![]()

Chapter 1

Spatial Simulation Models: What? Why? How?

It is easy to see building and using models as a rather specialised process, but models are not mysterious or unusual things. We routinely use models in everyday life without giving them much thought, if any at all. Consider, for example, the word ‘tree’. We may not exactly have a ‘picture in our heads’ when we use the word, but we could certainly oblige if we were asked to draw a ‘tree’. The word is associated with some particular characteristics, and we all have some notion of the intended meaning when it is used. In effect, everyday language models the world, using concrete nouns, as a wide variety of categories of thing: cats, dogs, buses, trains, chairs, toothbrushes and so on. We do this because if we did not, the world would become an unfathomable mess of sensory inputs that would have to be continually and constantly untangled in order to accomplish even the most trivial tasks.

If you are reading this book, then you are already well-versed in using models in the language that you use everyday. We define scientific models as simplified representations of the world that are deliberately developed with the particular purpose of exploring aspects of the world around us. We are particularly concerned with spatial simulation models of real world systems and phenomena. Our aim in this book is to help you become as comfortable with consciously building and using such models as you are with the models you use in everyday language and life.

This aim requires us to address some basic questions about simulation models:

- What are they?

- Why do we need them and use them?

- How can (or should) we use them?

It is clearly important in a book about simulation models and modelling to address these questions at the outset, and that is the purpose of this chapter.

The views we espouse are not held by every scientist or researcher who uses models in their work. In particular, we see models as primarily exploratory or heuristic learning tools, which we can use to clarify our thinking about the world, and to prompt further questions and further exploration. This view is somewhat removed from a more traditional perspective that has tended to see models as primarily predictive tools, although there is increasing realisation of the power of models as heuristic devices. As we will explain, our view is in large measure a product of the types of system and types of problem encountered in the social and environmental sciences. Nevertheless, as should become clear, this perspective is one that has relevance to simulation models as they are used across all the sciences, and becomes especially important when scientific models are used, as increasingly they are, to inform critical decisions in the policy arena.

After dealing with these foundational issues, we briefly introduce probability distributions. Our goal is to show that highly abstract models, which make no claim to realism, may nevertheless still be useful. It is also instructive to realise that probability distributions are actually models of a specific kind. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of such models makes it easier to appreciate the role of more detailed models that take realism seriously and also the costs borne by this increased realism. Finally, we end the chapter by making a case for the more complicated dynamic, spatial simulation models that are the primary focus of this book.

1.1 What are simulation models?

You may already have noticed that we are using the word ‘model’ a great deal more than the word ‘simulation’. The reason for this will become clear shortly, but in essence it is because models are a more generic concept than simulations. We consider the specific notion of a simulation model in Section 1.1.5, but focus for now on what models are.

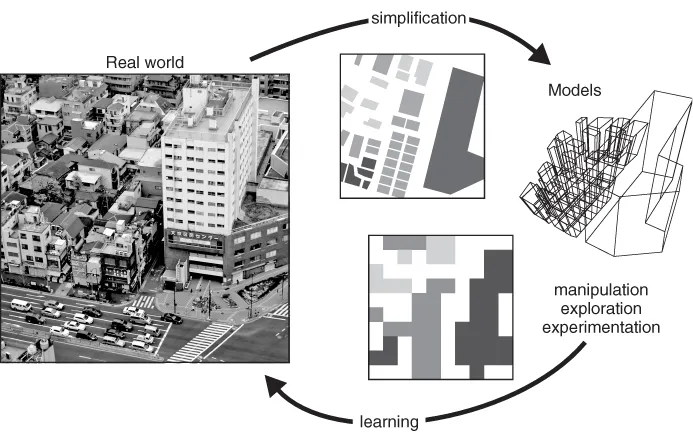

The term model is a difficult one to pin down. For many, the most familiar use of the word is probably with reference to architectural or engineering models of a new building or product design. Until relatively recently, most such models were three-dimensional representations constructed from paper, wood, clay or some other material, and they allowed the designer to explore the possibilities of a proposed new building or product before the expensive business of creating the real thing began. Such ‘design models’ are often built to scale, necessitating simplification of the full-size object so that the overall effect can be appreciated without the finer details becoming too distracting. Contemporary designers of all kinds generally build not only physical models but computer models, using computer-aided design (CAD) software to create virtual models that can be manipulated and explored interactively on screen. Design models then, are simplified representations of real objects that are used to improve our understanding of the things they represent. The underlying idea of model building of this kind is shown in Figure 1.1. An important idea is that more than one model is likely to beuseful.

Scientific models perform a similar function—and follow the same general logic of Figure 1.1. Therefore, for our purposes, we define a scientific model as

The key term in this definition is ‘simplified’. In most scientific studies there are many details of the phenomena at hand that are irrelevant from the particular perspective under consideration. When we are tackling the transport problems of a city, we focus on aspects that matter, such as the relative allocation of resources for building roads relative to those for public transport infrastructure, the connectivity of the network and how to convince more people to car-pool. We do not concern ourselves with the colours of the cars, the logos on the buses or the upholstery on the subway seats. At the level at which we are approaching the system under study some components matter and others are irrelevant and may be safely ignored. The process of model development demands that we simplify from the often bewildering complexity of the real world by deciding what matters (and what does not) in the context of the current investigation. An important consequence of this simplification process, as George Box succinctly points out, is that, ‘[m]odels, of course, are never true’ (Box, 1979, page 2). Luckily, as Box goes on to say, ‘it is only necessary that they be useful’.

1.1.1 Conceptual models

The first step in any modelling exercise is the development of a conceptual model. All scientific models are conceptual models, and a particular conceptual model can be given more concrete expression as any of the distinct types discussed below. Thus, developing a conceptual model is fundamental to the development of any scientific model. Approaching the phenomenon under study from a particular theoretical perspective will bring a variety of abstract concepts into play, and these will inform how the system is broken down into its constituent elements in systems analysis.

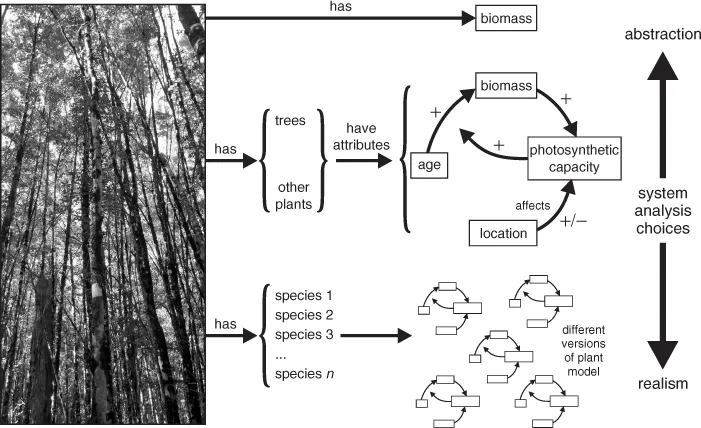

In simple cases, a conceptual model might be expressible in words (‘if parking costs more, fewer people will drive’), but usually things are more complicated and we need to consider breaking the phenomenon down into simpler elements. Systems analysis is a method by which we simplify a phenomenon of interest by systematically breaking it down into more manageable elements to develop a conceptual model (see Figure 1.2). A critical issue is the desired level of detail. In the case shown, depending on our interests, a forest might be simplified or abstracted to a single value, its total biomass. A more detailed model might break this down into the biomass stored in trees and other plant species, with a single submodel representing how both categories function, the difference between trees and other plants being represented by differences in attribute values. A still more detailed analysis might consider individual species and develop submodels for each of them. The most appropriate model representation is not predetermined and will depend on the goals of the model-building exercise. In this case, a focus on carbon budgets may mean that the high-level ‘biomass only’ model is most appropriate. On the other hand, if we are concerned about the fate of a particular plant species faced with competition from invasive weeds, then a more detailed model may be required.

In the systems analysis process, we typically break a real-world phenomenon or system down into general elements, as follows:

Components are the distinct parts or entities that make up the system. While it is easy to say that a phenomenon can be broken down into components, this step is critical and typically difficult. The components chosen will have an impact on the resulting model's behaviour so that these basic decisions are of fundamental importance to how adequate a given representation will be. An important assumption of the systems approach is that the behaviour of the components in isolation is easier to understand than that of the system as a whole.

State variables are individual component or whole-system level measures or attributes that enable us to describe the overall condition of the system at a particular point in space or moment in time. Total forest biomass might be such a variable in Figure 1.2.

Processes are the mechanisms by which the system and its components make the transition from one state to another over time. Processes dictate how the values of the involved components' state variables change over time.

Interactions between the system components. In most systems not all components interact with each other, and how component interactions are organised is an important aspect of a system's structure. In many of the systems which interest us in this book, in...