;

•Users do not receive proof of payment;

•The payment is definitive and final (it cannot be annulled and there is no way to lodge a complaint);

•Cash is relatively secure against counterfeiting.3

At present, there are no electronic payment instruments which offer all of these features. It is also hard to imagine that a payment instrument of this kind will ever exist.

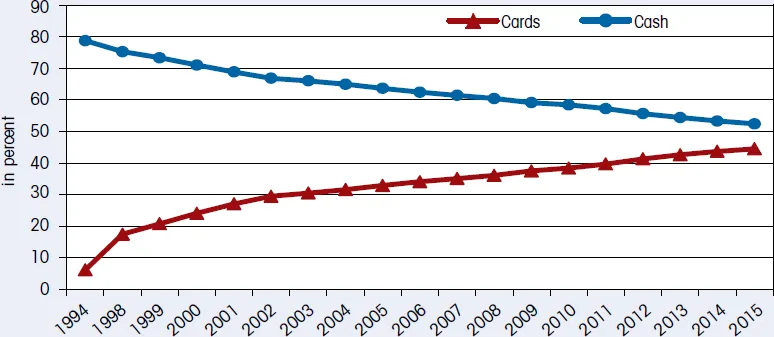

What functions does cash fulfil? These are derived from the general functions of money, which are the medium of exchange function, the store of value function and the unit of account function. It can generally be observed in all developed countries that the role of cash as a means of payment for “official” domestic purchases of goods and services has declined (see Figure 1 for the case of Germany and Bagnall et al, 2016, for an international comparison). Accordingly, the significance of cashless payment instruments, especially card payments, has increased in this respect.4

Figure 1: Share of cash and cards in retail trade

Source: EHI Retail Institute, own chart.

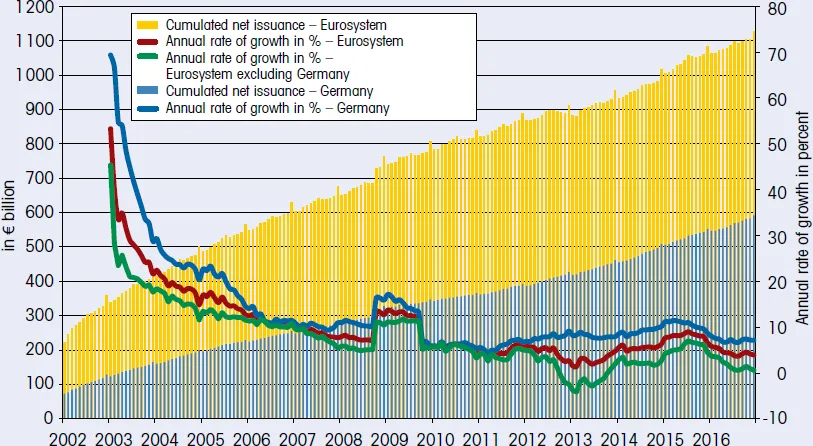

On the other hand, cash demand and the (net) issues of cash in the euro area and in Germany, for example, are steadily increasing, and also by a sizeable amount (see Figure 2). Consequently, other motives behind holding cash must have gained in importance. This could, on the one hand, be due to an increase in transaction demand in the domestic shadow economy (see section 7.1) or to a rise in foreign demand (see section 4.3). On the other hand, the store of value in the form of cash (hoarding) is likely to have gained in importance against the backdrop of subdued economic developments in some countries and very low interest rates (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2016b, 36).5 An increase in uncertainty and the fear of financial crises may also be factors in this development. The reasons behind this reflect security and precautionary motives (Arango et al, 2016; Alvarez & Lippi, 2009) as well as liquidity considerations (see Tanguy et al, 2015, for an overall assessment).

Figure 2: Circulation of euro banknotes

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank. | Notes: Year-on-year change. |

Cash is secure central bank money without any risk of default. It also has a very high degree of liquidity. Arango et al (2016) show that it can be optimal for consumers to hold a cash reserve for precautionary reasons. They verify their results, inter alia, for the case of Germany using payments diaries, which were kept as part of a study on payment behaviour. Alvarez & Lippi (2009) use a dynamic variant of the Baumol-Tobin model by expanding it to include random ATM cash withdrawals (at a low cost or free of charge). This results in a rationalisation of a precautionary cash reserve, as consumers also make cash withdrawals even when they already have cash in their wallet. This precautionary motive is all the more pronounced the greater the ratio between the average cash holding at the time of the withdrawal and the overall average cash holding. In the standard Baumol-Tobin model, this ratio is zero.

In the state-of-the-art monetary models on cash demand, eg cash-in-advance models (Lucas & Stokey, 1987), money-in-the-utility-function models (MIU) (Woodford, 2003, Chapter 2) or search models (Williamson & Wright, 2011), the velocity of circulation of cash is constant if foreign demand and store of value motives are left out of the analysis.6 The velocity of circulation does not therefore respond to a growing significance of alternative means of payment either. Consequently, it is not possible to explain the simultaneous decline in cash payments at the point of sale (see Figure 1) and the continuing rise in the total volume of cash in circulation in relation to GDP (Krueger & Seitz, 2014, 35). Jiang & Shao (2014), however, develop a two-sector model in which the demand for cash is purely for transaction purposes, whereby once a certain number of card payments is reached, the velocity of c...