![]()

1

In Search of Vermeer

A great work of art is the transposition of experiences … founded upon an artist’s unique inspiring genius, and … we, the audience, ourselves regard the encounter with the work as our experience.

Joseph Leo Koerner, Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape

I The Street Where He Lived

Vermeer’s House

The Little Street presents one of the many riddles of the Sphinx of Delft (Plate 1). Several attempts have been made to identify the location portrayed in Vermeer’s painting, all of which present fundamental problems. One scholar recently declared that the scene “has never been identified, and the probability is slight that it ever will be.”1 In my view, Vermeer’s painting portrays his own house and family. This seemingly obvious solution involves complex evidence and distills the primary argument of this book: Vermeer’s self-conscious use of his surroundings and personal experience in his paintings constitutes a crucial, yet still unrecognized dimension of his compelling naturalism. The Little Street also distills Vermeer’s art and life: his house, the street where he lived, his family’s situation within Delft society, the rooms on which he based his interiors, lived, and worked, and his family members as models. His composition furthermore provides an occasion to address his relation to other artists, interpretations of Dutch genre painting, the meaning of art, and the task of art history. This chapter concludes with an interpretation of Vermeer’s greatest work, his View of Delft (Plate 16), and draws on the history of scholarship including Thoré and Proust to underscore a secondary argument of this book: Vermeer’s paintings are primarily of interest as works of genius, and their meaning is articulated belatedly through a cumulative, imperfect process of discovery, in search of Vermeer.

As a beautiful and original work of art, we need only look at The Little Street. Yet if we seek to address the various attempts to identify the location, we are gradually drawn into a detective story worthy of Poe’s Inspector Dupin; as with the purloined letter, the solution also lies in plain sight, beneath our nose. As a result of our efforts, we end up situating Vermeer in his own little world and, uncannily, recognize that he was already situating himself, even us, formulating the questions about art that we are now asking. Lastly, we discover more about why his painting is beautiful and original, and learn to love it even more.

The Little Street is the English translation of the modern Dutch title of Vermeer’s painting, ‘t Straatje, which can also mean “the alley,” although neither the alleyway at the center of the composition nor the short stretch of cobblestone street in the foreground are the primary subject. In fact, the composition has no obvious theme. A woman seated on a low stool in the threshold of a house is sewing, getting fresh air, and keeping an eye on a boy and girl crouching on the front stoop, absorbed in their play. The dirty white-washed wall above the front bench lends the house a shabby, lived-in feel. Elegant high windows grace its aged façade, which contains numerous patches of repaired brick and iron reinforcements. Around the corner, at the back of the alley, a servant fetches water from a barrel. A smaller house on the left is partly hidden by ivy; the arch-shaped doorway beside it leads to yet another house in the interior courtyard, and behind it we glimpse the top of another house on the next street, framed by a cloudy sky.

There is only one major correction in the composition: X-rays reveal the traces of a figure seated at the front of the alley, barely visible in the original, whose pose echoes the woman in the threshold in reverse .2 This was likely Vermeer’s first version of the figure, presumably observed from life. By displacing her to the threshold of the house, he improved his composition, with each of the figures framed by their own appropriate space, and allowed the alley to assume its function as a perspective opening, what the Dutch called a doorkijkje [little through-view]. The kneeling children were furthermore painted thinly over the front stoop visible underneath, so they must have been added later, probably likewise observed from life, and were perhaps part of the reason for or a result of displacing the woman to the doorway. Vermeer could have taken months to complete his composition, not in order to paint, but in order not to paint, and instead to think through his conception. Although the result of a long process, the final version looks more natural to us, as a family absorbed in activities around their home.

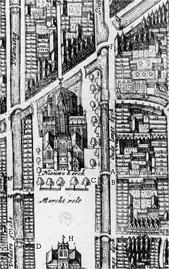

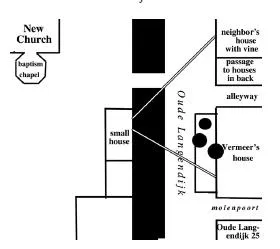

The scene was first identified back in 1925 by the Delft archivist L. Bouricius as Vermeer’s house on the east side of Delft’s main square. However, Bouricius mistakenly identified Vermeer’s house as Oude Langendijk no. 25, on the west side of the small cross street De Molenpoort, which he equated with the alley in Vermeer’s scene (Figs 1–2B, 4). 3 In fact, Vermeer’s house stood on the east side of De Molenpoort, on the spot now occupied by the vestry of the Church of Maria and Jesse (Figs 1–2A, 3).4

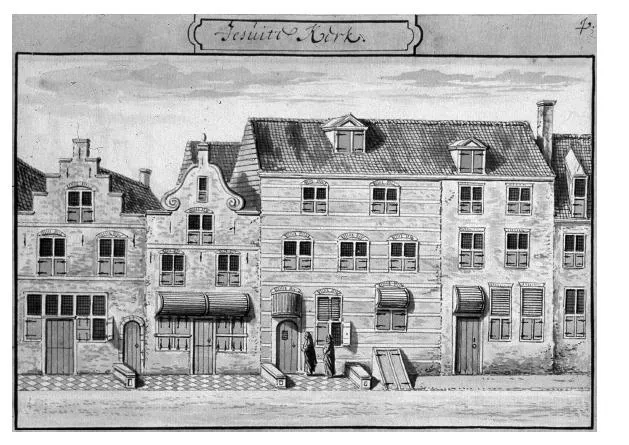

Another scholar proposed that Vermeer painted the view across the canal from the back of his parents’ home located above the tavern Mechelen, on the other side of the main square (Figs 1–2D, 6). According to this theory, The Little Street showed the old men’s home with its arched doorway on the left and the old women’s home with some inhabitants on the right, which was partly destroyed in 1661 to build the St Luke or painters’ guildhall (Figs 1–2E, 7).5 But the old women’s home was located elsewhere, whereas the St Luke’s Guild moved into an existing sixteenth-century church building, depicted in Johannes Blaeu’s 1649 map of Delft (Fig. 1E) .6 The mistaken theory nevertheless continues to surface in scholarship and has now influenced the modern face of Delft through the “Vermeer Center” in the reconstructed St Luke’s Guild.7 Most recently, an archeological report on the foundations discovered on the north side of De Nieuwe Langendijk at nos 22–26 identified these with the buildings in The Little Street (Figs 1–2G).8 However, the canal here has streets on either side, so the location could not have been observed from the near and low viewpoint alongside the canal indicated in Vermeer’s painting, among other problems .9

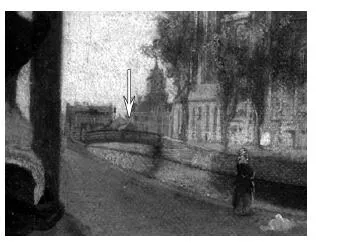

What is most obvious or closest to home is often the easiest to overlook. The first identification of the scene as Vermeer’s house was in my view correct, despite the wrong address: De Molenpoort is located just out of view on the right (Figs 1–2A, 3). As Bouricius recognized, Vermeer must have depicted his scene from a low second-story room of a merchant’s small house across the canal, located at a slight diagonal to his own house, as evident from the visible left wall of the alley (Fig. 8). The small house across the canal is depicted in maps, just down from the bridge, and in the background of Carel Fabritius’s View in Delft (Figs 1–2C, 9, 11, Plate 16). A photograph from the second-story window of the vestry of the Church of Maria and Jesse, corresponding to the view from Vermeer’s studio window, shows a taller modern house in the same place, with houses on either side, and the tip of the Old Church behind poking up in the background (Fig. 5). The slightly open window on the low second story, obscured in the photograph by Christmas decorations hung across the canal, corresponds roughly to the window in the house on the same spot from which Vermeer composed The Little Street.

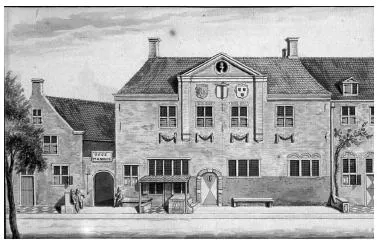

A map of Delft made after the great fire of 1536, which consumed four-fifths of the town, indicates that Vermeer’s house lay on the border of the neighborhoods that were saved.10 The early sixteenth-century climbing crenellated gable in his painting, which was already rare in the seventeenth century, the slightly off-center threshold, and numerous repairs of the aged façade testify to a lone survivor of an earlier era.11 The makeshift alleyway and arched entranceway next door were presumably built in the wake of a house destroyed in the fire, and the piecemeal construction of the smaller house on the left indicates a reconstruction.12 Vermeer’s neighborhood was also called the “papists’ corner” because Catholic families such as his in-laws and Jesuits owned most of the houses. Catholicism was illegal in the Protestant Dutch Republic, but tacitly tolerated by local authorities, partly because they were given money to turn a blind eye.13 An early eighteenth-century drawing portrays two cloaked priests entering a hidden church in a large four-story building on Vermeer’s street (Fig. 10).14 The house was extended by an annex on the right in 1678. Vermeer’s house is assumed to be the one next to the annex, cut off at the right edge of the drawing, with its long side facing the street, or one just beyond. In my view, the house at the right edge of the drawing replaced Vermeer’s.

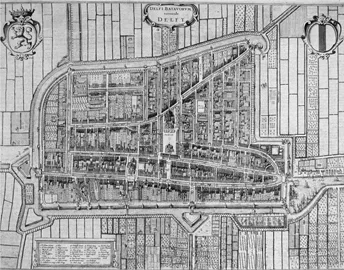

Blaeu’s 1649 map, which was presumably a rough approximation of the situation at the time, indicates several uniform houses with their gables facing De Oude

1 Johannes Blaeu, Map of Delft, 1649, Delft, Gemeentearchief.

Detail: market square with sites

A Vermeer’s house on De Oude Langendijk

B House across De Molenpoort

C Low house across the canal

D The tavern Mechelen

E St Luke’s (painters’) Guild

F Viewpoint of C. Fabritius, View in Delft

G Nieuwe Langendijk 22–26

H Town Hall

2 Aerial view of Delft’s main square with open-air covered market, 1925, Delft, Gemeentearchief.

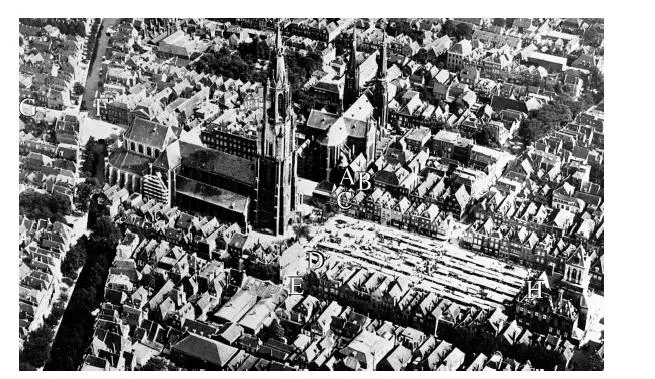

3 Site of Vermeer’s house with Vermeer cube (A).

4 Neighbor’s house across De Molenpoort (B).

5 House across the canal seen from Vermeer’s “studio window” (C).

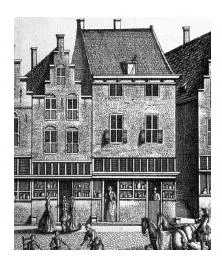

6 After A. Rademaker?, Mechelen (D) ca. 1700, Delft,Gemeentearchief.

7 Rademaker?, St Luke’s Guild (E) ca. 1700, Delft, Gemeentearchief.

Langendijk at the east side of De Molenpoort nearer to the New Church—Vermeer’s house on the corner is shown east of the bridge, whereas the church vestry that replaced his house is found slightly west of the bridge (Figs 1A, 3). A more detailed “figurative” map from 1675–8 shows Vermeer’s house on the corner with its short gable side facing De Oude Langendijk, next to a house with its long side facing the street, corresponding to the house with the hidden church and its annex shown in the drawing (Fig. 11). The figurative map mistakenly omitted the bridge over the canal.

The history of Vermeer’s little stretch of street can accordingly be reconstructed as follows. Sometime after he painted The Little Street, the smaller ivy-covered house

8 Scheme of viewpoint in The Little Street.

9 Carel Fabritius, View in Delft, 1652, detail: woman,swan, small house across canal.

10 A. Rademaker, Jesuit Church in Delft, ca. 1700, Delft, Gemeentearchief.

on the left and the house beyond it were demolished and replaced by the large building with the hidden Jesuit church seen in the drawing. In ...