![]()

1 / The History and Functions of Rubbings

RUBBINGS are ink-on-paper copies of engraved or cast inscriptions and designs on what are mostly cultural objects of metal, stone, and other firm substances. The rubbing technique originated in China, but the exact date and circumstances of the technique’s origin are less certain, mainly because of the paucity of extant documented early rubbings. Dating is also difficult because of the differing interpretations of early terms for copying, especially of stone inscriptions (stone was the first and thereafter most common material on which the Chinese used the technique). Finally, there is no precise knowledge of when paper and ink attained a quality suitable for making rubbings.

Views on the inception of the rubbing technique range from the Han to the Tang, as follows.

HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.)

Orthodox Chinese sources assign the initial application of the technique to the Han dynasty, including the Former (Western) Han (206 B.C.E.–8 C.E.) and the Later (Eastern) Han (25–220 C.E.). Conservative scholars have drawn primarily on three traditional sources: the second-century dictionary Explanation of Words and Elucidation of Characters (Shuowen jiezi); The History of the Later Han Dynasty (Hou Han shu); and Extension of the String of Pearls on the Spring and Autumn Annals (Yanfan lu).

The first of these sources, Shuowen jiezi, a dictionary by Xu Shen (d.120 C.E.?), makes no specific mention of rubbings, but some scholars single out one passage as evidence that the technique was known in the Han. Rong Geng observes that “in the preface of the Shuowen jiezi, Xu Shen states that ‘people throughout the country often found ritual vessels [dingyi] in mountain streams whose inscriptions surely were the ancient script [guwen] of early times;’ [and so] those ritual-vessel inscriptions already were collected by people in the Han.”1 Traditionalists may be correct in inferring that Han scholars had an active interest in pre-Han inscriptions, but they are on less firm ground in judging that they collected them as rubbings.

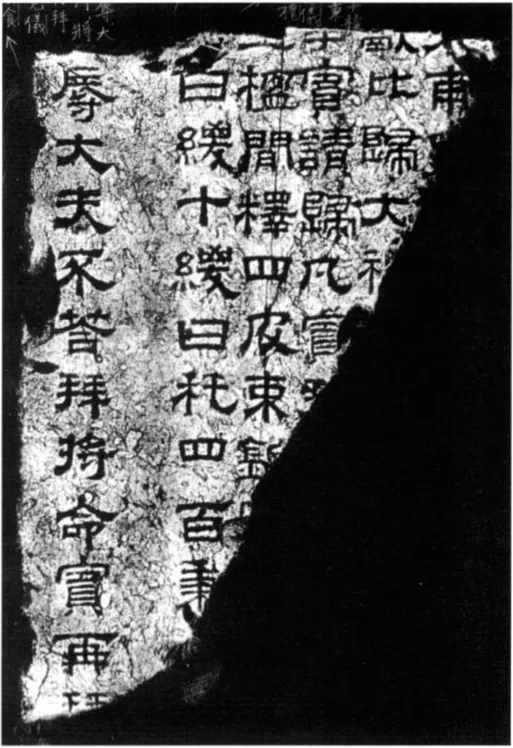

The second source is Fan Ye’s The History of the Later Han Dynasty. In the biographical section, under the entry for the eminent scholar-official and calligrapher Cai Yong (133–92 C.E.), there is an account of the great furor that accompanied the completion of the first stone engraving of the then known corpus of six Confucian classics. That historic event was initiated in the fourth year (175 C.E.) of Emperor Lingdi’s Xiping-reign period to provide an official, standard text and was completed in 183 C.E. (fig. 1.1). The History of the Later Han Dynasty credits Cai, but others contributed. Parts of the bafen script, a late form of Han clerical (li) script, are said to be in Cai’s hand:2

Lingdi gave permission for it, and [Cai] Yong then in his own hand wrote the texts for the stone tablets and had workmen engrave and erect them outside the gate of the National Academy [in Luoyang]. Thereafter, Confucianists and scholars all accepted [them] as standard. When the tablets first were erected, the vehicles of those who came to see and copy [mobxie]* them numbered more than a thousand a day.3

Conservative interpretation is that mocxie means “making rubbings.”4

The third source is Extension of the String of Pearls on the Spring and Autumn Annals, published in 1175 by Cheng Dachang. The Extension attributes to Qin-Han times the initial use of a copying technique known as “moisten with ink” (lamo).5 Cheng judges “moisten with ink” to be rubbing, but its meaning is unclear. Of incidental interest is the possible relationship of “wax ink” to “dry rubbing,” described in chapter 5.

Modern writers reject a Han date for the origin of rubbing. First, there are no extant rubbings from the Han or the following several centuries, despite more than a century of intensive archaeology and the discovery of a great volume and variety of highly perishable materials, including paper and silk. Tomorrow’s archaeology may provide rubbings from these early centuries, but till now there are none.

Second, circumstantial evidence for a Han date is unconvincing, especially as regards terminology. The chief basis for dating rubbings to the Han is the reference to the Xiping Stone Classics in The History of the Later Han. Critical opinion holds that traditionalists misinterpreted this passage, and that it means “copying by writing” rather than “reproducing by rubbing”: “Copying by writing [mobxie] is wasteful of time and energy, besides which it is easy to make mistakes. If at that time they knew about making rubbings [chuantab], they certainly would not have used mobxie, and the onlookers surely would not have been so numerous.”6 Li Shuhua suggests that perhaps one is unjustified even in translating mobxie as “make exact copies,” while Carter observes that we have no way of knowing whether the copies were exact: “At that time they still did not know about making rubbings [moataa], and … therefore the term mobxie had the meaning of imitatively to transcribe, not to make a rubbing [mobtaa].”7 Tsien concurs that moxie [mobxie] “seems to mean ‘handwriting from a copy’ rather than ‘make exact copies’ by squeezing [rubbing],” concluding that “the origin of taking impressions from inscriptions cannot be definitely traced.”8

FIG. 1.1. Fragment, Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial (Yi li), Xiping Stone Classics (183 C.E.). Author’s collection. Photograph by the author.

Terms clearly relatable to rubbing do not occur until several centuries after the Han. Wei Zheng’s History of the Sui Dynasty (Sui shu) uses chuantaa, still used for the process, to refer to rubbings from the Liang period.9 “The regular word for rubbing, t’a [tab],… did not come into use until the T’ang dynasty. The view is sometimes held that the word mo[b] … as used in the Han dynasty was the equivalent of t’a [tab] … but it is by no means certain.”10 Wang Chi-chen cites a Tang date for taa (or tuo) used synonymously with yin, a general term for printing.11 The terms tab and tac, referring to rubbings makers (tashu shou), were common in the Tang and the Song, as were da (strike) or dade (strike-obtain) for “rubbing” and daben, “a rubbing.”12

A third reason for caution in assigning a Han date to the initial use of the technique involves the origin and currency of paper. Although paper was known when the Xiping Stone Classics were cut in 175 C.E., its use seems not to have been common, and “squeezing from stone or other hard surfaces was made possible only when paper was perfected. The earlier specimens of paper of the second and third centuries, discovered in northwestern China and Chinese Turkestan, are thick and rough and do not seem suitable for taking impressions for inscriptions.”13 Reflecting the uncertainty, the same authority observes that “apparently the quality of paper during the later part of the second century C.E. must have been greatly improved, with variety of selection …[and] the cost … considerably reduced, so that … paper became a popular material for writing.”14

There is no knowledge of when paper was of a quality to make rubbings, but there is an intimate relationship between the qualities of the paper (thickness, elasticity, texture, finish) and the character of the inscription or motif being copied (size, width, depth, state of preservation). One can make an adequate copy of a large-character inscription in good state with relatively coarse paper. Rubbing fine inscriptions on oracle bones and jades demands good, thin paper, as does making a quality rubbing (jing taben).

NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN DYNASTIES (420–589 C.E.)

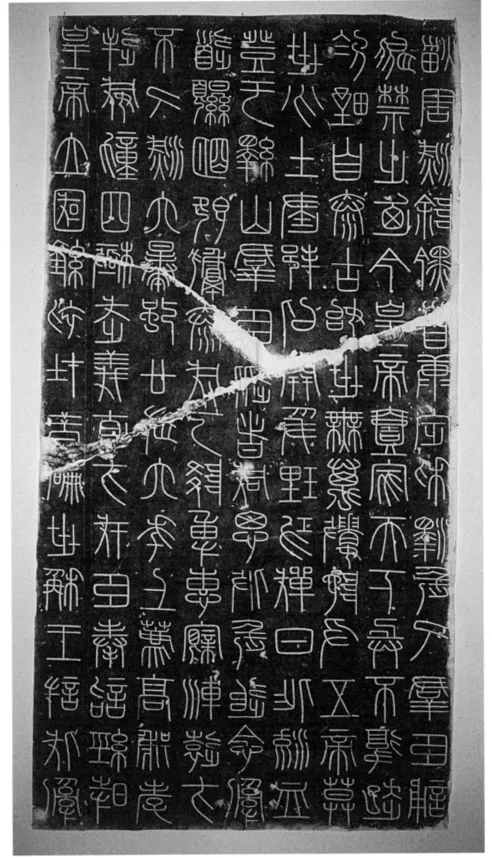

Modern writers assign the inception of the rubbing technique to the Northern and Southern dynasties. Wang Guowei states that “the rubbing technique [taamoa] originated in rubbing [taa] the Stone Classics in the Northern and Southern dynasties, and then in time was used to rub the stones cut by Qin [Shihuang].”15 Some writers place the event in the Northern (Later) Wei; others, in the Liang.

NORTHERN WEI DYNASTY (386–534 C.E.)

On the basis of literary references to an event in 450, Li Shuhua states that “in the fifth century (or even earlier) China already knew the method of rubbing [mobtab] stone tablets.”16 He draws on the vicissitudes of the Mount Yi stone (Yi Shan keshi), one of seven stones cut by Qin Shihuang following his unification of China in 221 B.C.E., as sacrifice to the gods and ancient emperors, and as validation of his conquests.17 All are recorded in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historiographer (Shiji) except the Mount Yi stone, which was listed in The History of the Later Han Dynasty.18 Save for the Langya Tai stone, these “handed down” inscriptions most likely are later recuts (plate 1; figs. 1.2–1.3).