- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Animate the world around you! Follow along with veteran Disney effects artist Mauro Maressa as he teaches you how to create and animate natural phenomena like water, fire, smoke, lightning, lava, mud, and wind. Essential Effects will help you plan, draw, design, and animate traditional 2D effects, taking your ideas all the way from rough sketch to finished product. Using a series of full-color visual breakdowns and diagrams, this book gives you a clear, concise understanding of what it takes to create credible, compelling effects in your own projects.

Key Features

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essential Effects by Mauro Maressa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Programming Games. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A History of Effects in Animation

I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out till sundown,for going out, I found, I was really going in.—John Muir

Early on in animation, the animators did all their own effects as well as the character animation that may have been called for in the scenes they were working on. Often, the effects were more or less an afterthought to the gags the characters were acting out. Therefore the effects were usually haphazard and simplistic interpretations of the particular effect. Water was a flat mass with possibly some lines in it to indicate a directional flow that broke up like bits of torn paper when it hit a character. Smoke was a cycle of round shapes rising upward or covering the screen, the simplest and most elementary of designs. This was not a slight on the part of character animators. During the silent era, animators were cranking out one film per week. This left very little time for study or experimentation for improving the quality of effects in those shorts. The effects were done simply to convey the idea of fire, or water, or smoke, or whatever the gag called for, and the effect was usually on the same level as the characters, so there was very little chance of utilizing any camera effects, like diffusion or opacity.

Some of the very first drawn animation that I have found was on short films done by J. Stuart Blackton, considered by some to be the father of American animation. Blackton was producing animated sequences as early as 1900. These films were distributed by the Edison Studios. Humorous Phases of Funny Faces was released in 1906. Blackton used chalk on a blackboard smudged to make smoke “effects,” the earliest hand-drawn “animated effect” on film that I have found (see Figure 1.1).

Fig 1.1 J. Stuart Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces

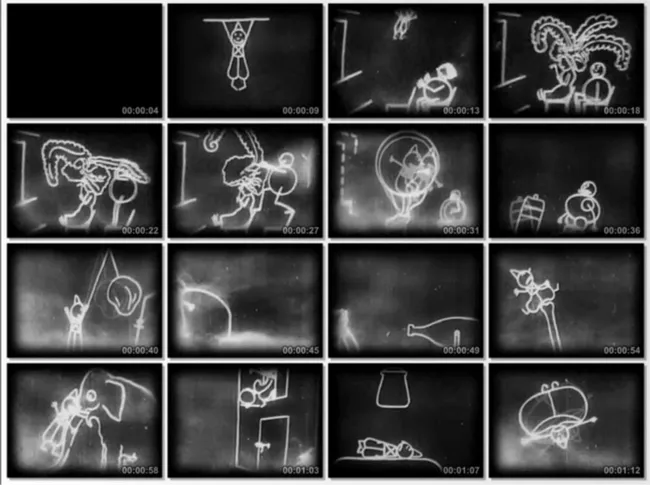

Another early pioneer was Emile Cohl, who in 1908 produced Fantasmagorie, which had stick figures morphing into other figures. This has been credited as the first fully animated film. Camera effects started getting more creative (see Figure 1.2).

Fig 1.2 Emile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie

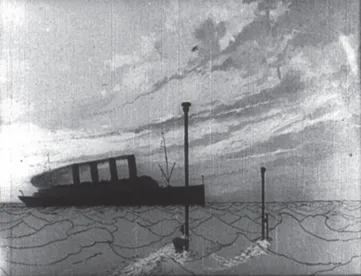

Windsor McCay produced perhaps his most famous film in 1914, Gertie the Dinosaur. But he also produced The Sinking of the Lusitania in 1918. The effects that McCay was able to imagine and achieve are, in my opinion, the best that had been done at the time—they would not be matched until the mid- to late-1930s. He truly was head and shoulders ahead of everyone else at the time (see Figure 1.3).

Fig 1.3 Windsor McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania

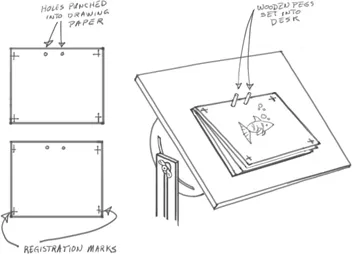

A typical animation desk setup was used in the early days of the animation process until the early 1920s. Windsor McCay set up his animation process like this, using tracing paper and transparent bond, so he could trace his backgrounds with each succeeding drawing (see Figure 1.4). Two holes punched in the paper would hold the paper in place, while the cross marks on the four corners were used to make certain all the drawings would line up as you animated each of the successive ones. You could use one method or the other, or both at once.

Fig 1.4 Windsor McCay’s animation setup

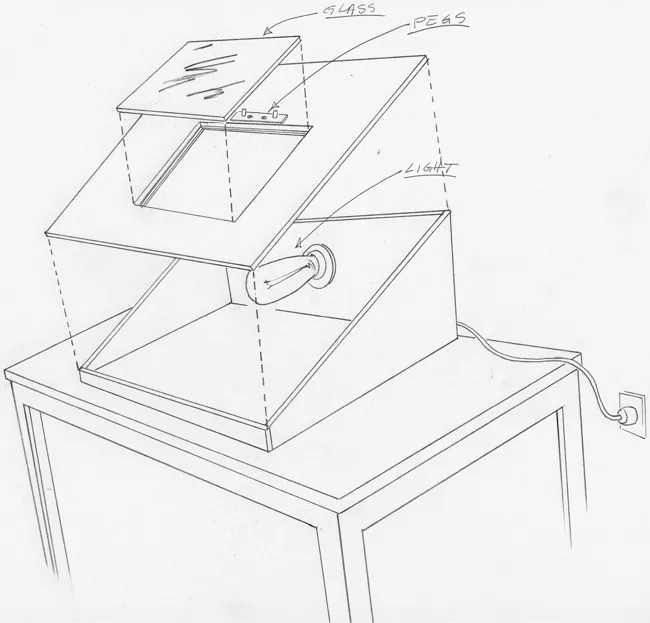

Meanwhile, within the industry there were advances in the way animation was being handled that advanced the medium. A French Canadian by the name of Raoul Barré and his partner Bill Nolan introduced the “peg” system. This would make it possible to register all drawings in exact alignment with each preceding and succeeding drawing, eliminating any shaking or giggling. The Barré–Nolan team also developed the long horizontal and vertical backgrounds. This would give the characters more freedom to move about the scenes without the need to trace the backgrounds onto each of the character drawings. It made it possible to use multiple layers of animated subjects and to incorporate effects in ways previously not possible, along with the introduction of the “cel system,” attributed to John Randolph Bray and Earl Hurd, who patented the process in 1914. (The cel system consisted of clear celluloid sheets onto which drawings were traced on the front in ink and later painted on the back, filling in the interiors of the silhouetted characters.) Bray is also credited with the system for breaking down the work—the assembly line, if you will, of the layout department, background, animator, assistant, and so on. These innovations, along with the invention of the glass disk in the center of the animator’s drawing board by Vernon George Stallings in the 1920s, further advanced the creative possibilities for animators. Now they could use a back light to see multiple levels at once and get precise one-to-one registration between characters as well as the effects around them (see Figure 1.5).

Fig 1.5 1920s animation desk with glass disk and box light

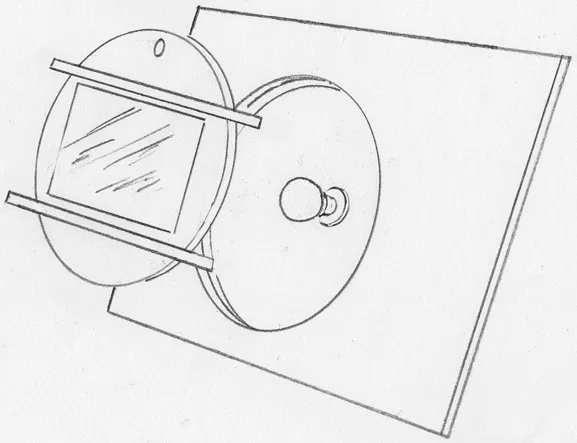

After further innovations to the animation disk, it evolved into the more familiar-looking round disk that the animator could turn and adjust for a more comfortable drawing position. The animation disk had only top pegs until the mid- to late 1930s; the addition of bottom pegs came later and gave the animators the ability to plot pans (see Figures 1.6 and 1.7).

Fig 1.6 More familiar disk with top and bottom pegs

Fig 1.7 My modern-day animation desk at Disney

Animation started to rise to greater heights during the golden age of animation, roughly 1928–1967. Not only did the process get more sophisticated but also the stories got more complex in the telling and the visuals got more intricate. As the character animation became more sophisticated, the effects needed to rise to the occasion if they were to look and feel as if they belonged in the same environment as the characters, in order for the audience to believe that both effects and characters lived in the same environment. Otherwise the contrast would confuse the viewer and undermine the storytelling. In the mid- to late 1930s, a few effects specialists rose out of the character animation ranks. It was the Fleischer Studios and Walt Disney Studios that put more emphasis on the effects in their films. Disney led the way by using the series of shorts he made during that time. Silly Symphonies and the short The Old Mill used some ground-breaking innovations, such as the multiplane camera, that made for some truly memorable imagery. Disney not only used the shorts to train his character animators but also began training a small group of specialists with a knack for special effects. Early on, the Effects Department consisted of two animators and one assistant between them. Cyrus Young and Ugo D’orsi used their unique talents for animating effects to produce some of the best animated special effects ever done (see Figures 1.8 and 1.9).

Fig 1.8 “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” from Fantasia, animated by Ugo D’orsi

Fig 1.9 Fantasia, “Blossom Ballerina,” animated by Cyrus Young

These men, along with Josh Meador, who arrived in 1939 and who animated a lot of the water from the Monstro sequence in Pinocchio, raised the bar for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A History of Effects in Animation

- Chapter 2: What Exactly Is a Traditionally Animated Effect?

- Chapter 3: What Does It Take to Become an Effects Animator?

- Chapter 4: Thumbnails

- Chapter 5: Caricaturing of an Effect

- Chapter 6: Perspective

- Chapter 7: Water

- Chapter 8: Fire

- Chapter 9: Smoke

- Chapter 10: Dust

- Chapter 11: Tones, Shadows, and Highlights

- Chapter 12: Rocks, Props, and Things

- Chapter 13: Trees, Leaves, and Grass

- Chapter 14: Pixie Dust, Mattes, and Slot Gags

- Chapter 15: Fantasy Effects and Ectoplasm

- Chapter 16: Lava and Mud

- Chapter 17: Lightning and Electricity

- Chapter 18: Explosions

- Chapter 19: Fire Hoses and Faucets

- Chapter 20: Straight Ahead and Pose to Pose

- Chapter 21: Bouncing Ball

- Chapter 22: Exposure Sheets

- Index