![]()

SECTION TWO

CHANGES IN AND AFTER HERGÉ

![]()

CHAPTER FIVE

CONTINUING CLEAR LINE 1983–2013

Matthew Screech

INTRODUCTION

Clear line is a term famously coined by the Dutch artist Joost Swarte to define a graphic style that began in The Adventures of Tintin during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Clear line was further popularized by Hergé’s emulators and collaborators at Le Journal de Tintin, who became known as the Brussels school. Pierre Sterckx discerns three indispensable components to Hergé’s graphics (“Silences” 4–18). The first derives from classical realism’s authenticating tradition. Meticulously researched, closely copied pictures of familiar objects and places create the illusion that Tintin, a fictional hero, really exists. Of course Hergé’s mimetic realism, for all its detail, is selective. As Le Journal de Tintin was conservatively Roman Catholic, overt sex and violence are filtered out. Clear line conjures up an idealized reality, where angelic Tintin triumphs over evil. The second component is geometric, and it concerns how panels are organized. Hergé complies with perspective and proportion; contours are precise and clearly defined, particularly as there is no shadow; carefully arranged people and decor are rendered in continuous black lines of regular thickness; those lines enhance Hergé’s pastel colors, resulting in a pleasant luminosity. The third component disrupts the prevailing rationality with humorous, caricatural, clownish elements, which include: onomatopoeia, multicolored stars or sweat beads, and spiraling arabesques denoting movement.

Sterckx elaborates on why, despite Hergé’s apparent simplicity, nobody has recaptured his style: all of the components are essential. However, as each story unfolds, the consummate draftsman subtly shifts his emphasis from one to another. Other artists, by contrast, adopt this or that aspect of Hergé, without synthesizing all three. One example is Blake & Mortimer, by the Brussels school artist Edgar Jacobs. This sci-fi spy thriller, based in 1950s/60s England, has more shaded tones than The Adventures of Tintin, as well as more text. Jacobs’s mimetism equals (or surpasses) Hergé’s, and he shares Hergé’s geometric rigor, yet Jacobs barely engages with Hergé’s humorous component: his characters’ movements are theatrical, and their reactions are naturalistic.

Bruno Lecigne’s landmark study Les Héritiers d’Hergé examines how artists redeployed clear line up to 1983. Since then critics have largely ceased theorizing about how clear line evolved, and very little research is being done into the question, although Paul Gravett wrote two important articles: one delves into clear line’s origins; the other focuses on later developments, especially the Dutch underground. My essay makes a new contribution to the debate by extending the investigation into clear line’s evolution as far as 2013. The discussion centers on Dutch, French, and Swiss artists, who have mostly received little sustained critical attention either among Anglophones or in their countries of origin. I retain Lecigne’s and Gravett’s chronological structure, but I am less informed by Jean Baudrillard than is Lecigne, who espouses the philosopher unconditionally. Les Héritiers d’Hergé was not translated into English and never reached a wide Francophone readership; the book bristles with difficult Baudrillardian terminology, it appeared with a small publisher, and it has long been out of print. As a consequence, English, French, and Dutch speakers alike will benefit if we briefly review Les Héritiers d’Hergé as well as some Baudrillard before starting. Baudrillard is celebrated for his provocative insights into society; he is also criticized for hyperbole, unsystematic analyses, and not explaining his terms. I shall not revisit the arguments for and against him here; Mark Poster offers a résumé (1–9).

Baudrillard’s “The Order of Simulacra” influenced Lecigne (Symbolic Exchange and Death 50–86). Baudrillard contends that, over time, images ceased to have an original reference point in reality, and they evolved into pure simulacra, by which he means copies without an original. The classical period ran from the Renaissance to the modernizing Industrial Revolution. At this stage images had an unquestionable referent in reality underpinned by religion. Industrialization brought rapid change: religious practice declined, and the referent was weakened as simulacra spread by means of mechanically produced images. Today’s late capitalist era is characterized by pure simulacra, which indicate that the referent is irretrievably lost; pure simulacra pertain to no reality beyond themselves, and examples include Pop Art and graffiti. Baudrillard develops the sociocultural implications in Simulacra and Simulation. This book, published one year before Les Héritiers d’Hergé, also influenced Lecigne. Baudrillard sees simulacra as having become ubiquitous; they are proliferating through the popular mass media, and they dominate every aspect of our thinking, as examples such as the space race, advertising, exhibitions, and Disneyland testify.

Ann Miller points out that Lecigne views The Adventures of Tintin as epitomizing Baudrillard’s evolutionary process, “from the confident assumptions in the early albums that the images on the page were signs of the real until, in the final albums, the realist illusion was destroyed and the album became a pure simulacrum” (Reading 127). Lecigne argues persuasively that Hergé and Jacobs perfected classical Brussels school aesthetics. The two artists, respecting principles dating back to antiquity, imitate reality within strict rules, while amusing and instructing the public: tasteful harmony between artistic form (clear line) and ideological content (conservative Catholicism) communicates an unambiguous message exemplified by virtuous, mythological heroes. Tintin, in particular, embodies a Manichaean truth about humanity whose existence is accepted uncritically (19–20, 43–44, 155). Lecigne proceeds to demonstrate how Hergé, showing incipient modernist tendencies, gradually left mimetic realism behind, and he cultivated pure, Baudrillardian simulacra instead: The Adventures of Tintin have ever more people, places, and objects that, rather than authenticating fiction, lack any original referent in reality; the only reality lies in the pictures themselves (Lecigne 53–55). The development culminated in The Castafiore Emerald, an album set in the imaginary Château de Moulinsart and not supposedly in the real world. The Castafiore Emerald further undermines classical precepts: Tintin’s status as the mythological incarnation of virtue is weakened by a lack of worthy opponents when the villain turns out to be a magpie. Blake & Mortimer halted at the classical stage: well-researched decor authenticates exemplary exploits following a realist tradition.

Lecigne goes on to assert that the next generation were modernists because, going further than Hergé, they openly rejected classical Brussels school aesthetics. Again, Lecigne is persuasive. Clear line modernists, to varying degrees, resemble their earlier twentieth-century forbears: they stopped instructing readers with exemplary models; they refused to represent the visual more or less directly; they rebelled against preexisting notions of harmony and taste. Clear line modernism, like its predecessor, coincided with a crisis “in which myth, structure and organization, in a traditional sense, collapse” (Bradbury and McFarlane 26). Not by accident, the modernist trend emerged during the upheavals of the late 1960s/early 1970s with the Dutch underground: Joost Swarte depicts an amoral universe with no equivalent in reality (Lecigne 53–75). Clear line remained popular in the Netherlands. One later instance is Theo van den Boogaard’s Leon van Oukel, whose misadventures exacerbate clear line’s propensity for clownishness (Lecigne 91–97). We shall see that Dutch interest in clear line persists to this day.

Hergé and Jacobs were unfashionable in post–May ’68 France. Nonetheless, clear line’s impact became apparent from the mid-1970s with Jacques Tardi. His magnum opus, Les Aventures extraordinaires d’Adèle Blanc-Sec, overturns the principles governing classical Brussels school aesthetics: Adèle’s adventures, set in early-twentieth-century Paris, ironically subvert clear line artists’ graphics, as well as their right-thinking myths and ideology (Lecigne 79–81). As Tardi’s style resembles Jacobs’s, Adèle Blanc-Sec marks a new phase in simulacra proliferating: Tardi copies Jacobs, who copies Hergé; clear line is thus once removed from its original referent. Ted Benoît’s clear line thriller Berceuse électrique is closer to Swarte or later Hergé than to Tardi: familiar objects abound, but the story lacks status in any determinate reality (Lecigne 123–27).

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, a genre Lecigne defines as neoclassicism came into being (137–53). The clear line was predominantly Jacobsian thanks to Tardi. Neoclassicism adopted Tardi’s historical detail but neither his experiments nor his barbed wit: local color lends adventures credibility, although humor is rare; the Brussels school ideology having gone, sex and violence are permissible. Lecigne judges neoclassicism to be second-rate Tardi. The one exception is Swiss artist Daniel Ceppi, whose Stéphane Clément: Chroniques d’un voyageur modernized neoclassicism: Ceppi, shunning the usual retro settings, recounts a fugitive backpacker’s escapades in Turkey, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

Les Héritiers d’Hergé concludes with a hierarchy based on Baudrillard (Lecigne 155–59). If the real is conceivable only in a simulated form, then attempting to represent it accurately is futile. Consequently, neoclassicism is of the lower order: neoclassicism frustrates clear line’s potential to produce pure simulacra, by fruitlessly recycling classical realism’s authenticating strategy. Above are the modernists, who reject classical aesthetics: their simulacra, by removing the referent in reality, open up innovative possibilities for clear line. Baudrillard’s hypotheses and Lecigne’s value judgments are, by their nature, debatable. Nevertheless, Les Héritiers d’Hergé does provide a valuable starting point for our updated analysis of clear line: it is most pertinent to ask whether or not artists reference the real. What is more, as we shall see, some later artists no longer fit Lecigne’s modernist/neoclassical hierarchy. After the 1980s, innovating ceases to be contingent upon removing the referent in reality.

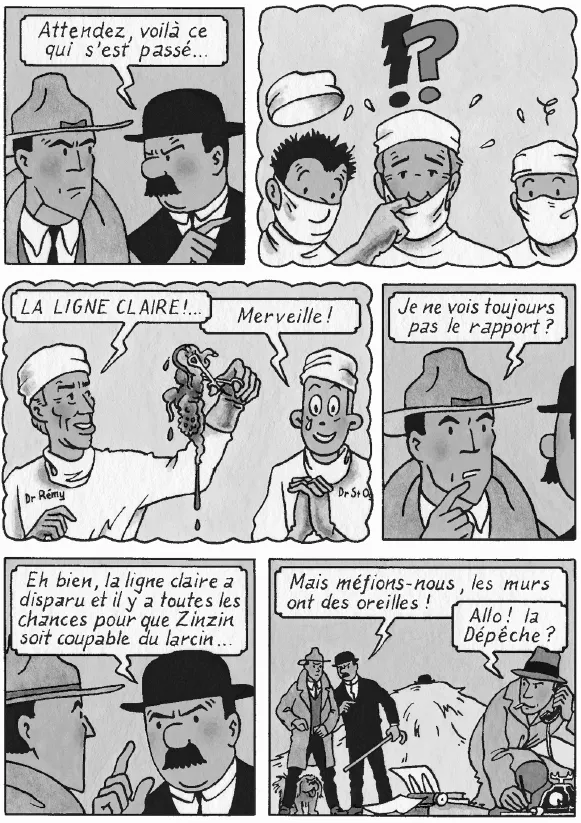

1983–1993: SIMULACRA AND NEOCLASSICISM

The year 1983 was not just when Lecigne published Les Héritiers d’Hergé. It was also, of course, the year Hergé died. The following year, a Swiss artist called Emmanuel Excoffier (aka Exem) drew a tribute titled “Le Jumeau maléfique” for the small Genevan publisher Éditions Tchang (Exem 1984, repr. Herbez 35–36). Exem’s admiration for Hergé could hardly be plainer: his pseudonym, similar to Hergé’s, inverts the first two letters of his first and last name. Ariel Herbez observes that Exem has the vivacious caricatures, hot pursuits, and relatively simple backgrounds of earlier Hergé; however, Herbez adds that Exem creates simulacra rather than imitating reality (20, 26). Moreover, Exem plays with a Baudrillardian preoccupation: if Tintin is a simulacrum (i.e., a copy of a nonexistent person), then he is reversible; Lecigne insists repeatedly on the reversibility of simulacra (43, 53, 70, 96). Exem’s take on reversibility shows how easily Tintin can be converted into his opposite. He invents Tintin’s identical twin brother, Zinzin, an antihero who embodies everything Tintin is not: Zinzin is a thief, he covets power, he has sex, and he provokes bloodshed. In a second strip, “Zinzin maître du monde,” Tintin’s autopsy (officiated over by Hergé) reveals that Tintin is neither male nor female, because his genitalia consists of clear line; the vital organ is promptly snatched away by Zinzin, to misuse for his own purposes (Exem 1985, repr. Herbez 38–44; see figure 1). Zinzin appropriating clear line intimates that clear line has become nothing less than a system of reversible simulacra; an identical point was made by Lecigne when he explained the graphic style’s transition from classicism to modernism over the previous decade (50, 155).

Some 1970s parodists exploited Tintin’s reversibility, but they simultaneously attacked his mythological standing, usually by sexualizing him (Lecigne 105). Exem does the opposite. Exem remythologizes androgynous Tintin, with a fervor not seen since the Brussels school’s classical heyday: Tintin retains his chastity, and his saintliness is accentuated by Zinzin, who would alter Hergéan clear line. At the same time, Exem reveals modernist tendencies: the Brussels school’s classical realism and its ideological underpinnings are roundly rejected; Tintin is remythologised, but as a reversible simulacrum who enjoys no reality beyond comics. Exem’s blend of classicism and modernism makes him the first artist to fit oddly within Lecigne’s concluding hierarchy.

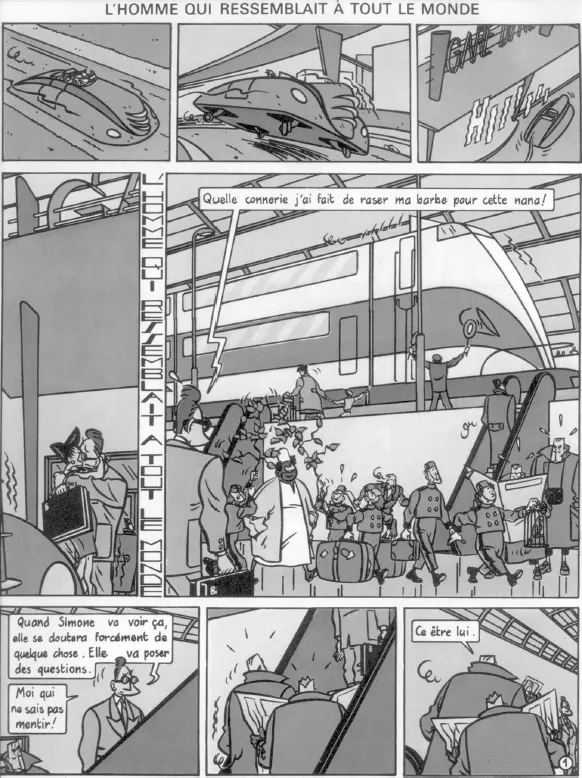

Lecigne never mentions Exem. However, other clear line artists he tips both as potentially interesting and as continuing the trend Hergé started did produce pure simulacra during the next ten years. Dinghys dinghys (1984) by Marc Barcelo and Jean-Yves Tripp recalls Tintin and the Picaros, but it has more violence and less humor. The story recounts a terrorist attack during a masked carnival at a desert oasis, where North African architecture mingles with sheer fantasy in the form of a talking mouse. En pleine guerre froide (1984), a collection of short stories by Jean-Louis Floc’h and Jean-Luc Fromental, moved clear line SF toward Swarte and Benoît: it portrays times and places that remain strangely unfamiliar, despite an abundance of recognizable objects. The album takes the approach to extremes: ultra-high-speed trains coexist alongside 1980s power suits and 1930s streamlining (see figure 2). There are also modernist Le Corbusier constructions and multipurpose spaces reminiscent of 1960s Hyperrealism. Hergéan clear line’s luminosity is intensified by yellows, greens, and oranges, not unlike Pop Art. Several stories are unbridled speculations about simulacra proliferating via the media and popular culture: Walt Disney is a robot (“En pleine guerre froide” 9–16); the hero’s likeness is reproduced in newspapers and advertisements (“Grigor Ivanov” 39–42); a waxwork museum’s owners are models of their nonexistent selves (“Beau dirigeable” 43–50). A distant planet’s decor comprises what are arguably clear line’s purest simulacra to date: abstract shapes, referring to no reality whatsoever (“Proximiscuité sur Proximol” 17–21). The Spanish SF artist Daniel Torres also experimented with clear line simulacra: Opium takes place in an imaginary city of the future.

In the case of Plagiat! (1989) by Alain Goffin, François Schuiten, and Benoît Peeters, a whole album hinges on simulating. Plagiat! has scenes set in a near future redolent of Benoît, but the graphics are closer to Jacobs. The artist hero invents “pure line,” an amalgam of clear line, Surrealism, Pop Art, and abstraction. He then exploits pure line’s reversibility by signing his own paintings in a plagiarist’s name. In so doing he usurps the plagiarist’s identity in the eyes of the media, who mistakenly believe them both to be the same person. The plagiarist takes his revenge by shooting the artist live on TV, but his motive is never believed, and the murder is attributed to a lone madman. Plagiat! ends with what purports to be a retrospective catalogue dedicated to the artist, perpetuating the media myth of the genius struck down in his prime (45–50). The catalogue authenticates erroneous facts about a fictional life. As a result, documentation no longer references reality; rather, it references what never had any reality to begin with. The only truth lies in simulating. An album titled Captivant by Yves Chaland and Luc Cornillon had produced an analogous effect ten years earlier. Lecigne remarks that Captivant is ostensibly a collection of 1950s comic strip magazines with dates, readers’ letters and competitions; and yet, the magazines referred to never existed; as with Plagiat!, the album is pure simulation (109–11).

Figure 2: © Jean-Louis Floc’h and Jean-Luc Fromental

If artists considered thus far all attest to an interest in simulacra, then Patrick Dumas’s and François Rivière’s Maître Berger evinces neoclassicism’s ongoing popularity. This detective series, set in late 1940s/1950s France, reinforces the realist component: Jacobsian clear line is transposed onto gentle landscapes and small towns in the southwestern Charentes region. Maître Berger languishes at the bottom of Lecigne’s Baudrillardian hierarchy, yet, it should not be written off as derivative recycling: the series encapsulates why clear line lends itself so well to crime fiction. As Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle notes, Tintin is sometimes surprised to learn that his world’s smooth surfaces are nothing but a facade (Hergéologie 77). Similarly, Berger discovers enmities dating back to the Nazi occupation behind the tranquil scenery.

Eric Heuvel and Martin Lodewijk’s Jenny Jones manifests Dutch ne...