eBook - ePub

Quantitative Sensory Analysis

Psychophysics, Models and Intelligent Design

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sensory evaluation is a scientific discipline used to evoke, measure, analyse and interpret responses to products perceived through the senses of sight, smell, touch, taste and hearing. It is used to reveal insights into the way in which sensory properties drive consumer acceptance and behaviour, and to design products that best deliver what the consumer wants. It is also used at a more fundamental level to provide a wider understanding of the mechanisms involved in sensory perception and consumer behaviour.

Quantitative Sensory Analysis is an in-depth and unique treatment of the quantitative basis of sensory testing, enabling scientists in the food, cosmetics and personal care product industries to gain objective insights into consumer preference data – vital for informed new product development.

Written by a globally-recognised learer in the field, this book is suitable for industrial sensory evaluation practitioners, sensory scientists, advanced undergraduate and graduate students in sensory evaluation and sensometricians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Quantitative Sensory Analysis by Harry T. Lawless in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Psychophysics I: Introduction and Thresholds

1.1 Introduction and Terminology

1.2 Absolute Sensitivity

1.3 Methods for Measuring Absolute Thresholds

1.4 Differential Sensitivity

1.5 A Look Ahead: Fechner’s Contribution

Appendix 1.A: Relationship of Proportions, Areas Under the Normal Distribution, and Z-Scores

Appendix 1.B: Worked Example: Fitting a Logistic Function to Threshold Data

References

PORTIA:That light we see is burning in my hall

How far that little candle throws its beams.

So shines a good deed in a naughty world.

How far that little candle throws its beams.

So shines a good deed in a naughty world.

NERISSA: When the moon shone we did not see the candle.

PORTIA:So doth the greater glory dim the less.

A substitute shines brightly as a king

Unto the king be by and then his state

Empties itself as doth an inland brook

Into the main of waters.

The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1.

A substitute shines brightly as a king

Unto the king be by and then his state

Empties itself as doth an inland brook

Into the main of waters.

The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1.

1.1 Introduction and Terminology

Psychophysics is the study of the relationship between energy in the environment and the response of the senses to that energy. This idea is exactly parallel to the concerns of sensory evaluation – how we can measure peoples’ responses to foods or other consumer products. So in many ways, sensory evaluation methods draw heavily from their historical precedents in psychophysics. In this chapter we will begin to look at various psychophysical methods and theories. The methods have close resemblance to many of the procedures now used in sensory testing of products.

Psychophysics was a term coined by the scientist and philosopher Gustav Theodor Fechner. The critical event in the birth of this branch of psychology was the publication by Fechner in 1860 of a little book, Elemente der Psychophysik, that described all the psychophysical methods that had been used in studying the physiology and limits of sensory function (Stevens, 1971). Psychophysical methods can be roughly classified into four categories having to do with:

- absolute thresholds,

- difference thresholds,

- scaling sensation above threshold, and

- tradeoff relationships.

A variety of methods have been used to assess absolute thresholds. An absolute threshold is the minimum energy that is detectable by the observer. These methods are a major focus of this chapter. Difference thresholds are the minimum amount of change in energy that are necessary for an observer to detect that something has changed. Scaling methods encompass a variety of techniques used to directly quantify the input–output functions (of energy into sensations/responses), usually for the dynamic properties of a sensory system above the absolute threshold. Methods of adjustment give control of the stimulus to the observer, rather than to the experimenter. They are most often used to measure tradeoff functions. An example would be the tradeoff between the duration of a brief flash of light and its photometric intensity (its light energy). The observer adjusts one or the other of the two variables to produce a constant sensation intensity. Thus, the tradeoff function tells us about the ability of the eyes to integrate the energy of very brief stimuli over time. Similar tradeoff functions can be studied for the ability of the auditory system to integrate the duration and sound pressure of a very brief tone in order to product a sensation of constant loudness.

Parallels to sensory evaluation are obvious. Flavor chemists measure absolute thresholds to determine the biological potency of a particular sweetener or the potential impact of an aromatic flavor compound. Note that the threshold in this application becomes an inverse measure of the biological activity of the stimulus – the lower the threshold, the more potent the substance. In everyday sensory evaluation, difference testing is extremely common. Small changes may be made to a product, for example due to an ingredient reduction, cost savings, nutritional improvement, a packaging change, and so forth. The producer usually wants to know whether such a change is detectable or not. Scaling is the application of numbers to reflect the perceived intensity of a sensation, and is then related to the stimulus or product causing that sensation. Scaling is an integral part of descriptive analysis methods. Descriptive analysis scales are based on a psychophysical model and the assumption that panelists can track changes in the product and respond in a quantitative fashion accordingly.

The differences between psychophysics and sensory evaluation are primarily in the focus. Psychophysics focuses on the response of the observer to carefully controlled and systematically varied stimuli. Sensory evaluation also generates responses, but the goal is to learn something about the product under study. Psychophysical stimuli tend to be simple (lights or tones or salt solutions) and usually the stimulus is varied in only one physical attribute at a time (such as molar concentration of salt in a taste perception study). Often, the resulting change is also unidimensional (such as salty taste). Products, of course, are multidimensional, and changing one ingredient or aspect is bound to have multiple sensory consequences, some of which are hard to predict. Thus, the responses of a descriptive analysis panel, for example, often include multiple attributes. However, the stimulus–response event is necessarily an interaction of a human’s sensory systems with the physical environment (i.e., the product or stimulus), and so psychophysics and sensory evaluation are essentially studying the same phenomena.

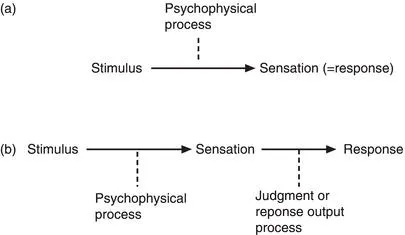

Figure 1.1 Stimulus response models in psychophysics. A classical model has it that the stimulus causes a sensation which is directly translated into an accurate response. A more modern model recognizes that there can be decision processes and human judgment involved in translating the sensation in a response (a data point) and, thus, there are at least two stages and two processes to study.

The reader should be careful not to confuse the stimulus with the sensation or response. This dichotomy is critical to understanding sensory function: an odor does not cause a smell sensation, but an odorant does. Thus, an odor is an experience and an odorant is a stimulus. Human observers or panelists do not measure sugar concentrations. They report their sweetness experiences. We often get into trouble when we confuse the response with the stimulus or vice versa. For example, people often speak of a sweetener being “200 times as sweet as sucrose” when this was never actually measured. It is probably impossible for anything to be 200 times as intense as something else in the sense of taste – the perceptual range is just not that large. What was actually measured was that, at an iso-sweet level (such as the threshold), it took a concentration 200 times higher to get the same impact from sucrose (or 1/200th for the intensive sweetener in question). But this is awkward to convey, so the industry as adopted the “X times sweeter than Y” convention.

The reader should also be careful to distinguish between the subjective experience, or sensation itself, and the response of the observer or panelist. One does not directly translate into the other. Often, the response is modified by the observer even though the same sensation may be generated. An example is how a stimulus is judged in different contexts. So there really are at least two processes at work here: the psychophysical event that translates energy into sensation (the subjective and private experience) and then the judgment or decision process, which translates that experience into a response. This second process was ignored by some psychophysical researchers, who assumed that the response was always an accurate translation of the experience. Figure 1.1 shows the two schema.

The rest of this chapter will look at various classical psychophysical methods, and how they are used to study absolute and difference thresholds. Some early psychophysical theory, and its modern variations, will also be discussed. A complete review of classical psychophysics can be found in Psychophysics, The Fundamentals (Gescheider, 1997).

1.2 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- 1 Psychophysics I: Introduction and Thresholds

- 2 Psychophysics II: Scaling and Psychophysical Functions

- 3 Basics of Signal Detection Theory

- 4 Thurstonian Models for Discrimination and Preference

- 5 Progress in Discrimination Testing

- 6 Similarity and Equivalence Testing

- 7 Progress in Scaling

- 8 Progress in Affective Testing: Preference/Choice and Hedonic Scaling

- 9 Using Subjects as Their Own Controls

- 10 Frequency Counts and Check-All-That-Apply (CATA)

- 11 Time–Intensity Modeling

- 12 Product Stability and Shelf-Life Measurement

- 13 Product Optimization, Just-About-Right (JAR) Scales, and Ideal Profiling

- 14 Perceptual Mapping, Multivariate Tools, and Graph Theory

- 15 Segmentation

- 16 An Introduction to Bayesian Analysis

- Appendix A: Overview of Sensory Evaluation

- Appendix B: Overview of Experimental Design

- Appendix C: Glossary

- Index