![]()

PART 1

The Ruling House

![]()

1 Invoking Higher Authorities

Song Taizong’s Quest for Imperial Legitimacy and Its Architectural Legacy

TRACY MILLER

IN 989, TAIZONG SAW THE COMPLETION OF THE KAIBAO MONAStery Śarīra Pagoda (Kaibaosi Shelita) in the imperial capital at Kaifeng.1 Rather than employing the same craftsmen as Taizu (r. 960–976), the first emperor of the Song who made over the palaces in the manner of those at the Western Capital of Luoyang, Taizong (r. 976–997) selected Yu Hao, a famous builder from the newly acquired Wuyue kingdom, to construct his towering Buddhist edifice. This act was not a simple expression of conquest. Instead, it was one element of Taizong’s larger program to create a new identity distinct from that of his brother Taizu, who was known for his martial skills and fondness for Yellow River Valley aesthetics. By visibly demonstrating the ability to marshal substantial material and human resources toward a single endeavor, monumental constructions had long been known to bolster a new ruler’s claim to imperial authority. However, not all emperors used the same types of constructions for this purpose.

The goal of this chapter is to investigate the implications of certain building projects for the legitimacy and personal power of the first two Song emperors. Their pattern of building patronage and ritual performance suggests that much of what characterizes Song visual culture more broadly emerged from competition between these sibling emperors. By employing Yu Hao to build the monumental Kaibao Monastery Pagoda in Kaifeng, Taizong sought to establish himself as the leader of a new realm, one that celebrated the future as much as it embraced the past. Arguably the most public aspect of Taizong’s cultural patronage, the structure served not only to distinguish Taizong from his brother, but also to appropriate the new cosmopolitanism of the Yangzi Delta and its potential as a source of economic, technological, and spiritual power to enhance his own political capital. The pagoda marked a turning point away from the aesthetics of cultural legitimacy employed by rulers of earlier Chinese empires, those centered in the traditional capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang. It was more than a reliquary; it was a “modern” tower employed to herald the coming of a new age.

THE TOWERING PAGODA AT KAIBAO MONASTERY

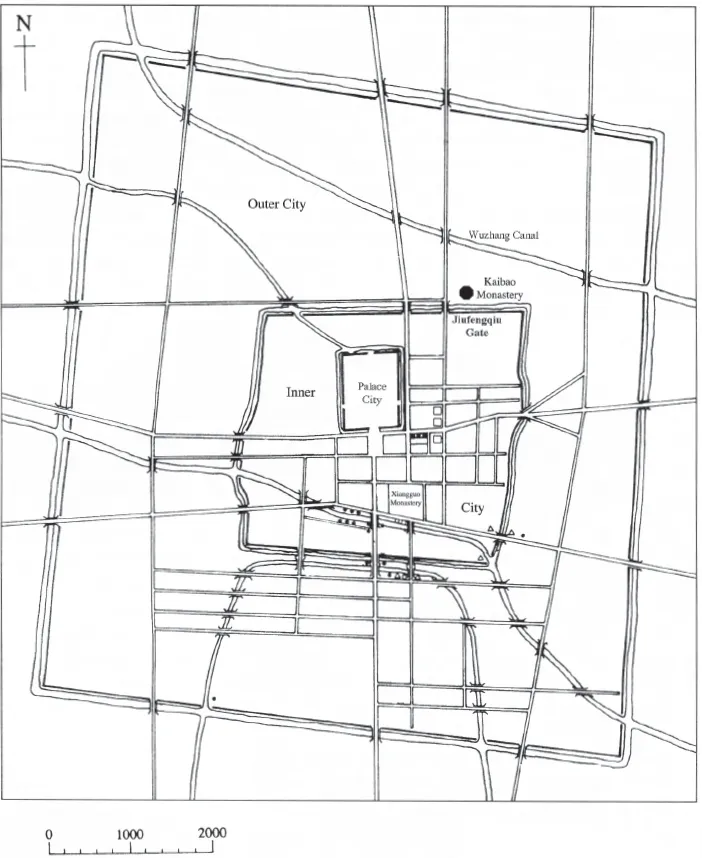

The Kaibao Monastery Pagoda is perhaps the most often discussed non-extant Buddhist pagoda in Chinese art history.2 In its prime, the building would have been something to behold. Located outside the northeast gate of the Inner City wall, or Old Fengqiu Gate (Jiu Fengqiu Men), the tower was enclosed in a separate Blessed Success Pagoda Cloister (Fusheng Tayuan), as one part of an expansive imperial Buddhist monastery named after the Kaibao reign period of Song Taizu (fig. 1.1).3 Prior to its destruction by fire in 1044, the Kaibao Monastery Pagoda was, according to Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072), the tallest in the capital and considered to be an incredible feat of architectural engineering.4 Although criticized by contemporaries as an example of excess, the same sources tell us the structure was unprecedented, “resplendent in gold and jade green” (jinbi yinghuang), and took more than eight years and hundreds of millions in cash (yiwan) to complete. According to Yang Yi (974–1020), Li Tao (1115–1184), and Zhi Pan (thirteenth century), the final structure was eleven stories tall, and all sources agree that the octagonal timber pagoda soared to 360 chi which, based on excavated Song-period carpenter’s squares, would be approximately 111.28 meters high.5 To give a sense of its height, the structure was roughly 43.97 meters taller than the extant Liao dynasty Fogong Monastery Sakyamuni Pagoda (Fogongsi Shijiata, commonly known as the Yingxian Muta, ca. 1056–95) which stands at 67.31 meters (fig. 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1. Kaifeng during the Song dynasty. Scale is in meters. Illustration based on Heng, Cities of Aristocrats and Bureaucrats, 153.

Perhaps because it was such an architectural wonder, we also know much about Yu Hao, the designer of the tower and the most renowned timber craftsman (duliaojiang) of Song China. One of the more detailed accounts of Yu Hao and his famous tower comes from the collected tales of Yang Yi, a favorite of Taizong’s who participated in the compilation of the Veritable Records of Taizong (Taizong shilu) and later coedited the Outstanding Models from the Storehouse of Literature (Cefu yuangui). Yang Yi started his court career as a precocious child who, in 984 at the age of eleven sui, was brought to the palace for a personal examination by Taizong and then retained in the Department of the Palace Library as a proofreader.6 Yang arrived at the capital shortly after the tower’s construction had begun. He would likely have had an opportunity to watch the process as both boy and tower grew to maturity. Yang wrote that Yu Hao was extremely skillful (jueqiao) and began his project by presenting a model to the court.7 Once on the job site, Yu Hao constructed each story secretly behind a curtain, carefully ensuring the stability of each before moving on to the next, so the structure could last 700 years without falling out of alignment (ci ke qibainian wu qingdong). Perhaps most famously, when questioned about the slightly higher northern side of the structure, he replied that he had taken environmental conditions into consideration: he claimed the northerly winds and damp ground (because of closeness to the Wuzhang canal) would have an effect on the building and it would, after a hundred years, become level.8

FIGURE 1.2. Śakyamuni Pagoda, Fogong Monastery, ca. 1056–1095, Yingxian, Shanxi. (Photo courtesy Scott Gilchrist.)

Yu Hao was known for more than his skillfulness, however. He was also known because he was from Hangzhou, or Qiantang, the capital of Wuyue. Taizong’s choice of Yu Hao may have helped to clarify the Wuyue origin of the relic so important to prove the authentic connection to King Aśoka (ca. 304–232 BCE), the most famous royal patron of Buddhism. The pagoda was constructed to house a smaller reliquary containing one of the nineteen “true” relics of the Buddha originally distributed to China by Aśoka. Taizong ordered this relic moved from the sacred interior (jinzhong) of its pagoda in the Wuyue capital after its ruler Qian Chu (or Qian Hongchu, r. 948–978) capitulated to the Song in 978, an event discussed below.9 It is important to note here, however, that knowledge of Wuyue architecture may have been deemed critical both to constructing a structurally sound tower of this size and to creating a spiritually effective container for the new relic.

Efficacy, both structural and spiritual, was proven in the ceremony to inter the relic after its completion. Yang Yi tells us that the emperor was carried to the temple in a palanquin to personally place the relic in the tiangong within the pagoda. A white light emitted from one corner, causing the emperor to shed tears. The pagoda, now fully charged, caused dozens of palace attendants who witnessed the miracle to decide to become monks.10 Was the structure worth the great expense of its construction purely as a symbol of political legitimacy? Or could Taizong and members of his court have believed it able to generate true spiritual power? To understand the potential of architecture to project political, cultural, and spiritual affinities it is helpful to review some examples from China’s early imperial period before turning to how this Buddhist tower’s construction contributed to the Song period shift in focus from center to coast, north to south.

ARCHITECTURE AS A TOOL FOR SPIRITUAL POWER

Large-scale building projects have long played an important role in projecting political power and legitimating claims to authority. At a minimum, monumental structures embody the ability to marshal the financial, material, and human resources necessary for their creation. Often their significance also has a substantial symbolic component, using style or magnitude to suggest alliances with, distinction from, or dominance over neighboring states and/or cultures.11 And if properly designed, at least some were believed to help actualize that power. Along with military unification and establishment of the imperial bureaucracy in premodern China, the building of highly visible structures was critical to solidifying the authority of a new regime. In the early imperial period, palaces, imperial capitals, and royal temples were the best-known building types used to display state power and acquisition of the Mandate of Heaven—the divine right to demand obedience of a newly conquered population.12 The “Zhongyong” section of the Book of Rites (Liji) describes one understanding of the purpose of rites to spirits only accessible to the emperor: “By the ceremonies of the border sacrifices (to Heaven and Earth), they served God, and by the ceremonies of the ancestral temple they sacrificed to their forefathers. If one understood the ceremonies of the border sacrifices, and the meaning of the sacrifices of the ancestral temple, it would be as easy for him to rule a state as to look into his palms.”13

Through knowledge and precise performance of the rituals at both open altars and temples, the emperor could manage the needs of the state. These rites show how emperors enlisted spirits commanding natural forces and those of the imperial ancestors to facilitate rulership through the enhanced perspective—one as easy as looking into the palm—afforded by their support.14

A very similar motivation lay behind the practice of Buddhism by both common and imperial devotees. Although the celibacy and (at least nominal) rejection of the patriline that accompanied Buddhist monastic life conflicted with indigenous cultural traditions, men and women in early medieval China left their families to join monastic communities in part because Buddhism promised the aspirant the potential to “harness the powers of the spirit world.”15 Using the imperial purse, emperors were able to display their own access to that power by building ever-taller Buddhist towers.16 For example, according to the History of the Southern Dynasties (Nan shi), in 472 Emperor Ming of the Liu-Song dynasty (r. 465–472), another “Song Taizong,” set out to build a taller pagoda than the seven-story one constructed by his older half-brother, the former Emperor Xiaowu (r. 454–464).17 Perhaps because of structural difficulties the planned ten-story pagoda in the new Xianggong Monastery would not stand, so instead he constructed two of five stories.18 Emperor Ming may also have been competing with the rival Northern Wei. In 467 Northern Wei Xianwendi (r. 465–471) constructed a seven-story pagoda at the Yongning Monastery in his capital...