Chapter 1 The Road To Shiloh

The Soldiers

Few nations were as unprepared for war, least of all a civil war, as were the combatants in April 1861 when the Slavery-State Rights powder keg exploded at Fort Sumter. At the time the U.S. Army numbered about 16,000 “regulars.” The Confederacy possessed no army at all except for the few hundred U.S. Army officers who resigned their commissions and joined the South. Within months, both sides would be training and arming tens of thousands of citizen-soldiers.

Both sides built their armies via a state volunteer system, and both Presidents – Lincoln and Davis – called on their respective states to provide quotas of troops organized into companies – theoretically 100 men per company – and these companies would be combined into regiments – theoretically 10 companies per regiment.

Off to See the Elephant

For the eyeball-to-eyeball business of forming the companies, state governors relied on local politicians and community leaders to recruit volunteers in thousands of towns and villages. For young men who had never set foot outside their county, the prospect of going to war like their revered Revolutionary War forefathers was the thrill of a lifetime - a lot more exciting than milking cows or clerking at the hardware store. Tens of thousands raced to sign up in recruiting drives packed with hometown parades, bands, cheering crowds, absolutions and blessings by local clergy, and stirring speeches by town fathers. The women joined in the excitement by sewing flags and uniforms of every color and design. If their town was big enough to support a photographer, the recruits lined up to have their photo taken. The boys were embarking on a tremendous adventure “to see the elephant,” which meant seeing something wondrous – in this case, battle. None of them had ever seen a battle except maybe in a colorful painting of the Revolutionary War or the Battle of Waterloo, where war always looked glorious, and smoky.

Finally the proud companies tramped off to war through their town's streets, hopelessly out of step, past the cheering crowds of mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles and above all, the girls, while being relentlessly serenaded by local bands. The recruits, if they had weapons, were usually armed with shotguns, old muskets, various calibers of squirrel guns, and evil-looking hunting knives. Their officers were local community leaders - usually lawyers/politicians but sometimes school masters and preachers.

These companies would eventually rendezvous at large camps where things were only slightly less festive, with lots of singing, harrahing, and marching. The first order of business was to merge the companies into regiments, the regiments into brigades, the brigades into divisions, and the divisions into corps. The fancy hometown flags were packed up and shipped home; only regiments would carry flags in this war. The officers of the various companies in each regiment gathered and elected a colonel and other field officers from among their number. Few of these officers had any military experience.

It would be a massive understatement to say this recruiting system was imperfect. The North’s system was even more imperfect because the legal enlistment-term established by the Uniform Militia Act of 1792 limited the military term of volunteers to 90 days. So when Lincoln called up 75,000 volunteers after Fort Sumter, their terms had expired by the end of summer 1861. Some of these three-month volunteers reenlisted for three years, some didn’t.

But this hometown method of building armies had one major advantage: it created tremendous cohesion. Almost every soldier knew his comrades, since they were all from the same community. Each soldier's performance on the battlefield would be relayed to that soldier's family, neighbors and community, and remembered forever. And back then in America, physical cowardice was not considered a virtue.

Through the fall, winter and spring of 1861-1862 the North raised armies and funneled them to jump-off points for a southern offensive. In the western theater, that point was Cairo, Illinois where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers converge.

Militarization got off to a slightly smoother start in the South due to war-exuberance that gripped Southerners at the time; plus Confederate President Jefferson Davis had the legal ability to summon volunteers for twelve months, not three. Also, due to the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831, and John Brown’s raid and attempted slave revolt of 1859, many Southern communities had already organized local militias, convenient for fast conversion into military units.

But the lion’s share of organized regiments in the Southern states, which included most of those with military training or Mexican War experience, went to Virginia for the defense of Richmond. By the beginning of 1862, the eighth month of the Civil War, many battles had been fought but few were of consequence, except of course to the participants, with the major exception of the First Battle of Bull Run in Virginia and, to a lesser extent, the Battle of Wilson Creek in Missouri.

Both sides, while still hoping knock each other out in a short war, were girding for a long one. And what both sides didn’t yet know about conducting wars could have filled volumes.

The Kentucky Shield

Soon after war was declared, Kentucky, a critical border state, proclaimed its "neutrality," and forbade troops from either side from crossing its borders. The Federals had to respect Kentucky’s prohibition since Lincoln was determined to avoid any act that might tilt the state into the waiting arms of the South. Kentucky’s neutrality was a boon to the Confederacy since it shielded Tennessee’s long northern border without the need to station troops there.

But the South threw away its Kentucky shield when, in September 1861, Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, the commander of Confederate forces in the Mississippi Valley, took it upon himself to occupy the Mississippi River town of Columbus, Kentucky, thus violating Kentucky neutrality. Polk’s move was logical from a tactical standpoint – Columbus stood on a high bluff which dominated the river for miles. But from a strategic and political standpoint, his move was a disaster because it drove most Kentuckians straight into the arms of the Union (Kentuckians went Union four to one); worse, Tennessee’s long, nearly undefended northern border was now fair game for a Union invasion.

The Federals

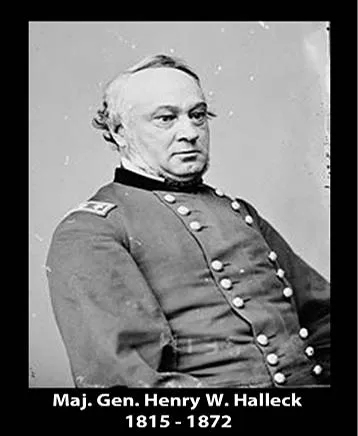

Through the winter of 1861-1862, the fiercest fighting in the western theater occurred between Union Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck in St. Louis and his Ohio rival, Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, in their competition to win overall western command. Eventually Halleck won and Buell’s army was consolidated into Halleck’s Department of Mississippi, which now included all Union forces in the Mississippi and Tennessee River valleys.

The bookish Halleck, with his sly demeanor, was a learned but plodding officer who was far more comfortable mounted on a chair in the office than on a saddle in the battlefield, particularly given his constant battle with hemorrhoids.

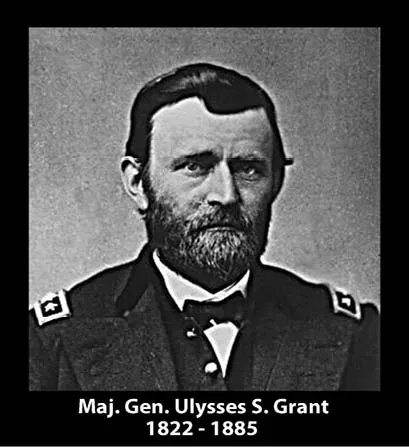

But he did have at least one aggressive subordinate – Ulysses S. Grant – a brigadier general commanding the forces in Cairo, Illinois. Just over a year earlier, Grant had been feeding his family by peddling firewood on the streets of St. Louis. He was an introvert with a rather dull personality. Quiet and ill at ease in public, he didn't smile much. He was said to be alone, even in a crowd. With the look of a failure, he was someone you might expect to find drinking alone in a tavern. He was in every way perfectly plain and ordinary except, as it would turn out, he had a healthy dose of Midwestern common sense and a logical mind, combined with two extraordinary talents: a bulldog determination and an uncanny ability to stay calm in situations that would drive most sane men hysterical.

Now, even though he had a reputation as a drunkard, he commanded thousands of men. Soon he would be commanding tens of thousands, and eventually hundreds of thousands.

In November of 1861, before Halleck assumed command, Grant was under the command of Gen. John C. Fremont, who was known as "The Pathfinder" for his conquest of Califo...