eBook - ePub

Essential Effects

Water, Fire, Wind, and More

Mauro Maressa

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 286 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Essential Effects

Water, Fire, Wind, and More

Mauro Maressa

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Animate the world around you! Follow along with veteran Disney effects artist Mauro Maressa as he teaches you how to create and animate natural phenomena like water, fire, smoke, lightning, lava, mud, and wind. Essential Effects will help you plan, draw, design, and animate traditional 2D effects, taking your ideas all the way from rough sketch to finished product. Using a series of full-color visual breakdowns and diagrams, this book gives you a clear, concise understanding of what it takes to create credible, compelling effects in your own projects.

Key Features

- Build a strong foundation of observation and drawing skills that you can rely on for the rest of your career

- Tips and tricks for applying classic effects principles to computer-animated and CG projects

- Over 400 full-color images and diagrams for clear step-by-step learning

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Essential Effects è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Essential Effects di Mauro Maressa in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Media & Performing Arts e Animation. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

CHAPTER 1

A History of Effects in Animation

I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out till sundown,for going out, I found, I was really going in.—John Muir

Early on in animation, the animators did all their own effects as well as the character animation that may have been called for in the scenes they were working on. Often, the effects were more or less an afterthought to the gags the characters were acting out. Therefore the effects were usually haphazard and simplistic interpretations of the particular effect. Water was a flat mass with possibly some lines in it to indicate a directional flow that broke up like bits of torn paper when it hit a character. Smoke was a cycle of round shapes rising upward or covering the screen, the simplest and most elementary of designs. This was not a slight on the part of character animators. During the silent era, animators were cranking out one film per week. This left very little time for study or experimentation for improving the quality of effects in those shorts. The effects were done simply to convey the idea of fire, or water, or smoke, or whatever the gag called for, and the effect was usually on the same level as the characters, so there was very little chance of utilizing any camera effects, like diffusion or opacity.

Some of the very first drawn animation that I have found was on short films done by J. Stuart Blackton, considered by some to be the father of American animation. Blackton was producing animated sequences as early as 1900. These films were distributed by the Edison Studios. Humorous Phases of Funny Faces was released in 1906. Blackton used chalk on a blackboard smudged to make smoke “effects,” the earliest hand-drawn “animated effect” on film that I have found (see Figure 1.1).

Fig 1.1 J. Stuart Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces

Another early pioneer was Emile Cohl, who in 1908 produced Fantasmagorie, which had stick figures morphing into other figures. This has been credited as the first fully animated film. Camera effects started getting more creative (see Figure 1.2).

Fig 1.2 Emile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie

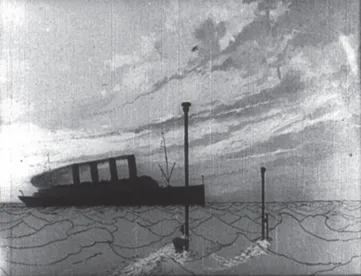

Windsor McCay produced perhaps his most famous film in 1914, Gertie the Dinosaur. But he also produced The Sinking of the Lusitania in 1918. The effects that McCay was able to imagine and achieve are, in my opinion, the best that had been done at the time—they would not be matched until the mid- to late-1930s. He truly was head and shoulders ahead of everyone else at the time (see Figure 1.3).

Fig 1.3 Windsor McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania

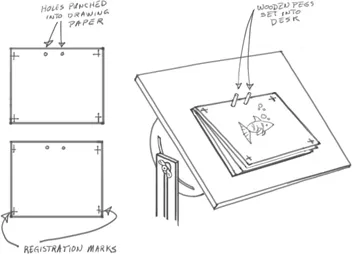

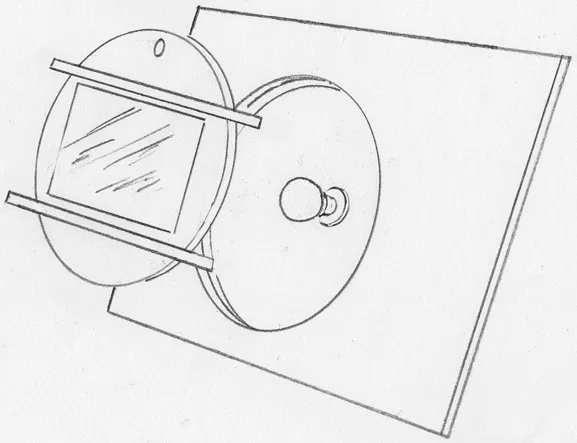

A typical animation desk setup was used in the early days of the animation process until the early 1920s. Windsor McCay set up his animation process like this, using tracing paper and transparent bond, so he could trace his backgrounds with each succeeding drawing (see Figure 1.4). Two holes punched in the paper would hold the paper in place, while the cross marks on the four corners were used to make certain all the drawings would line up as you animated each of the successive ones. You could use one method or the other, or both at once.

Fig 1.4 Windsor McCay’s animation setup

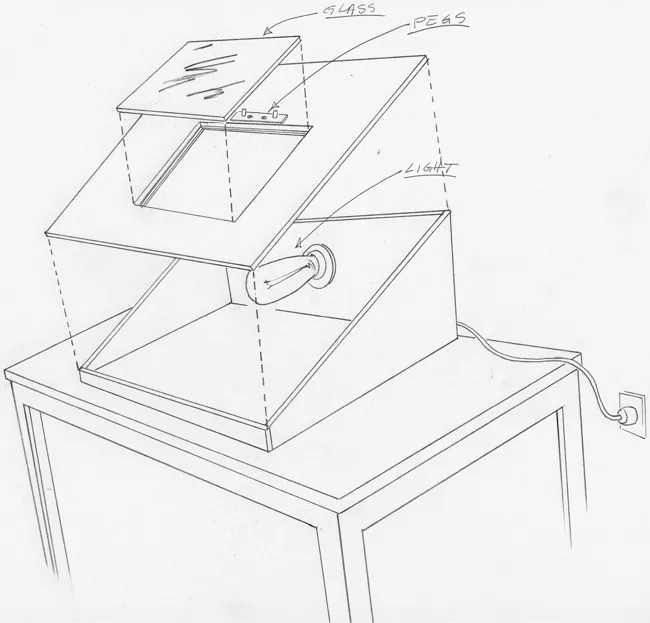

Meanwhile, within the industry there were advances in the way animation was being handled that advanced the medium. A French Canadian by the name of Raoul Barré and his partner Bill Nolan introduced the “peg” system. This would make it possible to register all drawings in exact alignment with each preceding and succeeding drawing, eliminating any shaking or giggling. The Barré–Nolan team also developed the long horizontal and vertical backgrounds. This would give the characters more freedom to move about the scenes without the need to trace the backgrounds onto each of the character drawings. It made it possible to use multiple layers of animated subjects and to incorporate effects in ways previously not possible, along with the introduction of the “cel system,” attributed to John Randolph Bray and Earl Hurd, who patented the process in 1914. (The cel system consisted of clear celluloid sheets onto which drawings were traced on the front in ink and later painted on the back, filling in the interiors of the silhouetted characters.) Bray is also credited with the system for breaking down the work—the assembly line, if you will, of the layout department, background, animator, assistant, and so on. These innovations, along with the invention of the glass disk in the center of the animator’s drawing board by Vernon George Stallings in the 1920s, further advanced the creative possibilities for animators. Now they could use a back light to see multiple levels at once and get precise one-to-one registration between characters as well as the effects around them (see Figure 1.5).

Fig 1.5 1920s animation desk with glass disk and box light

After further innovations to the animation disk, it evolved into the more familiar-looking round disk that the animator could turn and adjust for a more comfortable drawing position. The animation disk had only top pegs until the mid- to late 1930s; the addition of bottom pegs came later and gave the animators the ability to plot pans (see Figures 1.6 and 1.7).

Fig 1.6 More familiar disk with top and bottom pegs

Fig 1.7 My modern-day animation desk at Disney

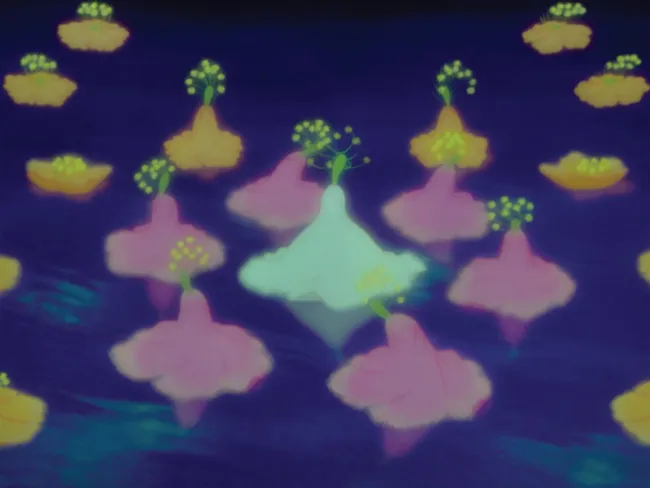

Animation started to rise to greater heights during the golden age of animation, roughly 1928–1967. Not only did the process get more sophisticated but also the stories got more complex in the telling and the visuals got more intricate. As the character animation became more sophisticated, the effects needed to rise to the occasion if they were to look and feel as if they belonged in the same environment as the characters, in order for the audience to believe that both effects and characters lived in the same environment. Otherwise the contrast would confuse the viewer and undermine the storytelling. In the mid- to late 1930s, a few effects specialists rose out of the character animation ranks. It was the Fleischer Studios and Walt Disney Studios that put more emphasis on the effects in their films. Disney led the way by using the series of shorts he made during that time. Silly Symphonies and the short The Old Mill used some ground-breaking innovations, such as the multiplane camera, that made for some truly memorable imagery. Disney not only used the shorts to train his character animators but also began training a small group of specialists with a knack for special effects. Early on, the Effects Department consisted of two animators and one assistant between them. Cyrus Young and Ugo D’orsi used their unique talents for animating effects to produce some of the best animated special effects ever done (see Figures 1.8 and 1.9).

Fig 1.8 “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” from Fantasia, animated by Ugo D’orsi

Fig 1.9 Fantasia, “Blossom Ballerina,” animated by Cyrus Young

These men, along with Josh Meador, who arrived in 1939 and who animated a lot of the water from the Monstro sequence in Pinocchio, raised the bar for...