eBook - ePub

The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families

About this book

Written by an international team of experts, this comprehensive volume investigates modern-day family relationships, partnering, and parenting set against a backdrop of rapid social, economic, cultural, and technological change.

- Covers a broad range of topics, including social inequality, parenting practices, children's work, changing patterns of citizenship, multi-cultural families, and changes in welfare state protection for families

- Includes many European, North American and Asian examples written by a team of experts from across five continents

- Features coverage of previously neglected groups, including immigrant and transnational families as well as families of gays and lesbians

- Demonstrates how studying social change in families is fundamental for understanding the transformations in individual and social life across the globe

- Extensively reworked from the original Companion published over a decade ago: three-quarters of the material is completely new, and the remainder has been comprehensively updated

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families by Judith Treas, Jacqueline Scott, Martin Richards, Judith Treas,Jacqueline Scott,Martin Richards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Ehe- & Familiensoziologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Global Perspectives on Families

1

Family Systems of the World: Are They Converging?

Göran Therborn

Times of Change and Family Patterns

Two things, only, are certain about the future of the family. First, the family pattern will look different in different parts of the world, and the future will offer a world stage of varying family plays. Second, the future will not be like the past. The second point has an important corollary, which needs to be underlined. Times of change are seldom aware of their own proper significance. Interpreters of the present have a strong tendency either to underestimate (even to deny) what is going on or to exaggerate it (as a new era), caught up as they are in conflicting whirls of social processes and in a competitive race for attention. In the case of the family, exaggeration is the name of the game in public debate. The “End of the Family” contest is mainly between the positivists, hailing a triumph of “individualization” and the advent of “pure relationships,” and the negativists, lamenting the dissolution of society, population decline, and the coming of an old-age ice age. To understand your own time of change, you need a strong dose of historical knowledge and a self-critical distance of reflectiveness.

On the basis of my research, then, I would like to present here two conclusions.

First, there are different family systems in the world today, and they are, on the whole, not converging and in some respects rather diverging; they will also characterize the world in the foreseeable future. Second, the recent changes in the Western European or American family must be comprehended with a longer time perspective than that of the standardized industrial family between the Depressions of the 1930s and the 1970s. The great world religions and the cultural history of civilizations provide us with a world map of major family systems, internally subdivisible and still very diverse but nevertheless discernible patterns of a manageable number.

Families in the global world, what do they look like in this new awareness of the intensive interconnectedness of the planet indicated by the word “global”? What meaningful world patterns are there, making sense of the infinite individual variations? Are family patterns and behavior becoming more similar across the globe? How do families connect in today’s world? Are families losing or gaining social importance in the early twenty-first century?

Family typologies have been developed mainly by anthropologists and historical demographers with a focus on premodern, preindustrial societies and their rules of descent and inheritance, of prohibited and preferred partners of marriage, and of intergenerational rules of residence (cf. the recent magisterial overview by Todd, 2011, chapter 1). For purposes of modern and contemporary understanding, another approach may be more practical. With a searchlight on power relations, between generations and between spouses, and regulations and practices of sexuality, marital and nonmarital, we may try to discern a few large geocultural family areas of the world. Then, we can find at least seven such family systems, most of them with ancient roots, albeit historically changing in their processes of evolving reproduction. Each of them contains not only a myriad of individual variants but also distinguishable subsystems.

The World’s Seven Major Family Systems and Their Twentieth-Century Mutations

For brevity’s sake, I shall talk about “family systems,” but what I have in mind might be more adequately rendered as family–sex–gender–generation systems. A family is a product of sexuality, and one of its modes of functioning is regulating who may or may not have sex with whom. Historically, if not by necessity or future, the family is at the very center of male–female social gendering, of husband and wife, mother and father, daughter and son, and sister and brother. Thirdly, the family sets the stage of intergenerational relations, of actual fertility, and of rights and obligations of socialization, support, and inheritance. The brief overview in this chapter derives from a book-length and fully referenced study (Therborn, 2004).

- The Christian–European family, exported also to European settlements overseas and therefore also known as the “Western” family, was historically distinctive, because of its monogamy norm and of its insistence, by the Catholic Church above all, on the right to free choice of marital partner while also legitimizing nonmarriage. In Western Europe, one of the distinguishing features, transported overseas, was the norm of neolocality, transported overseas, with new couples forming their own households. Also, descent and inheritance were bilateral, with the female lineage as important as the male, with some notable exceptions, like the British aristocracy.

Social gendering was basically asymmetrical, patriarchal, and masculinist, like in most parts of the world, but its patriarchal gendering was uniquely fragile, among all major family systems. Freedom to marry, or not, monogamy, neolocality, and bilateral descent and inheritance (even if unequal), each and all gave Western European women a much stronger hand than their sisters elsewhere.

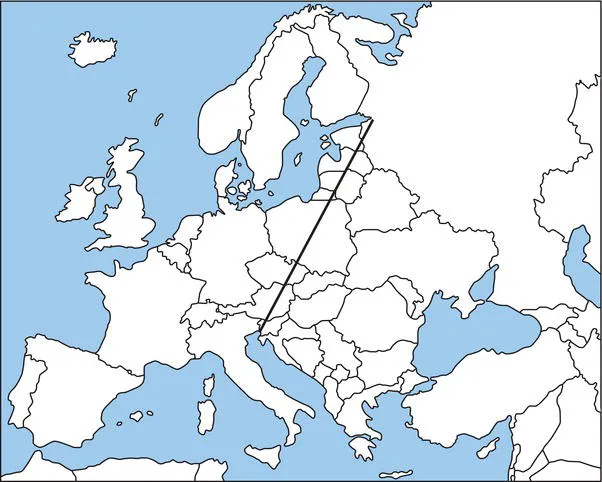

Among internal European variations, the most noteworthy historical one, very much in evidence at the beginning of the past century, was an East–West divide running from Trieste to Saint Petersburg (Hajnal, 1953) and traceable back to the frontiers of early medieval Germanic settlements (Kaser, 2000, see Figure 1.1). With nonnegligible simplification – overriding significant exceptions in Latin Europe – the line divided a Western variant of a norm of neolocality or household headship change upon marriage, late marriages, and a sizeable proportion, >10%, of women never marrying, from an Eastern one of frequent patrilineal descent (in Russia and the Balkans), patrilocality, a female mean age at first marriage 4–7 years lower, and almost universal marriage.

Figure 1.1 The Hajnal line.

From the world hegemony of North Atlantic powers since the eighteenth century, we should expect this family system to be a global pacesetter of change, and so, it has turned out. Large-scale birth control first emerged in the aftermath of the great North Atlantic revolutions, the American and the French, spreading to the rest of Europe in the late nineteenth century and reaching the rest of the world only after World War II (WWII), into sub-Saharan Africa only in the l990s. Western European and North American women’s rights began to expand in the nineteenth century, again before anywhere else, and from a basis of historically circumscribed patriarchy. But even the theoretical principle of male–female family equality took a long time to conquer all of Western Europe, West Germany only in l976 – when privileged paternal authority was abolished – and all aspects of French family law only by l985, after a basic breakthrough in l970, when “parental authority” replaced “paternal power” (Therborn, 2004, pp. 98, 100).

In the course of the twentieth century, other aspects of the European family developed in an inverted V trajectory. The marriage rate rose dramatically, peaking after WWII, in most countries of Western Europe in 1965–1973, in the United States in the early l960s. Birthrates rose correspondingly, reaching a top in the United States in 1957, when a woman could be expected to have 3.8 children (US Bureau of the Census, 2012), and in Western Europe around l965. After that, marriage and births went downhill, with a massive rise of nonmarried cohabitation, pioneered in Scandinavia, and birthrates plummeting to far below reproduction, above all in Southern Europe. Under Communism after WWII, Eastern Europe pioneered egalitarian family legislation, together with Scandinavia, and pushed female labor force participation. Birthrates decreased.

- The Islamic West Asian/North African family. Islam, more than Christianity, is, of course, a world religion, spread across continents. But outside its historical homelands, the Islamic family institution has been importantly affected by other cultures, and subjected to other regional processes of twentieth-century change, including African, South Asian, and Southeast Asian.

While Islamic marriage is a contract, and not a sacrament, it, as well as family, gender, and generation relations generally, is extensively regulated by holy law. This l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Global Perspectives on Families

- Part II: Diversity, Inequality, and Immigration

- Part III: Family Forms and Family Influences

- Part IV: Family Processes

- Part V: Life Course Perspectives

- Part VI: Families in Context

- Index

- End User License Agreement