eBook - ePub

Finance in Africa

for green, smart and inclusive private sector development

European Investment Bank, European Investment Bank

This is a test

- 146 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Finance in Africa

for green, smart and inclusive private sector development

European Investment Bank, European Investment Bank

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Africa's recovery from the COVID-19 crisis will depend on private firms sustaining and creating jobs. But even previously thriving enterprises have been badly hit by the crisis. This report outlines the consequences of the health crisis in Africa, the potential cost of the recovery and the willingness of banks to support green investments as they look to the future.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Finance in Africa è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Finance in Africa di European Investment Bank, European Investment Bank in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Business e Corporate Finance. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

BusinessCategoria

Corporate Finance1

Banking in Africa: supporting a sustainable and inclusive recovery[1,2]

Introduction and context

Africa’s economies – emerging from crisis to uncertain prospects

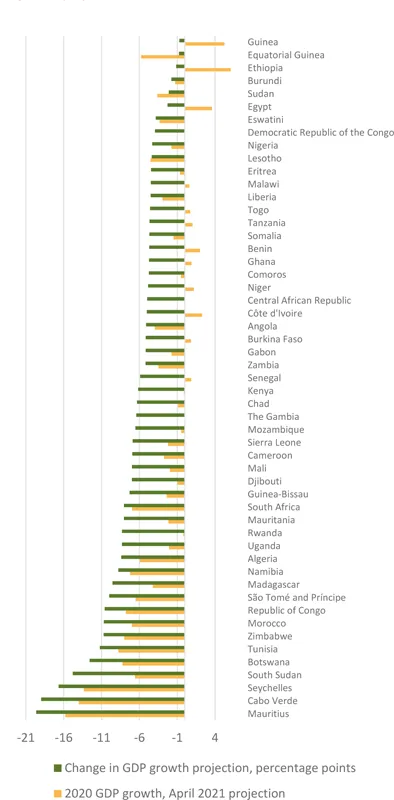

The COVID-19 crisis has had a significant human and economic impact on Africa, despite the reported virus caseload being relatively low for the continent. As of July 2021, Africa has reported fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths, relative to the population, than any other world region except the Western Pacific[3]. Nonetheless, some countries (particularly Tunisia and South Africa) have been severely hit, with seven African countries reporting death rates above the world average[4]. Moreover, as test rates in most African countries are extremely low, the extent of the health crisis may be understated. Almost all African countries have implemented measures to contain the pandemic, which has significantly reduced economic activity. The crisis has also affected international financial and commodity markets and Africa’s trading partners, with knock-on effects for African economies. Tourism, which is important for numerous African economies (particularly but not only small island states), came to an almost complete standstill during 2020, while the prices of oil, gas and other commodities plummeted early in the year. Overall, gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 2.3% on average across Africa during 2020 (IMF, 2021a), with the vast majority of countries experiencing a contraction (Figure 1). Countries highly dependent on tourism or commodity exports experienced the most severe slowdowns, along with states already grappling with severe macroeconomic challenges before the crisis (such as growth slowdowns or nascent debt crises). Furthermore, like many emerging or developing markets, African economies had fragilities at micro and macro levels that have exacerbated the impact of the crisis, despite their growth contraction being smaller in percentage terms than that of advanced economies.

Figure 1: The contraction – GDP growth in Africa, 2020 and change to growth projections, %

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2019 and April 2021 versions[5].

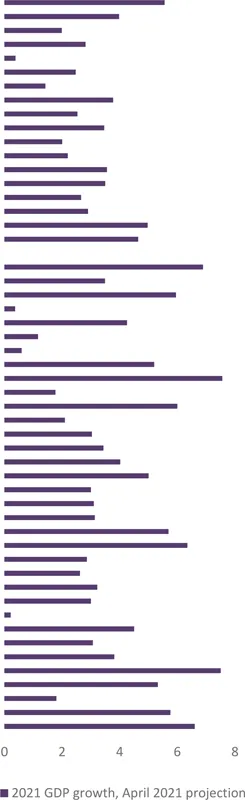

Figure 2: The recovery – projected GDP growth in Africa, 2021, %

Although the average growth contraction in Africa has been smaller than in developed regions, African firms and households are highly exposed to financial risks, with already vulnerable groups most severely affected. The small and informal enterprises and self-employed workers that form the backbone of African economies often have limited resources to withstand economic downturns. Many may find it difficult to restart activities even when conditions improve. Most low-income households lack savings to cushion the impact of lost earnings. Furthermore, few workers can rely on social safety nets or insurance, as these generally do not cover informal sector workers and, in many African countries, provide only limited benefits even to formal sector workers. Within countries, the poor and vulnerable are particularly exposed, with migrant workers, refugees and other marginalised groups likely to be worst hit. GDP per capita is not expected to recover to 2019 levels until 2024 (with risks tilted to the downside), and the crisis has reversed an expected decrease in the number of people living in poverty (IMF, 2021a). This could result in an additional 30 million people in sub-Saharan Africa living in extreme poverty by 2021, plus an additional nine million in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, relative to pre-crisis projections (World Bank, 2021a)[6]. The economic challenges facing households and the imposition of lockdown measures have exacerbated existing tensions and reduced trust in government institutions, triggering social unrest and destabilisation in several cases. Pangea-Risk, for example, reports that many African governments are facing criticism from citizens for a perceived lack of preparedness, corruption scandals, and for imposing new lockdowns too late, thus weakening confidence in the state (Pangea-Risk, 2021). Of the 39 countries on the World Bank’s harmonised list of fragile and conflict-affected situations, 20 are in Africa[7].

The fiscal response to the crisis has been muted in African states compared to advanced economies, but the increased debt burden in Africa has limited capacity to support the recovery. African countries’ fiscal stimulus packages up to mid-2020 represented about 1-2% of GDP, supplemented by monetary stimulus estimated at 2% of GDP[8]. This is close to the average for low-income developing countries worldwide reported by the IMF (around 2% of 2020 GDP over a one-year period from the start of the crisis). By contrast, emerging markets implemented a package equivalent to around 4% of GDP over the same period, while the package implemented by advanced economies was equivalent to around 16% of GDP (IMF, 2021b). This reflects the weaker capacity of African states, compared even to emerging markets, to use fiscal stimulus to support their economies during crises. Even without a large fiscal stimulus package, the average fiscal deficit across Africa rose from 5% of GDP in 2019 to over 8% in 2020 as African states sought to address the health and economic effects of the crisis while experiencing often dramatic contractions in revenues[9]. A lack of fiscal space meant that the deficit led to increased borrowing, which African states have less capacity to absorb than advanced economies. Before the pandemic, average public debt was expected to gradually decline across Africa, but average net government debt rose by 2 percentage points during 2020, reaching 61% of GDP. The rise was even steeper for sub-Saharan Africa, exceeding 6 percentage points on average. Because of this increased debt burden, countries are facing higher debt servicing costs and some have lost international market access altogether, leaving them dependent on relatively limited domestic resources and concessional funding[10]. Sixteen African countries have been downgraded by at least one ratings agency since the start of the pandemic, including one country that defaulted (Zambia)[11]. Further defaults have been forestalled, partly thanks to debt relief initiatives by the international community, but these are limited and not all countries will take up debt relief to preserve market access[12]. Even countries that retain market access are likely to face higher costs of funding. Overall, African governments are left with limited capacity to either stimulate the economy during the recovery or support much-needed investments for a resilient, sustainable and inclusive future.

The recovery is expected to be gradual, and uncertainty about economic prospects remains very high. The IMF expects average growth across Africa to recover to 4.5% in 2021 and 4.0% in 2022, with all economies apart from Comoros expanding in 2021 (IMF, 2021a). However, significant variation in growth rates is forecast (between 0.2% in the Republic of the Congo and 7.6% in Kenya during 2021; see Figure 2). More recent estimates have downgraded the growth prospects even further. For example, the World Bank’s June 2021 economic update adjusted the growth projection for sub-Saharan Africa down by 0.2 percentage points[13]. The relatively moderate projected growth rates for the medium term are below pre-crisis projections, both on average and for most countries[14]. This reflects sluggish growth prospects in most of the continent’s large economies[15]. Although the recovery in commodity prices has boosted the medium-term prospects of countries dependent on oil, gas and mining exports, vaccine rollouts have been very slow compared to developed countries[16], which raises the risk of further ...