![]()

1

Setting the scene

Introduction

Languages change – constantly, inevitably. Unfortunately, this is a little bit hard to see when you just look at present-day English for example. The language you use every day doesn’t change … Or does it? You’ll know the answer by the end of this book.

Let’s start with a little experiment. There is a very famous English text about 1,000 years old, from the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.1 The text describes the arrival of dragons in northern England in 793:

Ann. dccxciii. Her ƿæron reðe forebecna cumene ofer norðhymbra land. 7 þæt folc earmlic breʒdon þæt ƿæron ormete þodenas 7 liʒrescas. 7 fyrenne dracan ʒæron ʒeseʒene on þam lifte fleoʒende.

‘A.D. 793. This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery, dragons flying across the firmament.’

You will probably recognize a word or two (like cumene ‘come’, land ‘land’ or dracan ‘dragons’), but it is very unlikely that you can read this original Old English text without any formal training – even though this is supposedly the same language you are reading right now!

Let’s fast forward a bit. Compare the example above to the experience of reading a little bit of Geoffrey Chaucer, one of the most famous English poets of the later Middle Ages (he died in 1400). Chaucer describes a scene in which a woman who married five different men debates and laments the fact that apparently the Bible disapproves of such behaviour:

“Thou hast yhad five housbondes,” quod he [Jesus],

“And that ilke man that now hath thee

Is nat thyn housbonde.” Thus saide he certain.

What that he mente therby I can nat sayn,

But that I axe why the fifthe man

Was noon housbonde to the Samaritan?

How manye mighte she han in mariage?

Yit herde I nevere tellen in myn age

Upon this nombre diffinicioun.

Men may divine and glosen up and down,

But wel I woot, expres, withouten lie,

God bad us for to wexe and multiplye:

That gentil text can I wel understonde.

(The Canterbury Tales, The Wife of Bath’s Prologue)

“Now you have had five husbands,” he [Jesus] said,

“But he who has you now, I say instead,

Is not your husband.” That he said, with certainty,

But what he meant thereby I cannot say;

But I must ask, why the fifth man

Was no husband to the Samaritan?

How many [men] is she allowed to have in marriage?

I’ve never heard it said in all my time

How this number is defined;

Men may divine and gloss up and down,

But I know well, expressly, without lie

God bade us to increase and multiply –

That noble text I understand well.

The Chaucer text will probably look a lot more familiar and less confusing than the Old English text. And yet you would still need to have some training in Middle English or an amazing guessing ability in order to read and fully understand it. This is clearly not present-day English yet. Let’s move ahead another 200 years and read some Shakespeare, around 1600:

BEATRICE

I wonder that you will still be talking, Signior

Benedick: nobody marks you.

BENEDICK

What, my dear Lady Disdain! are you yet living?

BEATRICE

Is it possible disdain should die while she hath

such meet food to feed it as Signior Benedick?

Courtesy itself must convert to disdain, if you come

in her presence.

BENEDICK

Then is courtesy a turncoat. But it is certain I

am loved of all ladies, only you excepted: and I

would I could find in my heart that I had not a hard

heart; for, truly, I love none.

BEATRICE

A dear happiness to women: they would else have

been troubled with a pernicious suitor. I thank God

and my cold blood, I am of your humour for that: I

had rather hear my dog bark at a crow than a man

swear he loves me.

BENEDICK

God keep your ladyship still in that mind! so some

gentleman or other shall ’scape a predestinate

scratched face.

BEATRICE

Scratching could not make it worse, an ’twere such

a face as yours were.

(Much Ado about Nothing, I.1)

At last we have reached a point where the language looks a lot more like present-day English. It may still be hard to understand, but this is perhaps due to the style of the author rather than the language itself. Here you probably only have to guess the meaning of a few words and phrases (meet in meet food is an archaic word for ‘fitting’ or ‘convenient’, and humour in Shakespeare does not mean ‘banter, playfulness’, but rather refers to the theory of four body humours, or temperaments). In contrast to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, you should be able to get an idea of what is going on instead of just guessing a few words!

So this little experiment shows nicely that languages change. English underwent some drastic and radical changes between ca. 700 CE and 1600 CE (a period of almost 1,000 years!). In fact, these changes seem to be so radical that some people would even question whether Old English is related to present-day English – which is also why some people prefer to call it Anglo-Saxon rather than Old English.

The same can also be said about Latin and its “daughter” languages Spanish, French, Italian and Portuguese. All these languages go back to Latin as their source, or “mother language”. Hence, this is called the family of Romance languages, as Romance is derived from Rome, the capital of the Roman Empire, and not from romantic. But it is difficult to see the history and connections (relations) between all of these languages at first glance. The following example gives you a famous line from the Ten Commandments (“Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain”; Exodus 20:7, originally written in Hebrew) in Latin and in French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese (and English as a gloss). Latin is usually considered to be the “mother” of these four modern “daughter” languages. The development of the daughter languages also probably took more than 1,000 years, just like Modern English.

| Latin: | non adsumes nomen Domini Dei tui in vanum nec enim habebit insontem Dominus eum qui adsumpserit nomen Domini Dei sui frustra. |

| French: | Tu ne prendras point le nom de l’Eternel, ton Dieu, en vain; car l’Eternel ne laissera point impuni celui qui prendra son nom en vain. |

| Italian: | Non usare il nome dell’Eterno, ch’è l’Iddio tuo, in vano; perché l’Eterno non terrà per innocente chi avrà usato il suo nome in vano. |

| Spanish: | No tomarás el Nombre del SEÑOR tu Dios en vano; porque no dará por inocente el SEÑOR al que tomare su Nombre en vano. |

| Portuguese: | Não tomarás o nome do Senhor teu Deus em vão; porque o Senhor não terá por inocente aquele que tomar o seu nome em vão. |

| English: | Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain. |

| (Exodus 20:7) |

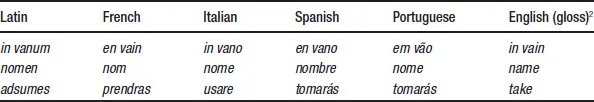

Just like with our English examples, some similarities between the different languages can be still be found, but many things have changed drastically. Latin seems to have changed a lot on its way to modernity. Table 1.1 gives you a first overview. Why don’t you try to find some examples for this table yourself?

You might still think now that language change is essentially a matter of the past, something that affected languages more than 1,000 years ago, when we still had knights, Vikings, gladiators and so on. The fact that we can still read Shakespeare, but not Old English, even supports such a view. However, this is far from the truth.

Languages are in a constant state of flux, today just as in the past – even though we might not always notice it. There are a couple of words that used to be very popular not too long ago in 20th century English: do you know what a church key is? In the 1960s before pop top cans, this was a special opener to puncture the tops of soda and beer cans. A fox in the 1970s was not only an animal, but also a sexy looking woman or man. On the other hand, nobody in the 1960s or 1970s knew the words DVD, google, or selfie.

Pronunciation has also changed. Words like applicable and primarily used to be stressed on the first syllable: 'applicable and 'primarily. Today, we tend to stress them as ap 'plicable and pri'marily. Many varieties of present-day English are currently changing from street to shtreet. And is it student or stjudent – or even shtjudent? Ask or aks? To cut a long story short, there is good evidence that English and all other living languages are still changing and will continue to do so. You will find many more examples for this throughout the book.

Table 1.1

Some formal correspondences between different Romance languages

We should emphasize, though, that languages do not change at a constant rate. As the overall history of English shows, there can be periods of speeding up and periods of slowing down. From the time of the dragon in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle through to the 17th century, and even the 18th century, changes were complex and rapid. As a consequence, people in, say, the 1700s could not read with ease the literature of three centuries earlier. The extract above from Chaucer would have presented difficulties, just as it does today. And language from a still earlier time prompted even Chaucer to make the observation: “[y]e knowe ek that in forme of speche is change” (‘you know also that in (the) form of speech (there) is change’), noting the “wonder nyce and straunge” (‘wonderfully curious and strange’) nature of early English words (in Troilus and Criseyde II, 22ff). And yet Modern English readers have little trouble reading texts of the 1700s. The language of Jonathan Swift or Jane Austen is stylistically different and has some unfamiliar looking vocabulary, but it is recognizably Modern English.

The fact that languages change is a great concern to many people, and we find frequent complaints in the media that languages aren’t what they used to be. People mourn the loss of culture and language standards, especially in children and young adults. From this perspective, languages change (i.e. “decline”) because younger generations lack the competence, precision and strictness to speak their language properly. Kids are simply too lazy. Whether the advocates who see language as being in decline are right or wrong is a question we will discuss later on in this c...