![]()

1

Malice and Misunderstanding

‘My husband’s left-handed too.’ The young woman sounded worried. ‘Is he going to die young?’ I couldn’t help laughing; here we go again. The story that the average left-hander dies an untimely death has been around for decades. It’s a dark fairy tale that’s proven tenacious for two reasons. Every once in a while a scientist comes along who’s happy to breathe fresh life into it simply for the sake of causing a sensation, but more important, perhaps, is the eagerness with which the vast majority of right-handed people embrace the story every time it crops up. What could be nicer than a good safe shudder? Whether or not it’s true isn’t really the point. It’s mainly a matter of guilt-free gloating.

The ease with which such stories circulate on the global rumour mill suggests that people don’t really believe them. The version most commonly heard is that left-handers die an average of nine years sooner, and that by about the age of forty most have disappeared. Were that truly the case, then left-handedness would be an extremely grave affliction, a scourge claiming a huge number of young lives – the kind of illness people talk about in veiled terms, preferably in acronyms.

‘Have you heard? Caroline’s got LH!’

‘What? Her too?’

‘Yes. You didn’t hear this from me, but . . .’

‘Gee . . . That family sure has it hard.’

This is not the sort of thing people say.

It all started in 1992, when a Canadian professor of psychology by the name of Stanley Coren published a book in which, based on his own research, he drew attention to the horrifying fact that left-handed people have lifespans nine years shorter than average. He called it The Left-Hander Syndrome. There’s no denying that Coren had a feeling for drama; he made rather a name for himself with his book and it

earned him a tidy fortune. Then people simply got on with their lives. No politicians asked questions in the House; no specialists appeared in the media to inform the public. We didn’t even see any worried left-handers forming action groups, or fearful parents-to-be demanding early pre natal testing for this fatal disorder. Nobody pressed for further research. Nowhere in the world was there even a well-meaning government information campaign. Speculation about left-handed mortality was and remains public entertainment – which is not something real illnesses are.

Coren’s book fitted a pattern that often emerges when left-handedness makes news: something grabs our attention, but it’s never more than a flash in the pan and left-handers themselves usually decline to comment. That’s another thing right-handed people always seem to overlook. In 1998 Australian biologist and journalist Geoff Burchfield asked the psychologist Michael Corballis in an interview: ‘Why do you think the subject of handedness triggers such strong responses in people, especially lefties?’ Corballis began in all seriousness to articulate a detailed answer, but he soon got bogged down in meaningless platitudes. Not that Corballis is stupid, far from it, but the question was as natural as it was misconceived. The unconventional preference exhibited by left-handed people, whom Burchfield rather dismissively refers to as ‘lefties’, is in reality something that astonishes and preoccupies right-handers. They regard the left-handers they come across from time to time as peculiar – and indeed intriguing and faintly creepy – whereas for left-handed people it’s the most normal thing in the world. They don’t see themselves and their like as in any way odd, and they are entirely used to living in a right-handed world. From an early age they have grown accustomed to the strange fascination their aberrant hand preference engenders in right-handed people.

This is a pity, really, because although right-handers get thoroughly het up about the problems they perceive to exist while left-handers merely shrug, all sorts of real puzzles remain. Along with language and cooking, the fact that the vast majority of human beings have a distinct preference for the right hand is one of relatively few characteristics that are unique to our species. Preference for one hand or paw over the other is not unusual in itself – in fact it can be found in a wide range of animals, even in mice – but the uneven distribution of left- and right- handedness is a different matter. Only one in ten people regard them selves as left-handed, whereas among animals it seems that a roughly equal number favour the left paw as favour the right.

No one can yet say with any certainty just how it comes about that one person is right-handed and another left-handed. Equally puzzling are the reasons why left-handedness arose in the first place. It must have happened a very long time ago, because another puzzle is why down through the centuries, all over the world, there has always been a stable left-handed minority of around ten per cent. That’s not all. Hand preference reflects a deeper, all-pervasive quality of human beings, namely the fact that each cerebral hemisphere has its own distinct functions, yet in most left-handed people the layout of the brain seems to differ little if at all from that of right-handed people.

As if all this wasn’t confusing enough, the concepts ‘left’ and ‘right’ are problematic in themselves. We find it hard to learn which is which, and even in adulthood we can quite easily mistake one for the other. Driving instructors are all too well aware of the possibility that a nervous pupil will yank the steering wheel in the wrong direction. Never theless, there are innumerable ways in which the distinction between left and right determines how we order, experience and comprehend the world. Photographs, drawings and paintings comply with implicit laws of orientation, as do films and comic strips.

Despite how successful some left-handers are, and how inconspicuous most remain, throughout history left-handedness has been associated with clumsiness and with unpleasant traits such as untrustworthiness and insincerity. The Latin word for left, sinister, has all kinds of dark, dismal and ominous connotations that have come into everyone of the many languages related to Latin. Science has thrown its weight into the ring at regular intervals. At the end of the nineteenth century infamous skull-measurer Cesare Lombroso had no hesitation in saying that left-handedness was a sign of a criminal personality, and in the mid-twentieth century prominent American psychoanalyst Abram Blau announced that left-handedness was tantamount to ‘infantile negativism’, the equivalent of a refusal to eat everything on your plate. Neither of these eminent gentlemen had the slightest evidence for their harsh judgements, but they weren’t going to let that spoil their fun.

The actions and attitudes of Coren and his ilk demonstrate that as far as rushing to conclusions goes, little has changed. Left-handedness was and is associated with maladies of all kinds, including mental retardation, alcoholism, asthma, hay fever, homosexuality, cancer, diabetes, insomnia, suicidal urges and criminality. In most cases there’s a complete absence of solid evidence for any such association, although it is true that groups of people with minor ailments, disabilities or stains on their

character generally include more left-handers than average, whether they be hay-fever sufferers, breast cancer patients or prison inmates. But higher than average percentages of left-handers can also be found in art colleges and architecture schools, and among the highly gifted. Then again, it turns out that within randomly composed groups of people, no differentiation based on character traits or failings has ever been found to coincide with a division into left-handed and right-handed.

|

The notorious Italian skull-measurer Cesare Lombroso, who eventually also came to believe in ghosts. |

The puzzles and paradoxes continue to stack up. There are plenty of indications that left-handed people are entirely normal, except in their hand preference, yet the fuss that’s made even today about writing with the left hand implies otherwise. It’s the subject of endless phi l o so -phizing and theorizing and often described as contrary to nature. Much is made of the ‘serious problems’ faced by Left-handed six-year-olds who are called upon to ‘imitate right-handed writing using their left hands’, as Dutch handwriting guru A. van Engen puts it. Oddly, despite all this concern, teacher training colleges fail to pay serious attention to left-handedness even today. left-handed six-year-olds generally have to find out for themselves how to master handwriting – the most

difficult skill taught in primary school – based on a model that shows them the reverse of what they are trying to do. Most manage it so successfully, despite all the problems they’re presumed to encounter, that in no time at all they can write as well and as quickly as their right-handed classmates.

Of all the many paradoxes, this one is right under our noses, since what could be more easily observable than a child writing at a classroom desk? Unless you believe in miracles, only one conclusion is possible: the image we have of left-handedness is based only to a small extent on the actual behaviour of left-handed people. Our attitudes are derived from other magical, mythical, traditional assumptions about left and right, which must be deeply rooted in our habits of thought. To unravel the puzzle of left-handedness we will have to start by examining these culturally determined assumptions. To be precise, we must return to the eve of the twentieth century in the Carrer dels Escudellers Blancs in Barcelona, to the studio of a young hothead called Pablo Picasso.

![]()

2

The Left-handed Picador

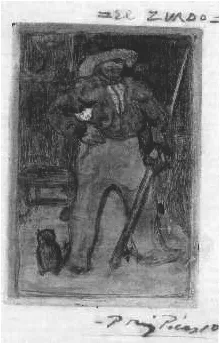

In 1899 Pablo Picasso, at eighteen already a reasonably successful up-and-coming artist, tried his hand at copper-plate engraving for the first time. He created a standing portrait of a picador, the man at a bullfight who rides around on horseback and goads the bull with a lance. The result was a disappointment in every respect, but most of all because it seemed the lance had unintentionally been placed in the picador’s left hand. Of course Picasso had engraved an appropriately right-handed picador, but his inexperience was such that he hadn’t taken account of the fact that an etching is always a mirror image of the original. He cleverly made a virtue of necessity by inscribing in wild lettering above the final result El Zurdo, the left-handed man. His honour was spared, but it was another five years before Picasso ventured to make another copper-plate engraving.

Picasso’s sense of disappointment shows how deeply ingrained is the distinction between left and right; how attached we are to getting things the right way around; how eager we all are, unconventional artists included, to conform to the norm: right-handedness.

The importance of choosing the right side in the most literal sense was demonstrated by the threats aimed at the world community, over the heads of Congress, by us president George W. Bush on 20 September 2001, just a week after the attack of 11 September 2001 that destroyed the World Trade Center in New York, with almost 3,000 deaths as a direct consequence. ‘Every nation,’ he said, ‘in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.’ On 6 November that same year, before preparations began for the invasion of Iraq – which he unleashed in March 2003 in alliance with what became known as the ‘coalition of the willing’ – Bush once again made clear just how simple a situation this was: ‘Over time it’s going to be important for nations to know they will be held accountable for inactivity. You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terror.’

| Pablo Picasso, El Zurdo, 1899. | |

Bush was the target of much justified criticism for his black-and-white vision of world politics. Anyone who kept a cool head for a moment and gave the matter some thought understood that there were all kinds of reasons why a country might decline to join Bush’s punishment expedition without necessarily harbouring any sympathy for the enemies of America, but the president, in his intellectual simplicity, provided a clear example of how people generally tend to think: in black and white. A whole arsenal of sayings underlines the point: the best of both worlds, it’s a two-way street, boom or bust, stand or fall, do or die. People are all too keen to make such distinctions as clear-cut and absolute as possible. Black-and-white clarity gives us more confidence, a greater feeling of having a grip on reality, than the grey tones of accuracy and nuance.

The US president was hardly the first leader to express himself in this way. For all his lack of charisma and rhetorical talent, Bush’s oversimplified statements placed him in a long, motley line of demagogues that goes back at least to Alcibiades of Athens in around 450 bc. He understood perfectly well, as did more recent historical figures such as French revolutionaries Danton and Marat, Lenin, Hitler and Mussolini, and indeed the entire gamut of present-day populist strongmen, that playing the crowd is all about polarization, the distilling of complicated issues into a simple antithesis. History is full of variations on the theme of ‘we’re in the right so they’re in the wrong’: we proletarians are honest, poor and oppressed, so every non-proletarian is an lackey of deceitful, filthy rich and oppressive capitalism; we Westerners love freedom, therefore the Communists tried to crush us. Similarly, most religions, especially the great monotheisms, keep their flocks united by telling them they’ve been chosen by the one true God and everyone else is doomed, or at least inferior. This is as true of Judaism as it is of Islam. Even Christianity, which has made a doctrine out of charity and mercy, has its Day of Judgment when the sheep and goats will be separated for all eternity.

Just how naturally polarization comes to us was illustrated by the witch-hunt against people alleged to have leftist sympathies in the United States of the 1950s. The episode is known as McCarthyism, but Senator Joseph McCarthy was in reality no more than a willing camp follower who managed to profit from a fear of Communism that had been growing steadily since the Second World War. Stalin’s Soviet Union had demonstrated its military might during that war and, mindful of the revolutionary Bolshevik rhetoric of the 1920s and ’30s, America was terrified of a Communist coup, even invasion. People started to see spies everywhere and in 1947 the us government initiated so-called loyalty reviews. Congress, not wanting to be left behind, set up its own commission to track down disloyal elements. Its most zealous member was a young, ambitious politician called Richard M. Nixon who many years later, as US president, would be brought down by his mistrust of others. It was called the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Note that Congress did not choose to talk of ‘anti-American’ or ‘pro-Communist’ activities. This is the most primitive and at the same time the ultimate form of black-and-white thinking: put ‘un-’ in front of your ideal and you know what it is you need to combat.

All this suggests that human beings are simply not cut out to handle nuances, since our way of thinking is based on dualism and dichotomy. Perhaps our approach has to do with the fact that there are two sexes, or maybe it arises from the distinction between the self and the rest of the world. It may have its origins in something else entirely, but the fact is that we start out by attempting to reduce any complex matter to a distinction that lies within a single dimension, imaginable as a line. We then pick a criterion and use it to chop that line in two. Every phenomenon and every property of nature is dealt with in this way: vertical length is divided into tall and short; bulk into thick and thin; time into early and late. It’s no different with man-made concepts that don’t exist in the natural world. Things are good or bad, beautiful or ugly, pleasant or unpleasant, true or false.

Triality is unknown. There’s no obvious concept of the same order to set beside true and false, or high and low. Even dealing with two dimensions at the same time, such as breadth and depth, is too much for our simple brains. What do we mean by a balcony that’s a metre and a half wide? It could be a robust structure projecting a generous metre and a half out from the wall, or a measly strip of decking attached to just a metre and a half of the facade. We learn to cope with ambiguities like this, but we always have to give them a moment’s conscious thought and we regularly make mistakes, which estate agents are happy to repeat, or indeed exploit.

Of course we wouldn’t get far if we were capable only of thinking in crude dichotomies, but we can refine our world view considerably by dividing one of two parts into two again. For example, once we’ve made a distinction between edible and non-edible things, we can split the first category into ‘tasty’ and ‘foul’. Division is a recursive process; you can go on bifurcating the result time and again. Fortunately this means that a primitive sp...