![]()

DAY ONE

Tuesday

February 23, 1836

Prologue

IT WAS A LATE morning following the fandango on February 22 in honor of Señor Jorge Washington’s birthday. Most of the Texians lived in Béxar proper as opposed to the Alamo. The Texians awoke that morning to the sound of cart wheels squeaking and oxen lowing as the majority of San Antonio’s citizens left as quickly as possible. The rumor had spread the previous evening that the army of Santa Anna was bivouacked on the León River, only eight miles away, and would attack the town at any time.

Travis started detaining citizens, demanding their destination and reason for departure. Their destination was simple—out of Béxar—and the reason was just as simple. No doubt the citizens remembered the last insurrection in San Antonio in 1813. The Spanish Army executed Béxareños alongside the revolutionaries, and those who slipped by the executioner often had their property confiscated.

Travis posted a lookout in the tower of the San Fernando Church on Main Plaza. Just after noon the bell rang, and the sentry alarmed, “The enemy are in view.” Travis sent John Sutherland and John Smith to reconnoiter. A short distance out of town, they came upon the Dolores Cavalry Regiment preparing to attack the town. Upon the return of the couriers, Travis ordered a full retreat into the Alamo.

During the withdrawal several head of cattle and bushels of corn were purchased from the residents of La Villita on the Alamo side of the San Antonio River. As the gates closed behind the Texians, the lead elements of the Mexican Army’s Vanguard Brigade entered the west side of San Antonio. Some of the brigade units pushed down the river to clear the Mission Concepción in case more Texians were located there.

The Mexicans raised a blood-red banner over the San Fernando Church, as an indicator that no quarter—no mercy—would be offered. Immediately Texians, possibly ordered by Travis, fired a cannon toward the city as a response to the Mexicans’ banner. Jim Bowie, perhaps more sensitive to the Mexican character, dispatched a messenger asking for a parley and apologizing for the cannon shot. Travis, upon learning this, sent his messenger to the Mexicans. Both couriers received the same answer: surrender at discretion or be put to the sword. The cannon fired again in final response to the Mexicans’ demand.

In analysis of the above events, luck was definitely with the Texians on the first day. This was no sneak attack by the Centralists. The terrain and climate were harsh but hardly insurmountable. The Texians knew almost from the moment Santa Anna crossed the Río Grande and did little to prepare.

After the message from Blas Herrera, a rebel Tejano scout, on February 11, little active reconnaissance occurred until Sutherland and Smith’s patrol on the 23d. The eighteen to twenty-one cannon of the Alamo more than likely had not been ranged and target reference points noted, and the Centralists found a large cache of weapons in Bèxar that was left behind in the rush. The suburbs or barrios of La Villita extended all the way up to the south wall of the Alamo, and the Federalists had not cleared the fields of fire. There was no food available, but fortunately there were beeves belonging to the Esparzas and other locals that the Texians were able to acquire. The jacales were scavenged for corn, a staple in the local diet.

The Texians disregarded what intelligence they received and had little respect for soldado (Mexican soldier) ability.

S. Rodríguez

One morning early a man named Rivas called at our house and told us that he had seen Santa Anna in disguise the night before looking in on a fandango on Soledad Street. My father being away with Houston’s army, my mother undertook to act for us and decided it was best for us to go into the country to avoid being here when General Santa Anna’s army should come in. We left in oxcarts, the wheels of which were made of solid wood. We buried our money in the house. . . . (Matovina: 114-115)

Almonte

. . . General [Ramírez y] Sesma arrived at [the Alazón Creek, by] 7:00 A.M., and did not advance to reconnoiter [San Antonio] because he expected an advance of the enemy which was about to be made according to accounts given by a spy of the enemy who was caught. There was water, though little, in the stream of las lomas del Alazón. (SHQ 48:16-17)

San Luis Potosi

Location, Béxar. General Ramírez [y Sesma] having advanced with sixteen cavalrymen came into view of [San Antonio] at seven in the morning, at which hour none of the enemy knew of our arrival. . . . (McDonald and Young: 1)

de la Peña

On the 23rd General Ramírez y Sesma advanced at dawn toward Béxar with one hundred horsemen; although he had approached them [Texians] at three o’clock in the morning the enemy was unaware of our arrival.1 (Perry:38)

Almonte

Tuesday at 7:30 A.M. the [main] army was put in march [from the Medina]—To the Potranca [Creek] 1½ leagues, to the creek of León or Del Wedio, 3½ leagues—To Béxar 3 leagues, in all 8 leagues.2 (SHQ 48:16-17)

Sutherland

On the morning of the twenty-third the inhabitants [of San Antonio de Béxar] were observed to be in quite an unusual stir. The citizens of every class were hurrying to and fro through the streets with obvious signs of excitement. Houses were being emptied, and their contents put into carts and hauled off.

Much of the poorer class, who had no better mode of conveyance, were shouldering their effects and leaving on foot.

These movements solicited investigation. Orders were issued [by Travis] that no others be allowed to leave the city, which had the effect of increasing their commotion. Several [citizens] were arrested and interrogated as to the cause of the movement, but no satisfactory answer could be obtained. The most general reply was that they were going out to the country to prepare for the coming crop. This excuse, however, availed nothing, for it was not to be supposed that every person in the city was a farmer. Colonel Travis persisted in carrying out his order and continued the investigation. Nine o’clock came and no discoveries were made. Ten o’clock in like manner passed and finally the eleventh hour was drawing near and the matter was yet a mystery. It was hoped by Colonel Travis that his diligent investigation and strict enforcement of the order prohibiting the inhabitants from leaving the city would have the effect of frightening them into a belief that their course was not the wisest for them to pursue; that he, provoked by their obstinacy in refusing to reveal the true cause of the uneasiness, would resort to measures which might be more distasteful than any which would probably follow an open confession. But in that he was disappointed. The treacherous wretches persisted in their course, greatly to his discomfiture all the while.3 (Sutherland: 15-17)

Ruiz

. . . at eight o’clock in the morning, [the Texians] learned that the Mexican army was on the banks of the Medina River, they [the Texians] concentrated in the fortress of the Alamo. (Texas Almanac, 1860:56)

Loranca

About nine in the morning, President Santa Anna arrived and joined with his staff the column [under Ramírez y Sesma] which was now in the vicinity of San Antonio.4 (San Antonio Express, June 23, 1878)

Santa Anna

Béxar was held by the enemy and it was necessary to open the door to our future operations by taking it. It would have been easy enough to have surprised it, because those occupying it did not have the faintest news of the march of our army.5 I entrusted, therefore, the operation to one of our generals, who with a detachment of cavalry, part of the dragoons mounted on infantry officers’ horses, should have fallen on Béxar in the early morning of February 23, 1836. My orders were concise and definite. I was most surprised, therefore, to find the said general [Ramírez y Sesma] a quarter of a league from Béxar at ten o’clock of that day, awaiting new orders. This, perhaps, was the result of inevitable circumstances; and, although the city was captured, the surprise that I had ordered to be carried out would have saved the time consumed and the blood shed later in the taking of the Alamo. (Castañeda: 12-13)

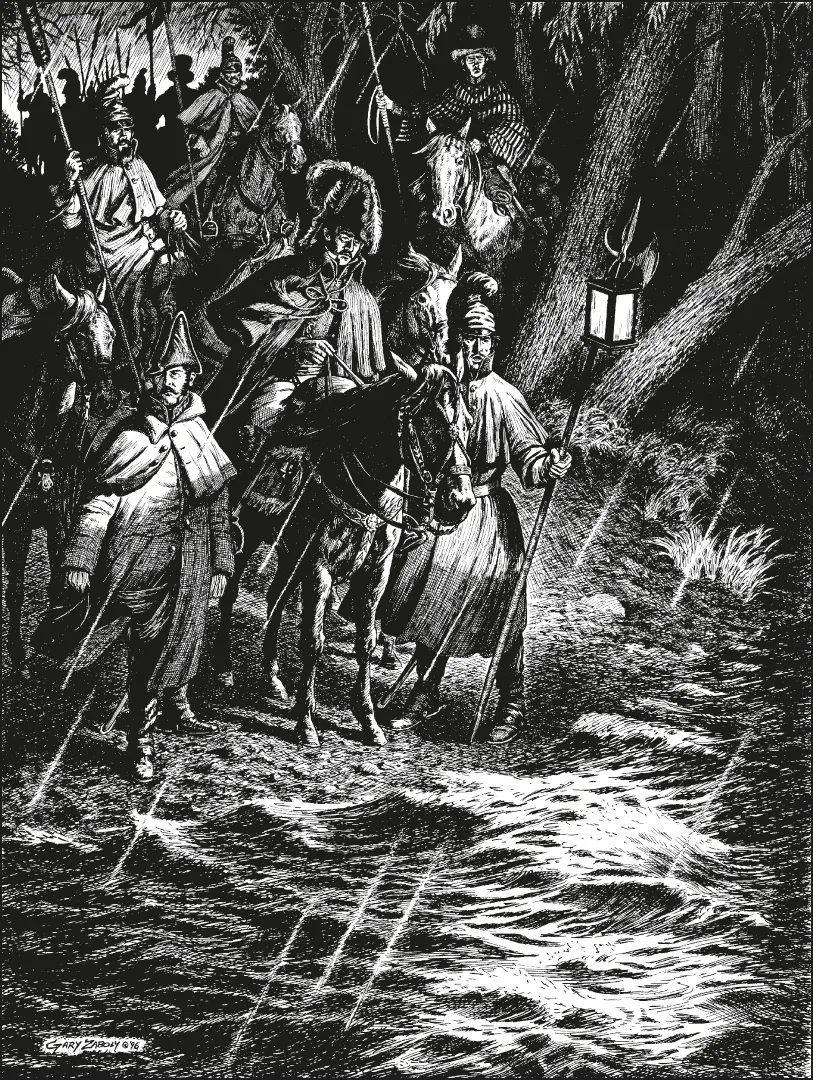

FIG. 1 MEXICAN VANGUARD AT THE MEDINA

FIG. 1 MEXICAN VANGUARD AT THE MEDINA

A little after 5:00 P.M. on February 21, 1836, Brig. Gen. Joaquin Ramírez y Sesma decides that the Medina River is too swollen with rain to ford with his detachment of sixty to one hundred dragoons of the Permanent Regiment of Dolores Cavalry. They have been ordered by General Santa Anna to surprise the unprepared Texian garrison at San Antonio. Many of the dragoons, their own mounts poor, are riding horses borrowed from Mexican infantry officers.1 They are equipped against inclement weather with helmet covers and buff-colored, caped overcoats with green standing collars.2 Most have the pennants of their lances protected with waterproof covers in the manner of Napoleonic cavalry. The subaltern at lower left has removed the plumes from his bicorne.

Sesma wears a dark blue cloak with cord.3 A green sash envelops his waist, and his bicorne sports a white feathered crest and a tricolor cockade with three loose plumes in the national colors: red, white, and green.

The sergeant to the right of Sesma holds a lantern on a halberd-tipped lance. Such lances are known to have been carried in Mexico as early as 18114 and at least into the mid-century.5

In upper middleground is one of the presidial troopers accompanying Santa Anna’s advance units. These were frontier garrison soldiers, some of them Texas-based and many of them experienced Indian fighters. They were of particular use to the main army by acting as scouts and foragers. This one does not wear the low-crowned poblano seen in Linati prints of presidials of the mid-1820s, but a black top hat derived from a painting by Lino Sanchez y Tapia made in Texas in 1828.6 His jacket also differs from the earlier depictions by sporting three rows of white metal buttons on the chest rather than one. A serape covers most of his uniform. His horse’s headstall and bit are also based on the Tapia painting.—GZ

Sutherland

Finally he [Travis] was informed secretly by a friendly Mexican, that the enemy’s cavalry had reached the León [Creek], eight miles from the city, on the previous night, and had sent a messenger to the inhabitants, informing them of that fact, and warning them to evacuate the city at early dawn, as it would be attacked the next day. He [the friendly Mexican] stated further that a messenger had arrived a day or two before and that it had been the purpose of the enemy to take the Texians by surprise, but in consequence of a heavy rain having fallen on the road, their march was impeded, and they were unable to reach the place in time. This statement seemed to substantiate the statement in the report given by [Blas] Herrera three days before, yet it wore the countenance of so many of their false rumors that it was a matter of doubt that there was any truth in it.

Colonel Travis came to me forthwith, however, and informed me of what he had learned, and wished to borrow a horse of me to send out to the Salado [Creek]6 for his caballo7 that he might start a scout through the country. As I had two [horses], of course he obtained one, when a runner was started forthwith [for the horses?]. In company with Colonel Travis and at his request, I proceeded to post a reliable man on the roof of the old church as a sentinel. We all three went up but were unable to make any discoveries. The colonel and myself returned. The sentinel r...